Continuing Education Activity

Gastrocnemius injuries are common in both recreational and competitive athletes. This activity outlines the evaluation, treatment, and management of gastrocnemius injuries. It highlights the role of the inter-professional healthcare team in caring for these patients to improve patient outcomes and recovery.

Objectives:

- Describe the mechanism of injury of gastrocnemius ruptures in athletes.

- Outline the evaluation steps for the diagnosis of gastrocnemius ruptures in athletes.

- Summarize the management along with potential complications of caring for patients with gastrocnemius ruptures.

- Identify the importance of improving care coordination amongst the inter-professional team to improve patient care and recovery for patients with severe gastrocnemius injuries.

Introduction

Calf injuries are quite common amongst athletes and involve the gastrocnemius, soleus, popliteal, and plantaris muscles. A gastrocnemius rupture can result in significant pain, limping, and swelling of the posterior calf as well as substantial functional impairment. Proper diagnosis of this injury from other injuries in this anatomical area of the lower leg is essential to efficient management and recovery in athletes.

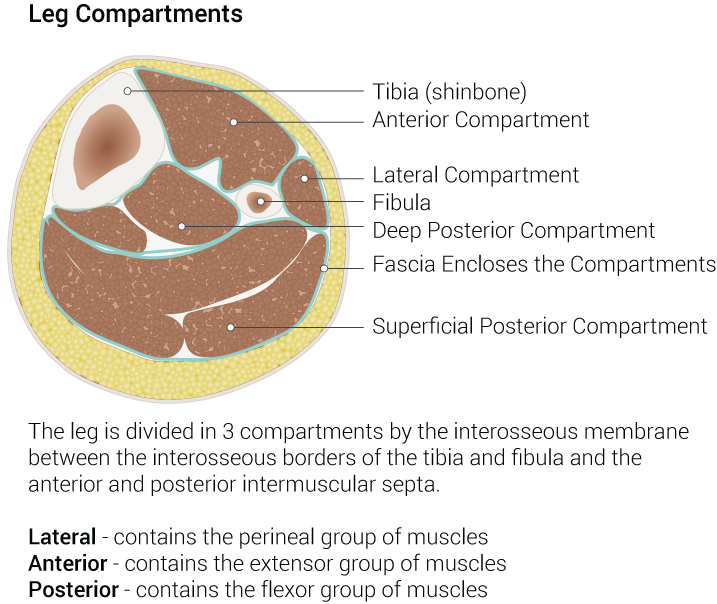

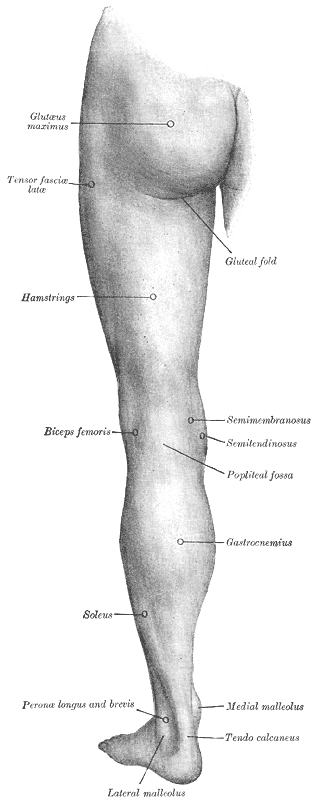

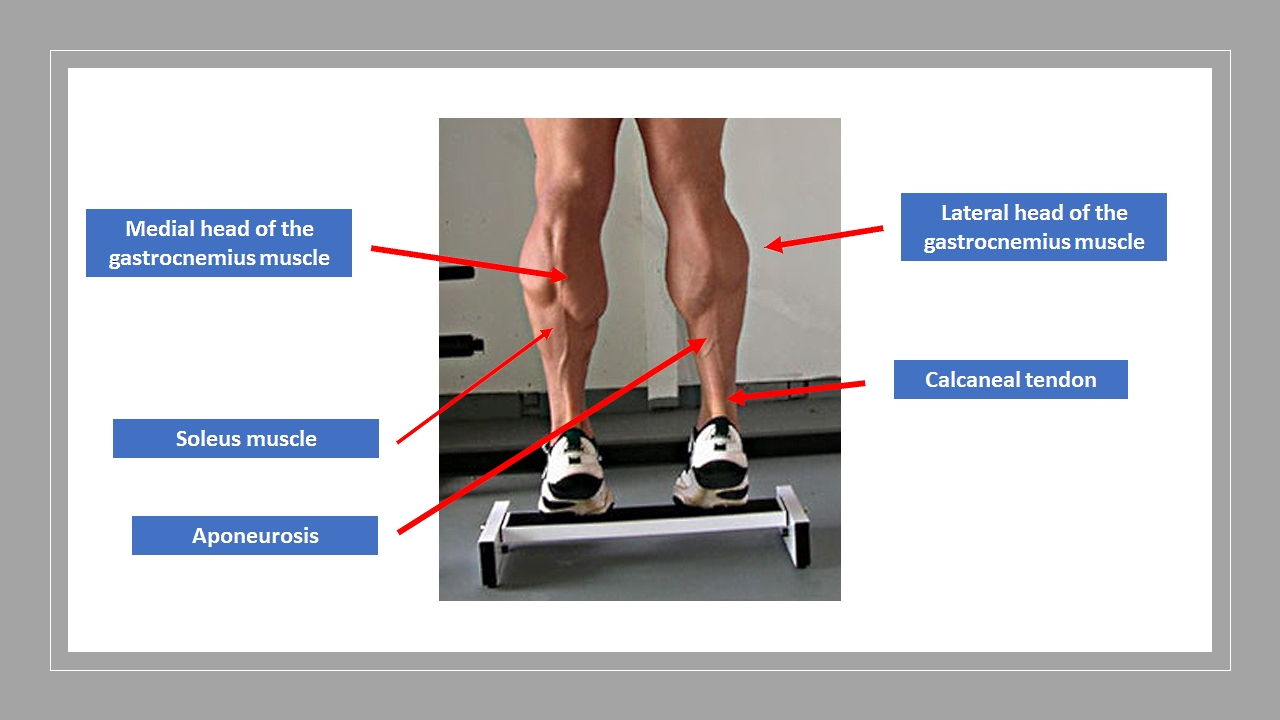

The gastrocnemius is the most superficial muscle and bulky among the muscles in the back (posterior compartment) of the leg. It has two head (lateral and medial) taking origin from the two respective condyles of the femur. Few fibers also take origin from the capsule of the knee joint. The muscle is inserted into the calcaneus bone along with muscle soleus by a common, long, and thick tendon called tendocalcaneus or Achilles tendon. Sometimes the soleus, along with the two heads of gastrocnemius, is considered as a single muscle and referred to as triceps surae.[1]

