Introduction

The ankle joint is a hinged synovial joint that is formed by the articulation of the talus, tibia, and fibula bones. The articular facet of the lateral malleolus (bony prominence on the lower fibula) forms the lateral border of the ankle joint while the articular facet of the medial malleolus (bony prominence on the lower tibia) forms the medial border of the joint. The superior portion of the ankle joint forms from the inferior articular surface of the tibia and the superior margin of the talus. Together, these three borders form the ankle mortise.

The talus articulates inferiorly with the calcaneus and anteriorly with the navicular. The upper surface, called the trochlear surface, is somewhat cylindrical and allows for dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the ankle. The talus is wider anteriorly and more narrow posteriorly. It forms a wedge that fits between the medial and lateral malleoli making dorsiflexion the most stable position for the ankle.

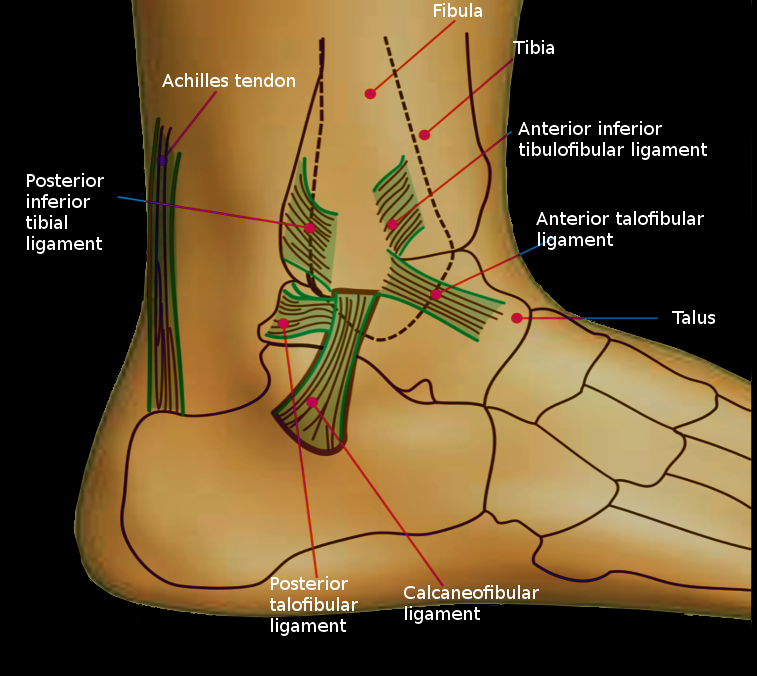

The ankle is stabilized by strong collateral ligaments medially and laterally. The main stabilizing ligament medially is the deltoid ligament, and laterally the ankle has stabilization from three separate ligaments, the anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments, and the calcaneofibular ligament. The anterior and posterior talofibular ligaments connect the talus to the fibula, and the calcaneofibular ligament connects the fibula to the calcaneus inferiorly. The anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) is the weakest of the three lateral ligaments and thus the most frequently injured. The deltoid ligament actually consists of four ligaments that form a triangle connecting the tibia to the navicular, the calcaneus, and the talus. The anterior and posterior tibiotalar ligaments connect the tibia to the talus. The last two ligaments of the triangle are the tibionavicular ligament which attaches to the navicular anteriorly and the tibiocalcaneal ligament which attaches to the calcaneus inferiorly.[1]

Structure and Function

The ankle joint is important during ambulation because it adapts to the surface on which one walks. The movements that occur at the ankle joint are plantarflexion, dorsiflexion, inversion, and eversion. The muscles of the leg divide into anterior, posterior, and lateral compartments. The leg's posterior compartment of the leg divides into the superficial posterior compartment and the deep posterior compartment. The superficial posterior compartment consists of the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscles, which are the primary muscles involved in ankle plantarflexion. The deep compartment contains the tibialis posterior, the flexor digitorum longus, and the flexor hallucis longus muscles. The flexor digitorum longus and the flexor hallucis longus have roles in ankle plantarflexion, and the tibialis posterior muscle plays a role in ankle joint inversion. The tibialis anterior muscle, found in the anterior compartment of the leg, is the primary muscle that facilitates dorsiflexion of the ankle joint. The peroneus longus and peroneus brevis muscles, found in the lateral compartment of the leg, function to facilitate eversion of the ankle joint.[2]

Ligament Testing

The anterior drawer test is used to examine the integrity of the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and utilizes the anterior translation of the talus under the tibia. The test is performed by stabilizing the distal tibia (and fibula) with one hand while the other hand holds the calcaneus and puts the ankle in slight dorsiflexion. The calcaneus is then translated anteriorly while simultaneously translating the leg (distal tibia and fibula) posteriorly. Excessive talar anterior translation on the injured side compared to the uninjured side is indicative of a positive test.

The talar tilt test, also known as the inversion stress test, is used to test the integrity of calcaneofibular ligament. The examiner performs this test by stabilizing the distal tibia (and fibula) with one hand and inverting the ankle while it is in the neutral position. Pain elicited at the area of the ligament indicates a positive test.

