Continuing Education Activity

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis and is fairly common, often affecting infants and young children. Cutaneous lesions usually resolve spontaneously and most patients have an unremarkable course. Ocular JXG can occur and has an increased incidence in those 2 years of age or younger or in those with multiple lesions. Ocular involvement can be associated with many potential complications including blindness. There is an association of JXG with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Objectives:

- Outline the risk factors for xanthogranulomas.

- Describe the typical presentation of a patient with a xanthogranuloma.

- Review the pathophysiology of xanthogranulomas.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with xanthogranulomas.

Introduction

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) is a relatively common entity and is the most common form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytic disorder of childhood.[1], [2] It is estimated that in 75% of cases, lesions appear during the first year of life, with >15-20% of patients having lesions at birth. JXG is rare in adults, with a peak incidence in the late twenties to thirties. Rarely, reports exist of lesions arising in the elderly. The majority of adult patients have solitary lesions.[3] The true incidence, however, may be underestimated, as many lesions, especially those which are solitary and small (up to 90% of all patients), may go unrecognized. Typically, the clinical presentation consists of solitary or multiple yellow-orange-brown firm papules or nodules. The most common locations are the face, neck, and upper torso.[3] Oral lesions are rare and often occur as a yellow nodule on the lateral aspects of the tongue. Oral lesions can also arise on the gingival, buccal mucosa, and midline hard palate and may ulcerate and bleed. Lesions of the oral mucosa may appear verrucous, umbilicated, pedunculated, or fibroma-like. Cutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic, and most lesions spontaneously involute over the course of several years. Although occurring rarely, ocular involvement is the most common extracutaneous site involved, followed by the lungs. Ocular JXG is nearly always unilateral and develops in less than 0.5% of patients. Approximately 40% of patients with ocular JXG, however, have multiple cutaneous lesions at the time of diagnosis. Ocular disease usually occurs prior to 2 years of age and commonly affects the iris. Hyphema and glaucoma are serious complications that can result in blindness and necessitate early referral to an ophthalmologist for evaluation and possible treatment. Other bone, visceral and or CNS involvement (e.g. diabetes insipidus) is unusual. Disease-related deaths are rare.[1]

As opposed to other xanthomatous diseases, juvenile xanthogranulomas are not associated with metabolic or lipid disorders.[3]

Etiology

It is presumed that juvenile xanthogranulomas develop after unknown stimuli (infectious or physical) and provoke a granulomatous histiocytic reaction.[3] However, the true etiology of juvenile xanthogranuloma is currently unknown, and conservative management is generally advised.[4]

Juvenile xanthogranulomas have been associated with juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia (JMML).[5] Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) is also seen in patients with neurofibromatosis (the incidence is between 1:2000 and 1:5000). Rarely, it is seen in patients with both juvenile xanthogranuloma and neurofibromatosis.[4] However, when this does occur, these children have a 20- to 32-fold increased risk of juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia when compared to patients with neurofibromatosis alone.[6]

Other diseases associated with juvenile xanthogranuloma include the following: urticaria pigmentosa, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, aquagenic pruritis, and even cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.[5]

Epidemiology

Juvenile xanthogranulomas are most commonly found in early childhood with >15-20% of patients having lesions at birth. It is estimated that in 75% of cases, lesions appear during the first year of life.[1] Approximately 10% of cases may appear in adulthood and are known as adult xanthogranuloma.[1] In children, the disease most often affects males; however, in adults, there is no sex prevalence.[3]

