Continuing Education Activity

Perilunate dislocations (PLDs), lunate dislocations (LDs), and perilunate fracture-dislocations (PLFDs) are rare high-energy injuries. Because these injuries have the potential to cause lifelong disability of the wrist, early recognition and diagnosis are prudent to restore patient function and prevent morbidity. This activity describes the evaluation and management of perilunate dislocations and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of perilunate dislocations.

- Outline the common presenting symptoms and radiographic findings of perilunate dislocations.

- Summarize the complications and long-term sequelae of perilunate dislocations.

- Identify the importance of recognition and collaboration amongst the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients presenting with perilunate dislocations.

Introduction

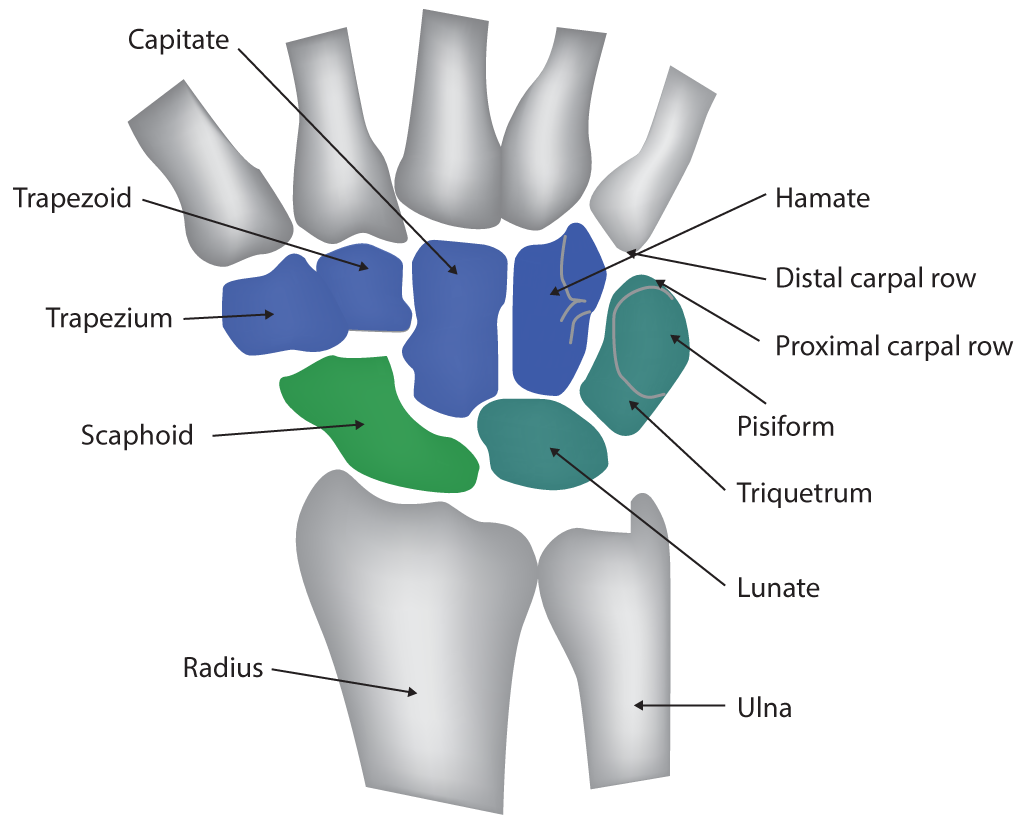

Perilunate dislocations (PLDs), lunate dislocations (LDs), and perilunate fracture-dislocations (PLFDs) are rare high-energy injuries constituting less than 10% of all wrist injuries.[1] The carpus consists of two rows of bones: proximal and distal. The proximal row, which is the more mobile of the two, articulates with the distal radius and moves in concert with the distal radius and ulna. The scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum serve as the connecting bones that make up the proximal row. The more rigid distal row—which contains the trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, and hamate serves as a bridge between the proximal row and metacarpal bases. The carpus’ stability is maintained through its bony articulations and intrinsic and extrinsic ligaments. As its name suggests, the lunate is a semilunar bone with a crescent shape. Its proximal end is convex and articulates with the concave lunate facet of the distal radius. The distal articular surface is concave and articulates with the capitate. Bordered by the scaphoid radially and the triquetrum to its ulnar border, the lunate is attached to the scaphoid and triquetrum by the intrinsic scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligaments, respectively. Palmar attachments include the radiolunotriquetral, radioscapholunate, and ulnolunate extrinsic ligaments.[2] The lunate serves as a center keystone and link between the forearm and the hand.

In general, PLDs occur through injuries to the surrounding stabilizing structures, such as through fractures and disruptions in articulations or ligaments. The surrounding carpal bones most commonly dislocate dorsally, and the lunate maintains its articulated position with the distal radius. Alternatively, albeit rarely, the lunate can dislocate in the volar direction into the space of Poirier. Because these injuries have the potential to cause lifelong disability of the wrist, early recognition and diagnosis are prudent to restore patient function and prevent morbidity. Early treatment may prevent or lessen the chance of median neuropathy, post-traumatic wrist arthrosis, chronic instability, and fracture nonunion. Nonoperative treatment is rarely indicated and is associated with poor functional outcomes and recurrent dislocation.

