Continuing Education Activity

Trichinellosis, also called trichinosis, is a parasitic infection caused by roundworms (nematodes) from the genus Trichinella. It is caused by consuming undercooked or raw meat (usually pork). Trichinella spiralis species is the common cause of human disease and infection occurs after the ingestion of raw or undercooked pork. Symptoms are diverse and may include generalized fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or myalgias. The presentation can also include myocarditis and encephalitis. This activity describes the evaluation and management of trichinellosis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of trichinellosis.

- Outline the typical presentation of a patient with trichinellosis.

- Summarize the treatment considerations for patients with trichinellosis.

- Review the importance of collaboration and communication amongst interprofessional team members to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by trichinellosis.

Introduction

Trichinellosis, also called trichinosis, results from roundworms (nematodes) from the genus Trichinella. It is a parasitic infection. It is caused by consuming undercooked or raw meat (usually pork). Trichinella spiralis species is the common cause of human disease by eating raw or undercooked pork. Other mammals like wild carnivores and horses can be reservoirs of infection. It can cause symptoms varying from generalized fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, myalgia to more severe like myocarditis and encephalitis.

Etiology

Trichinella spiralis is a nematode (roundworm) parasite.[1] It possesses the capability of infecting a wide range of mammals including pigs, horses, reptiles, and birds but it causes disease only in humans. By eating improperly cooked or raw pork, horse, or other domestic animal meat and wild game meat like bear, humans acquire the infection. Some reports have mentioned an occasional acquisition of the disease by ingestion of reptile meat, including lizards and turtles.[2] There are no reports of human to human transmission.

Epidemiology

Trichinellosis occurs worldwide, and estimates are that about 10000 cases occur each year.[3] Cases usually tend to occur in clusters among groups of people who have consumed infected meat from a common animal.[4] There are nine species of Trichinella, and thus far reports exist of twelve genotypes of Trichinella.[5] The most common species of trichinella which can cause human disease is Trichinella spiralis, although other species of Trichinella implicated in human disease are: T. nativa, T. nelson, T. britovi, T. pseudospiralis, T. murelli, T. papuae.[5][6] Per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention around 400 cases of trichinellosis were reported every year in the 1940s, but now the number of reported cases has dropped significantly and has been around 20 cases every year from 2008 to 2010. The majority of individuals at risk include hunters and others who eat meat from wildlife.

The highest number of cases appear to be in China where pig consumption is the highest in the world. In the arctic, polar bears, seals, and walrus have been identified as vectors for Trichinella. In recent years, consumer preference for eating antibiotic-free meat has also led to an increase in Trichinella in Europe.

