Continuing Education Activity

Optic atrophy is the hallmark of damage to the visual pathway. It appears as a pale disc on fundus examination. This clinical appearance is not a disease, per se—it only indicates damage to the anterior visual pathway, which can occur in several conditions. This activity delves into the pathophysiology of optic atrophy, clarifying the complexities surrounding its development and showcasing it as the end result of retinogeniculate pathway degeneration. The course discussion also addresses the misnomer associated with the term "optic atrophy" in favor of "optic neuropathy," and elucidates the mechanisms contributing to disc pallor, including neuro-vascular degeneration and the loss of axonal fibers. By explaining the optic nerve's behavior, this activity offers insights into the unique challenges associated with regeneration in the central nervous system, essential for effective clinical management strategies.

Timely diagnosis of optic atrophy is critical. This activity underscores the multidisciplinary approach required for managing optic atrophy, stressing the importance of early identification of underlying causative factors. It explores various systemic and ocular conditions associated with optic atrophy, emphasizing the need for proper history-taking and comprehensive examinations for optimal patient care. Additionally, potential interventions tailored to the specific etiologies—ranging from low vision aids to specialized nursing care—are covered, underscoring the importance of an interprofessional team in addressing this condition. By offering fundamental insights into the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of optic atrophy, this session aims to enhance clinicians' recognition and understanding, ultimately improving patient outcomes and potentially saving lives through early intervention.

Objectives:

Identify the varied etiologies linked to optic atrophy, encompassing conditions such as glaucoma, ischemic optic neuropathy, demyelinating disorders, hereditary optic neuropathies, compressive lesions, and toxic or nutritional deficiencies.

Differentiate between optic atrophy and other optic nerve–related conditions, distinguishing it from conditions like optic neuritis, papilledema, retinal diseases, and nonorganic visual loss through careful clinical assessment and ancillary testing.

Implement comprehensive treatment strategies addressing the specific causative factors, utilizing pharmacological therapies, neuroprotective agents, antiinflammatory medications, or surgical interventions when indicated.

Implement prompt and appropriate referrals to specialized ophthalmologists, neurologists, or multidisciplinary teams based on the suspected underlying etiology of optic atrophy or associated systemic conditions.

Introduction

Optic atrophy is a pathological term referring to optic nerve shrinkage caused by the degeneration of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons. The term "optic atrophy" is a misnomer since atrophy implies disuse. Therefore, a better term for optic atrophy is "optic neuropathy." However, this term is also controversial since, in certain situations (eg, primary optic atrophy or traumatic brain injury), optic neuropathy may not occur.[1]

Optic atrophy is the end stage of a disease process affecting the retinogeniculate portion of the visual pathway, characterized by a nonspecific sign of optic disc pallor. Although the peripheral nervous system has an intrinsic ability for repair and regeneration, the central nervous system, for the most part, is incapable of such processes. The optic nerve axons are heavily myelinated by oligodendrocytes and reactive astrocytes, which express many inhibitory factors for axonal regeneration.[2] Thus, with its 1.2 million fibers, the optic nerve behaves more like a white matter tract rather than an actual peripheral nerve. The optic nerve head is supplied by pial capillaries that undergo degeneration, contributing to the pallor of the optic disc seen in optic atrophy. This neurovascular degeneration forms the foundation for the development of optic atrophy.

When light is thrown on the fundus from a light source, it undergoes total internal reflection through the axonal fibers. Subsequently, reflection from the capillaries on the disc surface gives rise to the characteristic yellow-pink color of a healthy optic disc. In eyes with cataracts, the red color is exaggerated, giving rise to a hyperemic appearance of the disc. Conversely, the disc may appear to have some degree of pallor in pseudophakic individuals.

Usually, 4-6 weeks are required following axonal damage for the optic disc pallor to start developing. In severe cases, the disc ultimately becomes chalky white. The overlying axons and capillaries degenerate, making the white lamina cribrosa visible. This contrasts sharply with the surrounding red-colored retina. The exact mechanisms responsible for the optic disc pallor seen in optic atrophy are not clearly elucidated. It is assumed that the loss of axonal fibers and the rearrangement of astrocytes contribute to disc pallor. Cogan and Walsh, as well as Hoyt, have mentioned optic disc pallor due to the loss of smaller blood vessels and the variable amount of reactive gliosis and fibrosis as the optic nerve shrinks due to various factors. The degenerated axons also lose the optical property of total internal reflection, leading to the pale optic disc seen in this condition.[3]

Recognition of optic atrophy might prove to be life-saving for the patient. Therefore, it is imperative to have adequate knowledge regarding this fairly common condition. This review presents the basic concepts of optic atrophy.