Histopathology

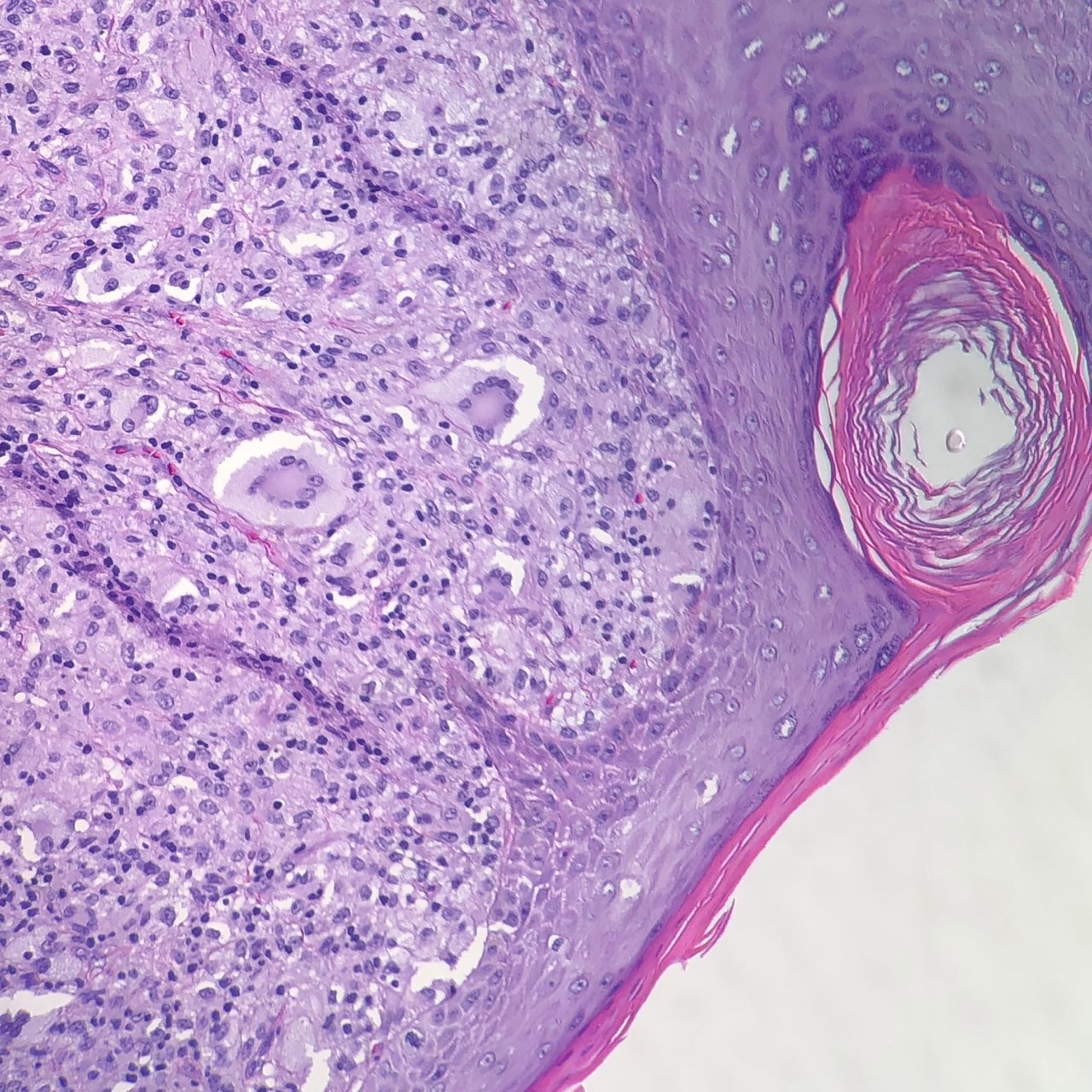

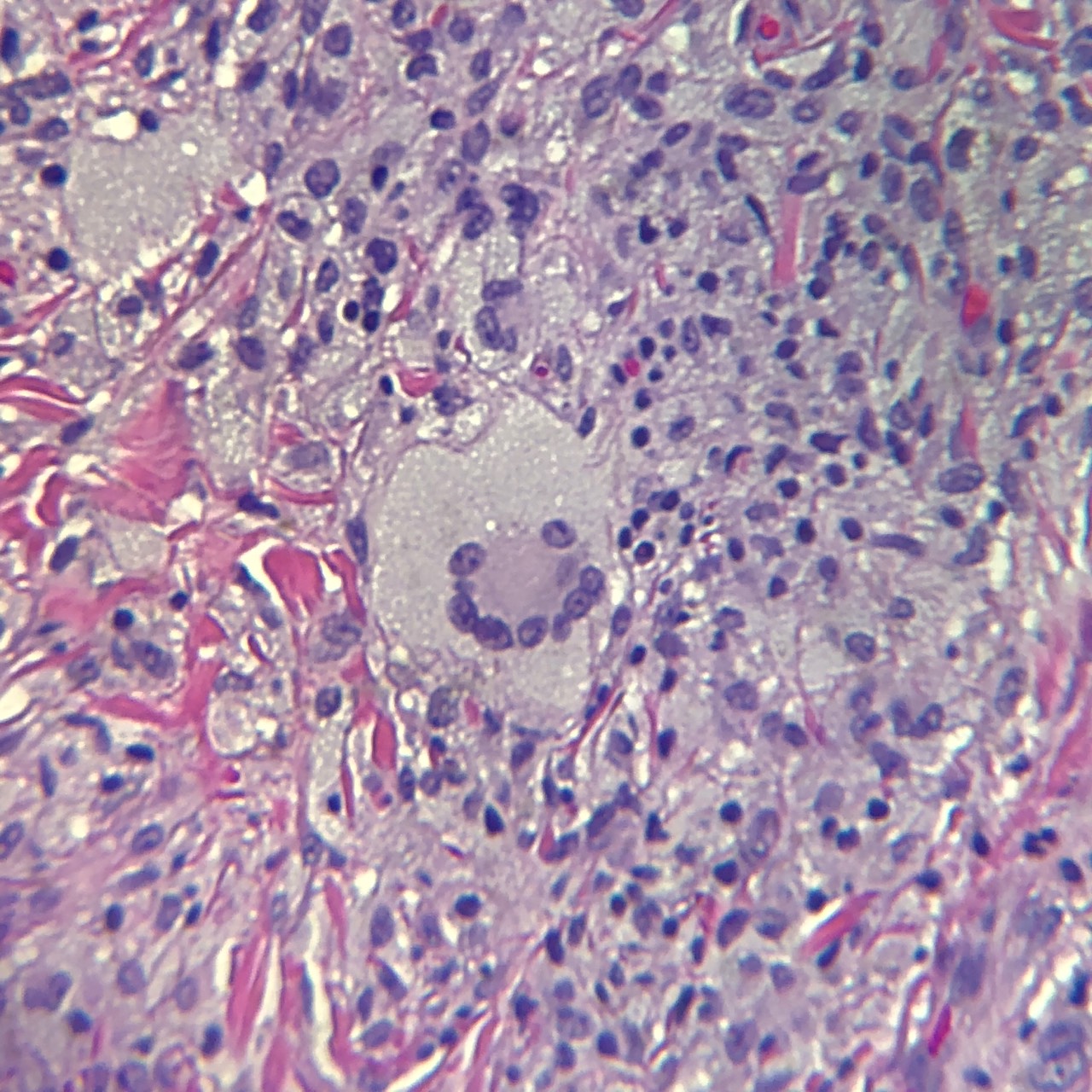

Juvenile xanthogranulomas occur most commonly in the skin and show a characteristic morphology. The lesions exhibit a well-demarcated, dense invasion of numerous histiocytes within the superficial dermis and blunting of the rete ridges along with scattered lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils.[1] Of note, the mononuclear cells may show a spindled or elongated appearance.[5] Foam cells, foreign body giant cells, and Touton giant cells may be seen in the mature stage.[1] The characteristic multinucleated giant cell (Touton cell) is observed in 85% of juvenile xanthogranulomas, and these appear garland-like.[3][1] At the late stage of the lesion, fibroblasts are increased, and fibrosis replaces the infiltration.[1]

In ocular involvement, the tumor cells have abundant cytoplasm and show decreased numbers of Touton cells as compared to cutaneous juvenile xanthogranulomas.[1]

Lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma classically stain with the following markers: CD68 or Ki-M1P and anti F XIIIa, vimentin, and anti-CD4.[1]

History and Physical

Juvenile xanthogranuloma generally occurs in two forms.[7] The first form is composed of multiple 2 to 5 millimeter dome-shaped papules that take on a pink to reddish brown hue and, subsequently, turn yellow.[7] The second form is composed of one or more large nodules which measure 1 to 2 centimeters.[7] Other variants and presentations include giant juvenile xanthogranuloma, atrophic plaque, cutaneous horn, and subcutaneous mass.[7]

