Continuing Education Activity

Dracunculiasis, also known as Guinea-worm disease is a parasitic disease caused by the nematode Dracunculus medinensis. The infection is transmitted to humans by drinking water contaminated with the small crustacean copepods (Cyclops) which contain the larvae of D. medinensis. Humans are the principal definitive host and Cyclops being the intermediate host. The disease is endemic to the rural and poorer areas of the world and is most common in African countries like Chad, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Mali. Efforts are underway towards global eradication of this disease. Due to its rarity in developed countries, this activity describes the interprofessional team's role in the assessment and treatment of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology for developing Dracunculus medinensis infection.

- Describe the epidemiology of Dracunculus medinensis.

- Outline the management considerations for patients with Dracunculus medinensis infection.

- Summarize the importance of improving care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to enhance delivery of care for patients affected by Dracunculus medinensis.

Introduction

Dracunculiasis, also known as Guinea-worm disease, is a parasitic disease caused by the nematode Dracunculus medinensis.[1] Infection is transmitted to humans by drinking water contaminated with the small crustacean copepods (Cyclops), containing the larvae of D. medinensis. Humans are the principal definitive host, and Cyclops being the intermediate host. The disease is endemic to the rural and poorer areas of the world and is most common in African countries like Chad, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Mali. Efforts are underway towards the global eradication of this disease.[2]

Mature female worms can measure up to 1 meter in length and are 1 to 2 mm wide. Male worms measure 15 to 40mm in length and are 0.4 mm wide.[3]

Etiology

Dracunculiasis is caused by Dracunculus medinensis which is transmitted to humans by drinking unsafe water containing small crustacean copepods (Cyclops) containing the larvae of D. medinensis. Humans are the principal definitive host, and Cyclops is the intermediate host.

Epidemiology

The disease is endemic to the rural and more deprived areas of the world and is most common in African countries like Chad, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and Mali. Guinea worm affects rural area population groups whose livelihood depends on subsistence agriculture. The disease can occur in any age group but frequently presents in young adults between 15 to 45 years. Men and women are equally affected. Transmission of the disease depends on seasonal variation and usually occurs during the rainy season or dry season.

Estimates are that around 48 million people were affected by this disease in Africa, the Middle East, and India in the 1940s. Approximately 3.5 million cases were reported annually in the mid-1980s. Since the start of the Guinea Worm Eradication Program in the 1980s, the number of dracunculiasis cases have significantly decreased and is now on the verge of being eradicated.[4][5] Recent World Health Organization (WHO) reports from October 2018 state that only a few cases have been reports in Chad, South Sudan, and Angola.[6] The goal is to eradicate this disease from the world by the year 2020.[7][8]

Pathophysiology

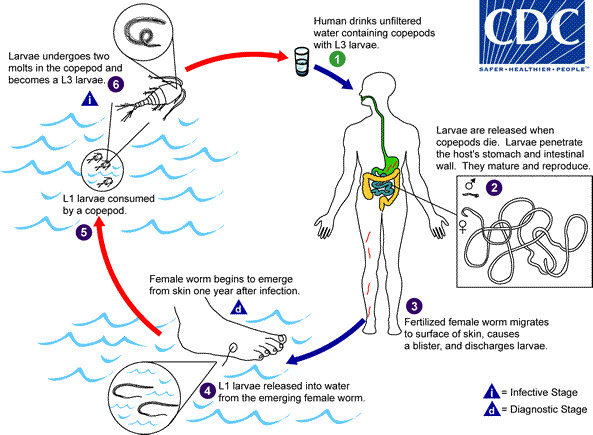

After ingestion of cyclops contaminated water, infected larvae released in the stomach penetrate the mucosa of the stomach and intestinal wall and migrate into the connective tissue. The larvae then mature into adult worms. After maturation and impregnation of the female worms, the male worms die. Female worms fully mature after 9 to 14 months and can measure up to 1 meter in length. Worms migrate through the subcutaneous tissue. Approximately after one year of infection, the female worms are attracted to the cooler surface of the skin and emerge from the skin, usually the feet. Before emerging, they form a painful blister at the skin site. Patients usually place or soak their legs in cold water to get relief from the symptoms, and this causes the worm to break from the blister and emerge from the skin. This stage causes itching and pain at the local skin site. During this time, the 1st stage larvae are released into the water and are ingested by the Cyclops and undergo two molts to develop into the 3rd stage larvae. Ingestion of Cyclops with 3rd stage larvae contaminated water by humans starts the lifecycle again.