Etiology

The risk factors for the development of optic atrophy have been denoted by the mnemonic: VIN DITTCH MD. This mnemonic denotes the following conditions:

- V: Vascular

- I: Inflammatory and infectious

- N: Neoplastic or compressive

- D: Primary demyelinating disease or idiopathic optic neuritis

- T: Toxic

- T: Traumatic

- C: Congenital

- H: Hereditary

- M: Metabolic and endocrine causes

- D: Degenerative [4]

A retrospective case series of nonglaucomatous optic atrophy in Malaysia found the main etiologies to be space-occupying intracranial lesions (26%), congenital or hereditary diseases (13%), hydrocephalus (12%), trauma (12%) and vascular causes (12%).

Various conditions in which optic atrophy may occur include:

- Congenital optic neuropathies:

- Isolated conditions include dominant and recessive optic atrophy, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, and Behr’s hereditary optic atrophy.

- Optic atrophy associated with systemic disease or neurological conditions

- Extrinsic compression: Pituitary adenoma, intracranial meningioma, aneurysms, craniopharyngioma, mucoceles, papillomas, metastasis

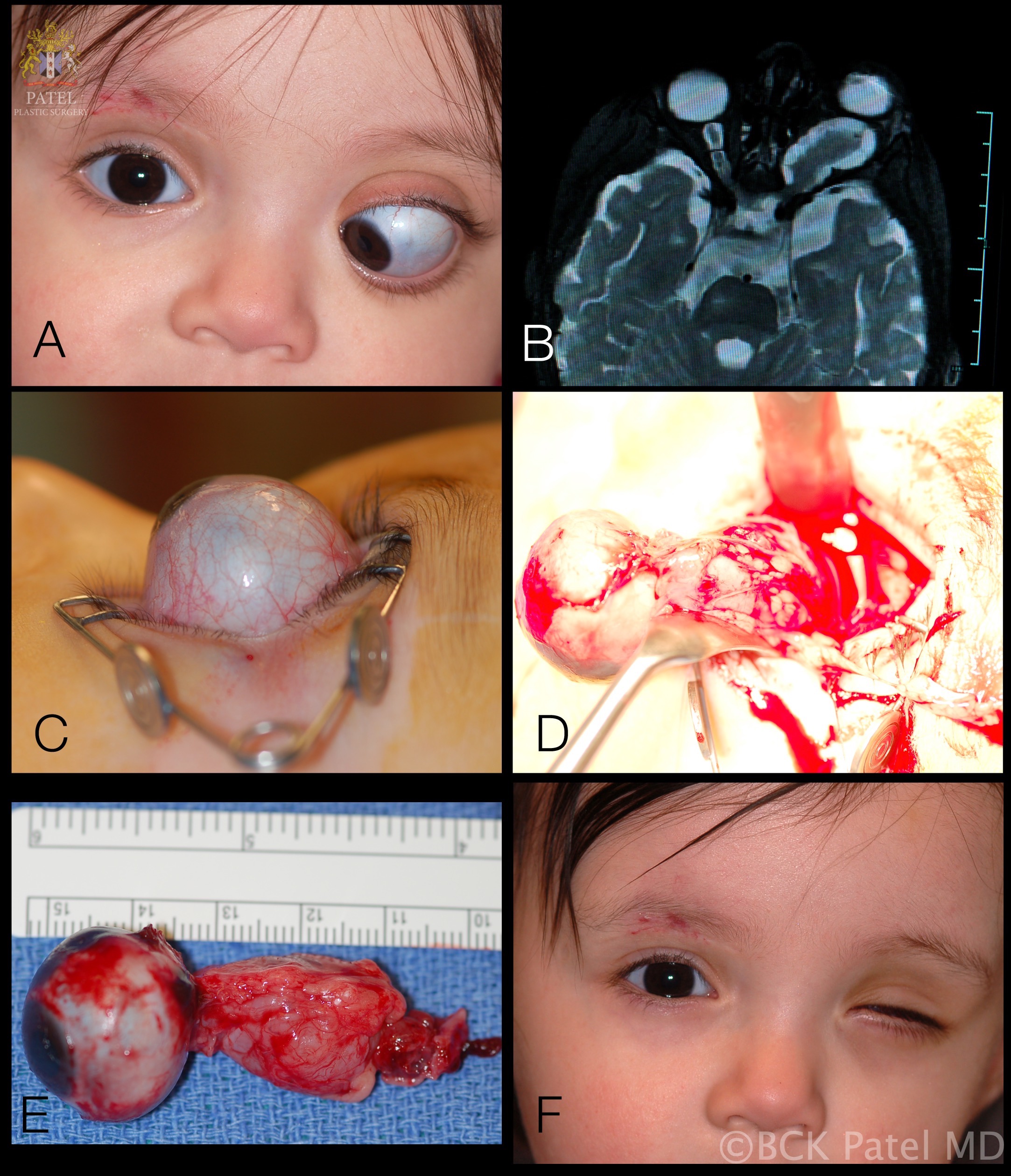

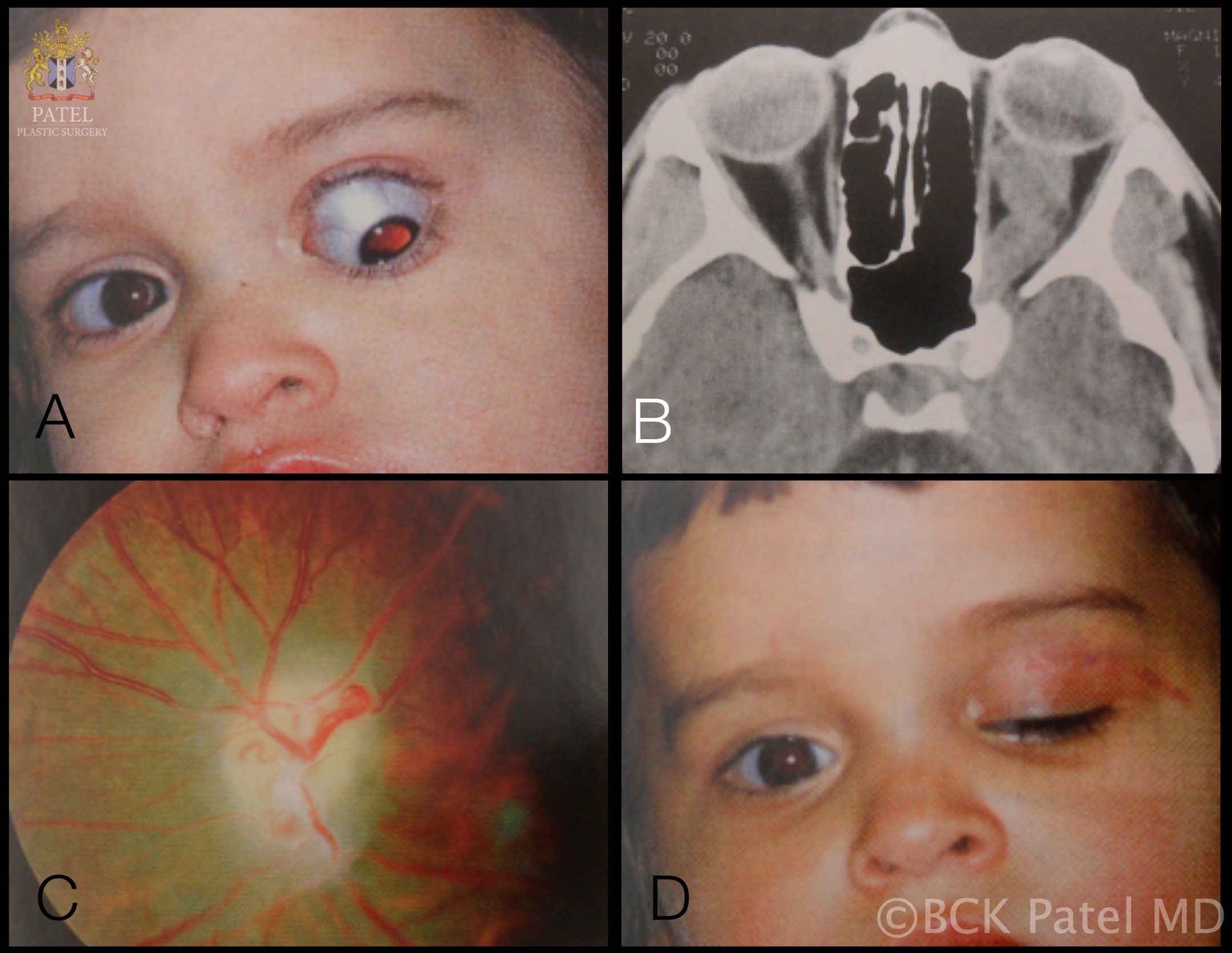

- Intrinsic optic nerve tumors: Optic nerve glioma, optic nerve sheath meningioma, and lymphoma

- Vascular disease: Arteritic and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy [AION], nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy [NAION], central retinal artery occlusion, carotid artery occlusion, cranial arteritis

- Inflammatory disease: Demyelinating optic neuritis (multiple sclerosis, Devic’s disease), sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarthritis nodosa, Churg-Strauss syndrome, meningitis, orbital cellulitis

- Infection: Syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, Aspergillosis, Cryptococcus, chickenpox, measles, mumps

- Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathies: Nutritional amblyopia, toxic amblyopia, thyroid ophthalmopathy, juvenile diabetes, tobacco, methyl alcohol, and drug addiction; optic atrophy due to toxic or nutritional causes is usually symmetrical and insidious in onset.

- Trauma: Trauma to the optic nerve, optic nerve sheath hematoma, damage due to orbital fracture or foreign body

- Swollen optic nerve: Papilledema, AION

- Retinal disease: Retinitis pigmentosa, macular dystrophies

Epidemiology

The prevalence of optic atrophy varies widely. Optic atrophy was one of the five main causes of blindness in prevalence studies from Israel, Japan, Scotland, Zaire, and other countries.[5][6][7][8][9]. In the Oman eye study, 5% of the blindness was attributable to this condition.[10] In a study from Egypt, the age-adjusted blindness prevalence rates per 1000 persons showed that in an urban population, 4.1% of the blindness and in a rural population 1.2% of the blindness was attributable to optic atrophy.[11]

In southern Germany, newly registered blindness-allowance recipients were analyzed for the causes of blindness. Among the 3531 individuals, the standardized incidence rate per 100,000 person-years for optic atrophy was 2.86 (SD 2.66-3.05).[12] In a study from the Baltimore area of the United States, the prevalence of blindness due to optic atrophy in Whites was found to be zero, whereas it was 1.9% in African-Americans, giving a total prevalence of 0.8% across both groups.[13] In another population-based study from the United States, 0.83% of individuals were found to be bilaterally blind. Of these, optic atrophy was responsible for bilateral blindness in 3 persons.[14]

Pathophysiology

The optic nerve head represents the distal portion of the optic nerve. It is the point where axons of the RGCs exit out of the eyeball. The arterial supply to this segment of the optic nerve is through a capillary net originating from the retinal arterioles. Due to the presence of the capillary network and total internal reflection of light in the axons, the optic nerve head appears yellow-pink. The degeneration of RGCs, axons, and capillaries leads to the appearance of the pale optic disc seen in optic atrophy.

