Continuing Education Activity

Epiphora is a common presentation to the general ophthalmologist. Causes of epiphora may be caused by secretory problems or problems with the excretory side of the lacrimal system. This activity describes the pathophysiology of epiphora, comprehensively reviews the causes of epiphora, and discusses the best relevant examination techniques that apply to patients with epiphora. Important anatomical and physiological factors that apply to patients with epiphora are discussed. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team.

Objectives:

Describe the many causes of epiphora with an analysis of the anatomical and physiological factors.

Review the findings of epiphora.

Outline the specifics of the degree of intervention needed for epiphora.

Epiphora causes significant morbidity and is a common problem seen in ophthalmic clinics. With an appropriate review of the history and a methodical examination, the treating interprofessional team can ascertain the diagnosis and suggest treatment. Accurate diagnosis is vital in these patients, as many patients with epiphora will also have dry eyes.

Introduction

Patients will frequently present with "a watery eye" or "a tearing eye." Historically, this was called epiphora, but there have been recent variations in the use of different terms.

Lacrimation (or lachrymation) is derived from "lacrima," Latin for tear, and essentially means "production of tears," although it is often used to describe the "shedding of tears" or to cry. Lacrimation may be basal (basic tear production), reflexive (to stimuli such as surface irritation, glare, corneal ulcer, corneal exposure), and psychic (emotional). It is thought that animals do not exhibit emotional lacrimation, although recent observations of elephant mothers responding to their dead offspring have reignited this debate. The sympathetic innervation to the lacrimal gland is thought to stimulate basal tear secretion. Basal tear production decreases with age, resulting in progressive acinar atrophy, fibrosis, and lymphocytic infiltrates. Normal basal tear production is 2 microliters per minute (10 ounces per day).[1][2] It may be stated that lacrimation, whether used to imply the "production of tears" or tearing from emotion or stimuli, implies the production of tears in a normal person without and blockage of the excretory system.

Epiphora

English texts from at least 1475 have used epiphora to mean tearing or excessive tearing. It essentially means an abnormal overflow of tears from the eye onto the face. The cause is not specified. Lately, there has been a tendency to apply the word epiphora only to tearing caused by an obstruction. This does not have any historical accuracy, and the temptation to use it in this manner should be resisted.

The word derives from ancient Greek epifora: "epi" means "on," "upon," or "in addition," and "phérein," meaning "bring" or "carry." The literal meaning of the word epiphora is "to bring upon." This symptom is known to have been described in Egypt (1500 BC) and by Hippocrates (460 BC to 370 BC). Epiphora applies to excessive tearing caused by excessive tear production or secondary to poor drainage. Epiphora is sometimes subdivided into

- Gustatory epiphora ("crocodile tears" caused by aberrant nerve regeneration)

- Reflex epiphora (reactive tear production caused by any ocular surface trauma or stimulation)

- Obstructive epiphora (punctal, canalicular, lacrimal sac, or lacrimal duct occlusion)

- Hypersecretory epiphora is the production of excessive tears. This is very rare.

Plerolacrima

Patients often present with the complaint that they have "a pool of tears in the eyes that interferes with vision," but not frank epiphora. This is also sometimes seen in patients after a dacryocystorhinostomy, where the tear flow may be improved, but the obstruction is not completely corrected. Ian Francis, a classically trained and thinking surgeon, coined the term "plerolacrima" in 2002.[3] He derived it from the Greek "plero" (meaning full) and the Latin "lacrima" (tears). He noted that it was a similar derivative to the one H. M. Traquair of Edinburgh coined in 1927: "plerocephalic edema" to indicate optic nerve edema caused by raised intracranial pressure. We feel this is a useful term that completes the types of excessive tearing or pooling of tears that bother patients and is deserving of an addition to our medical lexicon.

Symptoms: Epiphora can cause blurry vision, discharge if there is a lacrimal sac infection, mucoid discharge if there is a canalicular foreign body, eyelid skin excoriation from constant wiping and laxity of the lower eyelids from constant wiping

The tear film is comprised of three layers:

- an innermost mucin layer produced by goblet cells of the conjunctiva, which are found mostly in the fornices

- an aqueous layer produced by the lacrimal glands and a minor portion from the accessory lacrimal glands of Wolfring and Krause.

- an outermost lipid layer produced by the meibomian glands and Zeis and Moll glands (found on the eyelid margin).[4]

The mucin layer creates a wettable surface on the cornea. The aqueous layer provides a smooth surface and hydration. The lipid layer reduces surface tension and increases tear break-up time. Tears are secreted at a basal rate as well as reflexively in response to stimuli. Dysfunction of any of these components contributes to surface disease and abnormal tearing, resulting in discomfort, altered light refraction, and blurred vision.

The lacrimal system has secretory and excretory components. Normally, there is a balance between tear production and drainage. When this balance is affected, either the secretory or the excretory component may produce epiphora.

The secretory lacrimal system produces tears. The main lacrimal gland is located in the lacrimal fossa of the frontal bone, divided into orbital and palpebral lobes by the lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis. Accessory lacrimal glands are located in the fornices and eyelids. The trigeminal nerve, the facial nerve, sympathetic innervation, and parasympathetic innervation stimulate tear production from the lacrimal glands.