Supplied by the tibial nerve and posterior tibial artery, this muscle is the chief plantar flexor of the ankle.[2] It was also believed to assist in propelling force during walking. But recent studies clearly signify that the triceps surae do not help in propulsion but only support the body at the time of walking and prevent falling.[3] The medial head is the larger as well as muscular head and has been identified to have more contribution to ankle torques than its counterpart in the sagittal plane.[4]

Etiology

The gastrocnemius is the major muscle of the posterior calf and acts as the primary power generator for running and jumping movements. It consists of fast and slow-twitch muscle fibers. Deep to the gastrocnemius lies the soleus, which contains mostly slow-twitch muscle fibers responsible for maintaining strength and endurance for extended plantarflexion. The plantaris muscle lying between the two heads of gastrocnemius, possess minimal functional capacity but possibly assist with plantar flexion and knee flexion. The popliteus muscle functions to internally rotate the tibia against the femur and inhibit tibia external rotation.[5][6][7][8]

Contact movements that involve a sudden eccentric force can result in gastrocnemius rupture, as occurs during rapid push off or jumping movements when the ankle’s position changes rapidly from a plantarflexed to a dorsiflexed position. This mechanism often happens in tennis players and is termed “tennis leg” in which rapid change of direction, such as when returning a shot, can result in a medial gastrocnemius injury.[9]

Epidemiology

Calf muscle injuries occur commonly in poorly conditioned, middle-aged male athletes. They are common in sports involving explosive lower extremity movements such as football, basketball, tennis, and soccer. They are more common in athletes that are not warmed up adequately or are fatigued. Most injuries occur at the musculotendinous junction of the medial head of the gastrocnemius or the aponeurosis between the medial gastrocnemius and the soleus muscles. A smaller proportion of injuries occur at the lateral head of the gastrocnemius.[5][6][10][11]