Histopathology

In optic atrophy, certain histopathological changes can be seen. These include the widening of the pial septa and subarachnoid space with a redundancy of the dura. In case of trauma, the anterior severed ends of the nerve show bulbous swellings known as Cajal end bulbs.

History and Physical

Patients who develop optic atrophy often complain of loss of vision with the segmental or diffuse blurring of the visual field. History should be directed to the suspected cause of visual impairment. Important points in history include the nature of the presenting illness; visual and ocular history; family, medical, and surgical history; medication and social history; and hospital or institutional admission history. History of diabetes, thyroid disorders, dietary disturbances, alcohol use, tobacco use, recreational drug use, trauma, infections, and systemic diseases should be elicited.

Optic neuritis is an important cause of optic atrophy. It usually occurs in individuals between 10 and 50 years of age. Patients typically present with sudden, usually severe visual loss associated with pain durring ocular movements. AION occurs in individuals above 50 years of age with headache and tenderness of the temporal artery. There is an insidious history of slowly progressive visual impairment in optic atrophy due to tumors. However, hemorrhage within or due to the tumor eroding surrounding vessels would cause a sudden visual loss. Reduced color saturation or contrast sensitivity may develop before the occurrence of defective vision. Red color desaturation is seen in optic neuritis. Although defects in identifying blue-yellow color may be an early sign of dominant optic atrophy, the normal linear association between stereoacuity and Snellen visual acuity could also be lost in optic atrophy.