The Secretory System is composed of (fig 1)

- The Main Lacrimal Gland

- The orbital lobe

- The palpebral lobe

- Accessory Lacrimal Glands

- Glands of Krause

- Glands of Wolfring

- Mucin Secretors

- Goblet cells

- Glands of Manz

- Crypts of Henle

- Oil Secretors

- Meibomian glands

- Glands of Moll

- Glands of Zeis

The anatomical excretory lacrimal system drains tears. Tears drain from the ocular surface via puncta in the lower and upper eyelids, into the ampulla, and then through the canaliculi. In 90% of people, the upper and lower canaliculi join to form a common canaliculus. The canaliculi drain into the lacrimal sac, followed by the nasolacrimal duct, which opens in the inferior meatus of the nose. Blockage can occur within any of these components. Both positive and negative pressure systems have been proposed as mechanisms of tear flow through the excretory lacrimal system.

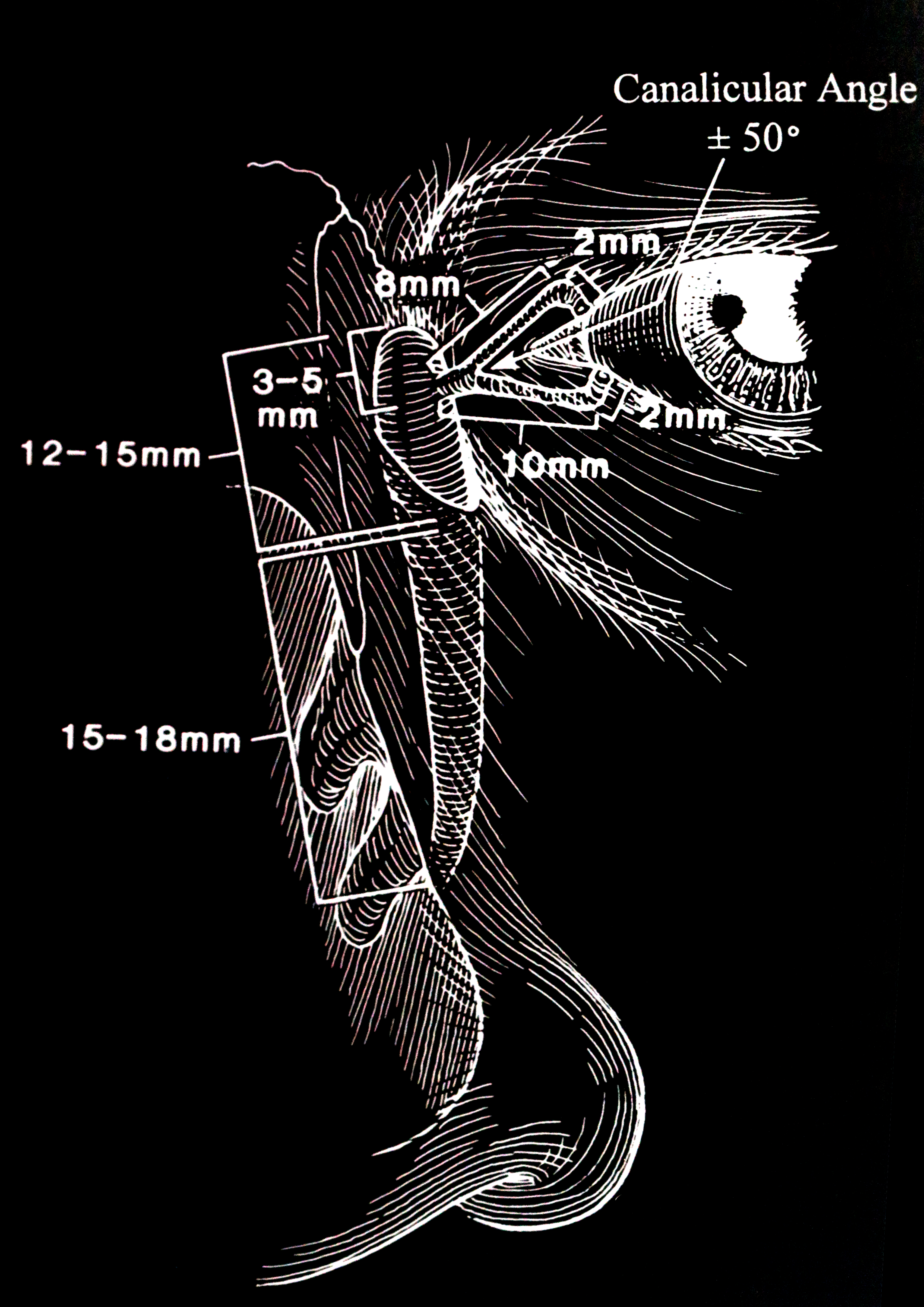

The anatomical excretory system (the punctum, the canaliculus, and the common canalicular opening are termed the upper lacrimal system, and the lacrimal sac and the nasolacrimal duct are termed the lower lacrimal system) is composed of (figs 2, 3):

- The puncta

- The canaliculus

- Vertical component 2 mm upper and 2 mm lower

- Horizontal component 8 mm upper and 10 mm lower

- Common canalicular opening into the lacrimal sac

- Lacrimal sac

- 12 to 15 mm vertical height

- 4 to 8 mm anteroposteriorly

- 3 to 5 mm in width

- One-third of the lacrimal sac is above the medial canthal tendon.

