Continuing Education Activity

Spina Bifida is a generalized term for the neurologic condition resulting from the failure of neural tube closure of varying degrees during fetal development. It can lead to significant neurologic dysfunction and can cause functional limitations in adulthood affecting the quality of life. Spina bifida is associated with several complications and sequelae involving various organ systems so it is important to diagnose early and take a multidisciplinary approach to prevent severe morbidity. This activity reviews the prevention, evaluation, and treatment of spina bifida and the importance of interprofessional collaboration to avoid catastrophic outcomes.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of spina bifida and associated conditions and emergencies.

- Recall, analyze, and select appropriate history, physical, and evaluation of spina bifida.

- List the treatment and management options available for spina bifida.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance spina bifida and improve outcomes.

Introduction

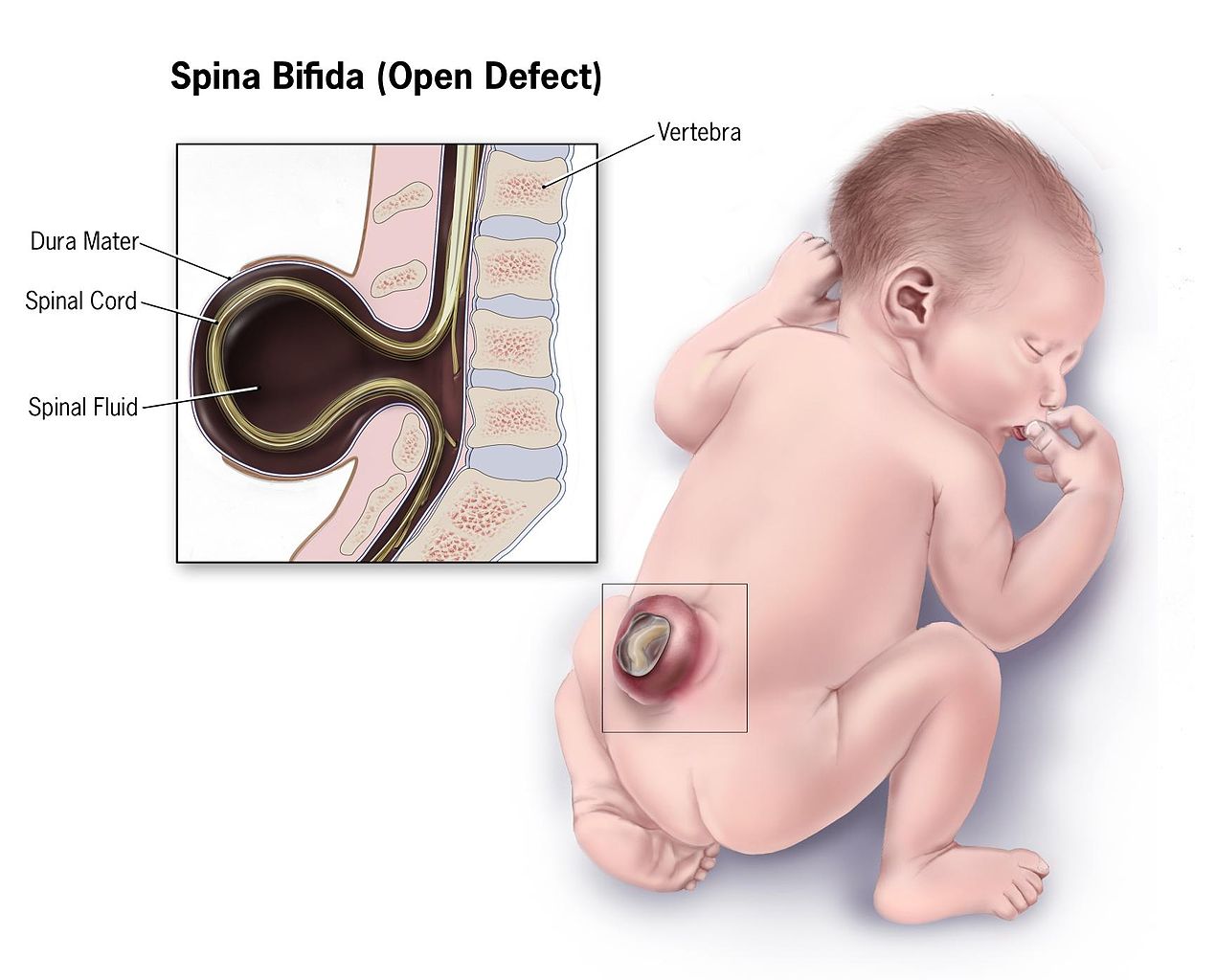

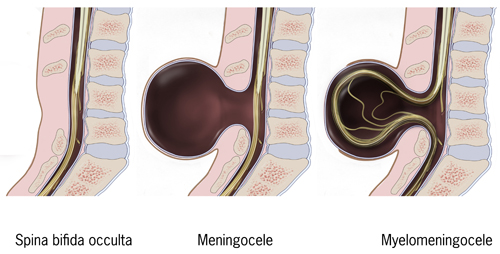

Spina Bifida is a congenital anomaly that arises from incomplete development of the neural tube. It is commonly used as a nonspecific term referring to any degree of neural tube closure. It can be further subdivided into spina bifida occulta and spina bifida aperta. Spina bifida occulta, or closed spinal dysraphism, is the mildest form of the neural tube defects (NTD) which involves a hidden vertebral defect and minimal neural involvement. Spina bifida aperta, or open spinal dysraphism, refers to a defect in which neural tissues communicate with the external environment such as meningocele and myelomeningocele. These conditions result in a varied spectrum of neurological effects due to the degree of neuralization. Spina bifida is commonly associated with several other developmental abnormalities which makes a multidisciplinary medical plan paramount to survival and positive outcomes.

Etiology