Different sports can have a higher predilection for specific calf injuries. An Australian rules football league found that the soleus injury was more prevalent than a gastrocnemius injury, 62% to 24%, respectively. However, a study of US football players found a higher percentage of injuries involving the gastrocnemius (74%), versus the soleus (15%).[12][13]

Other risks associated with calf injury include a prior history of posterior calf strains and older age. A history of lumbar L5 radiculopathy also correlates with an increased risk of gastrocnemius strain among older soccer players.[14][15]

History and Physical

A gastrocnemius rupture can be diagnosed clinically and involves a proximal calf injury after a sudden push off associated with sprinting or jumping. Patients describe symptoms to include a tearing sensation or pop with pain in the calf region. Patients endorse difficulty bearing weight and prefer to walk on their toes to minimize discomfort. Patients complain of calf weakness, increased pain with active plantarflexion or passive dorsiflexion of the ankle, and increased muscular cramping.[6][16]

Physical examination findings include swelling, ecchymosis, and focal muscle tenderness of the proximal calf. Ruptures may present with a palpable defect in the muscle. The patient will have difficulty performing a calf raise. A Thompson squeeze test (used to assess for Achilles tendon rupture) will be negative with normal plantar flexion upon squeezing the calf.[9]

Evaluation

Imaging is typically not needed for diagnosing a gastrocnemius injury, but ultrasound may be helpful to calculate the severity of the injury and to monitor recovery. Ultrasound may show muscle fiber disruption at the musculotendinous junction with a hematoma or fluid collection. A fluid collection appears black and can be present between the soleus and the medial head of the gastrocnemius. The fluid may grow in the first week after the initial injury, and ultrasound can be repeated at subsequent follow-up visits after an injury to assess healing and if swelling is not resolving as expected.[7][16]

MRI is the gold standard for establishing the soft tissue injuries but is only required if the diagnosis of a gastrocnemius rupture is uncertain.[13]

Treatment / Management

Initial treatment involves rest until the patient can walk without limping. A walking boot may be needed for ambulation if the pain is severe. Heel lifts that decrease dorsiflexion and stretch may be helpful. The patient should apply ice for 20 minutes four times daily to decrease swelling with an NSAID or acetaminophen to help with the pain. Compression sleeves that reach 20 to 30 mm Hg may help reduce hematoma formation and may help speed recovery.[17]

Severe injuries associated with an inability to walk are treatable with a progressive physical therapy regimen tailored to the individual’s patient’s level of baseline function and progress. The clinician should assess for swelling and hematoma with ultrasound and calf measurements at the first one week follow up appointment; if present, the patient should continue icing and use of a compression sleeve. The patient can discontinue crutches as tolerated and start walking several times daily. They can begin heel raises and progressively increase their sets and reps with a pain-free goal of 3 sets of 15 repetitions daily, both with knees bent and knees straight. The patient should continue the use of a compression sleeve, heel lifts, and icing until swelling resolves.[17]

The Alfredson protocol involves a progressive eccentric heel drop program and has been well documented for Achilles tendon injury rehabilitation. This protocol can also be an option for gastrocnemius injuries as the calf muscle, and Achilles tendon work together as part of the same musculotendonous complex.[18][19][20]

The patient can start light running if they can perform 15 calf raises on the affected leg with minimal pain and have a normal gait. Light running can progress as tolerated, and the clinician should carefully observe for signs of gait disturbance. The patient can increase running times and distances at a subsequent follow-up visit, but these increases should be gradual, with only minimal increases per week.

There is not a clear goal or cutoff for when the patient should be allowed to return to full play. This progression is generally the recommendation when the patient can perform three sets of 15 heel raises with both bent knee and straight knee of the injured leg without pain; and the ability to run for a half-hour without pain or gait disturbance. The patient can anticipate a full recovery in 3 to 4 months and should continue compression sleeves and heel lifts for several months after return to full play, after which they may elect to discontinue use on their own.[5][6][7][17]

Differential Diagnosis

Broad differential diagnosis of emergent and non-emergent pathology exist for a gastrocnemius rupture. Other calf related muscular injuries include a soleus strain, plantaris strain, or popliteal tendinopathy. A plantaris strain presents similarly to a gastrocnemius strain but is typically less severe, and the pain is located more distally in the mid-Achilles region rather than the proximal calf. Patients will typically have a full or near full range of motion without much pain, and typically will only have mild functional impairment. Ultrasound and MRI can help to make a definitive diagnosis.[16][21]