- Nasolacrimal duct

- Measures 12 to 18 mm

- The nasolacrimal duct angulates 15% posteriorly and 15 to 30 degrees laterally.

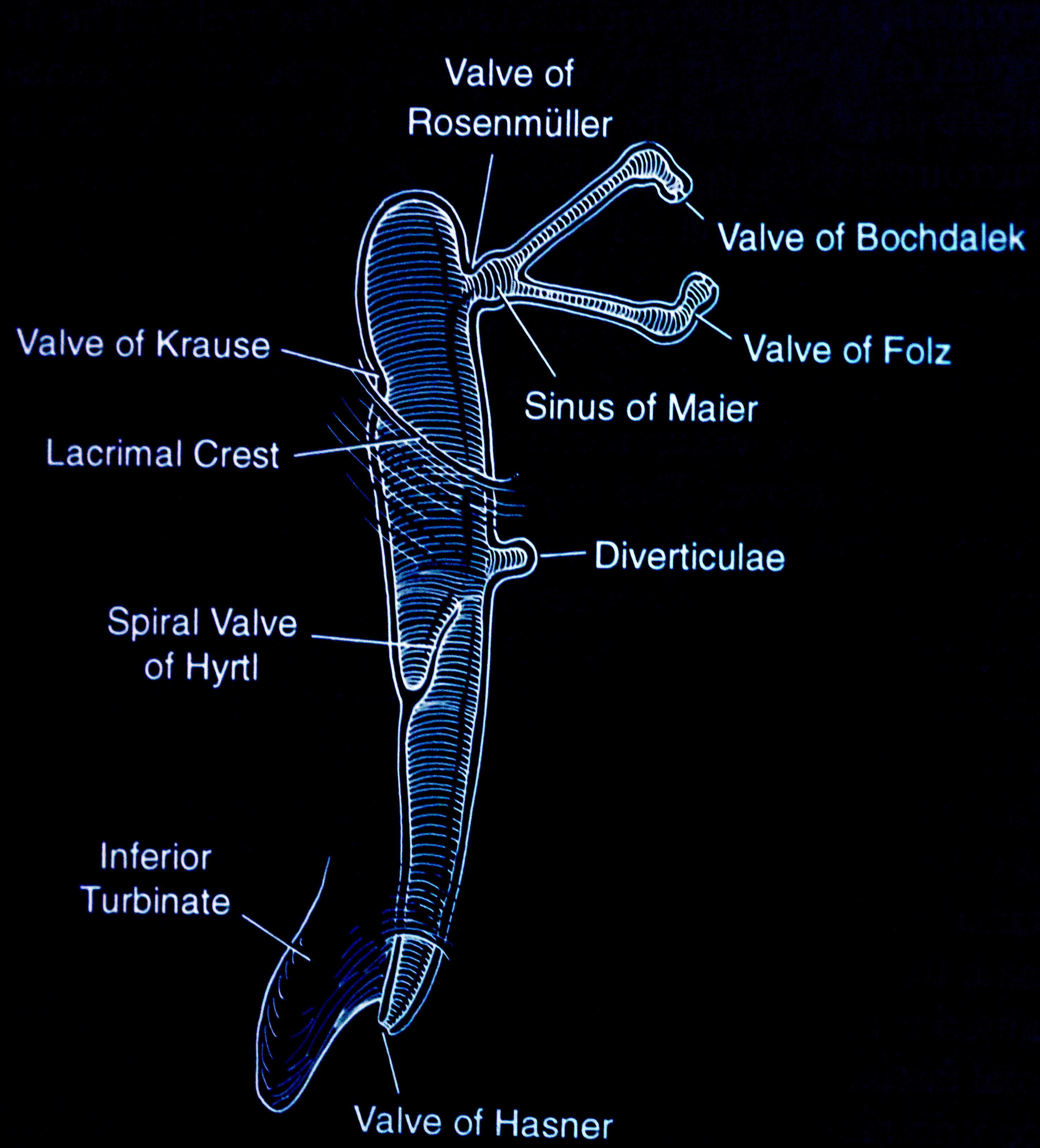

- Valves and sinuses

- Valve of Bochdalek

- Valve of Folz

- Sinus of Maier

- Valve of Rosenmuller is the angulation of the common canaliculus as it enters the lacrimal sac

- Valve of Krause

- Valve of Hyrtl

- Valve of Hasner is the most important valve as an imperforate membrane here causes congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Lacrimal sac and duct diverticula

Functional Excretory System

As one blinks, the orbicularis oculi muscle contracts: the pretarsal and preseptal orbicularis muscles each have a deep medial head. The contracture causes dilatation of the lacrimal sac and a suctioning effect. The lower eyelid rides upwards, and the punctum moves inwards. Tears are drawn into the punctum, canaliculus, and lacrimal sac by this pump mechanism. This pump mechanism is disturbed in the presence of facial nerve palsy.

Etiology

The etiology of epiphora is divided into:

- Reflex tearing is secondary to inflammation, allergy, ocular surface disorders, trichiasis, foreign bodies, trauma, and dry eyes.