These spinal dysraphisms are due to incomplete closure of the posterior spinal elements and typically occur between 17 and 30 days of fetal development. The process of neuralization occurs in two phases, primary and secondary neuralization. Primary neuralization refers to the closure of the neural tube forming the brain and spinal cord. Secondary neuralization involves the formation of the caudal structures of the neural tube forming the sacral and coccygeal portion. These caudal structures develop around day 26 of gestation and closure failure of these portions results in varying degrees of spinal dysraphisms.[1]

Defects in neural tube development are thought to be multifactorial including environmental and genetic influences. The most common environmental cause is folate deficiency with most cases deemed “folic acid-sensitive”. Programs for dietary folate fortification have been implemented across the globe which have decreased prevalence of anencephaly and spina bifida by 28%. Other environmental risk factors include maternal obesity, maternal diabetes, and teratogens such as valproic acid. Valproic acid has the highest association with the development of NTDs carrying about a tenfold increase in risk. Some genetic factors have also been correlated with poor neuralization including several chromosomal syndromes and genetic polymorphism. Research has implicated polymorphism of the gene encoding the MTHFR enzyme, involved in folate metabolism, as a likely genetic risk factor. While NTDs are typically isolated defects, some are associated with chromosomal syndromes, most often Trisomy 13 and 18.[1][2][1]

Epidemiology

Prevalence and incidence of NTDs have varied since it was first recognized but overall has decreased with several interventional programs and increased fetal screening. In the US, the overall prevalence of spina bifida between 1999-2007 was 3.17/10,000 live births. Research shows that about 1,300 healthy babies born each year would have had NTDs if folic acid fortification was not introduced into common prenatal practice. Hispanic women seem to have a high rate of pregnancies affected by NTD. Worldwide, Hispanics have a prevalence of 3.8/10,000 live births as compared to non-Hispanic Black or African Americans which have a rate of 2.73/10,000 and non-Hispanic White with 3.09/10,000.[2][3]