An alternative life cycle was proposed recently involving dogs and fish.[9] After eating raw fish containing guinea worm larvae, dogs can get infected. By eating raw fish, humans can get infected; this reported alternative cycle had made the eradication of the disease more challenging, especially in Chad.[10][11]

History and Physical

Patients are usually asymptomatic for approximately one year after infection. Skin erythema and tenderness can present at the site of the emergence of the worm. When the adult worm emerges from the skin, it can cause blistering and ulceration, edema, pruritus at the location where it comes out. The worms usually emerge at the lower extremities, mainly the feet, in 80 to90% of the cases, although they can emerge from any part of the body. Sometimes more than one worm can emerge from the skin simultaneously. This painful process of emergence of the worm from the skin can last up to 8 weeks or more.

Systemic symptoms like fever, rash, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea can develop. An abscess can occur when the worms migrate to other tissue sites like the lung, pericardium, spinal cord. When the worms pass through the joints, they can cause joint pain and contractures. Occasionally sepsis can occur due to systemic infections. Cellulitis can occur. If the worm breaks before it is wholly extruded, this can lead to severe inflammatory reactions, pain, swelling, and cellulitis. In some cases, the worm can die before it emerges from the skin, and it can become calcified and encapsulated. This causes chronic recurrent pain and swelling.

Evaluation

Diagnosis is mainly by clinical presentation. Peripheral eosinophilia can be present in the blood work. Immunoglobulin G4 levels might be elevated.[12] If the worms die before they emerge from the skin, they may calcify and can be visible on x-rays.

Treatment / Management

Anti-inflammatory agents like aspirin and ibuprofen can help decrease pain and swelling. Diphenhydramine can treat the itching. Topical antibiotic cream or ointment is an option to prevent secondary bacterial infection at the site where the worm emerges. Systemic antibiotics may be required if cellulitis, sepsis, or abscess develops. Wound care is important.

Steps for worm extraction include: Exposing the affected body area to water facilitating the worm migration to the skin. The wound should then be cleaned. The worm should be slowly pulled out by applying gentle traction to the worm and should make sure to avoid breaking it. The worm is wrapped around a stick like a match stick or a gauze to apply tension and prevent it from going back inside. Topic antibiotics are used to avoid the development of secondary bacterial infections. Gauze and bandage are applied to the affected site. Anti-inflammatory agents like aspirin and ibuprofen can help decrease pain and swelling. All these steps are repeated daily, and it might take up to 8 weeks or more until the worm undergoes successful extraction. The infected patient should be careful to avoid wading as it can contaminate the water and spread of the disease.[13]

No medication is effective against guinea worm disease. Surgical extraction of the worm is the therapy in areas where facilities are available.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

Prognosis

Guinea worm disease is rarely fatal. The severe disease usually occurs due to secondary bacterial infections and sepsis. The condition can lead to temporary and permanent disability.[15] Prevention is the only effective method of contracting this disease.

Complications

Abscesses can occur when the worms migrate to other tissue sites like lung, pericardium, spinal cord. Occasionally sepsis can occur due to systemic infections and cellulitis. If the worm breaks before it is completely extruded from the skin, this can lead to severe inflammatory reaction, pain, swelling, and cellulitis. In some cases, the worm can die before it emerges from the skin and it can become calcified and encapsulated, this causes chronic recurrent pain and swelling. When the worms pass through the joints, it can cause joint pain and contractures.

Consultations

Infectious disease

Surgery consultation for surgical extraction of the worm

Deterrence and Patient Education

There is no medicine to treat dracunculiasis, and there is no vaccine to prevent this disease. Infected persons should strictly avoid any contact with drinking water sources to prevent contamination and the spread of the disease. Safe drinking water consumption should be encouraged.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Prevention and management of Guinea worm disease require an interprofessional effort involving the physicians, social workers, nurses, and epidemiologists. Community surveillance should be encouraged. Access to safe drinking water sources should be provided. the team must coordinate health education and behavioral change of the endemic communities. Treating contaminated water sources for vector control should be encouraged. An interprofessional team approach will lead to the best outcomes.[16]