Continuing Education Activity

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder of unknown etiology characterized by noncaseating granulomas in organs. This condition mostly affects young adults and characteristically presents with reticular opacities in the lungs and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Other involved sites include eyes, skin, joints, and in some cases, the reticuloendothelial system, musculoskeletal system, exocrine glands, heart, kidney, and central nervous system. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of sarcoidosis and explains the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the characteristic signs and symptoms of sarcoidosis.

Explain how to diagnose sarcoidosis.

Describe the appropriate monitoring for asymptomatic, non-progressive sarcoidosis.

Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to monitor symptoms and progression of the asymptomatic disease, which will improve outcomes for patients with sarcoidosis.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder of unknown etiology that mostly affects young adults worldwide and presents with noncaseating granulomas in various organs. Characteristically, it presents with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and reticular opacities in the lungs. Other major involved sites include skin, eyes, and joints. However, it can be expressed to a variable degree in the musculoskeletal system, reticuloendothelial system, exocrine glands, heart, kidney, and central nervous system.[1][2][3]

Etiology

It is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that manifests as noncaseating granulomas in multiple systems. Various associations have been described, including occupational and environmental exposures to beryllium, dust, and other agents causing asthma. Various microorganisms like mycobacteria and propionibacteria have been associated. Possible infective etiology has been described in a few studies where sarcoidosis developed in a previously negative individual after cardiac or bone marrow transplantation.[4][5]

Genetic components and disease in more than one family member are usually related to antigens of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), especially DR alleles. Few studies have described other less common genomes and angiotensin-converting enzyme genotypes in a few patients.

Cytokines, including Th1, IL-2, IL6, IL 8, IL12, IL 18, IL 27, and interferon (IFN) gamma and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha are closely associated with sarcoidosis. Few of these are implicated in granuloma formation with macrophage and epithelioid accumulation, activation, and aggregation. Some of these interleukins are believed to act as disease modifiers.

Epidemiology

The incidence is 11 cases per 100,000 in whites but 34 cases per 100,000 in African Americans, with a lifetime risk of 2.4 percent in the United States. Extrapulmonary sarcoid is seen in up to 25 to 30 percent of patients. Cardiac involvement is seen more commonly in males, while skin and eye features are more prominent in women. Extrapulmonary features can differ in age of presentation, gender, and ethnicity.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Pathogenesis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is poorly understood and attributable to both genetic and environmental factors. A key role in the development of sarcoidosis is played by T cells as they promote cellular immune reaction and are usually associated with an inverted CD4/CD8 ratio. It is well characterized by noncaseating granuloma, typically containing macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and epithelioid cells, in addition to lymphocytes, monocytes, mast cells, and fibroblasts. There is a role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and TNF receptors, as both are increased in this disease. This has been evidenced by the role of anti-TNF agents, such as pentoxifylline and infliximab. In addition to the T cell's role, B cell hyperreactivity with immunoglobulin production is also implicated. Active sarcoidosis has also been associated with plasmatic hypergammaglobulinemia. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels correlated with elevated soluble HLA class I antigens levels in serum.[8]

Histopathology

Biopsy of lymph nodes will reveal non-caseating granulomas.

History and Physical

Symptoms are variable; typically, patients present with a persistent dry cough, fatigue, and shortness of breath. Other symptoms include painful red lumps on the skin, uveitis with the blurring of vision, hoarseness of voice, palpable lymph nodes at multiple sites including the axilla and neck, painful swollen joints, hearing loss, seizures, or psychiatric disorders could be observed as part of neurological manifestations. Cardiomyopathy, conduction defects, renal calculi, and enlarged liver are observed in a few cases.

A wide range of cutaneous manifestations can be classified as papular, maculopapular, nodular, subcutaneous, hypopigmented, and plaque sarcoidosis. The most common lesions in cutaneous sarcoidosis are papular sarcoidosis involving the upper half of the face, the back of the neck, and previous trauma, scar sites, and tattoos. Lupus pernio is a variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis that presents with violaceous or erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules, mainly involving the central facial skin. Other well-described skin manifestations of sarcoidosis include nodular sarcoidosis. Plaque-like lesions and subcutaneous non-tender nodules are also commonly seen.

Erythema nodosum (EN) is seen in a variety of other conditions, including sarcoidosis, and usually presents with painful nodules on shins. It is characterized as panniculitis and is a part of Löfgren syndrome. Skin lesions can appear up to 10 or more years after the initial injury or tattoo.

Ocular manifestations are seen in close to 50% of patients, of which the most common clinical feature is uveitis. The CD4/CD8 ratio of vitreous lymphocytes has prognostic value.

Heart block and sudden death have also been reported in sarcoidosis. Prophylactic insertion of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is recommended in patients who develop cardiac sarcoidosis.

CNS manifestations include diabetes insipidus followed by hyperprolactinemia.

The quality of life of symptomatic patients is poor. Many develop psychiatric symptoms, including depression and anxiety.

Evaluation

Lab Tests

- Complete blood count and differential looking for anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, liver function tests, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, electrolytes, and serum calcium looking for hypercalcemia. ESR and C-reactive protein are nonspecific tests, often elevated.

- Elevated serum alkaline phosphatase concentration suggests diffuse granulomatous hepatic involvement.

- Serologic tests can be considered, including serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), adenosine deaminase, serum amyloid A, and soluble interleukin-2 receptor.

- Kveim test is similar to tuberculin skin test and evokes a sarcoid granulomatous response. It is of limited significance.