On examining a case of optic atrophy, the observer may notice reduced visual acuity and contrast sensitivity, as well as the presence of a relative afferent pupillary defect (unless the condition is bilateral). Ophthalmoscopic findings vary from a chalky white disc in advanced cases to subtler changes in milder forms. In the latter case, the color of the optic disc in the fellow eye can be compared. Also, the surface capillary net can be examined with high magnification. In optic atrophy, the net is thin or absent, depending upon the stage of the disease. Another early finding, which may occur even before the development of optic disc color changes, is the loss of peripapillary retinal striations. These changes appear first in the superior or inferior arcades, as dark bands, called "rake defects," due to their resemblance to marks in the soil made from rakes.

Optic atrophy can be classified using different parameters. These parameters can be clinical, pathological, and based upon the extent and etiology.[15]

Clinical Types

Primary optic atrophy

Primary optic atrophy occurs without any preceding swelling of the optic nerve head. The condition is caused by lesions in the anterior visual system extending from the RGCs to the lateral geniculate body (LGB). The etiology of primary optic atrophy varies from conditions such as compressive, hereditary, traumatic, toxic, nutritional, and inflammatory optic neuropathies. In this condition, the axons degenerate in an orderly manner. Subsequently, the resolution is characterized by the laying down of columns of glial cells.

As mentioned earlier, in primary optic atrophy, there is an orderly degeneration of the nerve fibers. The architecture of the optic nerve head is maintained, and the disc appears pale and chalky-white due to cupping and visibility of the lamina cribrosa. Margins of the disc are sharply defined, parapapillary blood vessels attenuated, and the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinned out. There is a loss of the overlying capillary net, a clinical feature known as Kestenbaum sign. Normally, the number of capillaries visible on the optic nerve head is 10. However, in optic atrophy, the counts may reduce to 6.

Secondary optic atrophy

Secondary optic atrophy follows optic disc swelling, such as that seen in papilledema, optic neuritis, or AION. The fibers of the optic nerve exhibit marked degeneration and profuse glial tissue proliferation. The optic nerve head architecture is lost, and disc margins become indistinct. The color of the disc is grey. In this condition, the lamina cribrosa is not visible due to the filling of the cup by overlying proliferative fibroglial tissue. Hyaline bodies (corpora amylacea) or drusen may occur. Peripapillary sheathing of arteries, tortuous veins, and optociliary shunt vessels may be observed. Peripapillary retinochoroidal folds known as Paton Lines, especially temporal to the disc, may be present. Functional tests demonstrate progressive contraction of visual fields in these cases.

Consecutive optic atrophy

Consecutive optic atrophy is associated with diseases that affect the inner retina or its blood supply. Some of those conditions include retinitis pigmentosa, pathological myopia, following pan-retinal photocoagulation, extensive retinochoroiditis, and central retinal artery occlusion. In this type of optic atrophy, the optic nerve head is waxy pale with a normal disc margin, marked attenuation of arteries, and a normal physiologic cup. Clinical features of predisposing retino-choroidal conditions provide a clue to this type of optic atrophy.

Glaucomatous optic atrophy

Glaucomatous optic atrophy is a completely distinct entity. It is characterized by certain specific mechanical and vascular changes in the optic disc, such as an increase in the cup-to-disc ratio and changes in the blood vessels as well as thinning of surrounding RNFL. This type of optic atrophy will not be considered further in this article.

Pathological Types

Ascending optic atrophy

Also known as Wallerian degeneration, this anterograde degeneration occurs as a consequence of injury to the retinal elements or optic nerve head axons. The subsequent degeneration ascends towards the LGB and superior colliculus.[2]

Descending optic atrophy

Also referred to as retrograde optic atrophy, this condition follows a higher-order lesion leading to neuronal death upstream in the pathway. Occipital lesions have been reported to cause bilateral optic atrophy. However, lesions beyond the LGB are unlikely to cause optic atrophy, since the second-order neurons (RGC axons) synapse in the LGB. More commonly, tumors involving the retrobulbar segments of the optic nerve or the chiasm may cause secondary optic atrophy of the descending type.