Etiology

As described in biomechanical studies, the mechanism of injury for PLDs is forced hyperextension, ulnar deviation, and intercarpal supination of the wrist.[3][4] A PLD is the result of high-energy trauma, such as that occurring in motor vehicle accidents, falls, athletic injuries, and industrial accidents.[5]

Epidemiology

Because PLDs are frequently missed, their true incidence is unknown. Furthermore, PLDs lack their own diagnosis code, and as such, they are grouped under mid-carpal joint dislocations in both the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 and ICD 10. This classification makes it difficult to aggregate epidemiological data. In general, fracture-dislocations of the carpus are uncommon as compared to fractures of the distal radius, metacarpals, and phalanges. Fractures and fracture-dislocations of the carpus have an annual incidence of 37.5 per 100,000 persons and constitute 2.8% of all fractures. Perilunate injuries are estimated to represent less than 10% of all wrist injuries.[1]

Pathophysiology

This injury progresses through several distinct phases, known as the Mayfield progression, and may involve the greater or the lesser arc of the carpus.[6] Greater-arc injuries, which produce fracture variants of the scaphoid, capitate, and radial styloid, were initially described by Mayfield as the result of a relatively slower axial load. The scaphoid is the most common carpal bone fracture associated with PLDs (61%), termed a trans-scaphoid or de Quervain injury, which can further complicate treatment.[7][8][9] By contrast, lesser-arc injuries were thought to develop from more rapidly applied forces and progress as injuries to the ligamentous structures about the lunate.[6]

The injury begins with a traumatic disruption of the scapholunate joint and subsequently progresses to the capitolunate, lunotriquetral, and radiolunate joints. When the perilunate ligaments rupture and a PLD occurs, the palmar ligaments maintain the position of the radiolunate joint, and the remainder of the carpus dislocates dorsally. Alternatively, when the radiolunate joint is disrupted, an LD can result, usually occurring in the volar direction and transposing into the carpal tunnel. Although described as a progression of injury, perilunate dislocation can involve bony structures, ligaments, or a combination of bony structures and ligaments.

History and Physical

The diagnosis of PLD is missed on clinical and radiographic evaluation in up to 25% of cases, leading to ruinous complications.[8] Patients with perilunate injuries often present with decreased range of motion, swelling, pain, and a palpable deformity of the wrist. Depending on the spectrum of disease, the described symptoms can vary. If the distal carpal row dissociates dorsally, a deformity may be visible at that level. If the lunate dislocates in a volar direction, a deformity and palpable bony prominence can be felt within the carpal tunnel.

Obtaining a full history is prudent to better understand the mechanism of injury and rule out associated injuries, which can be present in up to 26% of cases.[10] A thorough neurovascular examination of the affected upper extremity should be performed. A significant association (29–45%) exists between PLDs and acute carpal tunnel syndrome.[8][11][12][13] Patients with compression of the median nerve may complain of paresthesias of the palmer surface of the first three digits. Assessment of the motor function of the hand can be limited secondary to pain.

Evaluation

Upon completion of a thorough history and physical exam, radiographic evaluation aids in diagnosis. Conventional radiographs should be obtained in multiple orthogonal views as tolerated, including posteroanterior (PA), lateral, oblique, and scaphoid.[14] The images should be scrutinized for any abnormalities. Several classic radiographic abnormalities may be noted. On the PA view, abnormal widening of the scapholunate interval > 3 mm (i.e., Terry Thomas sign) can be indicative of a scapholunate ligament injury. Additionally, a loss of normal carpal collinear arc lines (Gilula lines) should raise suspicion for carpal injuries.[2] The first arc of Gilula traces the proximal scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum. The second arc aligns with the distal border of the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum, and the last arc traces the confluence of the proximal border of the capitate and hamate.[2][15]

The lunate can appear triangular in appearance when it rotates, an appearance known as the “piece-of-pie sign.”[14] The lateral radiograph should determine whether a colinear line forms the distal radius articular surface, lunate, capitate, and third metacarpal shaft. Any disruption of this alignment should raise suspicion for carpal instability or malalignment. Furthermore, on the lateral view, the classically described “spilled teacup sign” may be noted with volar dislocation of the lunate.[14]

Computerized tomography (CT) can be helpful to further appreciate the personality of the fracture patterns in PLFDs. CT can also aid in preoperative planning, and 3D reconstruction of CT films has become an evolving technology for surgeons. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is both sensitive and specific for detecting ligamentous injuries and occult fractures that are missed on conventional radiographs and CT scans. Advanced imaging should be obtained after closed reduction.[16]