- Reduced tear outflow may be caused by many factors, including lid malposition (ectropion, retraction), eyelid laxity, facial nerve palsy causing tear pump dysfunction, or obstruction of the excretory component of the lacrimal system as seen in canalicular obstruction, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, punctal occlusion, plugs in tear ducts, and congenital maldevelopment of the nasolacrimal duct.

- Hypersecretion of tears: primary hypersecretion of the lacrimal gland is very rarely seen. The commonest type of hypersecretion of tears is seen with aberrant nerve regeneration after facial nerve palsy.

Epiphora in adults is a nonspecific finding, representing a broad array of diseases that can cause excessive basal tearing or excessive reflexive tearing secondary to decreased basal tearing. Frequently, more than one factor may cause epiphora. Patients will frequently complain that their eyes tear when they are in the wind or cold: this type of tearing can be seen in normal eyes, in the presence of keratitis sicca, or partial nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Tearing that occurs when indoors is often caused by lower eyelid malposition or nasolacrimal outflow obstruction. Older patients are likely to have more eyelid malposition and multiple factors as causes of the epiphora. In younger patients, eyelid malposition is less common; nasolacrimal duct obstruction, punctal stenosis, or canalicular obstruction is more common. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction affects women more than males (65% to 73%).[5][6] This is thought to be because the narrower nasolacrimal ducts and the longer lacrimal canals are the cause of this increased female preponderance. Epiphora in infants is most commonly caused by congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO).[7]

Epiphora may be unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral epiphora is more likely caused by local conditions (nasolacrimal duct obstruction, foreign body). 75% of cases of nasolacrimal duct have unilateral obstruction. Bilateral epiphora may be caused by oversecretion of tears, as seen in keratoconjunctivitis or allergies. Eyelid malpositions are also more often seen in patients with bilateral epiphora. Bilateral epiphora can also be caused by local conditions, which may result in more epiphora on one side.

Epidemiology

Epiphora is a common problem in children. In a large epidemiological study, MacEwen et al. found the prevalence of epiphora to be 20 percent in the first year of life in British infants. Interestingly, 95% of these children presented with symptoms by the age of one month.[7] With age, there is an increase in the number of patients who present with epiphora because of age-related laxity of the lower eyelids, increasing incidence of nasolacrimal duct obstruction, and other associated diseases (facial nerve palsy). Nasolacrimal duct obstruction causing epiphora is more common in women. The incidence of nasolacrimal duct obstruction is 20.24 per 100,000. Nasolacrimal duct obstruction accounts for 31.8% of patients presenting with chronic epiphora. Nasolacrimal duct obstructions cause 67.6% of all lacrimal pathway obstructions.[8][9]

History and Physical

History

The following factors need to be determined when a patient presents with epiphora:

- Sudden or gradual onset: the sudden occurrence of tearing usually points to local factors

- Duration: nasolacrimal duct narrowing and associated tearing develop gradually, usually

- Seasonal or not

- Diurnal variation: tearing and pain first thing in the morning can suggest a recurrent corneal erosion

- Unilateral or bilateral

- Constant or intermittent

- Severity

- Pain: local causes like a foreign body, corneal ulcer, abrasion, keratitis, glaucoma, or iritis are more likely to cause unilateral epiphora.

- Associated itching: itching may occur in the presence of allergies, which may be seasonal or caused by drops (glaucoma drops are a common culprit)

- Burning, discomfort on blinking, worse in the morning: may be associated with dry eye syndrome (keratitis sicca)

- Environmental factors: patients may complain of tearing when they are in a supermarket or store. Certain sprays used in such places can cause reactive epiphora

- Makeup: makeup products are made all over the world, and there have been reports of allergies to certain components of makeup products

- Eye medications: some eye drops like pilocarpine, phospholine iodide, and idoxuridine have been known to cause lacrimal obstruction

- History of chemotherapy: a number of chemotherapeutic drugs are known to cause canalicular scarring

- Radiation: radiation-induced punctal or canalicular scarring may be seen if radiation has been used in the periorbital region for basal cell carcinoma

- History of trauma to the nose: even remote injuries to the nose can result in fractures involving the nasolacrimal duct and may cause epiphora years later

- History of sinus disease or sinus or nasal surgery: trauma to the inferior turbinate or scarring at the inferior meatus of the nasolacrimal duct can be associated with prior sinus surgery. Sinus disease can cause mucosal thickening and obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct

- Previous eyelid surgery: functional or reconstructive eyelid surgery can result in eyelid malposition with associated epiphora, unilateral or bilateral. It is always wise to ask if patients have had previous eyelid or facial surgery, as the incisions may not always be discernible

- Previous lacrimal surgery or problems: some patients with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction may develop narrowing of the nasolacrimal systems years later. Similarly, there may be scarring from prior lacrimal surgery (canalicular scarring from probing, common canalicular scarring after dacryocystorhinostomy)

- Prior intracranial surgery or parotid surgery may suggest a prior facial nerve dysfunction

- Association with eating, chewing, or talking: when tearing is associated with any of these actions, it is usually unilateral and is associated with aberrant nerve regeneration of the seventh nerve ("crocodile tears")

- History of conjunctivitis or mucoid discharge. Conjunctivitis and mucoid discharge may occur in the presence of nasolacrimal duct obstruction. In these patients, gentle pressure on the lacrimal sac will yield mucous from each punctum

- Type of discharge, if present: a purulent discharge indicates bacterial infection; bloody may be associated with a lacrimal sac tumor

Examination

- An overall examination of the face should look for evidence of weakness: brow ptosis, upper lid retraction, or involuntary closing of the eyelids when chewing or blowing the cheek indicates prior facial nerve palsy with aberrant nerve regeneration.

