Continuing Education Activity

Bacterial prostatitis (BP) is an infection of the prostate gland occurring in a bimodal distribution in younger and older men. It can be acute (ABP) or chronic (CBP) in nature and, if not treated appropriately, can result in significant morbidity. This activity highlights the causes, pathophysiology, and presentation of acute bacterial prostatitis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of acute bacterial prostatitis.

Review the presentation of a patient with acute bacterial prostatitis.

Outline the treatment and management options available for acute bacterial prostatitis.

Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with acute bacterial prostatitis.

Introduction

Bacterial prostatitis (BP) is a bacterial infection of the prostate gland occurring in a bimodal distribution in younger and older men. It can be acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP) or chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP) in nature and, if not treated appropriately, can result in significant morbidity. As a result, the causes, pathophysiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of BP are important for providers to understand in emergency and ambulatory settings.[1][2][3]

In general, acute bacterial prostatitis is rare; when it occurs, it is often associated with bladder outlet obstruction or an immunocompromised state.

Etiology

Bacterial prostatitis (BP) is most commonly caused by infection from members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, but organisms from other families can be responsible and are more likely in certain high-risk populations. Escherichia coli is the most common isolate from urine cultures and is the causative agent in the majority (approximately 50% to 90%) of cases. Other common isolates include the species Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Pseudomonas. Gram-positive organisms such as Enterococcus species and Staphylococcus species and sexually transmitted organisms such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum are also sometimes implicated. Prostate manipulation from procedures such as transrectal prostate biopsy, transurethral prostate biopsy, cystoscopy, and catheterization appears to increase the risk of pseudomonas, mixed organisms, staphylococcal infections, and treatment failure prostatitis.

Special consideration should be given to immunocompromised patients as they are at higher risk of contracting BP from atypical organisms such as Salmonella species, Mycobacterium species, Staphylococcus species, among others. Though this article focuses on bacterial etiologies, fungal and viral etiologies should be strongly considered in these patient populations as well. Despite the fact that Enterobacteriaceae are the most common causative organisms in both ABP and CBP, gram-positive organisms and atypicals are more likely in CBP than in ABP; although, the role of gram-positive organisms in CBP is debated despite the fact they sometimes are isolated in culture.[4][5]

Risk factors include:

- Phimosis

- Intraprostatic ductal reflux

- Unprotected vaginal/anal intercourse

- Development of a urinary tract infection

- Indwelling catheter

- Transurethral biopsy/surgery

- Congenital abnormality of the ureter

- Sexual abuse

Epidemiology

Prostatitis has a bimodal distribution in young to middle-aged men and in older men and has a prevalence of approximately 8% to 16%; however, it should be noted that only 5% to 10% cases of prostatitis are identified as bacterial in origin. As a result, the NIH has created four classifications for prostatitis: ABP, CBP, chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome, and asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis. Bacterial prostatitis is relatively uncommon when compared to other causes of prostatitis. Men who have one episode of bacterial prostatitis are more likely to have subsequent episodes and progress to chronic bacterial and nonbacterial prostatitis. Risk factors for bacterial prostatitis include prostate manipulation, urethral stricture, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), phimosis, urethritis, diabetes, and other immune-compromising states, and a history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), among others. Prostatitis also appears to increase the risk of developing BPH and possibly prostate cancer.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