There is also an increased risk for recurrence associated with family history, geographic location, and severity of the defect. It has been reported that there is an increased risk of recurrence of about 3-8% after one affected pregnancy or maternal history of the defect and the risk worsens with an increasing number of affected children.[4]

History and Physical

Patients with NTDs should present during prenatal screening and at-risk females should be counseled before conception to improve outcomes. However, in certain areas, especially underserved communities and those of low socio-economic background, may not have access to proper screening and may present at birth or in infancy. Standard prenatal screening includes serum AFP levels at 16-18 weeks to evaluate for NTD. Follow up can be obtained with ultrasound with a sensitivity of 88-89%.[4] Given the wide variety of neuralization, patients can present with a wide range of symptoms and conditions. Physically, visualization of the lower portions of the spine can determine whether the patient has an open or closed spinal dysraphism. In spina bifida occulta there is no obvious deformity, however, sometimes a hairy patch of skin or dimple can be seen where the expected spinal defect is. Meningocele involves a defect of the posterior elements of the spine with extrusion of meninges and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) without the involvement of the neural elements. Myelomeningocele involves extrusion of meninges, CSF, and functional neural elements such as nerve or spinal cord contents. Myelomeningocele typically affords more functional limitations in the future as nervous tissue is involved in the defect. Patients may present with symptoms of spasticity, pain, motor deficits, neurogenic bowel and/or bladder, cognitive deficits, seizures, and even endocrine disorders such as precocious puberty.[1] Neurological dysfunction is more common in the open dysraphisms such as meningocele and myelomeningocele, as neural tissue can extrude outside the defect and be affected. Patients often also present with latex allergies with a prevalence of 10% and 73% in those with NTDs.[5] Once any of these signs or symptoms are encountered, a detailed gestational, birth and family history should be obtained to understand the likely contributors and help guide family counseling.

Evaluation

As mentioned above, women should undergo routine screening to identify NTD early and help with therapeutic intervention and counseling. Initial screening is done with serum AFP, but in cases of high suspicion amniocentesis can be pursued for confirmation. However, given the risk of amniocentesis and accuracy of ultrasound, the latter has become the gold standard for diagnosis in-utero. Several ultrasound signs have been identified as reliably diagnostic. The small biparietal diameter has been associated with NTD. However, the most cited signs include the lemon sign and banana sign. The lemon sign describes the overlapping of the frontal bones due to a posterior shift of intracranial contents. The banana sign is that of a curved cerebellum due to its downward displacement often leading to Arnold-Chiari II malformation at birth.[4] Ventriculomegaly, even without hydrocephalus, can be seen on ultrasound as well. Ultrasound further down the spine can help visualize the affected vertebral levels and can give prognostic information about effects on the bowel, bladder, gait, etc.[6] The functional level after birth correlates with prenatal ultrasound identified level of injury in 60% of patients.[7] Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can also be used after birth for prognostication within one to two vertebral levels in 89% of cases.[4]

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of treatment of NTDs such as spina bifida is actually prevention. Women of childbearing age should be supplementing their diet with folate to prevent NTDs. The US began to mandate the fortification of grains with folic acid to help diminish cases.[2] Women who are trying to become pregnant should take 0.4mg of folic acid daily before conception while women who have a history of NTD or a previously affected pregnancy should take 4mg of folic acid supplementation.[4] Most patients with spina bifida occulta will not require surgical correction of the defect. However, several surgical interventions could help ameliorate the neurologic effects of open NTDs. In a limited selection of patients, an intra-uterine repair can be pursued to prevent future complications. To qualify for this risky intervention, the fetus must have a lesion from T1-Sacrum, Arnold Chiari malformation, and age 19-25 weeks.[8] These procedures have shown significantly reduced need for ventriculoperitoneal shunt placement in the future, showed adequate repositioning of the cerebellum, and provided improved leg function and ambulation.[1] However, there is a significant risk associated with intra-uterine repair including increased risk of prematurity and severe maternal complications.[8]

