Continuing Education Activity

Alopecia areata is a chronic, immune-mediated autoimmune disorder that affects hair follicles, nails, and, occasionally, the retinal pigment epithelium. This condition targets the anagen hair follicles of individuals and leads to hair loss without permanent damage to the follicles. The classic presentation of alopecia areata involves isolated, smooth, sudden, nonscarring, and patchy hair loss on the scalp or any area with hair growth. This condition arises from an autoimmune disruption in the normal hair cycle, resulting in the loss of immune privilege in the hair follicles.

Although many individuals experience spontaneous hair regrowth within 1 year, alopecia areata is a chronic condition characterized by recurring episodes of hair loss that require both psychological support and medical treatment. Various treatment options, such as corticosteroids, immunotherapy, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and topical solutions, are available to help manage the extent and duration of hair loss. This activity helps clinicians acquire proficiency in selecting and using diverse treatment modalities for patients with alopecia areata. This activity also provides pertinent knowledge to interprofessional healthcare teams to foster improved clinician-patient interactions by emphasizing mutual collaboration and holistic management. This approach leads to well-informed treatment decisions, enhanced patient outcomes, and improved quality of life for individuals with alopecia areata.

Objectives:

Identify the clinical manifestations and characteristic features of alopecia areata for accurate diagnosis.

Screen patients for signs and symptoms indicative of alopecia areata during routine examinations.

Implement evidence-based treatment strategies based on the severity and extent of hair loss in patients with alopecia areata.

Collaborate with interprofessional healthcare providers to coordinate care and provide holistic support to patients with alopecia areata by addressing both physical and psychosocial needs.

Introduction

Alopecia areata is a chronic, immune-mediated autoimmune disorder that affects hair follicles, nails, and, occasionally, the retinal pigment epithelium.[1] This condition targets the anagen hair follicles of individuals and leads to hair loss without permanent damage to the follicles. Alopecia areata arises from an autoimmune disruption in the normal hair cycle, resulting in the loss of immune privilege in the hair follicles.

Alopecia areata usually presents as localized patches of hair loss on the scalp, which develop over a few weeks (see Image. Alopecia Areata). The classic presentation of alopecia areata involves isolated, smooth, sudden, nonscarring, and patchy hair loss on the scalp or any area with hair growth.[2] Although many individuals experience spontaneous hair regrowth within 1 year, alopecia areata is a chronic condition characterized by recurring episodes of hair loss that require both psychological support and medical treatment. Various treatment options, such as corticosteroids, immunotherapy, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and topical solutions, are available to help manage the extent and duration of hair loss.

Etiology

The hair cycle consists of 3 phases—anagen, catagen, and telogen. During the anagen phase, active hair growth occurs, while the catagen phase involves the keratinization of the proximal end of the hair shaft. Subsequently, the hair follicle sheds and the remaining proximal end undergoes apoptosis. Telogen signifies the interval between the regression of the old follicle and the onset of the next anagen phase.

During the anagen phase, 6 stages of hair growth occur, with stage VI representing a fully formed anagen follicle. However, in individuals with alopecia areata, the hair follicles become arrested in stage III or IV, prematurely reverting to the catagen or telogen phase and leading to abrupt hair loss and hair regrowth deficiency.

Epidemiology

The lifetime risk of developing alopecia areata in the general population is estimated at 2%, with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 1000.[3][4] Although data indicate no demonstrable sex predilection, alopecia areata occurs more often among Asian, Black, and Hispanic patients. Alopecia areata affects children and adults, and the incidence rises steadily with age. The mean age at onset is 32 for males and 36 for females.[5]

Studies reveal that dermatologic and systemic conditions associated with alopecia areata include vitiligo, lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, thyroid disease, and allergic rhinitis.[6]

Patients with Down syndrome (trisomy 21, MIM #190685) and polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1 (MIM #240300) have an increased risk of developing alopecia areata.[7][8][9]

Pathophysiology

Specific critical body organs, including the eyes, central nervous system, testicles, fetus, and placenta, exhibit immune privilege, which is the ability to endure exposure to antigens without eliciting an inflammatory immune response. The loss of immune privilege within hair follicles and the subsequent immune dysregulation are central to the development of alopecia areata.[3][4]

Current evidence suggests that the cause of the condition is autoimmune, with a significant genetic contribution, further influenced by unknown environmental factors. Reported triggers include emotional or physical stress, vaccinations, viral infections, and medications.[1] These triggers initiate the loss of immune privilege by inhibiting the production of 2 anti-inflammatory cytokines—transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and α-melanocyte–stimulating hormone (α-MSH). In addition, they stimulate the expression of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA) on hair follicles. Subsequently, natural killer (NK) cells become activated, leading to the secretion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-15 (IL-15).

IFN-γ stimulates the expression of MHC-I proteins on hair follicle cells, revealing previously hidden antigens to T cells. Notably, IL-15 inhibits regulatory T cells. IFN-γ and IL-15 activate target immune cells via the JAK signal transducer and activator of the transcription (JAK-STAT) signaling pathway. As a result, inflammatory cells target the hair follicle matrix epithelium undergoing early cortical differentiation or anagen hair follicles, prematurely pushing them into the catagen or telogen phase.

