Continuing Education Activity

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare, chronic, and idiopathic granulomatous disease of collagen degeneration. It has an associated risk of ulceration and is classically associated with diabetes mellitus, usually type 1. There is a thickening of the walls of the blood vessels and deposition of fat. The major complication of the disease is the formation of an ulcer, mainly occurring after trauma. Uncommonly, infections can also occur. Moreover, if necrobiosis lipoidica becomes chronic, it may rarely turn into squamous cell carcinoma. The cause of necrobiosis lipoidica remains unknown. However, vascular disturbance involving immune complex deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degeneration has been the most common theory. This activity reviews the pathophysiology of necrobiosis lipoidica and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in ensuring the best patient outcomes.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of necrobiosis lipoidica.

- Review the presentation of necrobiosis lipoidica.

- Summarize the treatment of necrobiosis lipoidica.

- Outline the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by necrobiosis lipoidica.

Introduction

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a rare, chronic, and idiopathic granulomatous disease of collagen degeneration. It has an associated risk of ulceration and is classically associated with diabetes mellitus, usually type 1. There is a thickening of the blood vessels' walls and fat deposition. The major complication of the disease is the formation of an ulcer, mainly occurring after trauma. Uncommonly, infections can also occur. Moreover, if necrobiosis lipoidica becomes chronic, it may rarely turn into squamous cell carcinoma.[1][2][3]

Necrobiosis lipoidica was first mentioned as dermatitis atrophicans lipoidica diabetica in 1929 by Oppenheim. However, in 1932, Urbach renamed the disease necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum (NLD).

In 1935, the first case was reported by Goldsmith in a nondiabetic patient. Subsequently, more cases of NLD were described by Meischer and Leder in nondiabetic patients in 1948. In 1960, Rollins and Winkelmann also published about NLD in nondiabetic patients. Hence, the suggestion to exclude diabetes from the name of the disease was put forward.[4] Today, a broader term, necrobiosis lipoidica, encompasses all patients with the same clinical lesions without considering the presence or absence of diabetes.

Etiology

The cause of necrobiosis lipoidica remains unknown. However, the most common theory is vascular disturbance involving immune complex deposition or microangiopathic changes leading to collagen degeneration.[5] Following are some theories that have been proposed over time about the etiology of the disease:

Diabetic Microangiopathy

As there exists a strong association between diabetes and necrobiosis lipoidica, several studies have emphasized diabetic microangiopathy to be the prime etiological factor.[6] This can be further supported by the fact that the effects of diabetes on the ocular and renal vasculature are comparable to the vascular changes observed in necrobiosis lipoidica. In addition, glycoprotein deposition has often been described in blood vessel walls in cases of diabetic microangiopathy. Similarly, a glycoprotein deposition is observed in necrobiosis lipoidica.

Immunoglobulins, Complement, and Fibrinogen

It has been described that the deposition of immunoglobulins, C3 - the 3rd component of complement, and fibrinogen in the walls of the vasculature results in the development of necrobiosis lipoidica.[7] Some argue that an antibody-mediated reaction may start the blood vessel changes causing necrobiosis in necrobiosis lipoidica.

Abnormal Collagen

Additionally, it has been theorized that the etiology of necrobiosis lipoidica is associated with abnormal collagen. It is well-recognized that abnormal collagen fibrils are responsible for diabetes-related end-organ damage and expedited aging. In diabetes, collagen cross-linking increases as a result of elevated lysyl oxidase levels. This increase in collagen cross-linking could cause the thickening of the basement membrane in necrobiosis lipoidica.

Impaired Neutrophil Migration

It also has been observed that there could be defective neutrophil migration causing an increase in the number of macrophages, possibly justifying the formation of granuloma in necrobiosis lipoidica.[8]

Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)–Alpha

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha has been observed to play a potentially crucial role in granulomatous diseases such as necrobiosis lipoidica and disseminated granuloma.[9] It is raised in the sera and skin of the patients suffering from these conditions.

A study conducted by Hammer et al. on 64,133 patients who have type 1 diabetes observed that those with necrobiosis lipoidica were more likely to have worse metabolic control, a lengthier course of diabetes, and an increased need for insulin doses as opposed to the other patients. Additionally, a correlation was noted between celiac disease and necrobiosis lipoidica, and it was observed that a larger percentage of patients having necrobiosis lipoidica had raised levels of thyroid antibodies.[7]

Epidemiology

Necrobiosis lipoidica has an increased prevalence in individuals with diabetes, although this association is currently challengable. The incidence among people with diabetes is only 0.3% to 1.2%. Necrobiosis lipoidica precedes diabetes in up to 14% and appears simultaneously in up to 24%, and occurs after diabetes is diagnosed in 62% of cases. There is no proven connection between the level of glycemic control and the likelihood of developing necrobiosis lipoidica.