Types Based on Extent of Neural Loss

Partial optic atrophy

Partial optic atrophy occurs when there is some preservation of neural elements, and the disc may show only mild changes. Visual acuity may range from moderate visual loss to counting fingers. Visual field analysis usually shows concentric contraction with tubular vision. In such cases, only the temporal side of the disc could be pale and known as temporal pallor. This appearance of the disc indicates atrophy of the papillomacular fibers. It can be seen in traumatic or nutritional optic atrophy and multiple sclerosis patients following optic neuritis.

In retrobulbar optic neuritis, the optic disc appearance is normal. In suspicious cases, the disc appearance should not be regarded as normal temporal pallor seen in some healthy discs and investigations should be performed to rule out any pathology. Another phenomenon is band atrophy or bow-tie atrophy. It is characterized by butterfly-shaped nasal as well as temporal optic disc atrophy. It is seen in lesions of the optic chiasm or optic tract.[16]

Total optic atrophy

Total optic atrophy is characterized by the complete loss of the nerve fibers in the optic nerve. In such cases, the optic disc is completely pale, and vision is usually no light perception.

Evaluation

In the case of optic atrophy, a number of investigations can be tailored according to the suspected etiology of the condition.

Visual Field Tests

These should be performed whenever possible to help in diagnosis as well as follow-up of the patient’s condition. The 30-2 program is most useful in the investigation of optic atrophy. Visual field changes can include enlargement of the blind spot and paracentral scotoma, altitudinal defects (as seen in AION and optic neuritis), and bitemporal defects (seen in compressive lesions, similar to optic chiasma tumors).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with contrast is useful in the diagnosis and should be ordered in all patients with optic atrophy, if possible. Imaging techniques may demonstrate space-occupying lesions, sinusitis, hyperpneumatized sinuses, fibrous dysplasia, and fractures.

On MRI images, multiple sclerosis plaques are typically seen located in the infratentorial region, in the deep white matter, periventricular, juxtacortical, or mixed white matter-grey matter lesions. The lesions appear iso- or hypointense on T1 images (T1 black holes), whereas on T2 images, they are hyperintense. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence also shows hyperintense lesions. Other sequences, such as T1-weighted post-contrast (gadolinium), MR spectroscopy, and double-inversion recovery (DIR), can also be used.

Computed Tomography Scan

In suspected fractures, a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan is preferable.

Optical Coherence Tomography

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be performed to demonstrate the thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography (B-scan) is recommended for orbital tumors. B-scan in papilledema may demonstrate nerve sheath dilatation.

Blood Glucose Level

Testing blood glucose is useful for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, as well as collecting a baseline level before initiating steroid therapy.

Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Examination

These can be used to look for vascular causes of optic atrophy.

Carotid Doppler Ultrasound Study

Carotid occlusion may need to be ruled out in selected cases.

Vitamin B-12 Levels

Nutritional causes of optic atrophy need to be ruled out when suggestive. However, a nutritional etiology may be obvious from history and systemic examination.

Laboratory Tests

These may be required when indicated; investigations include:

- Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL)

- Treponema Pallidum Hemagglutination Assay (TPHA)

- Antinuclear antibody levels

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme assay

- homocysteine levels

- Antiphospholipid antibodies

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for toxoplasmosis, others (syphilis, hepatitis B), rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex (TORCH panel)

Electroretinography (ERG)

Results may show abnormalities such as:

- Subnormal: Potential less than 0.08 µv, seen in toxic neuropathy

- Negative: When a large a-wave is seen, it may be due to giant cell arteritis, central retinal artery occlusion, or central retinal vein occlusion.

- Extinguished: This is the response seen in complete optic atrophy.

Visually Evoked Response/Visually Evoked Potential

In optic neuritis, Visually Evoked Response (VER)/Visually Evoked Potential (VEP) has an increased latency period and decreased amplitude compared with the normal eye. Compressive optic lesions tend to reduce the amplitude of VER/VEP while producing a minimal shift in the latency.

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA)

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) can be performed in cases of retino-choroiditis and diabetic retinopathy to look for areas of capillary drop-out, neovascularization, and other defects. In optic disc drusen, FFA shows fundus autofluorescence.