In the neonatal stage there are several implications and sequela that must be monitored and managed. Early closure within 72 hours is preferred to prevent significant neurologic decline and minimize the risk of infection or injury to any exposed defect. Patients will often require a ventriculoperitoneal shunt for hydrocephalus after the closure of the defect. Arnold Chiari malformations are common and often require repair however this repair carries significant mortality when patients are symptomatic. Long term management involves an interdisciplinary approach as several organ systems can be affected. Neurogenic bowel and bladder are common manifestations of the condition. Neurogenic bladder typically involves detrusor- sphincter dyssynergia which can lead to renal failure if poorly managed. Patients should have biannual renal ultrasounds for surveillance and may require intermittent catheterization for long term management. Patients also present with neurogenic bowel caused by impaired sensation and poor sphincter control. Patients may need to learn a consistent bowel program which includes stool softeners, motility agents, and digital stimulation for adequate control.

Children with NTDs can present with a wide range of motor involvement including weakness, flaccidity, spasticity, and contractures. Tendon lengthening procedures can be considered for patients with severe contractures that interfere with ambulation, hygiene, or positioning. Foot deformities are common in NTDs and include equinovarus, calcaneus, and rocker bottom deformities. Splinting, passive stretching and serial casting can help with significant spasticity and/or contractures.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of spina bifida is typically accurate based on the physical presentation of the disease. However, it is important to consider several differentials in cases where the physical findings or radiographic diagnosis is not clear:

- Cord compression

- Diastematolyelia

- Isolated Chiari malformations

- Mass lesions

- Tethered cord

Prognosis

There are few recent longitudinal studies on spina bifida and long-term outcomes which makes it difficult to prognosticate for patients given the significant improvements in spina bifida management. Most studies also combine data from patients with both open and closed dysraphisms. Overall, the prognosis depends mostly on the presence of hydrocephalus, level of defect, and severity of Chiari malformation. A recent study showed that survivability up to 1 year of age was about 71% overall. Of those with and without hydrocephalus, 56% and 88% survived beyond age 1, respectively. The rates of survival drop slightly as patients with hydrocephalus age, to about 50% by age 20.[9] Most deaths beyond age 5 are attributed to seizures, pulmonary emboli, hydrocephalus, and acute renal failure/sepsis.[4] However, there is significant morbidity associated with NTDs if patients are not adequately managed. Urinary tract infections are the most common complication faced by those with NTDs secondary to neurogenic bladder, affecting about 48% of patients with 6% ultimately developing renal failure.[4] The severity of Chiari malformation is a significant risk factor for death in infants with NTDs and can have several effects such as sleep apnea, vocal cord paralysis, and bradycardia. Patients often are concerned about functional outcomes, specifically the prognosis regarding ambulation. In the Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS), only 7% were wheelchair dependent for ambulation. The remaining percent can at least ambulate with assistive devices and about 29% were fully independent.[10]

Complications

Patients can present with several complications, a few of which have been discussed above. The most common complication is acute renal failure/urosepsis which is secondary to ureteral reflux caused by neurogenic bladder. It is important to introduce aggressive treatment and surveillance of urologic dysfunction. Many patients will require intermittent catheterization for urinary management. Scoliosis is also a common complication with about 33% of patients affected, followed by chronic pain in 29%, and epilepsy in 12%.[4] Patients may also present with tethered cords or hydromyelia which can present with a sudden neurologic decline, spasticity, or pain. Increased risk of fracture is associated with NTD, as well, likely secondary to osteopenia, contractures, decreased sensation, and immobilization. There is also a unique association with a latex allergy as about 10% and 73% of patients with spina bifida present with latex allergies.[5]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Early rehabilitative intervention is key to improve functional outcomes and quality of life. Early mobilization and stretching can help patients maintain a range of motion for future applications with gait, hygiene, and activities of daily living (ADLs). Most patients have a combination of upper and lower motor neuron symptoms and have varying motor control requiring individualized therapy plans. Patients will also typically require orthotics for joint stabilization, prevention of deformity, gait, and overall improved function. They will also require assistive devices such as crutches, canes, walkers, or wheelchairs for support. Some may require assistive devices for ADLs. Patients should participate in physical and occupational therapy over the long term. Some may require speech therapy for dysphagia, dysarthria, vocal cord paralysis, and cognitive training. Neuropsychology would also be important in the early stages of adolescence to assist with adjustment to complications as they arrive. However, research shows that despite the risk of significant complications, only 5% of patients develop depression.[4]