Although it may present in healthy individuals with no underlying disease, other commonly associated conditions are thyroid disorders and inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis. In one series, researchers found surprisingly lower rates of arterial hypertension than in the standard population, while obesity and fatty acid disorders were at a standard rate. No evidence for the induction of necrobiosis lipoidica by infection or underlying malignancies was found among those patients.

There appears to be a predominance of 77% in females.[10] Also, the onset in women is younger than in men. Necrobiosis lipoidica has an average age of onset between 30 and 40 years.

A study by Hashemi et al. observed that in patients having necrobiosis lipoidica, those with diabetes had a median age of 45 years as opposed to 52 years in patients who were not suffering from diabetes.[11]

Erfurt-Berge et al. carried out a retrospective study on 100 patients having necrobiosis lipoidica and found that female sex and middle age were characteristic in patients with the condition. The investigators also published that ulceration, which was seen in 33% of patients, was most prevalent in men and in patients suffering from diabetes mellitus, and thyroid problems occurred in 15% of all patients.[12]

Pathophysiology

An immunologically mediated vascular disease has been suggested as the primary cause of the altered collagen. The most common vascular abnormalities seen in necrobiosis lipoidica lesions are thickening of the vessel walls, fibrosis, and endothelial proliferation leading to occlusion in the deeper dermis, especially in patients with diabetes. Deposition of fibrin, IgM, and C3 at the dermo-epidermal junction of blood vessels has been shown in immunofluorescence studies.[13]

The concentration of collagen decreases in necrobiosis lipoidica, and electron microscopy shows a loss of the cross-striations of collagen fibrils and an important variation in the diameter of individual fibrils. Fibroblasts cultured from necrobiosis lipoidica synthesize less collagen than their counterparts from the unaffected skin.[14]

Granuloma formation has been thought to occur as a result of defective neutrophil migration allowing macrophages to take on the neutrophil role and accumulate with subsequent granuloma formation.

