Continuing Education Activity

Goodpasture syndrome, also referred to as anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease, is an autoimmune disease that affects both the kidneys and lungs by the formation of autoantibodies that attack their basement membranes. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of Goodpasture syndrome and explains the interprofessional team's role in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the role of autoantibodies against glomerular basement membranes in the pathophysiology of Goodpasture syndrome.

Explain the use of kidney biopsy in the evaluation of Goodpasture syndrome.

Review the management of Goodpasture syndrome.

Summarize the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by Goodpasture syndrome.

Introduction

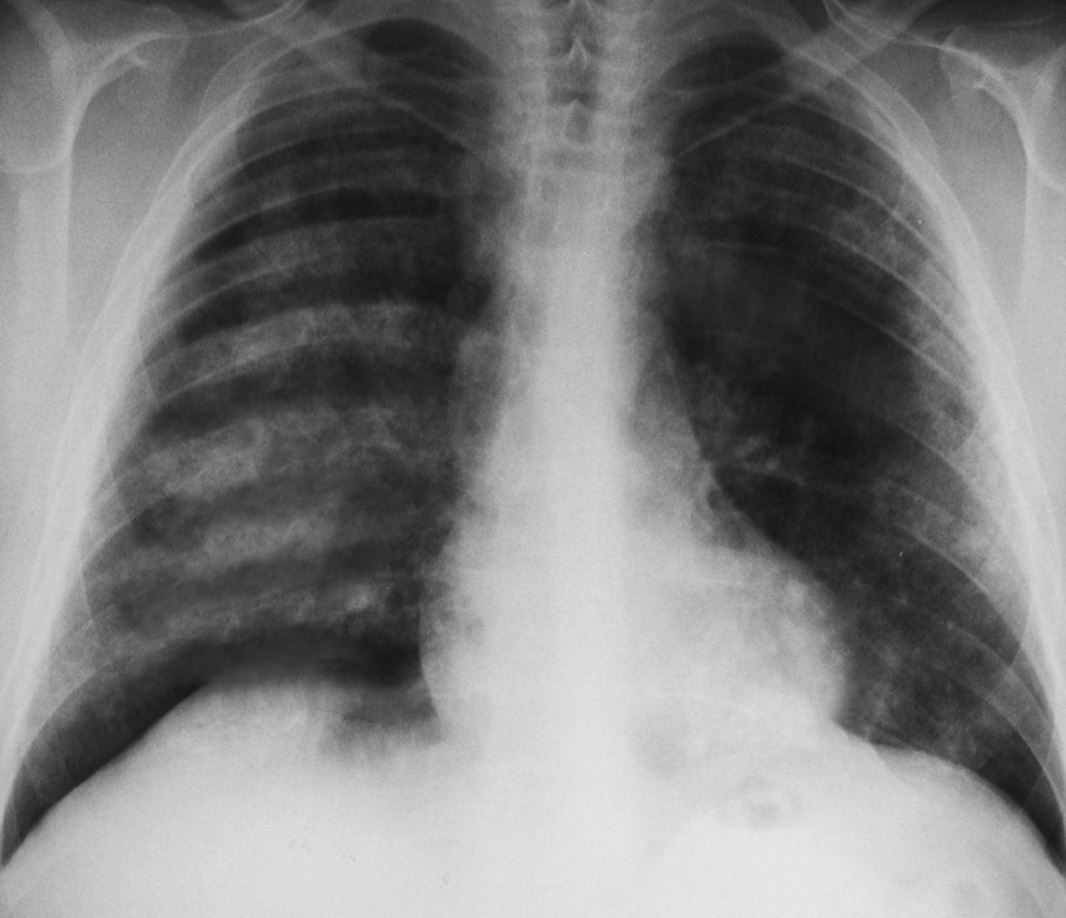

Goodpasture syndrome refers to an anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease that involves both the lungs and kidneys, often presenting as pulmonary hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis (see Image. Pulmonary Hemorrhages, Goodpasture Syndrome. Chest x-ray showing pulmonary hemorrhages seen in Goodpasture syndrome). However, some clinicians may interchangeably use several terms, including anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, Goodpasture syndrome, and Goodpasture disease.[1] The anti-GBM disease is the most specific term and refers to the presence of renal and pulmonary involvement, along with anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies. The spectrum of disease may present classically or as glomerulonephritis alone.

Goodpasture syndrome is an eponym named after Ernest Goodpasture, who described this disorder for the first time in 1919. Later the discovery of anti-GBM antibodies led to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of Goodpasture syndrome.