- Evidence of prior trauma should be ascertained: specifically, look for nasal deviation and hypertelorism

- Inspect for evidence of prior lacrimal surgery (a DCR scar) or eyelid surgery

- Look for a mass in the medial canthal region. A mass above the medial canthal tendon may suggest an ethmoidal lesion. A mass below the tendon indicates a lacrimal sac condition

- Redness and tenderness over the lacrimal sac indicate dacryocystitis

- Pressure on the lacrimal sac, whether the swelling is present or not, may show egress of mucoid material through the puncta, indicating a mucocele

- If there is a firm or hard mass that is non-fluctuant, it may indicate a lacrimal sac tumor

- Examine the medial canthal region for a lacrimal fistula: it may show the flow of tears or mucous

Examination of the Eyelids

- Severe ptosis can result in "kissing puncta," whereby the natural position of the puncta is disturbed and affects the flow of tears

- Eyelid retraction of the upper or lower eyelids may be seen after eyelid surgery, thyroid disease, trauma, or solar elastosis

- Orbicularis function is examined by examining the blink and the squeezing of the eyelids. Weakness may be seen in facial palsy but also in conditions like Parkinson disease, myotonic dystrophy, and chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Prior surgery can also lead to local orbicularis weakness with a weak blink

- Examine the patient for evidence of lagophthalmos

- Laxity of the upper eyelids can cause imbrication syndrome, where the upper eyelid overlaps the lower eyelid. Similarly, with floppy eyelid syndrome, there will be excessive laxity of the upper eyelid, which is easily everted by applying upward pressure on the upper eyelid. There will be a follicular conjunctival fornix reaction as well, often with a mucoid discharge. The lower eyelids will demonstrate a similar laxity

- The lower eyelid should be examined. The normal lower eyelid sits snugly against the inferior limbus of the cornea, with the lateral canthal attachment about 1.5 mm higher than the medial canthal attachment. Any overt retraction, ectropion, or entropion should be noted. A distraction test is performed where the lower eyelid is pulled away from the globe: the normal lower eyelid will not distract more than 8 mm on average. The "snap back" test is then performed by pulling the lower eyelid down and releasing it. A normal eyelid will "snap" back promptly. Any delay in the return of the eyelid against the globe or if the eyelid remains distracted from the globe can indicate orbicularis weakness or laxity of the medial or lateral canthal tendons.

- The eyelid margin should be examined under the biomicroscope to look for trichiasis and distichiasis

- The punctal position is examined: the normal lower punctum sits snugly against the medial globe, and the posterior wall of the lower punctum should not be visible with the patient is looking straight ahead. The normal position of the lower punctum is just lateral to the plica semilunaris. The upper punctum tends to be 1 to 2 mm more medial.

- Entropion may be missed on cursory inspection. The patient is asked to squeeze the eyelids forcefully, followed by opening them. Entropion is usually revealed because the overriding orbicularis turns the lower tarsal plate inwards when the lids are squeezed. Early entropion will correct itself once the lids are opened, so it is important to observe the patient carefully immediately after the opening of the eyelids.

- If there is an inferior scleral show (lower eyelid retraction), there may be a gradient problem with the eyelids, and the tears will not be successfully pumped into the lower puncta.

- The presence of meibomian gland disease, blepharitis, and eyelid margin inflammation (acne rosacea) should be looked for as secondary epiphora may occur. Specifically, the lid margins are examined for telangiectasia (often seen in acne rosacea), plugging of meibomian orifices, scruff along the lashes, and evidence of Demodex on the lashes.

Examination of the Conjunctiva, Plica Semilunaris, and Caruncle

- The conjunctiva is examined for the presence of symblepharon. Symblepharon will be evident when the lower eyelid is pulled downwards, and the globe will be seen to move with the eyelid, or bands from the tarsal conjunctiva to the bulbar conjunctiva will be seen. Symblepharon may be seen in mucous membrane pemphigoid disease, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, chemical burns, prior conjunctival trauma, or surgery.