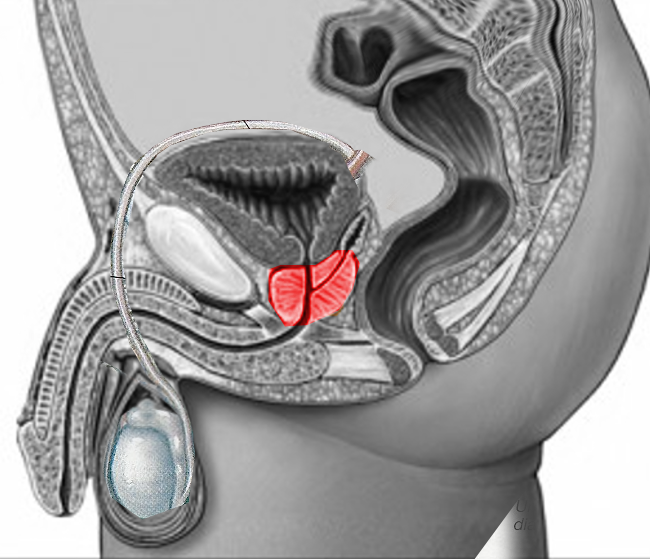

The proposed mechanisms of BP all involve the infiltration of pathogenic organisms that are capable of overcoming the prostate gland's natural immune defenses. Most commonly, BP is secondary to ascending infection from urethritis, cystitis, and epididymal-bronchitis, but BP is also often caused by direct inoculation from prostate biopsy or manipulation. Less commonly, BP can be caused by hematogenous or lymphatic seeding from sepsis or other sources of infection in the body. The pathophysiology of CBP is less well understood but may involve the development of bacterial biofilms.[3]

In young men, the most common pathology includes an ascending urethral infection following anal or vaginal intercourse. In the elderly, prolonged catheterization and instrumentation are two common causes.

History and Physical

ABP typically presents with abrupt signs and symptoms of infection, while CBP often presents more subtly. Patients with ABP typically complain of fever, malaise, myalgias, dysuria, urinary frequency/hesitancy, and pelvic pain. On physical exam, the prostate is often enlarged and exquisitely tender to palpation. Vigorous manipulation of the prostate gland should not be performed in ABP as this may acutely exacerbate the patient's condition. The patient should also be evaluated for signs and symptoms of urinary retention, which may present with suprapubic tenderness and suprapubic fullness. Patients suspected of having ABP should also be assessed for CVA tenderness, as pyelonephritis is an important differential.

The symptoms of CBP are, by definition, chronic and recurring and are often less severe than acute prostatitis but can nevertheless significantly impact the quality of life. As with ABP, CBP can present with signs and symptoms of urinary tract infection, urinary retention, and pelvic pain; however, men with CBP do not typically appear acutely ill, and some men simply have chronic asymptomatic bacteriuria. The prostate is not acutely inflamed on the exam but may be tender to palpation. Men with CBP may also present with sexual dysfunction.

Evaluation

The evaluation of acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP) depends largely on individual patient characteristics and suspicion for ABP complications, while the evaluation of CBP is most appropriately performed by a urologist or in close consultation with a urologist. At a minimum, once ABP is suspected based on history and physical examination, the patient should be evaluated with midstream urinalysis and urine culture. If the patient meets sepsis criteria or has significant medical comorbidities, blood cultures, lactic acid, metabolic panel, and complete blood count should be obtained.

While imaging is not required in all cases, it should be strongly considered in the form of CT or TRUS to evaluate for a prostatic abscess in patients who are immunocompromised or predisposed to bacteremia or embolic bacterial seeding. It should also be strongly considered in patients who are clinically worsening despite appropriate treatment. Urology should be consulted for possible suprapubic catheterization when patients present with acute urinary retention in the setting of ABP, as the passage of a transurethral urinary catheter may worsen the patient's condition. PSA and inflammatory markers such as CRP and ESR are of limited utility in ABP due to a lack of specificity. If STI is suspected or if the urethral discharge is present, N. gonorrhea and C. trachomatis testing should be performed. Diagnosis of chronic prostatitis is best performed by a specialist utilizing either the Meares and Stamey four-glass test or the simpler two-glass pre-massage and post-massage test and possibly semen sample with culture and urodynamic studies.

The four-glass test, as its name implies, is a test of four different samples: initially voided urine, mid-stream urine, expressed prostatic secretions, and post-prostate massage urine. The 2-glass test is performed by obtaining pre-massage and post-prostate massage urine samples. The 4-glass test is not performed often as it is difficult to carry out for the patient and the provider and has poor supporting evidence.[8][9]

A prostate biopsy is contraindicated in the presence of an acute infection because of potential seeding to adjacent organs. In addition, the biopsy can be excruciatingly painful.

Treatment / Management

Management of acute bacterial prostatitis (ABP) involves both choosing appropriate spectrum antibiotics that have good prostate tissue penetration and managing the complications and sequelae of the disease. The prostate does have some unique structural and biochemical characteristics that render certain antibiotics less effective. The prostate gland tends to be alkaline, and its capillaries are not as permeable as many other tissue capillaries. Therefore, antibiotics with high pKa and good fat solubility achieve higher tissue concentrations. Fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, macrolides, and trimethoprim (but not sulfamethoxazole) generally have these characteristics. However, acutely inflamed prostate tissue is penetrated by most antibiotics (except nitrofurantoin), which gives the clinician several options in treating ABP.