Radiographic Tests

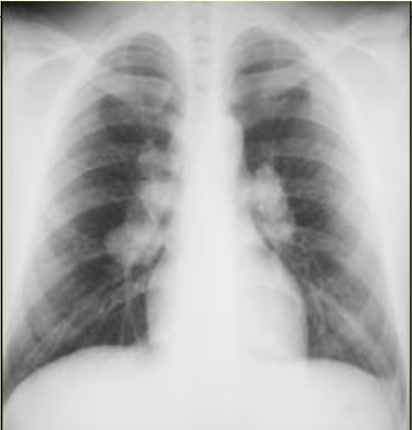

- Lungs are the main site of involvement; imaging tests include chest radiograph, CT of the chest, fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), gallium-67, thallium-201, technetium sestamibi (MIBI-Tc), and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

- Cardiac or CNS-affected sarcoidosis is better diagnosed with the help of an MRI or PET scan.

- Pulmonary function tests may reveal a decrease in DLCO, and a restrictive pattern is seen in advanced cases. About 10% of patients will have an obstructive pattern. Patients with DLCO less than 60% predicted, combined with oxygen saturation of less than 90 on the walk test, need to be evaluated for pulmonary hypertension.

Radiographic Stages

- Stage I: Presence of bilateral hilar adenopathy

- Stage II: Bilateral hilar adenopathy and reticular opacities

- Stage III: Reticular opacities with shrinking hilar nodes (mainly infiltrates)

- Stage IV: Reticular opacities with fibrosis

In the case of a clear chest X-ray in a patient with unexplained dyspnea or cough, (HRCT) of the chest should be considered.

Histopathology

Sarcoidosis characteristically has noncaseating granulomas with aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes, giant cells, and mature macrophages.

To rule out systemic disease, pulmonary function testing, electrocardiogram, echocardiography, urinalysis, and tuberculin skin testing should be considered.

Follow-up of the pulmonary disease can be done with pulmonary function tests and a carbon monoxide diffusion capacity test of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO).[9][10][11]

A biopsy is often required to confirm the diagnosis. Transbronchial biopsy has a high yield. If that fails, then a mediastinoscopy to perform a lymph node biopsy is required. The key feature is noncaseating granulomas in the absence of mycobacteria and fungi.

Treatment / Management

Pulmonary sarcoidosis is often an asymptomatic, non-progressive disease and requires no treatment, as a majority of patients undergo spontaneous remission. Close monitoring of symptoms, chest radiograph, and pulmonary function is continued at three to six-month intervals should be considered in asymptomatic patients. For patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis causing worsening symptoms, stage II to III radiographic findings should be considered for oral glucocorticoids at 0.3 to 0.6 mg/kg for 4 to 6 weeks. If there is no improvement in symptoms, radiographic abnormalities, and pulmonary function tests, steroids may be continued for an additional four to six weeks. Maintainance steroids are not needed; steroid tapering to a dose of 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg (usually 10 to 20 mg) per day should be considered over at least six to eight months. Methotrexate, azathioprine, infliximab, leflunomide, and antimalarial agents may be considered as steroid-sparing agents in patients who are unable to tolerate steroids.[12][13]

Lung transplant is an option for patients with end-stage lung disease. However, the transplant is also associated with risks and the need to take immunosuppressive therapy for life.

Differential Diagnosis

- Tuberculosis

- Cat scratch disease

- Lung cancer

- Lymphoma

- Occupational lung disease

- Fungal infection

Prognosis

Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment and often remain stable for many years. However, those who develop symptomatic lung or extrapulmonary disease tend to have a guarded prognosis. Relapse of symptoms is common, and many patients with advanced disease develop dyspnea and pulmonary hypertension. The overall mortality rate for untreated patients is about 5%. However, prolonged treatment with corticosteroids is not benign, and the adverse effects of these drugs are common.

Complications

- Pulmonary hypertension

- End-stage lung disease

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Sarcoidosis has no obvious cause, and hence prevention is not possible. The disorder also resolves spontaneously; hence, treatment is not always required. However, severe cases do need follow-up. The management of patients with sarcoidosis is best done in an interprofessional fashion with a team of healthcare workers that includes a cardiologist, neurologist, radiologist, pulmonologist, cardiac nurse, respiratory therapist, and pharmacist. The patient needs regular chest X-rays since it is a marker for disease progression. Some patients may benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation and the use of bronchodilators. If the disease is advanced, a regular eye exam is important.

Symptomatic patients need drug therapy, and the pharmacist needs to emphasize the importance of compliance and the need to follow up since most drugs have adverse side effects. Patients who fail to respond to steroids may need potent biological agents. In addition, patients with end-stage lung disease may need to be seen by a transplant nurse to determine their eligibility. Further, patients with eye symptoms should be referred to an ophthalmologist.

At each clinic visit, the nurse should ensure that the patient gets a regular 12-lead ECG because the heart block is not uncommon. The pharmacist and nurse should educate the patient on the importance of discontinuing smoking and abstaining from alcohol. Finally, patients who are managed with steroids should be educated by all members of the team about the side effects of the drugs used. Only through such an interprofessional team approach can the outcomes of sarcoidosis be improved.[14][15] [Level 5]

Outcomes

In many patients with sarcoidosis, no treatment is required, and the disorder spontaneously resolves. However, the disease may take a fulminant course with severe symptoms in a certain number of people. Factors that indicate a poor prognosis include significant chest imaging findings, extrapulmonary involvement, and the presence of pulmonary hypertension. Many studies indicate that a chest X-ray is an excellent marker for disease prognosis. In severe cases, patients may require oxygen and experience heart block and respiratory failure. Data regarding mortality are not available because, in many cases, long-term follow-up is missing. Overall, it appears that about one-fifth of patients develop functional impairment, and there is a mortality rate of 3% to 5% in patients who are not treated. The highest mortality rates are in African American females past the fifth decade of life.[16][17] [Level 5]