Etiology

Goodpasture syndrome appears to result from environmental insults in a person with a genetic predisposition. At this point, a triggering stimulus has not been identified for the development of anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies. However, there are certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) subtypes that have been implicated in conferring increased genetic susceptibility to Goodpasture syndrome, most notably HLA-DR15.[2] The exposure of the alveolar capillaries to these autoantibodies needs an initial insult to the pulmonary vasculature. These environmental factors include:

- Drugs, such as alemtuzumab that causes lymphocyte-depletion

- Inhalation of cocaine

- Infections, such as influenza A2

- Smoking

- Exposure to metal dust, organic solvents, or hydrocarbons

- Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy[3]

Epidemiology

Goodpasture syndrome is a rare disorder. The incidence of the anti-GBM disease is approximately 0.5 to 1.8 cases per million per year in Asian and European populations. It is responsible for 1-5% of all kinds of glomerulonephritides. Furthermore, it accounts for 10%-20% of crescentic glomerulonephritis.[4][5]

Race, Gender, and Age-related Distribution

Goodpasture syndrome is seen more commonly in Whites than in the Black population, however, it may be more prevalent in certain ethnicities, such as the Maori people of New Zealand. The syndrome has bimodal age distribution, 20-30 years and 60-70 years. The occurrence of the disease is more in younger men and older women.

There is a subgroup of patients that is double-positive for both antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-GBM antibodies. This subgroup is mainly found in males 60-70 years old.

Pathophysiology

Goodpasture syndrome is due to circulating autoantibodies directed at the glomerular basement membrane. The resulting crescentic glomerulonephritis is the result of the antigen-antibody complexes that form at the basement membrane.[6] The autoantibodies activate the complement system in the basement membrane, causing tissue injury. This binding of autoantibodies can be seen as a linear deposition of immunoglobulins along the basement membrane. The inflammatory response in that area results in the typical picture of glomerulonephritis.

The alveolar basement membrane shares the same collagen target as that of the glomerulus. The main component of the basement membrane is type 4 collagen, which can be expressed as six different chains, from alpha 1 to alpha 6. Despite the presence of circulating antibodies in anti-glomerular basement membrane disease, pulmonary symptoms are not always observed. An inciting lung injury seems to make pulmonary symptoms more likely.

In a healthy individual, the alveolar endothelium acts as a barrier to the anti-basement membrane antibodies. However, if an insult results in increased permeability of the alveolar capillaries, it leads to the trespassing of autoantibodies, which then bind to the basement membrane. The factors that may result in an increased alveolar-capillary permeability include:[7]

- Increased capillary hydrostatic pressure

- Bacteremia

- Tobacco smoking

- Endotoxemia

- Exposure to volatile hydrocarbons

- Upper respiratory tract infections

- Higher inspired oxygen

Strong evidence for genetic involvement exists and patients with certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) types are found to be more susceptible to disease and exhibit a poor prognosis.

An increased prevalence of HLA-DR15, DRB1*03, and DRB1*04 has been found and a reduced frequency of DRB1*01 and DRB1*07.[8][9] Goodpasture syndrome has a strong association with DRB1*1501 and to some extent DRB1*1502 allele. However, DRB1*1501 allele is present in one-third of people among Whites. Therefore clearly some additional factors, such as genetic or environmental, are needed for the expression of disease. It is important to note that HLA-B7 is seen more frequently and indicates more severe anti-GBM nephritis.

Although Goodpasture syndrome is regarded as an autoantibody-mediated disease, a vital role is played by T cells have in the initiation and progression of the disease. T cells cause B-cells to increase antibody production and play a direct role in the renal and pulmonary injury.[10]

