Continuing Education Activity

Syphilis is caused by infection by the spirochete, Treponema pallidum. Ocular manifestations can occur at any stage of the disease with varied clinical presentations. Syphilis can involve almost any ocular structure, but posterior uveitis and panuveitis are the most common presentations. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of ocular syphilis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Outline the etiology of ocular syphilis.

- Explain the common physical exam findings associated with ocular syphilis.

- Review the management considerations for patients with ocular syphilis.

- Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients affected by ocular syphilis.

Introduction

Syphilis was initially called the "French disease" by the people of Naples as they claimed that the disease was spread by French troops during the French invasion in the late 15th century. The disease acquired its current name, syphilis, from the title character of a poem written by Italian physician and poet Girolamo Fracastoro, describing the havoc of the disease in his country in 1530.[1] The disease is most commonly transmitted sexually, and its clinical course is divided into primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary syphilis. Transplacental spread leads to congenital syphilis. Ocular manifestations can occur at any stage of the disease with varied clinical presentations because of which the disease is also known as the great imitator, as it can mimic a number of ocular diseases.

Syphilis can involve almost any ocular structure, but posterior uveitis and panuveitis are the most common presentations. Other common manifestations include interstitial keratitis, recurrent anterior uveitis, retinal vasculitis, and optic neuropathy.[2] Ocular syphilis, if untreated, may lead to blindness. Ocular manifestations can be associated with neurosyphilis. Diagnosis is based on clinical exam with serological tests. The disease can be treated effectively with appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Etiology

Syphilis is caused by infection with the spirochete, Treponema pallidum. Spirochetes are a phylum of bacteria that are characterized by long and helically coiled cells having flagella which provide them motility. It was first isolated from skin lesions of patients with syphilis in 1905 by Schaudin and Hoffman.[3] T. pallidum is approximately 0.01 to 0.02 microns wide and 5 to 20 microns long and is almost invisible under direct microscopy but can be detected by darkfield microscopy.

Epidemiology

The origin of syphilis has been debated for centuries. There are two hypotheses: the first one hypothesizes that syphilis was carried to Europe from America by the crew of famous sailor Christopher Columbus while the second one proposes that the disease existed in Europe since the Hippocratic era but was often misdiagnosed and went unrecognized. These two theories are referred to as the "Columbian" and "pre-Columbian" hypotheses of the origin of syphilis.[4]

The first documentation of an outbreak of syphilis occurred in the late 15th century in Italy. Syphilis continued to spread and was rampant in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries. The disease, however, declined rapidly during the early and mid-20th century with the widespread use of antibiotics. Since early 2000, rates of syphilis have been increasing in the U.S., Australia, and Europe, primarily among men who have sex with men.[5]

In the U.S., approximately 55,400 people are infected newly each year. It was estimated that in 2018, men accounted for approximately 86% of all cases of syphilis in the U.S.[6] Syphilis is also common in patients co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The disease is often difficult to diagnose and has more serious effects in patients with AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

Pathophysiology

Humans are the only hosts of the organism, and there is no animal reservoir of Treponema pallidum, so the disease only spreads via human to human transmission. Initial infection with the spirochete evokes both a humoral and cellular immune response in the body. Its limited outer membrane polysaccharides and few surface proteins make it difficult for the immune system to identify and fight the infection quickly. Its incubation period is long, about 4 weeks to three months. The infection leads to the formation of an erythematous papule at the inoculation site, and later the lesion erodes to form a painless ulcer. These lesions are often associated with local lymphadenopathy, which may be tender. Hematogenous spread from the primary site then leads to the involvement of multiple organs, including eyes.

The disease is highly infectious in patients with primary, secondary syphilis or early latent syphilis with mucocutaneous involvement. Late latent syphilis and tertiary syphilis are considered to be non-infectious stages of the disease. The transplacental spread of the spirochete leads to congenital syphilis.[7] Syphilis in pregnancy, if left untreated, tends to have a severe impact on fetal development. It can lead to bone deformities, neurologic impairment, deafness, ocular syphilis, and even neonatal death.

History and Physical

The natural history of acquired untreated syphilis has been divided into four stages: primary syphilis, secondary syphilis, latent syphilis, and tertiary syphilis. Ocular manifestations can occur at any stage of the disease with varied presentations.