Consultations

Important consultations include:

-

Urology

-

Endocrinology

-

Orthopedics

-

Neurosurgery

-

Rehabilitation/ Therapy

-

Neurology

Deterrence and Patient Education

Women should be counseled during child-bearing age to take folic acid supplementation to prevent NTDs. As discussed, women planning pregnancy should take 0.4mg daily and those with a family history or previous child with NTD should take 4mg daily.

In the early stages of the conditions, caretakers require the most education to empower them to be effective advocates for the patient during childhood. Throughout growth, patients should be provided with increasing autonomy as appropriate based on their cognitive development. It is important for patients and their caretakers to feel as though they are part of the medical team.

Families must be trained during their child’s therapy so they may be able to effectively care for their children as they age. Important considerations include mobilization of the patient, appropriate use of orthotics and assistive devices, and proper body mechanics. They must also be educated on the signs and symptoms of the serious conditions that may develop including UTI, hydrocephalus, or seizures.

Once children are old enough to understand their condition and needs, they should be included in the decision-making process providing them with education on their self-care. Patients with spina bifida occulta may not have many comorbidities but those with open dysraphisms may require closer monitoring. Patients may need to be taught to self-catheterize or provide their own bowel program.[11]

Many patients will express concern regarding ambulation as they age. As mentioned above, most patients will obtain functional ambulation with only 7% requiring wheelchair level ambulation.

Psychosocial aspects of the patient’s health must also be addressed to improve patient participation in their healthcare and reach improved outcomes. A randomized controlled trial revealed cognitive behavioral therapy in a high-intensity rehabilitation program provided improved outcomes in self-care, cognition and mood, and independence.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multidisciplinary approach medically and from a psychosocial standpoint represents the best outcomes for patients with spina bifida. A team approach involving several specialists and therapy staff can holistically address the spectrum of disease. In an article by Dicianno, the “specialty medical home” is proposed as the ideal management method of spina bifida patients as a variation of the often referenced “medical home model”. In the medical home model, the primary care physician serves as a central hub with all compiled medical information and acts as the referring physician managing the team dynamic between specialists. However, in certain conditions, it has been suggested that the specialty physician act as the medical home as most of the comorbidities being managed stem from the underlying condition. Dicianno recommends this specialty medical home model for spina bifida to encourage teamwork driven by a subspecialist well versed in spina bifida and its sequelae.[13]

This team-based medical care should follow the patient through adulthood but many patients find barriers to a seamless transfer of care into adulthood. It is important to involve parents, caretakers, the transitioning youths, and both the pediatric and adult providers in the transition. Early preparation is key to a smooth transition and should be considered early in the process. Transition to adult care can be difficult for patients, caretakers, and providers as patients usually spend several years of their lives with a specific physician team. The timing of transition should take into account not only the patient’s age but also their cognitive level to ensure the patient is ready to transition out of pediatric care. This transition requires significant cooperation between the pediatric provider, the new specialty provider, and all other possible consultants on the team.[11] (Level V)

This team-based approach involves physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and neuropsychologists to help navigate the disease and its sequelae. A randomized controlled trial by Kahn et al showed that high intensity, multidisciplinary rehabilitation with incorporated cognitive behavioral therapy had significantly improved outcomes in cognitive function, mood, independence, and bowel/bladder dysfunction.[12] (Level II)