A soleus strain typically develops from overuse injury secondary to long-distance running in which patients endorse a generalized deep calf pain that increases with knee flexion or ankle dorsiflexion, such as when running up a hill.[6][16]

Popliteal tendinopathy typically develops in a sprint runner who endorses lateral knee or proximal posterior lateral calf pain. Symptoms can be made worse or reproduced from running downhill. Exam reveals tenderness at the popliteal tendon origin at the lateral aspect of the lateral femoral condyle.[22]

Popliteal artery entrapment presents with claudication type symptoms during intense activities that involve repetitive ankle plantar and dorsiflexion that improves with rest. The patient may endorse pedal paresthesias or cold feet. Exam reveals decreased distal pulses during active plantarflexion or passive dorsiflexion.[23][24]

It is important to differentiate a gastrocnemius injury from an Achilles tendinopathy or tear. Tendinopathy presents with a gradually increasing pain along the tendon approximately 2 to 6 cm from calcaneal insertion and is associated with overuse or increased activity. A tendon rupture is quite common in middle-aged adults during a sudden change of direction activities such as tennis, jumping, or sprinting. Patients often hear a “pop,” and physical exam reveals a palpable defect. Patients with complete tears typically cannot fully plantarflex but may be able to do so partially with accessory muscle use. A positive Thompson squeeze test (loss of plantar flexion with calf squeeze) can be useful to diagnose a complete tear. Ultrasound or MRI are also options if the diagnose is still uncertain.

The gastrocnemius, plantaris, and soleus are the muscles of the superficial posterior compartment of the leg. It is essential to rule out acute compartment syndrome (ACS), which presents with rapidly worsening leg pain. It is most commonly associated with trauma but can also be non-traumatic. The physical exam includes a tense, painful muscle compartment with pain out of proportion to the exam. Suspected ACS requires emergent surgical consultation.

Other musculoskeletal diagnoses to consider include chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS), exercise-associated muscle cramps, medial tibial stress syndrome, and osteomyelitis. CECS presents in runners with an increasing, deep pain within a specific area of the calf or shin, is often bilateral, begins with activity, ends 10 to 20 minutes after activity cessation, and may be associated with ankle and foot paresthesias. The physical exam is often benign. Diagnosis can be made by measuring intra-compartmental pressures.

The non-musculoskeletal causes to consider include claudication, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and peripheral nerve entrapment. DVT presents with worsening pain and swelling of the calf without a history of injury; however, several case reports have associated DVT with calf injuries. Patients with DVT have more generalized swelling over the calf and lack focal tenderness typically associated with acute calf strains.[25][26]

Prognosis

Most gastrocnemius injuries heal without complications, with an average healing time of several weeks to 3 to 4 months. Complete ruptures or large hematomas take longer to recover. The majority of players will return to full activity if adherent to prescribed physical therapy regimens.[27]

Complications

Emergent complications are rare but can include acute compartment syndrome or DVT. Non-emergent complications can rarely include myositis ossificans, calf atrophy, and more commonly mild calf weakness. Some patients endorse chronic calf tightness with sharp pains during exercise after recovery.[25][26][28]

Consultations

A gastrocnemius rupture rarely requires surgical repair. Emergent orthopedic consultation is necessary for suspected compartment syndrome. Patients need a vascular surgery consultation for suspected popliteal artery entrapment.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education during rehabilitation is vital to recovery. Physical therapy should be custom-made to the individual patient, which will vary based on the patient's age, baseline functional levels after injury, and the ability to recover. The clinician should carefully monitor the patient's gait, work volume, and rest periods throughout therapy so that the athlete does not overwork beyond prescribed limits leading to delayed healing, slower recovery, or reinjury.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Gastrocnemius tears can result in significant functional impairment for athletes, if not diagnosed and treated appropriately. Interprofessional communication and patient education are essential. The condition can be recognized and treated by multiple clinicians to include primary care physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, orthopedics surgeons, and physical therapists. It is important to rule out emergent conditions such as acute compartment syndrome or deep vein thrombosis and to distinguish the injury from a calcaneal tendon rupture. With adequate interprofessional communication and patient education, gastrocnemius tears can be diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion to improve patient recovery.