Introduction

The heart is a muscular organ situated in the center of the chest behind the sternum. It consists of four chambers: the two upper chambers are called the right and left atria, and the two lower chambers are called the right and left ventricles. The right atrium and ventricle together are often called the right heart, and the left atrium and left ventricle together functionally form the left heart.[1][2][3][4]

Structure and Function

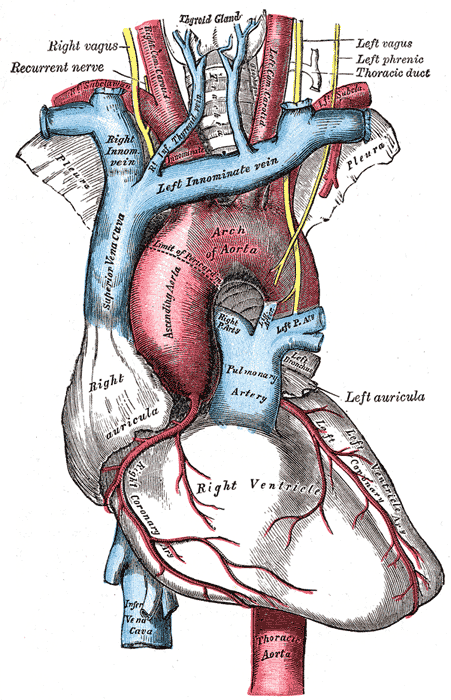

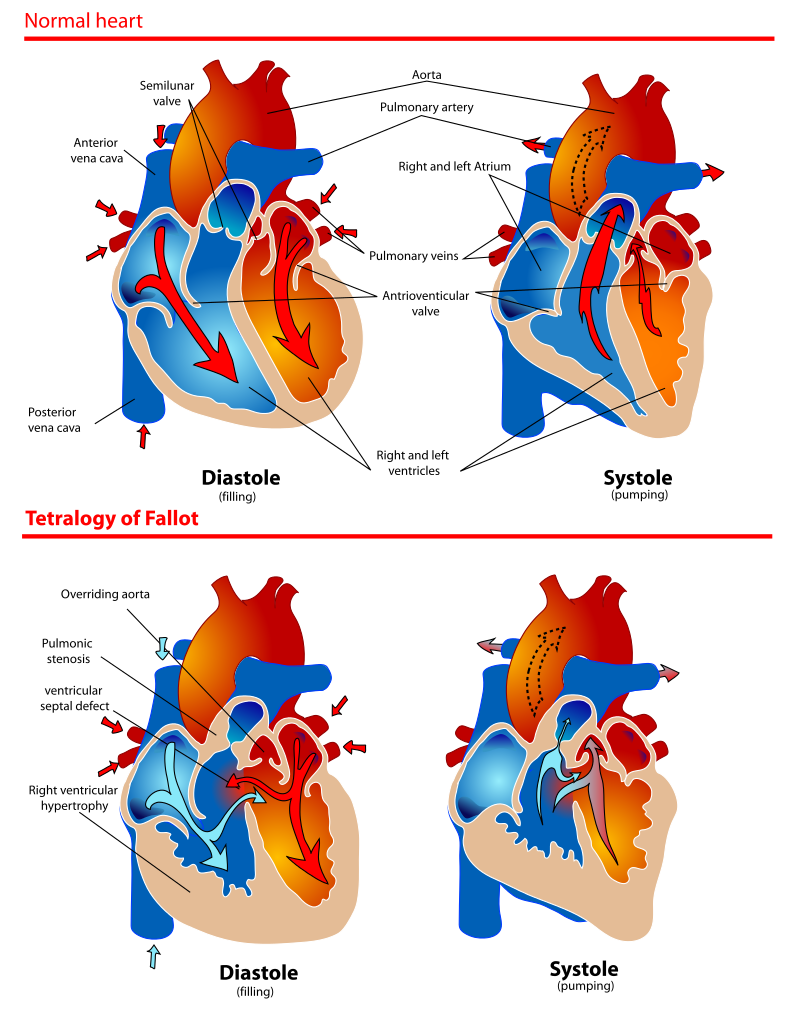

The heart consists of four chambers organized into two pumps (right and left) to provide blood flow to the systemic and pulmonary circulations. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the entire body except for the lungs (the systemic circulation) via the superior and inferior vena cavae. Also, deoxygenated blood from the heart muscle itself drains into the right atrium via the coronary sinus. The right atrium, therefore, acts as a reservoir to collect deoxygenated blood. From here, blood flows through the tricuspid valve to fill the right ventricle, which is the main pumping chamber of the right heart.

The right ventricle pumps blood through the right ventricular outflow tract, across the pulmonic valve, and into the pulmonary artery that distributes it to the lungs for oxygenation. In the lungs, the blood oxygenates as it passes through the capillaries, where it is close enough to the oxygen in the alveoli of the lungs. This oxygenated blood is collected by the four pulmonary veins, two from each lung. All four of these veins open into the left atrium that acts as a collection chamber for oxygenated blood. As with the right atrium, the left atrium passes the blood onto its ventricle both by passive flow and active pumping. Oxygenated blood thus fills the left ventricle, passing through the mitral valve. The left ventricle is the main pumping chamber of the left heart, then pumps, sending freshly oxygenated blood to the systemic circulation through the aortic valve. The cycle is then repeated all over again in the next heartbeat.