Pathophysiology

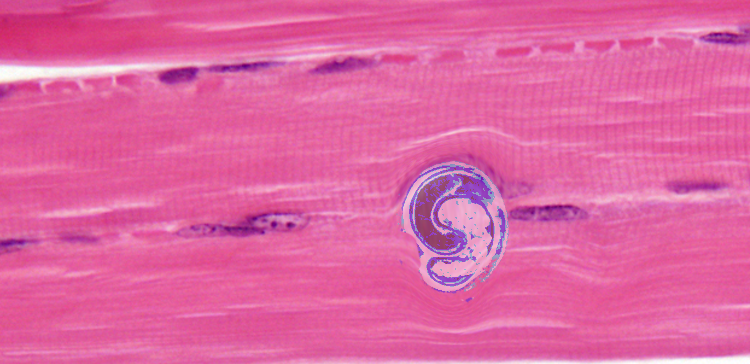

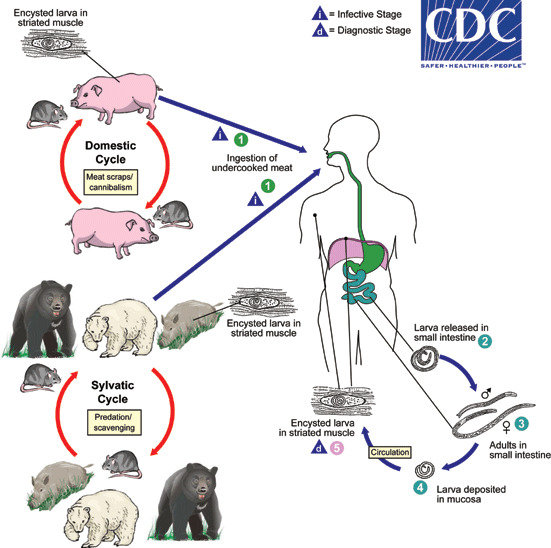

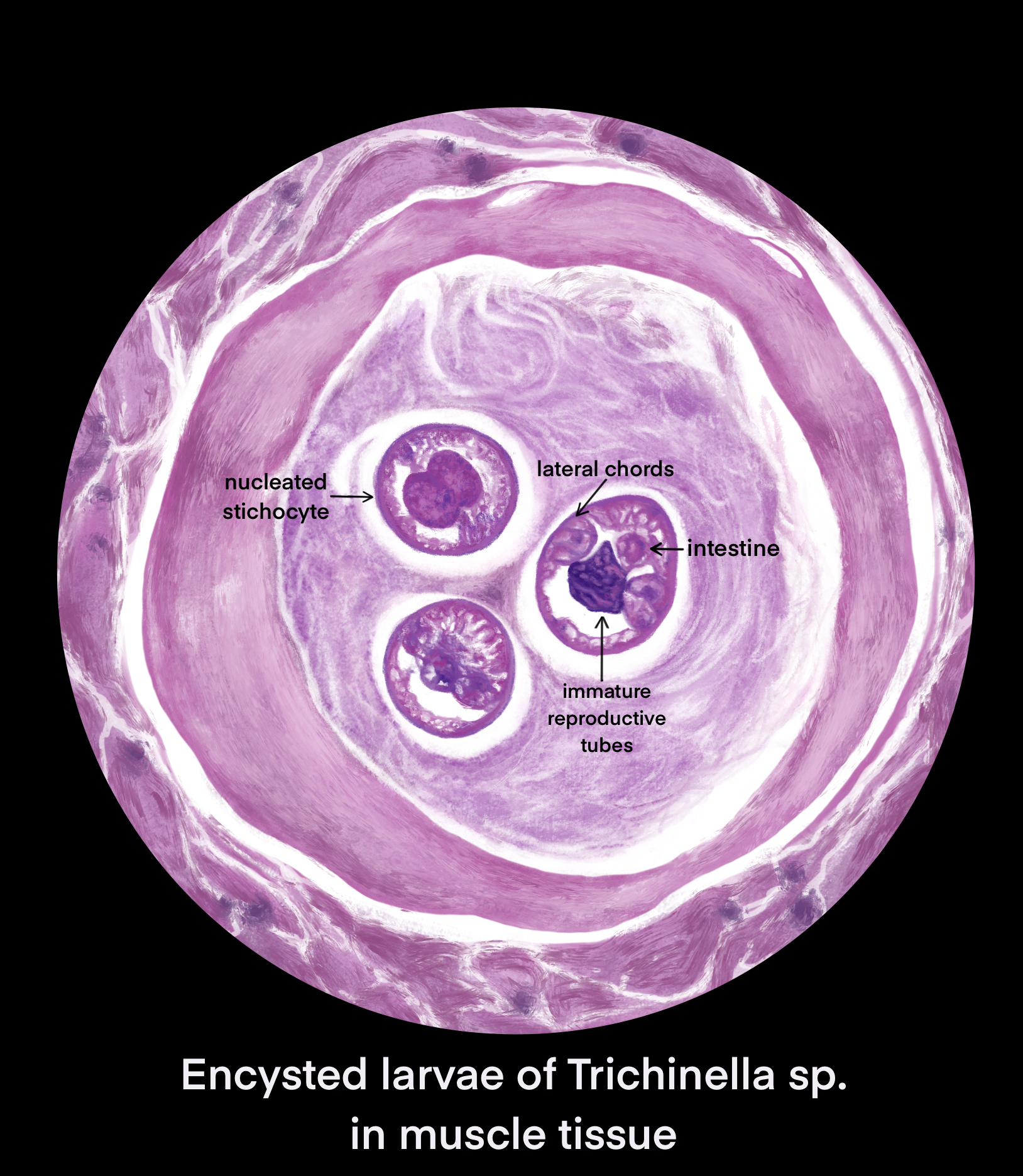

Ingestion of undercooked or raw meat from domestic or sylvatic animals containing encysted larvae of Trichinella species can lead to Trichinellosis. T. spiralis results from the consumption of inadequately cooked or raw pork from domestic pigs.[7]