- The upper eyelid should be everted to examine the tarsal conjunctiva for scarring (trachoma, trauma, surgery)

- Upper eyelid trichiasis may indicate the presence of trachoma

- Conjunctivochalasis is the conjunctival laxity seen with exposure to the sun and thyroid disease. The excessively loose conjunctiva obstructs the lower punctum, thereby causing tearing. Similarly, in some patients, hypertrophy of the plica semilunaris can obstruct the punctum

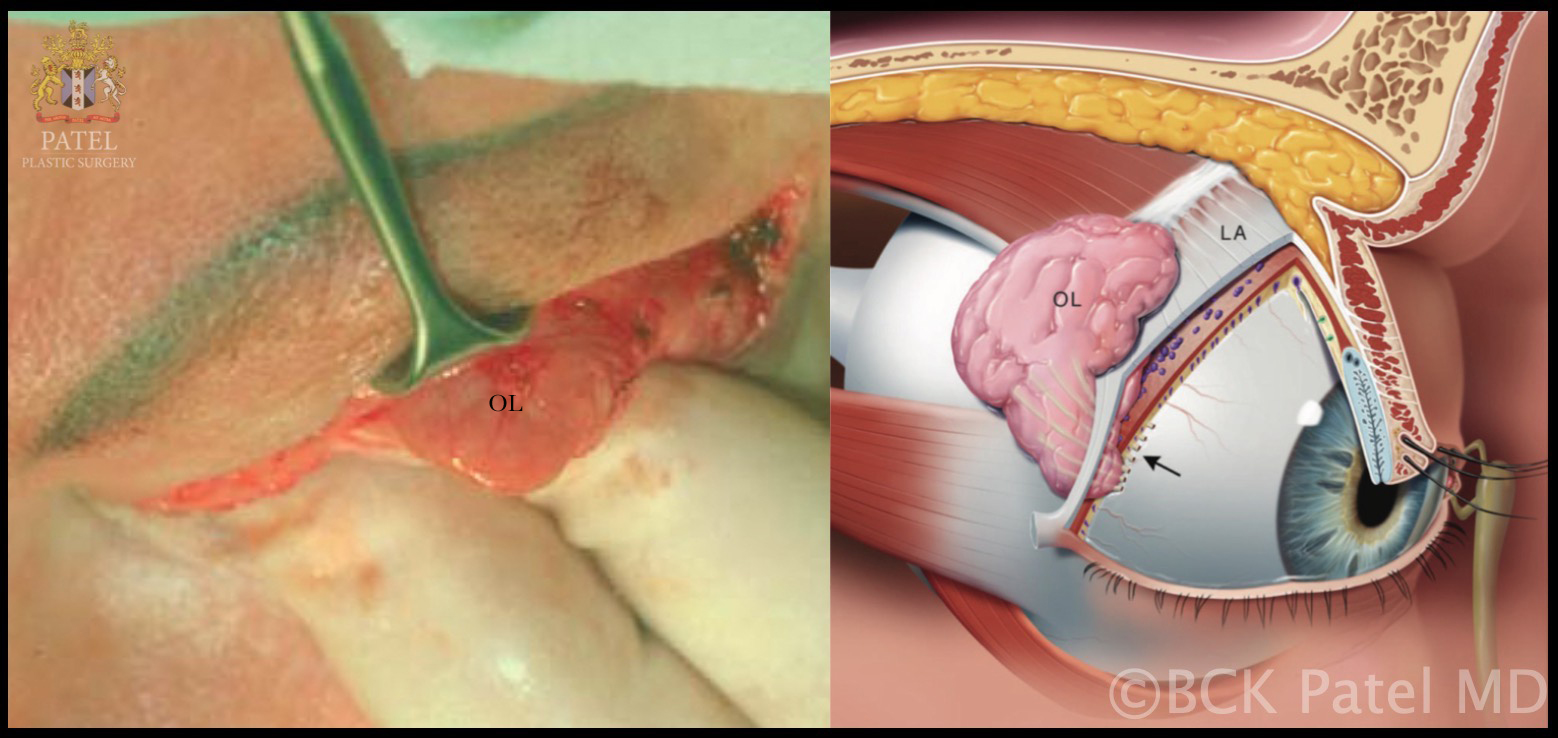

- A caruncle lesion or tumor may affect the apposition of the lower punctum to the globe. A caruncle tumor can obstruct the common canaliculus, which is only 2 mm from the posterior caruncle

Examination of the Cornea

- The cornea is examined for evidence of any corneal staining, scarring, pannus, or vascularization, which can indicate a chronic corneal disease

- Staining the cornea with fluorescein will show any corneal breakdown, although a corneal erosion may only be seen in the morning

- Staining of the cornea superiorly may indicate a foreign body that is frequently found just above the upper eyelid margin on the tarsal sulcus. The fluorescein staining will show vertical superior corneal stains.

- Trichiasis may show punctate staining of the cornea

Functional Nasolacrimal Obstruction

When a patient complains of tearing but the lacrimal outflow system is patent to irrigation, it is termed "functional epiphora" or "functional obstruction." This type of epiphora may be seen in patients who have had no trauma or surgery or may be seen after a dacryocystorhinostomy has been performed. Even if the lacrimal system appears to be open on irrigation, it is possible that there may be an anatomical narrowing of the lacrimal passage, either in the form of partial nasolacrimal duct obstruction (or narrowing), canalicular scarring, common canalicular scarring, or abnormal irregularities or "valves" which can be caused by scar tissue after dacryocystorhinostomy. To assess the true patency of the lacrimal system, it is necessary to perform a dacryocystogram (DCG).

When assessing a patient with epiphora, underlying orbital, sinus, or adnexal diseases should first be excluded. In particular, eyelid abnormalities (laxity, retraction, ectropion, entropion, trichiasis, etc.) and punctal stenosis or punctal malposition are properly assessed and excluded. Once this has been done, irrigation of the lacrimal system may be undertaken. If the irrigation shows patency but the patient has epiphora, a dacryocystogram will show any underlying anatomical narrowing or delay inflow.