Treatment of CBP should be guided by culture results and should be done with antibiotics that achieve therapeutic prostate concentrates, as initiating antibiotic treatment emergently is not warranted and can wait on culture results. CPB treatment is two to six weeks in duration. As mentioned above, Enterobacteriaceae organisms are the most common cause of BP, so empiric treatment in ABP should aim to cover these organisms. Patients with ABP who are not severely ill and have none of those above risk factors for treatment failure from antibiotic resistance and/or atypical organisms can be discharged on oral fluoroquinolones or Bactrim for 2 to 4 weeks with follow-up culture to ensure resolution. Patients who are suspected of a sexually transmitted cause of prostatitis should be treated with a single dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone followed by two weeks of doxycycline. Patients who meet sepsis criteria, have urinary retention, or have risk factors for treatment failure and/or resistant organisms should be admitted to the hospital and started on parenteral antibiotics.

Initial choices may include a fluoroquinolone plus an aminoglycoside or antipseudomonal penicillin or cephalosporin. As mentioned earlier, imaging should be strongly considered with TRUS or CT in patients who have failed treatment or who are at risk for bacterial seeding to evaluate for prostatic abscess, which may require surgical drainage.

Urology should be consulted for urinary retention in the setting of ABP for possible suprapubic catheter placement. Patients who are admitted for ABP should ultimately be discharged on oral antibiotics selected based on culture results and with those above favorable biochemical properties.[10][11][12]

Some patients may benefit from the use of an alpha-blocker as it may lower the outflow obstruction. Terazosin is often the drug of choice, but treatment is often required for months. If an abscess has developed, this usually requires surgical drainage. This may be done either through perineal or transrectal aspiration in patients who fail to improve with antibiotic therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of bacterial acute prostatitis include:

- Urethritis

- Prostate cancer

- Urinary tract infection

Prognosis

Patients who respond to antibiotics do have a favorable prognosis, but those who fail to respond usually end up with a surgical procedure for an abscess. Massive inoculation of the prostate with bacteria has also been associated with infertility. A prostatic abscess is rare but may occur in patients with indwelling catheters. Other complications include progression to chronic prostatitis, epididymitis, or pyelonephritis. At least 10% may develop chronic pelvic pain.

Complications

The complications include:

- Sepsis

- Epididymitis

- Abscess

- Chronic prostatitis

- Chronic pelvic pain

Pearls and Other Issues

A small, albeit significant proportion (approximately 5% to 10%) of patients with ABP will progress to CBP. Several risk factors for progression to CBP have been identified and include alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, large prostate volume, and history of prostate manipulation. Protective factors against progression to CPB appear to include cystostomy in ABP and prolonged antibiotic therapy in ABP. Though more research is needed on this topic, it does appear that risk factor modification may help prevent the progression of ABP to CBP.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acute bacterial prostatitis is associated with an enormous burden on healthcare costs. While physicians manage the acute infection, the key is to prevent the condition in the first place. Nurses should be aware that unnecessary urethral catheterization should be avoided. The nurse should also educate the patient on barrier protection if participating in anal sex. In addition, the pharmacist should remind patients that administering prophylactic antibiotics before a transrectal biopsy can lower the risk of a urinary tract infection and bacteriuria. The pharmacist should also follow up on the culture to ensure that the right type of antibiotic is being used. In addition, patient compliance with antibiotics is vital for success. The nurse should also educate the patient on adequate hydration and the use of antipyretics. If the patient develops urinary retention, he should seek immediate medical assistance. Close communication between the team members and the urologist is essential to lower morbidity and improve outcomes.[13][14] (Level V)

Outcomes

Patients who respond to antibiotics have a good outcome. However, those who do not seek treatment or do not respond to antibiotics may have lower rates of fertility. Other studies have reported that patients with heavy bacterial inoculation also tend to have impaired sperm motility and viability. Abscess formation is a rare complication of acute bacterial prostatitis and is known to occur in patients with diabetics, those who are immunocompromised, and those who have undergone urethral instrumentation or have prolonged indwelling urinary catheters. Rare reports exist of pyelonephritis, chronic prostatitis, and sepsis. At least 10% of patients with acute bacterial prostatitis will develop chronic pelvic pain syndrome.[5][15] (Level V)