The eversion stress test is used to assess for a deltoid ligament injury. It is performed by everting and abducting the heel while stabilizing the tibia (and fibula). Increased laxity or pain indicates a positive test.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The main blood supply to the ankle comes from the anterior tibial artery, the posterior tibial artery, and the peroneal artery.

The anterior tibial artery subdivides into the anterior medial malleolar artery (supplies the medial malleoli), anterior lateral malleolar artery (supplies the lateral malleoli) and the dorsalis pedis artery (supplies the dorsum of the foot).

The posterior tibial artery subdivides into the posterior medial malleolar artery (supplies the medial malleolus) and the medial calcaneal artery (supplies the heel). The terminal branches of the posterior tibial artery are the lateral plantar artery and medial plantar arteries. The larger of the terminal branches is the lateral plantar artery, which completes the deep plantar arch. The deep plantar arch is an arterial anastomosis found on the sole of the foot that is made up of the deep plantar artery (branch of dorsalis pedis) and the lateral plantar artery. The medial plantar artery runs in the medial foot and terminates as the superficial plantar arch (an inconstant anastomosis between the medial and lateral plantar arteries).

The peroneal artery subdivides into the perforating artery, the posterior lateral malleolar artery, and the lateral calcaneal artery. The perforating artery joins with the anterior lateral malleolus artery and supplies the posterior talus. The posterior lateral malleolar artery supplies the lateral malleolus, and the lateral calcaneal artery supplies the heel.[4]

Nerves

Innervation to the lower leg originates from the lumbar plexus and the sacral plexus.

The lumbar plexus gives rise to the femoral nerve, which becomes the saphenous nerve when it reaches the medial side of the knee. The saphenous nerve descends along the medial leg and then divides into two branches (a branch that ends at the ankle and a branch that passes in front of the ankle to the medial side of the foot) and provides sensory innervation to the medial ankle joint and the medial arch of the foot.

The sciatic nerve forms from the sacral plexus, which further branches into the tibial and common fibular nerve.

The tibial nerve travels posterior to the medial malleolus and branches into the medial calcaneal nerve (provides sensory innervation to the heel), medial plantar nerve (provides sensory innervation to the medial two-thirds of the plantar surface of the foot and motor innervation to the muscles on the medial sole), and lateral plantar nerve (provides sensory innervation to the lateral sole and lateral one-third of the plantar surface of the foot and motor innervation to the deep muscles of the foot).

The common fibular nerve travels around the fibular head and subdivides into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves.

The superficial peroneal nerve travels in the lateral compartment of the leg down to supply sensory innervation to the lateral malleolus where it divides into the intermediate dorsal cutaneous nerve (sensory innervation to the dorsal foot) and the medial dorsal cutaneous nerve (sensory innervation to the medial hallux).

The deep peroneal nerve runs in the anterior compartment of the leg along with the anterior tibial artery and passes under the inferior and superior extensor retinaculum. The medial branch supplies sensory innervation to the interdigital space between the first and second toes. The lateral branch supplies motor innervation to the extensor hallucis brevis and the extensor digitorum brevis. The tibial and common fibular nerves also give rise to a medial and lateral sural nerve, respectively, which provides sensory innervation to the lateral heel and foot.[5][6]

Clinical Significance

Ankle Fracture

Ankle fractures are common in all ages with the involvement of one or both malleoli. The fracture pattern determines the stability of the fracture. Patients typically present with pain, swelling, and inability to bear weight on the ankle joint. Management of stable fractures includes a short leg cast for 4 to 6 weeks. Unstable fractures require an open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) to restore a congruent mortise and fibular length.

The Lauge-Hansen and AO classifications are tools used to help determine the prognosis and treatment of ankle fractures. The Lauge-Hansen classification has its basis on the foot position and the mechanism of injury. Fractures classify into four different groups: supination-adduction, supination-external rotation, pronation-abduction, pronation-external rotation. The first term describes the position of the foot during an injury while the second refers to the direction of force applied to the ankle.

The Danis-Weber classification of describing ankle fractures has its basis on the location of the fibular fracture. This classification divides into three groups: fracture below the syndesmosis (type A), at the syndesmosis (type B), and above the syndesmosis (type C).[7][8]

Talus Fracture

This injury usually occurs from a high energy injury like a motor vehicle accident or a fall from a height. The talus has a tenuous blood supply and is at high risk of avascular necrosis (AVN) in displaced fractures. The Hawkins classification helps to predict the chance that AVN will occur. There are four different types of talus fractures, with type I having the best prognosis and type IV predicting a hundred percent chance of developing AVN. Type I is a nondisplaced fracture of the talar neck, type II is a subtalar dislocation. Type III is similar to type II, but with tibiotalar dislocation, type IV is similar to type III but with a talonavicular dislocation. Determining the type of fracture is not only important for predicting the chance of AVN, but it is also important for determining the type of treatment needed. Type I fractures are usually treated with percutaneous pins while types II-IV are treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).[9]

Ottawa Ankle Rules:

Simple guidelines to identify patients with ankle or midfoot injury who do not need X-ray. Ankle X-ray is necessary if any of the following are present.[10]

- Inability to bear weight on the affected ankle

- Bone tenderness along the posterior aspect of the distal 6 cm of either the medial or lateral malleolus

- Point tenderness at the proximal base of the fifth metatarsal

- Point tenderness over the navicular bone