Enteric or gastrointestinal phase: After ingestion of infected meat by humans, the enzymes pepsin and hydrochloric acid act in the stomach and cause the release of the 1st stage of the larvae. These larvae invade the small intestine. Invasion can be asymptomatic or sometimes associated with abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Larvae then turn into adults and mate. Female trichinella worms produce larvae, which completes the gastrointestinal or enteric phase.

Systemic (parenteral) phase: Larvae enter the lymphatic circulation and then into the blood, reaching skeletal muscles, myocardium, and brain which are high in oxygen content. This phase leads to systemic symptoms like fevers, myositis, myalgias, periorbital edema and can even cause myocarditis and encephalitis.

The larvae provoke significant eosinophilia, especially in patients who develop cardiac and CNS dysfunction.

Life cycle:[3]

- The life cycle of trichinellosis divides into two stages: 1) domestic cycle and 2) sylvatic cycle

- Domestic cycle: Affects domestic animals, particularly swine, rodents, and horses

- Sylvatic cycle: Affects wildlife like bear, wild boar, and moose

History and Physical

Infection results from the consumption of raw or undercooked meat (especially pork). The incubation period is 1 to 6 weeks. In humans, the severity of infection is related to the number of larvae ingested.[8] Gastrointestinal symptoms are the first symptoms of trichinellosis. They usually occur in 2 to 7 days after consumption of raw or undercooked meat. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Muscle pain is a common complaint, chiefly in the mid-abdomen, face (masseter), and chest (intercostal muscles). In some cases, the pain can be so severe, that the individual is disabled and may not be able to perform activities of daily living.

Classic trichinellosis symptoms usually occur in 2 weeks after consumption of raw or undercooked meat and can last up to 8 weeks. Symptoms include fevers, chills, myalgias, periorbital or facial edema, weakness, and fatigue. Reports also exist of prolonged diarrhea.[9]. Other common symptoms are conjunctivitis and subconjunctival hemorrhages seen in about 50% of patients.[10] Splinter hemorrhages on nailbeds (subungual) and retinal hemorrhages can also occur. The rash is most commonly in the form of urticaria but can present with splinter hemorrhage and petechiae. A key finding is palpebral edema which is often associated with proptosis and chemosis. Other less common manifestations include a headache, cough, rash, headache, dyspnea, and dysphagia. Hepatomegaly can also occur occasionally.[11] Severe complications include myocarditis, life-threatening arrhythmias, meningitis, encephalitis, respiratory myositis, secondary bacterial pneumonia, hematuria, and renal failure.[12][13][14][15]

Evaluation

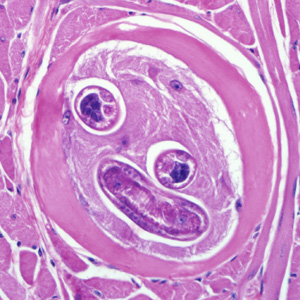

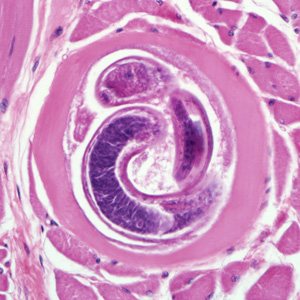

Diagnosis is initially made usually based on clinical signs and symptoms. Diagnostic confirmation is by serology, or occasionally muscle biopsy may be needed.