Histopathology

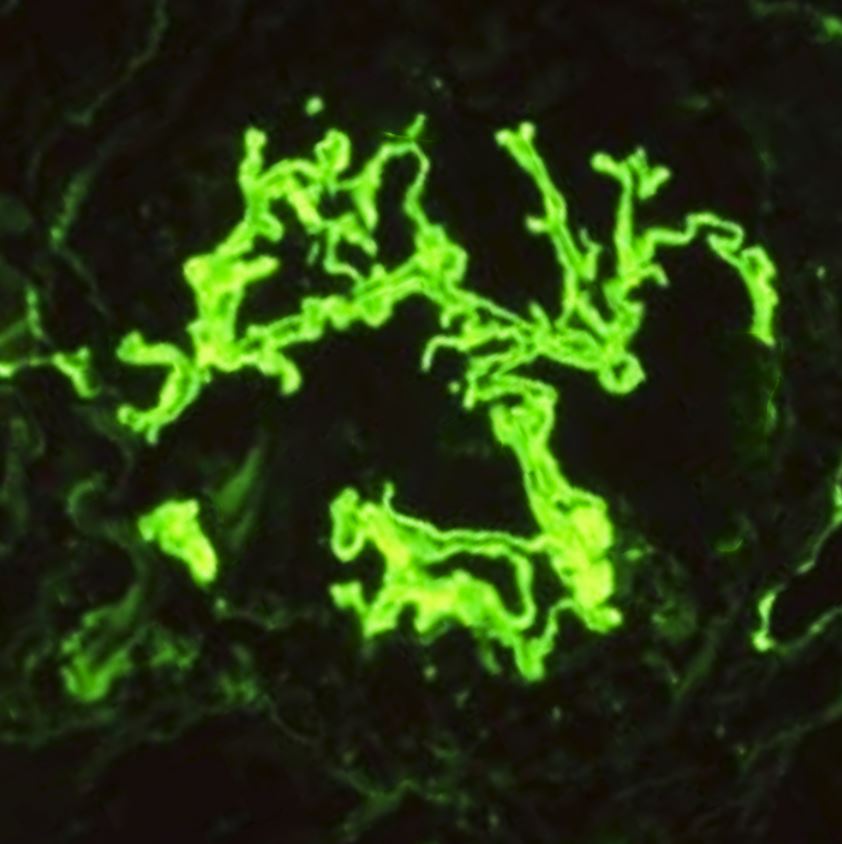

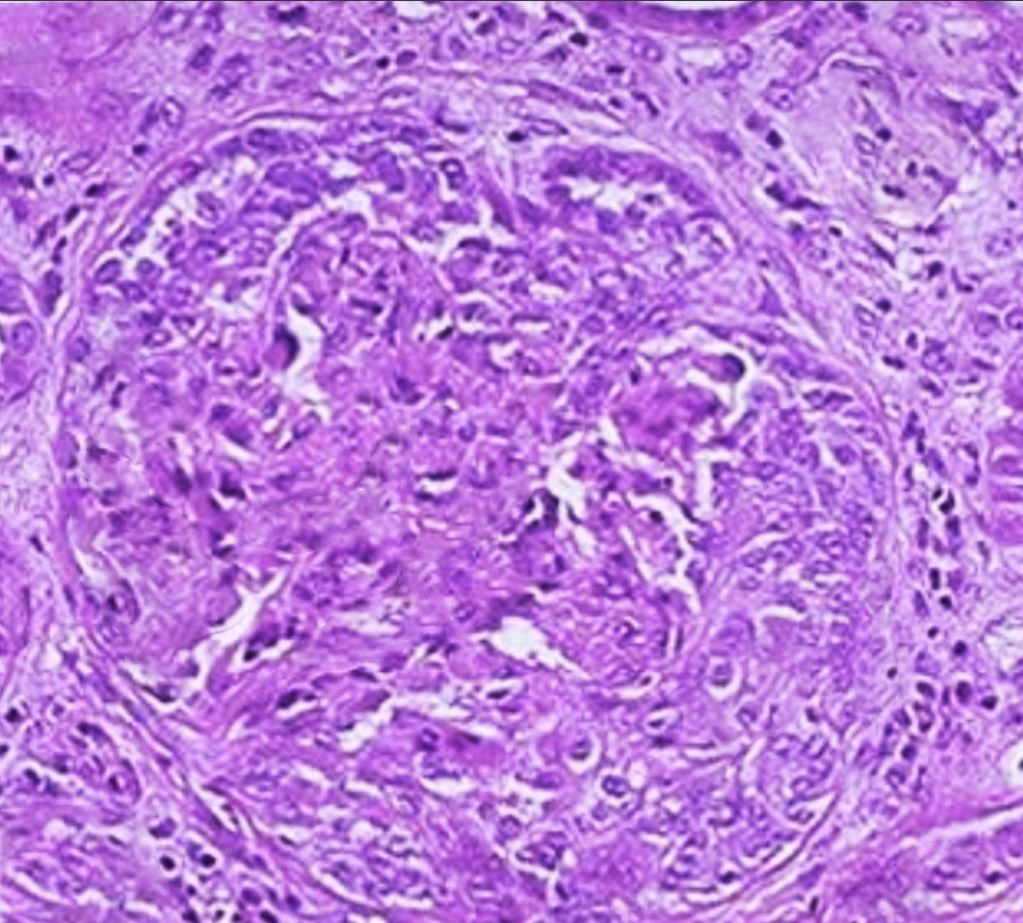

In patients where renal and pulmonary involvement raises suspicion of Goodpasture syndrome, renal biopsy should be considered, which has a better yield than lung biopsy. Light microscopy will show crescentic glomerulonephritis (see Image. Crescentic Glomerulonephritis). Over time, the crescents turn fibrotic, and frank glomerulosclerosis with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy may be appreciated. Immunofluorescence will show the linear deposition of IgG and complement (C3) along the basement membrane. Predominantly, subclass IgG-1 is present.[11] See Image. Immunofluorescence Staining for IgG.

A kidney biopsy is not only crucial for diagnosis, but the percentage of crescents identified on biopsy confers renal survival prognosis. Lung tissue is typically not sought due to the invasiveness of the procedure and a more difficult immunofixation process for lung tissue. Lung biopsy, when performed, shows extensive hemorrhage with deposition of hemosiderin-laden macrophages within alveolar spaces.

History and Physical

Patients with Goodpasture syndrome will initially present similarly to other forms of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with acute renal failure. There are no symptoms specific to the anti-glomerular basement membrane that distinguish it from other diseases causing similar organ dysfunction. Careful and expedient workup must be undertaken for an accurate diagnosis. The pulmonary symptoms are typically present at the time of the initial encounter or shortly after that. Hemoptysis of varying degrees is typical for pulmonary involvement, ranging from serious and life-threatening bleeding to more subtle diffuse hemorrhage that is only apparent on more careful evaluation. It is more typical for younger patients affected by the anti-glomerular basement membrane disease to present with simultaneous renal and pulmonary symptoms (Goodpasture syndrome) and to be critically ill on presentation. Patients over 50 years old tend to present with glomerulonephritis alone and follow a less severe course.

Careful physical examination of patients presenting with findings suspicious for the anti-glomerular basement membrane disease should be done, particularly for other signs such as a purpuric rash. This finding may suggest so-called “double-positive” patients with concurrent ANCA-associated vasculitis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis). Other physical exam findings to look for in Goodpasture syndrome are:

- Increased respiratory rate

- Basilar inspiratory crackles

- Cyanosis

- Hepatosplenomegaly