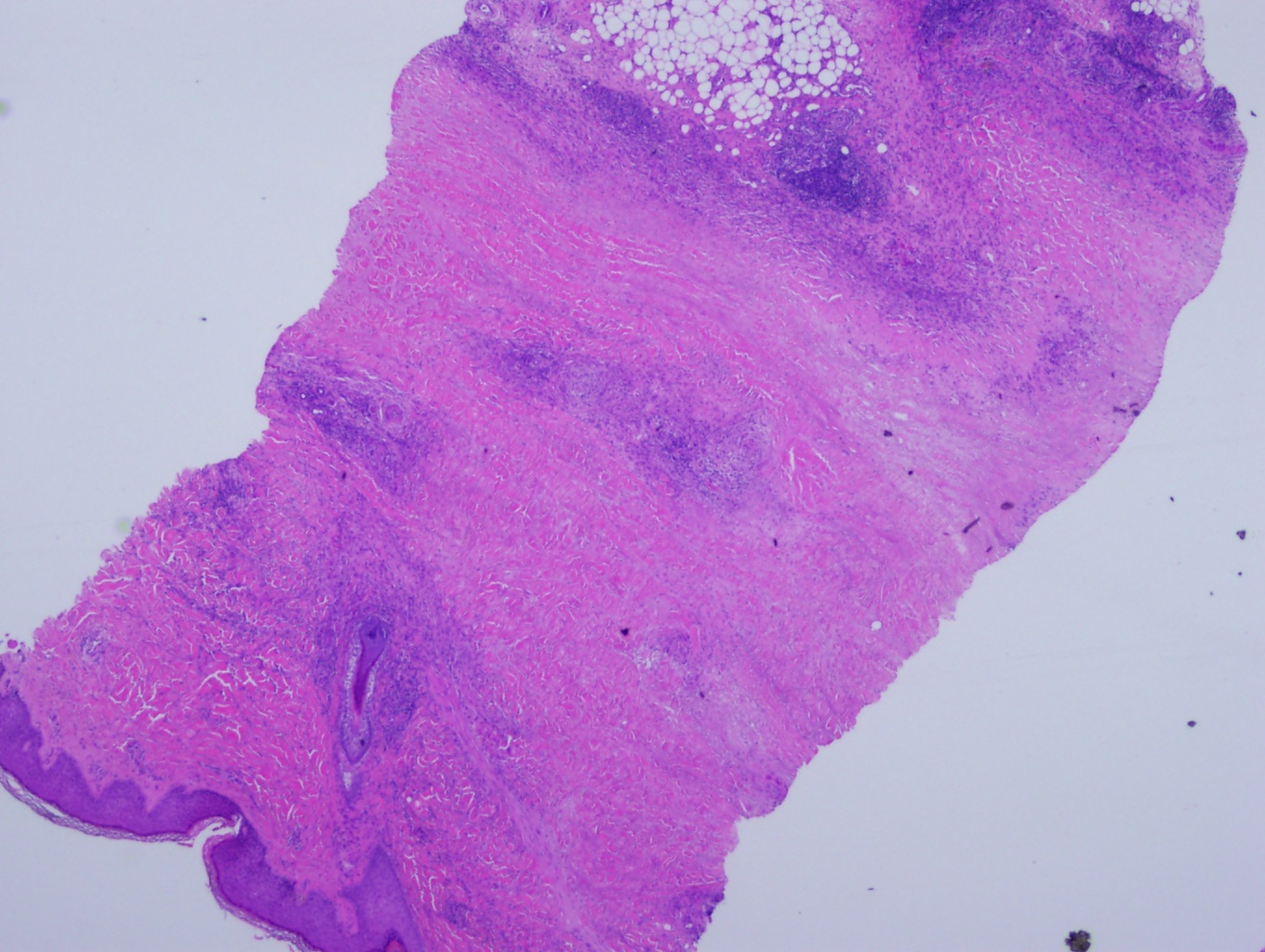

Histopathology

Histopathologically biopsy specimens from the palpable inflammatory border reveal scattered palisaded and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with layered tiers of granulomatous inflammation parallel to the skin surface involving the entire dermis and extending into the subcutaneous fat septae. The epidermis is normal or atrophic. Focal loss of elastic tissue can be demonstrated in areas of connective tissue sclerosis. There is no significant mucin deposition in the center of the palisading granulomas, in contrast with granuloma annulare.

Necrobiosis lipoidica demonstrates interstitial and palisaded granuloma formation, including subcutaneous layers and dermis. The granulomas are organized in a layered manner and are admixed with patches of collagen degeneration. The granulomas are comprised of histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. A decrease in the number of dermal nerves is another feature of necrobiosis lipoidica.

The prime findings on histopathology are endothelial cell swelling and thickening of the blood vessel walls from the middle to deep dermis, also a characteristic of diabetic microangiopathy.

Direct immunofluorescence microscopy shows IgM, IgA, fibrinogen, and C3 in the blood vessels causing vascular thickening.[15]

A study by Ramadan et al. observed that cutaneous sarcoidosis could be differentiated from necrobiotic granulomas with the help of dermoscopy. They found that cutaneous sarcoidosis varies dermoscopically from necrobiotic granulomas due to the presence of a pink homogenous background, white scarlike depigmentation, translucent orange regions, and fine white scales.[16]

History and Physical

Necrobiosis lipoidica is characterized by yellow-brown, atrophic, telangiectatic plaques with an elevated violaceous rim, typically present in the pretibial surface. Less typical anatomic locations include the upper extremities, face, and scalp, where lesions may be more straight or wavy and are less weakened.

Lesions usually begin as small, firm, red-brown papules that gradually enlarge and then develop central epidermal atrophy. Ulceration occurs in approximately a third of lesions, usually following minor trauma. The plaques are usually multiple and bilateral. These lesions can Koebnerize if they are traumatized.[17] Therefore, surgical treatments represent a challenge.

Skin lesions in classic necrobiosis lipoidica start as 1 to 3 mm, well-demarcated papules that expand to become plaques with more-indurated borders and waxy centers. In the beginning, these plaques are red to brown but progress to become more yellow, shiny, and atrophic. (As shown in the image)

The disease course appears more severe in men as they have a higher likelihood of ulceration in their lesions, reported in 58% of males vs. 15% of females. Decreased sensation to pinprick and fine touch, hypohidrosis, and partial alopecia can be found within NL plaques. Rare reports show squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of NL.

Some patients may report reduced sensation or sweat over these lesions.

Evaluation

Although the diagnosis often is based on clinical examination, a biopsy should be performed to differentiate necrobiosis lipoidica from conditions with similar clinical appearances, including granuloma annulare and necrobiotic xanthogranuloma.

If there is a concern for venous disease or peripheral arterial disease, further studies should be considered. Baseline blood work should include fasting blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin to screen for diabetes or assess glycemic control in patients known to have diabetes. If these are not diagnostic, they should be repeated on a yearly basis, as necrobiosis lipoidica can be the first presentation of diabetes.

Dermoscopy reveals yellow structureless background, white linear streaks, and linear vessels with uniform branching.