A complete blood count can show leukocytosis and eosinophilia, which correlates with the number of worms causing the infection.[3] Creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, aldolase, and aminotransferases can be elevated due to the invasion of skeletal muscle by parasites causing muscle destruction. Patients can also have hypokalemia, hypoalbuminemia, and increased serum IgE levels. All these tests are non-specific as they can be seen in other parasitic diseases and autoimmune diseases.[16]

Serological tests that are available are ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), indirect IF (immunofluorescence), and latex agglutination test. Serologic test confirmation can be via western blot.[17] Sometimes serology is not reliable mainly during the early course of the disease (during the first 3 weeks or more). Infection with other organisms like nematodes or other helminths and autoimmune diseases can cause a false positive serologic reaction.

Plain x-rays may show calcific densities in the muscles. A computed tomography (CT) scan is done to rule out other causes of neurological dysfunction.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) may show features of pericarditis, ischemia, or myocarditis. There may be premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), PR interval prolongation, conduction block, or atrial arrhythmias.

The definitive diagnosis method is a muscle biopsy.[10] Sensitivity is high if the biopsy is performed 4 weeks after infection. If performed early in the disease course it may be negative.

Treatment / Management

The clinical course of trichinellosis is self-limited in most cases, and it is uncomplicated. Mild infections are treated symptomatically with antipyretics and anti-inflammatory agents.

Trichinella infection with systemic complications is treated with antiparasitic agents and corticosteroids.[18] Antiparasitic agents that can be used include albendazole 500mg twice a day given orally for 10 to 14 days, mebendazole 200 to 400 mg three times a day for 3 days, then 400 to 500 mg three times a day for 10 days. Severe cases may require coadministration with prednisone at a dose of 30 to 60 mg daily for a total of 10 to 14 days.

Albendazole and mebendazole are not considered safe in pregnant women and children less than or equal to 2 years of age. Specialist consultation is necessary in these cases and risk, and weighing the risks versus benefits is necessary before administering these medications. The World Health Organization's recommendations are that pregnant women can get antihelminthic medications (mebendazole, albendazole, pyrantel, or levamisole) after their first trimester.[19]

Cardiac monitoring may necessary for patients with cardiac involvement.

Postexposure prophylaxis with mebendazole if given within 6 days of exposure may be effective.[20]

Differential Diagnosis

- Gastroenteritis - viral or bacterial

- Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (autoimmune)

- Periorbital cellulitis

- Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome

Eosinophilia can be present in other helminthic infections like fasciola, schistosomiasis, toxocariasis, cysticercosis, visceral larva migrans, and sarcocystosis.

Prognosis

Trichinellosis usually has a benign course and is self-limiting. Full recovery of patients within 2 months to 6 months of infection is the expectation. However, some cases might be severe, and even death is a possibility. Death is rare if the cardiac and CNS remain uninvolved. Some individuals with CNS involvement may have residual deficits long-term. The prognosis of the disease proportionately correlates with the parasitic burden.

Complications

- Myocarditis

- Pneumonitis

- Secondary bacterial pneumonia

- Nephritis

- Chronic diarrhea

- Neurotrichinellosis

Consultations

- Infectious disease

- Cardiology if complications like myocarditis or arrhythmias arise

- Surgical consultation might be necessary for a muscle biopsy

Deterrence and Patient Education

Trichinellosis is caused by consuming raw or undercooked meat of infected animals. Patients should receive education about the risk of transmission when consuming undercooked or raw meat. There are no reports of human to human transmission. Cases can occur in clusters among groups of people from the same community or family who have consumed infected meat from a common animal. Patients should be educated to heat the meat to at least 77 degrees Celsius which kills Trichinella larvae. Patients should also receive counseling regarding proper food safety practices.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Treatment and prevention of trichinellosis require an interprofessional team effort. Collaboration and effective communication between the healthcare team is crucial to ensure excellent patient care. Infectious disease consultations should be sought when necessary to provide the best treatment options for the patient. Nurses should educate patients on risks of transmission when consuming undercooked or raw meat. Pharmacists, nurses, and clinicians should be aware of the potential side effects of antihelminthic medications used in the treatment of trichinellosis and should explain the associated side effects to the patients. When a patient is diagnosed with trichinella, the team should communicate so that the standard of care treatment is provided.