If irrigation of the lacrimal system shows an obstruction, it is important to determine the type of obstruction. If there is a retrograde flow of fluid through the same canaliculus that is being irrigated, it indicates a canalicular obstruction. The level of obstruction can be determined by probing the canaliculus with a Bowman probe. If the fluid flows back through the opposite canaliculus, it indicates an obstruction in the nasolacrimal duct. As the canaliculi do not always open via a common canaliculus, common canalicular obstruction can be difficult to determine without a dacryocystogram. If there is a common canalicular obstruction, fluid will flow back out through the canaliculus being irrigated. This finding is seen more often after scarring at the common canaliculus seen in a failed dacryocystorhinostomy.

Dry Eye as a Cause of Epiphora

Multiple factors cause dry eyes, and there is also an inflammatory component. Two main types of dry eyes are recognized:

- Aqueous-deficiency subtype is caused by a decrease in lacrimal gland secretion

- Evaporative dry eye: excessive loss of tears by evaporation

Patients may present with burning, itching, blurry vision, and a sensation of scratchiness and discomfort that is often worse first thing in the morning. Patients with dry eyes will have tear film instability and tear hyperosmolarity. The normal tear balance in an eye comprises the following:

- Tear production by the lacrimal glands and the accessory lacrimal glands

- Normal blink to distribute the tears

- Evaporation of tears from the ocular surface

- Drainage of tears through the excretory lacrimal system

Tear film instability results in the loss of tears by evaporation, which stimulates corneal and conjunctival neurosensory receptors. This causes reflex tearing by stimulation of the lacrimal gland. Similarly, meibomian gland dysfunction can lead to abnormal lipids with a poor tear breakup time, increased evaporation, an increase in osmolarity, and an unstable tear film. This can cause increased growth of bacteria along the eyelid, it causes ocular surface inflammation and increased evaporation. Although Schirmer's test without topical anesthesia is used to measure reflex tearing, many patients with dry eyes will have normal Schirmer's test results. A tertiary referral oculoplastic practice found that dry eyes caused epiphora in 40% of their patients.[10] This is a higher percentage of patients than formerly thought. Because of travel, lifestyles, living in dry climates, increasing use of computers and screens, and prolonged close work, more patients are presenting with dry eyes. Although the evaporative loss of tears can cause reflex hypersecretion, many patients with dry eyes will have an inflammatory component. Therefore, besides the use of artificial tears and ointments, patients may need to have the inflammation controlled. Many patients will not have a tear volume deficiency but will demonstrate tear film instability. Meibomianitis and associated tear film instability have been found to be the main cause of tearing in as many as 20% of patients presenting with chronic epiphora.[11]

Epiphora in Facial Palsy

There are multiple causes of tearing in a patient with facial nerve dysfunction. If the tearing is worse when the patient chews, laughs, talks, or opens the mouth, then the cause is aberrant nerve regeneration: the facial nerve branches that would normally go to the parotid gland regenerate to supply the lacrimal gland. The tearing is sometimes called "crocodile tears" (Bogorad syndrome). This hyperlacrimation usually develops six months or more after the development of facial palsy. Although the reference to crocodiles crying when they eat their prey is thought to be more than a thousand years old, the first written documentation is found in "The Voyage and Travel of Sir John Mandeville," published in 1400: the book quotes "in that country by general plenty of crocodiles. These serpents slay men, and they eat them weeping." In mythology, it was thought that crocodiles wept tears while eating their prey to show sorrow. Physiologically, it is thought that the tearing occurs in crocodiles because of the pressure caused by the eating, which in turn forces air into the sinuses. This increase in forced air into the sinuses is thought to stimulate the lacrimal glands. Another explanation is that crocodiles are noisy eaters with huffing and other noises, which, in turn, causes the lacrimal glands to be stimulated.

Until recently, patients were offered various surgical procedures, including partial resection of the lacrimal gland, sphenopalatine ganglion block with alcohol, surgical denervation of the lacrimal gland, or vidian neurectomy. Vidian neurectomy gave a 50% success. The other procedures were unreliable and ran the risk of creating excessive dryness. Currently, injection of 2.5 to 4 units of botulinum toxin-A into the lacrimal gland gives relief for three to four months.[12] Botulinum toxin-A inhibits acetylcholine release and normally acts at the neuromuscular junction. In the lacrimal gland, the toxin stops transmission in the abnormal parasympathetic nerves.

In facial palsy, the orbicularis pump may be weakened with or without a frank lower eyelid laxity or ectropion and retraction. By examining the patient while they attempt tight closure, one can grade the orbicularis weakness (normal, mild, moderate, severe weakness). This is performed by attempting to open the squeezed eyelids. Most patients with facial nerve dysfunction will have some degree of orbicularis weakness and lower eyelid laxity with a frank retraction and/or ectropion. Inspection should show the lower eyelid sitting at the inferior limbus. Lower eyelid laxity examination is carried out with the distraction test and the snap-back test. Finally, many of these patients will have a sensory cause of tearing as well because of corneal exposure secondary to lagophthalmos. Bell phenomenon should always be assessed, and the degree of lagophthalmos documented. In our experience, epiphora in patients with facial weakness is almost always multifactorial. Simply tightening the lower eyelid may improve the lagophthalmos but rarely improves tearing unless the orbicularis weakness is only mild. Punctal eversion is also common because of the weakness of the orbicularis muscle. In many patients, the only way to substantially improve tearing is to insert a Lester Jones tube with a conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CDCR). When we place a Lester Jones tube, we always tighten the lower eyelid at the same time to improve tear flow, even if the pump is not improved much.