All four valves of the heart mentioned above have a singular purpose: allowing forward flow of blood but preventing backward flow.

Conduction System

An electrical conduction system regulates the pumping of the heart and the timing of contraction of various chambers. Heart muscle contracts in response to the electrical stimulus received. The sinus node, which is the main pacemaker of the heart, is situated at the junction of the superior vena cava and the right atrium. It rhythmically generates an electrical discharge about 70 times a minute. This electrical signal is carried to the left atrium via the Bachmann’s bundle. Conduction occurs through the right atrial muscle to the atrioventricular node (AV node), located in the triangle of Koch, a small triangular area formed by the tricuspid valve, tendon of Todaro, and lip of the coronary sinus ostium. The AV node receives the electrical signal and conducts it to the bundle of His with some delay. This delay allows the emptying of the atria into the ventricles before the ventricles contract in response to the electrical signal.

The bundle of His divides into the right and left bundles that successively branch into thousands of small branches called Purkinje fibers. The His-Purkinje tree serves to rapidly conduct the electrical signal to all parts of both ventricles to produce a near-simultaneous contraction of all parts of both ventricles, producing a uniform and coordinated squeeze.[5][6][7][8]

Embryology

The heart develops from two endocardial tubes that merge, loop, and septate to form the heart. During the intrauterine stage, the septum between the two atrial is open, and a ductus connects the pulmonary artery to the aorta, effectively bypassing the pulmonary circulation because the lungs are not functional. Rapidly after birth, these two connections close, establishing separate pulmonary and system circulations.[9]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The heart is supplied by two coronary arteries: the left main coronary artery and the right coronary artery. The left main coronary artery carries 80% of the flow to the heart muscle. It is a short artery that divides into two branches, (1) the left anterior descending artery that supplies anterior two-thirds of the inter-ventricular septum and adjoining part of the left ventricular anterior wall, and (2) the circumflex coronary artery that supplies blood to the lateral and posterior portions of the left ventricle.

The right coronary artery and its branches supply the right ventricle, right atrium, and left ventricle's inferior wall.

Coronary arteries and veins course over the surface of the heart. Most coronary veins coalesce into the coronary sinus that runs in the left posterior atrioventricular groove and opens into the right atrium. Other small veins, called thebesian veins, open directly into all four chambers of the heart.

Small lymphatic vessels form a dense network beneath the epicardium and endocardium of the ventricles and open into a lymphatic duct in the atrioventricular groove. However, the detailed lymphatic anatomy of the human heart has not been worked out.

Nerves

The sinus node and the AV node are both supplied by sympathetic nerve fibers from the sympathetic ganglia and parasympathetic fibers through the vagus nerve and parasympathetic ganglia behind the heart.

Muscles

The heart is a muscular organ. It has no bones. Sheets of muscle fibers are arranged over a fibrous skeleton to give the heart chambers their shapes. However, the atrial muscle is completely separated from the ventricular muscle by a fibrous atrioventricular scaffolding such that no electrical conduction can occur between the two, except through the AV node.

Physiologic Variants

The general structure of the heart is quite uniform in healthy individuals. However, some variations do occur. The heart is arranged more horizontally in the chest in short and obese individuals, while it is more vertical in tall and thin people. An athlete’s heart may be physically larger. Coronary arteries show variations in branching patterns and relative sizes.

Surgical Considerations

Cardiac valves can become fibrosed and calcific with age or disease, producing clinically significant stenosis requiring surgical or trans-catheter replacement. Similarly, valves may become incompetent, allowing backward flow called regurgitation, also necessitating replacement or repair.[10]

Coronary arteries can become clogged with thrombus or atherosclerotic plaque, causing reduced blood supplies to cardiac muscle. This may result in angina or myocardial infarction and often requires revascularization.

Clinical Significance

The heart is a vital organ. If the heart stops, cessation of blood flow and oxygen supply will occur, leading to irreversible brain damage within 4 to 5 minutes. Cessation or impairment of cardiac function may occur due to a lack of blood supply to the cardiac muscle (coronary artery disease), stenosis or regurgitation in cardiac valves (valvular heart disease), intrinsic weakness of heart muscle (cardiomyopathy), or ineffective cardiac rhythms.

Other Issues

In six per 1000 live births, congenital cardiac malformations occur. Ventricular septal defects (VSD), atrial septal defects, and tetralogy of Fallot among the commonest. Tetralogy of Fallot consists of a combination of VSD of the membranous portion of the interventricular septum, stenosis of the orifice of the pulmonary artery, the aortic orifice overriding the VSD, and hypertrophy of the right ventricle. This requires surgical correction, usually at an early age.