- Hypertension (in 20% of cases)

- Edema

Evaluation

A kidney biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis but is not required to begin treatment or continue therapy if a biopsy is not feasible. When performed, biopsy provides important information regarding the activity and chronicity of renal involvement that may guide therapy. Percutaneous kidney biopsy is the recommended procedure to establish the diagnosis of Goodpasture syndrome. Kidney biopsy is preferable over lung biopsy as it provides a much higher yield, but lung biopsy may be performed where renal biopsy is contraindicated for any reason.

The biopsy tissue should be sent for analysis under light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence. Light microscopy shows nonspecific findings of a proliferative or necrotizing glomerulopathy with cellular crescents (as shown in the image). The crescents become fibrotic over time leading to the development of frank glomerulosclerosis, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis.

Immunofluorescence stains are more specific and diagnostic. These exhibit bright linear deposits of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and complement (C3) on the glomerular basement membrane.[11]

Serologic testing for ELISA assay for circulating anti-GBM antibodies should be done immediately on suspicion of the disease. Specifically, it is essential that the alpha3 NC1 domain area of collagen 4 be used as the target in this assay as false positives may be seen in less specific testing.[12] Quantitative titers are followed during treatment phases to guide treatment decisions.

- Urinalysis is characteristic and usually demonstrates low-grade proteinuria, gross or microscopic hematuria, and RBC casts.

- A complete blood count may reveal anemia secondary to intrapulmonary hemorrhages, and leukocytosis is generally present.

- Renal function tests may be deranged secondary to renal dysfunction.

- A chest radiograph shows patchy parenchymal opacifications, which are usually bilateral and bibasilar. The apices and costophrenic angles are generally spared.

- Pulmonary function tests show elevated diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) secondary to binding of carbon monoxide to intra-alveolar hemoglobin.

Treatment / Management

Patients presenting with Goodpasture syndrome (both glomerulonephritis and pulmonary hemorrhage) may be critically ill on presentation. Urgent hemodialysis often is needed for standard indications, and intubation for respiratory failure may be necessary. When the clinician suspects the diagnosis, a kidney biopsy should be done as soon as the clinical situation allows.