In clinical practice, it is important to note that many patients who present with ocular signs of syphilis do not necessarily have the systemic signs of syphilis. The ocular symptoms in secondary syphilis occur as late as 6 months after the initial infection when many of the systemic manifestations have already resolved. Nearly 50 percent of patients with ocular manifestations in tertiary syphilis have associated systemic signs of the disease.[8] Hence, the importance of detailed history taking cannot be understated while examining a patient suspected of having ocular manifestations of syphilis. In general, acute inflammatory presentations like episcleritis, iridocyclitis, and retinitis are more commonly associated with secondary syphilis, while chronic gummatous or granulomatous inflammation of the ocular structures is classical of tertiary syphilis, although there is a significant overlap.

The common presentations at different stages are discussed below.

Primary Syphilis

As mentioned earlier, lesions of primary syphilis occur due to the direct inoculation of T. pallidum at the local site. Ocular manifestations of primary syphilis are limited to chancres of the eyelid and the conjunctiva due to direct contact with secretions or from contaminated fingers.[9] Although extremely rare, a primary syphilitic lesion in the lacrimal gland has been reported.

Secondary Syphilis

If untreated, primary syphilis progresses to secondary syphilis in 4 to 10 weeks. A generalized maculopapular or pustular rash is characteristic of secondary syphilis and may involve palms of the hands, soles of the feet, and/or trunk. The rash may involve the eyelids and can lead to blepharitis and madarosis. Conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis, iridocyclitis with or without iris nodules have all been reported in secondary syphilis.[10][11][12]

- Anterior uveitis is usually unilateral, to begin with, and can be either granulomatous or non-granulomatous type. Iris roseolae are relatively specific for syphilis but are rarely observed. They are described as dilated vascular tufts in the middle third of the iris surface and are easily identified on slit-lamp biomicroscopy.[13] Syphilitic anterior uveitis is often associated with raised intraocular pressure and is one of the important causes of so-called inflammatory ocular hypertension syndrome.[14]

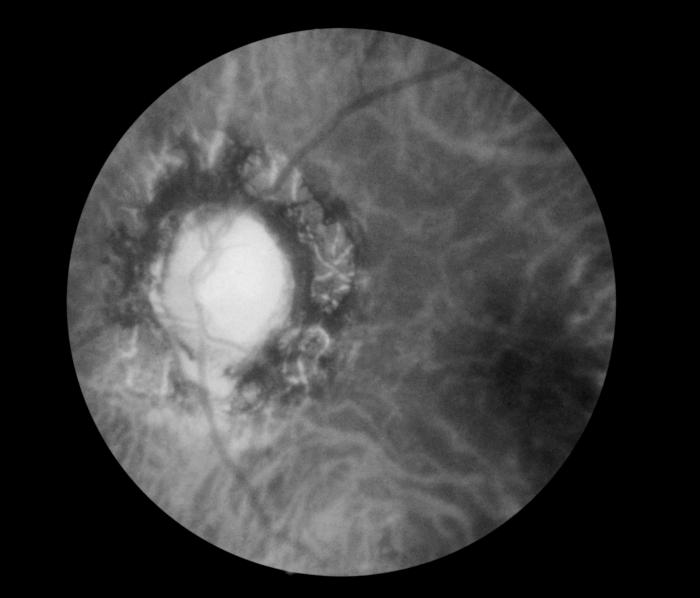

- Posterior segment involvement usually occurs in late secondary syphilis. Vitritis, necrotizing retinitis, chorioretinitis, retinal vasculitis, and optic neuritis have been reported to occur in secondary syphilis.[15] Chorioretinitis is the most common presentation and is typically multifocal, often with a shallow serous retinal detachment and significant vitritis.[16] Fluorescein angiography shows a pattern of early hypofluorescence followed by late staining of the lesions. Multifocal lesions can coalesce to become confluent and mimic acute retinal necrosis (ARN).[17][18] However, careful examination of the lesions may provide clues to the diagnosis of syphilitic retinal necrosis (SRN). In ARN, the lesions typically start in the periphery, whereas in SRN, the lesions often start from the posterior pole. Furthermore, in SRN, the surface of the lesion often appears to have a layer of exudative membrane obscuring the underlying retina.[19] The retinal necrotic tissue appears homogeneous in ARN, whereas the areas of necrosis have a mottled appearance in SRN. Multiple small round white ball-like vitreous opacities are very common in syphilitic posterior uveitis.

- Acute posterior placoid chorioretinopathy (APPC) is a characteristic lesion of syphilis and is frequently seen in patients with secondary and late latent syphilis. It presents as one or more yellowish placoid like retinochoroidal lesions that are typically located in the macular region. The margin of the lesion is usually round and more prominent. This lesion was originally described by Donald Gass and may result from an infection with T. pallidum of the RPE layer in the posterior pole. However, many believe that the lesion occurs as a consequence of indirect immune-mediated hypersensitivity.[20] SD-OCT findings of the lesion include disruption of the inner segment/outer segment junction, nodular thickening of the RPE, subretinal fluid, and punctate hyperreflectivity of the choroid.[21] Isolated retinal vasculitis can affect arteries, veins, or both and can be occlusive. Retinal vasculitis is often associated with a "ground glass" retinitis, which is characteristic of syphilis.[22] Typically, arteries are more involved.