The differential diagnosis includes mainly granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, sarcoidosis, diabetic dermopathy, and lipodermatosclerosis. Lesions of granuloma annulare and sarcoidosis generally do not exhibit the same degree of atrophy, telangiectasias, or yellow-brown color. Additionally, the appearance of lipids and decreased amount of mucin in necrobiosis lipoidica helps to differentiate from granuloma annulare.[18]

Treatment / Management

No treatment has proven to be effective in necrobiosis lipoidica. In patients with diabetes mellitus, control of blood glucose usually does not significantly affect the course. In the absence of ulceration or symptoms, it is reasonable not to treat necrobiosis lipoidica, given that up to 17% of lesions may resolve spontaneously. Compression therapy controls edema and promotes healing in patients with associated venous disease or lymphedema.[19][11][20]

When ulcerations are present, proper wound care principles are essential. First-line therapy includes potent topical corticosteroids for early lesions and intralesional corticosteroids injected into the active borders of established lesions. For inactive, atrophic lesions, topical steroids should be avoided as they may exacerbate the atrophy and increase the risk of new ulcerations.

Ultraviolet (UV) light therapy is used for various inflammatory dermatoses. Psoralen and ultraviolet light A (PUVA) decreases the actively inflamed borders but has no clinical effects on atrophic scars.

Calcineurin inhibitors inhibit T-cell activation by blocking calcineurin resulting in both anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Topical tacrolimus has been shown to be effective in resolving ulceration associated with necrobiosis lipoidica.[21][22][23]

TNF is an important regulator of the formation of granulomas. The monoclonal antibodies adalimumab and infliximab bind directly to soluble TNF-alpha to prevent its action. Etanercept is a fusion protein made up of the Fc portion of human IgG1 and TNF receptors that also inhibit TNF function. Both etanercept and infliximab have been repeatedly found to be effective as monotherapy for ulcerating necrobiosis lipoidica.

A study by Erfurt-Berge et al. found that topical steroids were predominantly used. Calcineurin inhibitors and phototherapy were the next most frequently used treatments. Systemically, fumarate esters were commonly employed, followed by steroids and dapsone.[24]

Antiplatelet aggregation therapy with dipyridamole and aspirin has been tried based on the theory that necrobiosis lipoidica is due to platelet-mediated vascular occlusion or altered platelet survival.[25] The results of double-blind studies have been variable, but overall, some beneficial effects have been observed from the therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of necrobiosis lipoidica is distinct, but there are still many atypical appearances, and early presentations can be hard to recognize.[26] The following are some important considerations:

- Acute complications of sarcoidosis

Prognosis

As the management of necrobiosis lipoidica is not very reassuring, its prognosis is also not very satisfactory. The disease is classically chronic, having variable progression. Squamous cell cancers can be found in more chronic lesions of necrobiosis lipoidica associated with previous trauma and ulceration.[1]

From an aesthetic viewpoint, the prognosis of necrobiosis lipoidica is not reassuring. Treatment can help halt the expansion of lesions that tend to have a chronic course. Lesional ulcerations can result in significant morbidity, requiring comprehensive wound care. These ulcers can be painful. They may become infected or heal with scarring.

Complications

Following are some complications of necrobiosis lipoidica:

- Long-term scarring

- Infection

- Sepsis

- Squamous cell cancer

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients suffering from diseases associated with necrobiosis lipoidica should be made aware of the clinical presentation of necrobiosis lipoidica so that as soon as the lesions begin, they may contact their primary care providers. This early presentation will help ensure a better prognosis.

Patients should also be made aware of the drug treatments available and their possible adverse effects.

Once they have an ulcer, they should be made knowledgeable about proper wound care in the community by the community wound nurses.

Ulcerative skin lesions may complicate the course of the disease, especially in patients with diabetes, but also in patients with arterial hypertension and/or those who are overweight. There is no data to support any preventive measure for necrobiosis lipoidica.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare skin complication of type 1 diabetes. However, its diagnosis and management are exceedingly complex. The skin lesions are best managed with an interprofessional team that includes a dermatologist, endocrinologist, wound care nurse, internist, and infectious disease specialist. There is no specific treatment for NL. The key is to ensure that diabetes is well controlled. Open wounds and ulcers need to be managed by a wound care nurse. Many newer biological agents have been used to treat skin disorders, but without clinical trials, it is difficult to know the effectiveness of these agents. These patients need long-term follow-up as the wound closure can take months. Some people may benefit from compression therapy and stockings.[27]

All interprofessional healthcare team members must contribute from their area of expertise and maintain open communication channels with the rest of the team, particularly if the patient's condition deteriorates. Open communication also includes keeping accurate and updated patient records so that everyone involved in the case can access the same up-to-date patient data. With coordinated effort, cohesive action, and good interprofessional communication, these challenging cases will have their best chances for positive outcomes. [Level 5]