Upon diagnosis, patients should be started on prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and daily plasmapheresis to improve overall mortality in general and renal survival in particular.[13][14][15] If therapy can start before the patient progresses to needing renal replacement therapy, the overall renal prognosis is better. All patients with pulmonary symptoms should be started on combined therapy regardless of their renal status. For patients without pulmonary symptoms in whom renal recovery is very unlikely (i.e., for those that presented with the urgent need for dialysis within the first 72 hours), the risk of plasmapheresis and immunosuppressive may outweigh the benefits. The choice to withhold treatment in these cases remains controversial as the disease has not been well-studied in controlled trials. It remains difficult to predict who in this group exactly will respond and recover renal function. The overall return of renal function in this group is approximately 8%, yet many clinicians still opt for a trial of aggressive combined therapy at this time.

Typically, daily plasmapheresis is performed until anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies are undetectable, with steroid and cyclophosphamide continuing after that for 3 to 6 months until full remission is achieved. This can be gauged by checking repeated titers following plasmapheresis, as well as any time new symptoms develop that could be a harbinger of relapse. Overall, relapse remains rare. The starting dose of cyclophosphamide is 2 mg/kg orally, adjusted to keep a white cell count of approximately 5000. Treatment of acute life-threatening alveolar hemorrhage is with IV methylprednisolone pulse therapy 1g/day for 3 days, followed by a tapering dose at 1 to 1.5 mg/kg orally.

Rituximab has been found to have a role in some studies in which the conclusion was that it led to the undetectable levels of anti-GBM antibodies.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

All the pulmonary-renal syndromes that affect the lung and kidney are to be considered in the differentials. These include:

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Microscopic polyangiitis

Some patients with Goodpasture syndrome also have ANCAs positive, which makes it difficult to distinguish it from granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[17]

Some IgA-mediated disorders also present with pulmonary-renal syndromes, such as:

- IgA nephropathy

- Henoch-Schonlein purpura

Other differential diagnoses include:

- Acute glomerulonephritis

- Community-acquired pneumonia

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Churg-Strauss syndrome

Prognosis

With the development of aggressive therapies such as plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents, the prognosis of Goodpasture syndrome has significantly improved.[18] With these therapies, the 5-year survival rate has exceeded 80%, and less than 30% of patients require long-term dialysis. However, delayed administration of cyclophosphamide has been found to be associated with a fatal prognosis.[19]

Complications

Even with appropriate treatment, kidney function may be impaired to the point of failure. While kidney failure is a relatively common complication for patients with Goodpasture syndrome, less than 30% of surviving patients require long-term dialysis. In severe cases, a kidney transplant may be necessary.

Consultations

A nephrologist should be consulted for the evaluation of a patient in terms of:

- Differential diagnosis of the renal disease

- Indication for renal biopsy

- Requirement for hemodialysis

- Plasmapheresis

As these patients may present with serious and life-threatening pulmonary complications, a pulmonologist should be consulted to guide therapy.

A surgeon's assistance may also be needed when vascular access is needed for hemodialysis or plasmapheresis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be made aware of the treatment options available. Many immunosuppressive medications have various adverse effects that patients should know about. They should be educated on when to seek medical help in order for management to happen sooner than later. In some patients, it recurs so giving patients a basic knowledge of how to pick signs of Goodpasture syndrome may help them pick a relapse quickly and seek help.

Pearls and Other Issues

The prognosis for this spectrum of diseases is overall good, provided the disease is identified efficiently, and treatment started promptly—overall survival and renal recovery track along with the degree of renal impairment on presentation.

Recurrence is rare but possible, and patients typically do well with recurrent episodes. This is most likely due to heightened clinical suspicion. Treatment in recurrent cases is identical to the initial episode.[20]

Patients that do not recover renal function and remain dependent on renal replacement therapy may qualify for renal transplantation. Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody titers should be negative for at least six months before transplantation.[21] These patients rarely experience recurrent disease in the current era following transplant, but it has been reported in the literature.[5] It has been theorized that long-term use of immunosuppressive agents intended to protect the graft from rejection simultaneously keeps the autoimmune disease from recurring.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of Goodpasture syndrome requires careful coordination of several specialties. The involvement of pulmonary/critical care, nephrology, and rheumatology should be sought depending on the spectrum of clinical findings and the severity of the disease. An interprofessional team consisting of clinicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists will provide the best results. [Level 5] Transfer to a center capable of providing input from those specialties is advisable. Plasmapheresis, if indicated, should be sought. Initial lab assays should be expedited, and protocols should be put in place for all team members to be aware of positive test results and act on them immediately.