Treatment / Management

The ideal treatment for optic atrophy would involve neuroregeneration. Unfortunately, such modalities are still not available for clinical use. Pharmacological treatment for optic atrophy has also been largely ineffective. The only focus in management is treating the exact cause before the development of significant damage to salvage useful vision. Once the condition is stabilized, low-vision aids can be tried for select individuals.

Pulse intravenous methylprednisolone has been used in conditions such as optic neuritis, arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and traumatic optic neuropathy with successful outcomes. The optic neuritis treatment trial recommended doses of 500-1000 mg/day of IV methylprednisolone for three days, followed by oral prednisolone 1 mg/Kg of body weight for 11 days. Beta-interferons and glatiramer acetate have been used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis and related optic neuritis to reduce the occurrence of clinical lesions seen on MRI as well as the number of recurrences.[17][18]

Stem cell treatment may prove to be key in the future treatment of neuronal disorders. Neural progenitor cells can be delivered to the vitreous from where they can integrate into the ganglion cell layer of the retina. These cells would turn on neurofilament genes, and migrate into the host optic nerve to stimulate the regeneration of neural elements.[19]

Differential Diagnosis

Certain conditions may mimic optic atrophy and have to be ruled out, including:

Optic Nerve Pit

These are congenital anomalies characterized by a greyish round or oval depression, usually on the temporal aspect of the optic nerve head. Serous macular detachments develop in nearly half of the cases.

Myelinated Nerve Fibers

Optic nerve myelination usually stops at the level of the lamina cribrosa. However, myelination extends into the retina following the nerve fiber bundles in certain individuals. Clinically they appear as feathery white patches that may obscure the disc margin and vessels. Visual field examination will show the enlargement of the blind spot.

Optic Disc Drusen

These are usually calcific deposits within the substance of the optic nerve head. They are bilateral in around 75% of the individuals. Usually asymptomatic, they may present with the occasional blurring of vision. In the pediatric age group, drusen are buried within the disc and appear as pseudo-papilledema. In adult life, they get exposed, enlarge, and calcify. Later they may regress, leaving a pale disc. There is the filling of the optic cup, anomalous branching vasculature emanating from the central core, and hyaline bodies on the surface. Drusen also demonstrate fundus autofluorescence.

Optic Nerve Hypoplasia

This is a common optic nerve anomaly. The disc appears notably small due to the lack of axons passing through the optic nerve head.

Brighter-Than-Normal Luminosity

Using excessive illumination from the ophthalmoscope or slit lamp causes the disc to appear pale.

Prognosis

The visual prognosis in optic atrophy depends upon the extent of axonal loss. In partial optic atrophy, the visual impairment would be mild to moderate. There may even be no decrease in measured visual acuity but only a decrease in visual field. However, in total optic atrophy, the prognosis is poor. Early and intensive treatment in conditions such as optic neuritis, and toxic or nutritional optic neuropathy, may lead to nearly complete recovery.

Complications

Optic atrophy is not a disease per se; it is a sign indicating several conditions. Therefore, the complications are related to the underlying disease, rather than the optic atrophy itself. The direct complication of optic atrophy is vision loss.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the vision is stable, rehabilitative measures can be undertaken in the form of low-vison aids, change in the work environment, occupational rehabilitation, and avoidance of causative factors, which may cause progressive visual deterioration.

Consultations

Since the cause of optic atrophy is often systemic, relevant consultations should be done. When required, multidisciplinary assessments such as neurology, neurosurgery, and infectious disease can be performed.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The need to maintain a healthy lifestyle should be emphasized to the public. Dietary disturbances and addictions can often lead to optic atrophy and are avoidable. The general public, especially the vulnerable groups, should be educated regarding this aspect. Symptoms of systemic conditions that may indicate the development of optic nerve damage should be explained to patients with those diseases.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As optic atrophy is not a disease but a sign of some other condition, it requires interprofessional communication and a multidisciplinary approach to this problem. The disease outcome can be enhanced by interacting with physicians to manage conditions such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis and with surgeons when dealing with tumors and space-occupying lesions. Dieticians have to be involved in cases of nutritional anomalies. Optometrists have to play a role in providing visual care and rehabilitation. Similarly, the role of nurses in patient care when individuals have bilateral visual loss or have restricted activities from systemic disease is also of prime importance. Occupational rehabilitation involves employers and social service providers. Overall, efforts should be made to improve the quality of life of the affected individuals.[20]