Serious complications can arise when systemic juvenile xanthogranulomas develop. Systemic juvenile xanthogranulomas develop in 4% of children, with an overall mortality of 5% to 10%.[6] Fatalities are usually due to progressive central nervous system (CNS) disease or liver failure.[6] Extracutaneous juvenile xanthogranulomas most commonly affect the eye, and ocular involvement has been seen in 0.3% to 10% of children with cutaneous juvenile xanthogranulomas.[1] Most patients with eye lesions are young children (less than 1 year).[3] The iris is most commonly involved, and complications can arise that lead to spontaneous intraocular hemorrhages, glaucoma, and even blinding eye disease.[1] Of importance, spontaneous hyphema with or without increase of intraocular pressure is a common sign of iris juvenile xanthogranuloma.[8]

Other CNS complications include seizures, increased intracranial pressure, diabetes insipidus, and developmental delay.[6] These extracutaneous lesions may also be seen in the deeper soft tissues, spleen, and lung.[6]

Evaluation

Dermoscopy is a noninvasive technique used as an aid in the diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma. It shows a characteristic setting sun appearance (red-yellow center and discrete erythematous halo). Complete removal via surgical excision gives diagnostic confirmation. [2]

Treatment / Management

Curative skin excisions may be performed in easily accessible sites; however, most lesions in childhood spontaneously involute and require no therapy.[6]

Management of non-cutaneous (internal) lesions poses greater difficulty and may include any combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunosuppression.[3] In general, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are options for the patient with symptomatic, unresectable, or incompletely resected extracutaneous disease.[4]

Patients with concurrent neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) should receive frequent followup with a complete blood count to monitor for juvenile chronic myelogenous leukemia (JMML).[6]

Eye exams are recommended for high-risk patients. Topical, intralesional, and subconjunctival corticosteroids may be administered for ocular involvement. If complications arise (i.e., glaucoma or hyphema), surgery or systemic steroids may be required. [6]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential of juvenile xanthogranuloma includes both benign and malignant entities, depending on the clinical presentation and site of involvement.

One of the main differential diagnoses of juvenile xanthogranuloma is Langerhans cell histiocytosis (both may exhibit eosinophils). Helpful morphologic features for Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) are grooved vesicular nuclei with a coffee bean" appearance.[9] Additionally, immunohistochemistry shows that the cells of LCH are positive for CD1a and S-100, whereas the cells of juvenile xanthogranuloma are negative for CD1a and S-100.[9] Recall that CD1a is a fairly specific marker for Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and this marker is not expressed in non-LCH diseases.[1]

Reticulohistiocytoma (another non-LCH histiocytic disorder) has a histologic appearance similar to juvenile xanthogranuloma.[9] This lesion demonstrates large mononucleated or multinucleated histiocytes with a lymphocytic infiltrate and dermal fibrosis.[9] Although positive for CD68, these are negative for vimentin (unlike juvenile xanthogranuloma).[9]

Although juvenile xanthogranulomas may be found in uncommon locations (i.e., vulva), it is important to remember that other entities (such as embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma) may have a similar histologic appearance and should be ruled out.[9] The morphologic appearance of monomorphic small round cells with a cambium layer and necrosis would help direct to a malignant diagnosis in such cases.[9]

Other considerations for the differential diagnosis include other xanthomatous lesions, mastocytomas, dermatofibromas, and Spitz nevus.[4]

Prognosis

The prognosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma is generally excellent with most lesions undergoing spontaneous involution over the course of 3-6 years. Lesions which are of cosmetic concern or pose a risk to vital functions can be treated.[6]

Complications

There are often minimal to no complications of JXG due to its self-limiting nature. Occasionally, lesions are removed for cosmetic concerns. Ocular lesions often require intervention to avoid potential complications of blindness, glaucoma or hyphema.

Consultations

Ophthalmology

Pearls and Other Issues

Isolated intracranial lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma have been shown to carry a more favorable prognosis (as opposed to other examples of systemic disease). These lesions have been reported to have a BRAF V600E mutation akin to Langerhans cell histiocytosis and Erdheim-Chester disease. However, further study with a larger patient population is necessary to interpret these findings. [10]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of solitary lesions of juvenile xanthogranuloma is often straightforward with routine observation. When multiple lesions are present and or there is the involvement of vital structures, management is best accomplished with an interprofessional team. While skin lesions can be excised, those occurring in other parts of the body may cause compression or obstruction of vital tissues. The outcomes for patients with skin-only lesions is favorable but those with lesions in the CNS may suffer from complications of surgery.[11][12][13] (Level V)