Treatment / Management

Initial management of PLDs involves an emergent closed reduction of the dislocation and immobilization of the wrist. The reduction can be difficult and require the application of traction weights to the arm, with the hand suspended as a form of counter traction. Sedation is frequently necessary to increase the chance of a successful reduction.[16] The reduction maneuver is partially dependent on pathophysiology. For volar LDs, the wrist is extended with consistent traction while dorsally directed force is simultaneously placed on the lunate bone. Next, the wrist is brought into flexion while the force on the lunate bone is maintained to direct it into the fossa. For PLDs where the lunate remains in the fossa but the distal row has dislocated dorsally, a reduction can be obtained with a similar mechanism to relocate the dorsal carpal bones into alignment with the lunate. Once closed reduction is obtained, splint immobilization is required. Studies have shown that closed reduction followed by immobilization infrequently results in acceptable patient outcomes.[17]

As a general consensus, nonoperative treatment is rarely indicated as definitive management. Operative management of PLDs and PLFDs in the acute setting (less than eight weeks) is generally indicated. The goals of operative management are confirmation of reductions, ligamentous repair/reconstructions, fixations of associated fractures, and supplemental fixations of the bony architecture to allow for ligamentous healing. Surgery can be done through volar, dorsal, or combined volar and dorsal approaches combined with carpal tunnel release. Despite operative management generally being agreed upon, surgical approaches remain more controversial. Several studies have demonstrated comparable outcomes; thus, the choice of approach is largely influenced by surgeon preference.[11][12][18][19]

Chronic PLDs or missed injuries can be treated with attempted open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) or with salvage procedures, such as scaphoid removal and four-corner fusion, proximal row carpectomy, and total wrist arthrodesis.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of wrist injury is broad, underscoring the importance of proper history, physical exam, and radiographic evaluation. Wrist pain after an injury can be the result of intrinsic or extrinsic ligament sprains or tears, triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries, osteochondral cartilage injuries, lunotriquetral ligament instabilities, or scapholunate dissociations, to name a few. Radiographic evaluation aids in ruling out fractures of the proximal or distal carpal rows, of which scaphoid fractures are the most common. Distal radius fractures and metacarpal base fractures can also be seen. Treatment is entirely dependent on the appropriate diagnosis. Therefore, keeping an appropriate differential in mind is essential.

Prognosis

PLDs are severe injuries to the wrist, and the patient should be counseled accordingly. Closed treatment has been shown to have inferior outcomes to open treatment. Apergis et al. reviewed 28 patients with PLD and found that the 8 treated with closed reduction and casting had fair-to-poor outcomes at a six-year follow-up.[17] The remainder of the patients, who were treated with ORIF, had good-to-excellent results. Even in the setting of acute reduction and adequate fixation, a number of barriers can hinder prognosis and lead to unfavorable outcomes. Herzberg et al. retrospectively reviewed 166 PLD and PLFD cases in a multicenter study with a mean follow-up of six years.[8] They identified some key factors influencing outcomes. Open injuries had lower mean clinical scores relative to those of closed injuries treated within one week of the injury. Compared to injuries treated within one week of injury, those with delays in treatment were associated with worse clinical outcome scores.

Radiographically, 71% of patients had persistent unsatisfactory films, and 56% had identifiable post-traumatic arthritis, which was unassociated with poor clinical outcomes.[8] However, all of the satisfactory radiographs correlated with good or excellent clinical results. Krief et al. reviewed 30 patients with PLD or PLFD, with a mean 18-year follow-up.[20] In regard to motion, the mean flexion-extension, radial-ulnar, and pronation-supination arcs compared to the uninjured were 68%, 67%, and 80%, respectively. Mean grip strength was 70% that of the contralateral uninjured hand. Radiographic arthritis was seen in around 70% of patients. However, on the basis of functional scores, its impact is inferred to be low, with no clear correlation between radiographic arthritis and disability. The most concerning result was that 6 patients (20%) at follow-up had developed complex regional pain syndrome, which can lead to severe disability of the affected extremity.[20]

Complications

A number of complications are associated with PLDs and PLFDs. Acute median neuropathy via acute carpal tunnel syndrome is common and requires a surgical release. Median neuropathy has a prevalence of 22–33% and is most common in stage IV injuries, in which the lunate dislocates from the lunate fossa into the carpal tunnel. Studies have shown various prevalence ranges from 29 to 45% in all comers of PLDs and PLFDs.[8][11][12][13] Sustained median nerve irritation, post-traumatic arthritis, transient lunate ischemia, osteonecrosis, chondrolysis, chronic perilunate instability, and complex regional pain syndrome are all complications associated with poor prognosis and thus should be monitored closely following PLDs.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education involving patients, the general public, and healthcare providers is necessary to provide the best patient outcomes according to evidence-based medicine.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Enhancing interprofessional team outcomes is important in the continuity of care for patients with perilunate dislocations. These patients can present to the emergency department, urgent care, or to their primary care provider for initial injury evaluation. It is of utmost importance that the recognition of these injuries is appreciated. The diagnosis is missed on initial clinical and radiographic evaluation in up to 25% of cases. Early recognition and diagnosis of these injuries are prudent to restore patient function and prevent morbidity.