Evaluation

Tests performed in patients presenting with epiphora are classified as secretory and excretory tests and are discussed in the chapter "Epiphora: clinical testing." The tests performed include the following:

- Secretory clinical tests

- Examination of the tear film and cornea

- Tear break-up time

- The Schirmer's test

- Schirmer's 1 test

- Schirmer's test with anesthetic

- Schirmer's 2 test

- Excretory clinical tests

- The saccharin test

- Fluorescein dye disappearance test

- The Jones I test

- The Jones II test

- Probing of the canaliculi

- Nasal endoscopy

- Dacryocystography (DCG)

- Dacryoscintigraphy

- Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Dynamic magnetic resonance dacryocystography (MRDCG)

Treatment / Management

Appropriate management of epiphora depends on the etiology. For example, treatment of surface irritation with lubrication or eyelid repositioning surgery can decrease reflex tearing. Punctoplasty is performed to widen a tight punctum. Typically, one tip of a pair of scissors is introduced into the punctum to snip the punctum, creating a wider orifice. Balloon dacryoplasty (balloon dilation) introduces a balloon into the nasolacrimal system, which is inflated and then deflated and removed to push open the obstruction. The dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) surgical procedure creates a passage from the nasolacrimal sac to the middle meatus in the nose.[13] The conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CDCR) surgical procedure creates a passage from the conjunctiva to the middle meatus. The goal of both procedures is to create passages for tear drainage that bypass obstructions; the appropriate procedure is chosen based on the location of the obstruction. In patients for whom surgery is not an ideal option, such as some patients with malignant NLDO, injection of botulinum toxin into the lacrimal duct can provide relief.[14]

With a high rate of spontaneous resolution, “watchful waiting” is appropriate for many cases of pediatric epiphora. For congenital NLDO that does not resolve, probing with consideration of balloon dilation and/or silicone tube placement should be the first intervention. If the NLDO persists, DCR or CDCR can be performed.

Differential Diagnosis

The causes of adult epiphora may be summarized anatomically as follows:

- Punctum (35%)

- Punctal stenosis (involutional, drugs like topical idoxuridine, systemic 5-fluorouracil, docetaxel)

- Punctal membrane

- Punctal ectropion

- Punctal plugs

- Cauterized puncta

- Mechanical obstruction (conjunctivochalasis, caruncle)

- cicatrizing diseases and processes (Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pemphigoid disease, chemical injury, burns)

- Canaliculus (15%)

- Stenosis

- Infection (actinomyces)

- Scarring (herpes simplex)

- Foreign bodies (intracanalicular plugs like Herrick plugs, foreign bodies)

- Medications (anti-glaucoma drops, systemic drugs used for carcinoma like 5-fluorouracil, docetaxel)

- Nasolacrimal duct (24%)

- Primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Trauma to the nasolacrimal duct (rare)

- Lacrimal pump weakness (11%)

- Involutional eyelid laxity

- Seventh nerve palsy

- Floppy eyelid syndrome

- Pseudoepiphora (11%)

- Dry eye syndrome

- Eye inflammation (uveitis, scleritis, episcleritis)

- Nasal and sinus disease (4%)

- Polyps

- Nasal tumors

- Sinus surgery

- Allergic rhinitis

- Aberrant nerve regeneration (2%) - aberrant nerve regeneration after facial palsy

Epiphora in Children

Numerous conditions in children may cause epiphora:

- Dacryocystocele

- Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Punctal or canalicular agenesis

- Punctal occlusion

- Conjunctivitis

- Foreign body

- Keratitis

- Epiblepharon or entropion

- Ectropion

- Distichiasis

- Trichiasis

- Glaucoma

- Iritis

- Seventh nerve palsy

Prognosis

Epiphora is treatable in most patients with the appropriate diagnosis and treatment. A few patients are left with tearing without any underlying cause, and these are sometimes said to have "functional epiphora." Various treatments, including intubation, dacryocystorhinostomy, and injection of the lacrimal gland with botulinum toxin, have been used for patients with functional epiphora with varying success.

Complications

Complications of specific procedures performed for the management of epiphora are discussed under each procedure.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be instructed not to rub their eyes, which can stretch the periocular tissues and worsen surface irritation. Education on proper technique for lubricating the ocular surface is also important for many patients.

Pearls and Other Issues

- A detailed history is important.

- A sequential examination of each patient that presents with epiphora should be performed.

- With seasonal tearing, allergies are the most common cause, and surgical intervention is usually not necessary.

- With infants, it is best to wait until the child is a year old before irrigating and probing the nasolacrimal system, as the majority of them will improve spontaneously.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with tearing will present to opticians, optometrists, ophthalmologists, and family physicians. Each group needs to know the different causes of epiphora so that appropriate tests may be requested by referring patients to the appropriate specialist. [Level 4]