- Acute meningitis is reported in 1% to 2% of patients with secondary syphilis, which can cause increased intracranial pressure, and the patient may present with papilledema. Other neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of secondary syphilis include optic neuritis, optic neuropathy, and Argyll Robertson pupil.[23]

Tertiary Syphilis: The gumma is a chronic granulomatous lesion that heals with scarring and is a typical lesion of tertiary syphilis. Gummas commonly develop in the skin and can involve the eyelids. Gummatous dacryoadenitis have also been reported.[24] Bilateral diffuse periostitis is the most common orbital finding of tertiary syphilis. Other ocular manifestations of tertiary syphilis include blepharitis with madarosis, keratitis, iridocyclitis, vasculitis, chorioretinitis, venous, and arterial occlusive disease, retinal detachment with choroidal effusion, macular edema, optic neuritis, neuroretinitis, pars planitis, and pseudo-retinitis pigmentosa. Argyll Robertson pupils and optic atrophy are frequent in neurosyphilis.[18][25]

Congenital syphilis: The most common manifestation of congenital syphilis is bilateral interstitial keratitis. Pigmentary retinitis and secondary glaucoma can also occur as a result of congenital syphilitic keratouveitis.[26] Hutchinson's triad of congenital syphilis consists of interstitial keratitis, Hutchinson teeth (notched incisors), and deafness (sensorineural).

Evaluation

A complete ophthalmic examination including pupillary examination, visual acuity, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, applanation tonometry, fundus biomicroscopy, should be performed in all cases suspected to have syphilis. Case-specific investigations include fundus photo, autofluorescence, fluorescein angiography, optical coherence tomography, and indocyanine green angiography. Laboratory tests for syphilis include darkfield microscopy and the serological tests for syphilis.

Darkfield microscopy is used to identify spirochetes from tissue fluids. However, the examination requires expertise as it is difficult to distinguish from T. pallidum from other spirochetes.

The serological tests are classified as treponemal and non-treponemal. Venereal disease research laboratories (VDRL) test and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test are two most commonly used non-treponemal tests for syphilis. Infection with spirochete stimulates the production of nonspecific antibodies against cardiolipin. Both VDRL and RPR tests are assays for detecting anticardiolipin antibody. The sensitivity and the specificity of the non-treponemal tests vary depending on the stage of the disease. The VDRL test becomes positive approximately 1 to 2 weeks after the surfacing of the primary chancre and is positive in up to 99% of patients presenting with secondary syphilis. However, in later stages of the disease, the VDRL test sensitivity decreases, and only about 70% of patients with tertiary syphilis have a positive test result. The serological tests become nonreactive after treatment, and the VDRL test is commonly used to monitor treatment response.

The treponemal tests are highly specific for T. pallidum and include enzyme immunoassay (EIA), T. pallidum hemagglutination tests (TPHA), and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS). The treponemal tests stay positive throughout life. Any weakly reactive or reactive VDRL/RPR test needs to be confirmed with these tests. The FTA-ABS test is highly specific for syphilis, but false-positive results can be seen in patients with various diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, biliary cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, infectious disease like hepatitis, HIV infection, infectious mononucleosis, rickettsial disease, scarlet fever, and also in pregnant females.[27]

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be used in the near future to detect T. pallidum in ocular specimens.

To increase the sensitivity and specificity of the serological diagnosis of syphilis, both non-treponemal and treponemal tests must be performed, and the results should be interpreted taking into account the history of prior syphilis exposure and any previous treatment for syphilis. The CDC recommends the following serologic testing algorithms:

- Traditional syphilis screening algorithm: A nontreponemal test (VDRL/RPR) is used as the initial screening test with reactive samples undergoing a second confirmatory treponemal test, such as the FTA-ABS, TPPA, or EIA.

- Reverse-sequence syphilis screening algorithm: A treponema-specific immunoassay, such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (EIA) or chemiluminescent immunoassay (CIA) is used for initial screening of the disease. Samples that are reactive then undergo a non-treponemal titer like VDRL/RPR. A second treponemal test (like FTA-ABS) is performed if the non-treponemal test is nonreactive for confirmation of the disease.

Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis for VDRL and FTA-ABS is indicated in all patients diagnosed with ocular syphilis to rule out neurosyphilis as the treatment strategy in such patients with central nervous system (CNS) involvement is different from that for patients without CNS involvement.

All patients diagnosed with syphilis should also be screened for HIV infection, as both are sexually transmitted diseases with similar risk factors. Recognition of HIV coinfection is important because the clinical presentation may be atypical, and the therapeutic approach to syphilis may differ in such patients.[28]

Treatment / Management

Although the mainstay of treatment is systemic antibiotics, topically administered drugs are useful in alleviating acute ocular symptoms. Topical steroids, NSAIDs, mydriatics like atropine and lubricating agents are all helpful and can be used as indicated by the ophthalmologist.

Systemic therapy is administered according to the stage of the disease. Patients with ocular syphilis are treated as neurosyphilis.

The following are treatment protocols recommended by the center for disease control and prevention (CDC):

- Primary and secondary syphilis is treated with a single dose of intramuscular (IM) penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million units, or procaine penicillin, 2.4 million units IM daily, and probenecid, 1 g orally 4 times a day for 14 days. In patients who are allergic to penicillin, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days or ceftriaxone 1 to 2 gm IM or intravenously (IV) daily for 10 to 14 days or tetracycline 100 mg orally 4 times daily for 14 days, can be used. Azithromycin has also been used.[29][30]

- Latent and tertiary syphilis, including neurosyphilis, is treated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 3 to 4 million units IV every 4 hourly for 10 to 14 days, or benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM weekly for 3 weeks. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin also have been used in patients allergic to penicillin.[31]

Penicillin is the only antibiotic with documented efficacy for treating syphilis in pregnant patients. Pregnant females with syphilis who report penicillin allergy should be desensitized first and then treated with penicillin G.

Oral steroids, along with supplements, are often required to control ocular inflammation along with antibiotic therapy. The use of intravitreal dexamethasone implant for refractory macular edema in syphilitic uveitis has also been reported.[32] However, steroids should not be started before starting antibiotics, in which case, the disease may worsen, becoming life-threatening or sight-threatening.[33]

Patients treated for syphilis should have the VDRL test repeated every three months for a period of 1-year post-treatment as titers should become nonreactive within a year after therapy. Patients should be retreated, if an initially high-titer VDRL test does not decrease fourfold within a year, or if a previously nonreactive VDRL test becomes reactive again.

Differential Diagnosis

Syphilis can mimic almost any of the ocular diseases; hence syphilis is included in the differential diagnosis of almost all inflammatory diseases of the eye. The most common differential diagnoses of syphilitic posterior uveitis include

- Intermediate uveitis

- Non-infectious uveitis like sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis

- White dot syndromes

- Macular choroiditis/serpiginous choroidopathy

- Chorioretinitis due to other causes

- Acute retinal necrosis (ARN)

- Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN)

- Other infectious retinitis like toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus retinitis

- Other causes of vasculitis like tuberculosis, Behcet disease

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Patients receiving intravenous therapy should be monitored for a Jarisch– Herxheimer reaction (JHR). A patient with JHR usually presents with fever with sweating, headache, malaise, and an exacerbation of the pre-existing signs and symptoms of syphilis like worsening of rashes or ocular inflammation. It is believed to be a hypersensitivity response due to the release of inflammatory cytokines from the dying organisms. JHR typically peaks in about 8 hours after receiving the first dose of antimicrobial therapy and gradually resolves over 24 hours. Prophylaxis with systemic steroids can prevent the response in some cases.[34]

Prognosis

If the disease is recognized and treated early, most patients recover without long-term sequelae. If untreated, about 25% of patients have one or more relapses in their lifetime. Most of these patients remain in the latent stage; however, about one-third go on to develop tertiary syphilis.

Complications

Long term complications of ocular syphilis include corneal opacity, cataract, glaucoma, epiretinal membrane, macular edema, optic atrophy, chorioretinal scarring, and rarely choroidal neovascularization.[18][35]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The primary care provider and nurse practitioner should educate the patient on preventive measures such as avoiding sexual activity during active disease and adopting safe sex practices like the use of barrier protection. Patients' sexual partners have to be identified and investigated for syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Patients who also have coinfection with HIV need long term treatment and regular follow up. A pregnant patient has to be informed about the chances of vertical transmission and needs regular follow up with obstetrician.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ocular syphilis is difficult to diagnose due to varied presentations of the disease, and misdiagnosis is common. It is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an ophthalmologist, neurologist, cardiologist, dermatologist, infectious disease expert, internist, gynecologist, and specialty-trained ophthalmology nurse. Every member of the team should communicate regularly with each other on the patient’s health issues concerning their department.