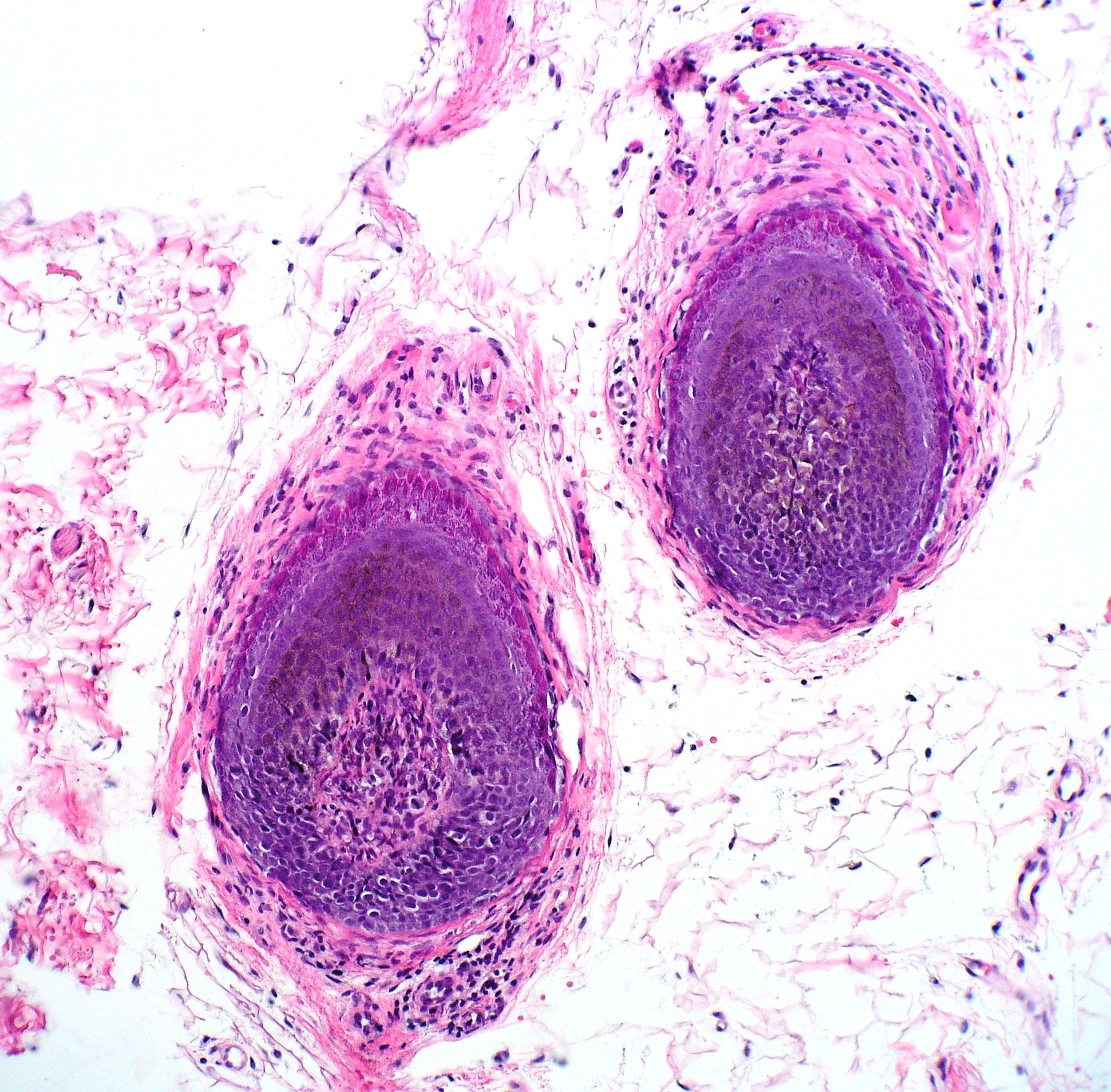

Histopathology

The histopathological observations in areas of acute active hair loss reveal a distinctive "bee-swarm pattern" characterized by dense lymphocytic infiltrates surrounding the bulbar region of anagen hair follicles (see Image. Alopecia Areata Biopsy).[1] This lymphocytic infiltrate comprises CD8+ T cells within the follicular epithelium and CD4+ T cells around the hair follicles.[10] Biopsies from regions affected by chronic alopecia reveal follicular miniaturization.

History and Physical

Alopecia areata usually presents as localized patches of hair loss on the scalp that emerge over a few weeks. However, this condition can also affect other areas, such as the beard, eyebrows, eyelashes, and extremities (see Image. Alopecia Areata Hair Loss). During active disease, exclamation-mark hairs, characterized by a narrower proximal end than the distal end, are commonly observed at the periphery of lesions and are a pathognomonic finding in patients with alopecia areata.[1] In a minority of cases, patients may progress to total hair loss on the scalp, known as alopecia areata totalis. Furthermore, some individuals may experience complete hair loss across the entire body, termed alopecia universalis.

The various patterns of alopecia areata are:

- Ophiasis pattern: Hair loss affecting the occipital region.

- Sisaipho (or ophiasis inversus) pattern: Hair loss involving the frontal, temporal, and parietal scalp but spares the occipital region.

- Diffuse pattern: Rapidly progressive and diffuse hair loss followed by regrowth within several months.[1]

A subset of patients may experience total hair loss on the scalp, known as alopecia totalis, or total hair loss across the entire body, including the eyelashes and eyebrows, termed alopecia universalis. For additional information regarding the diagnosis and management of alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis, please refer to StatPearls' companion topic, "Totalis Alopecia" https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/.

Approximately 10% to 15% of patients with alopecia areata experience nail involvement, characterized by fine nail pitting, trachyonychia, onychorrhexis, red spotting on the lunulae, onycholysis, and onychomadesis (see Image. Alopecia Areata Dystrophic Nails). White hair is often spared, initially giving patients the appearance of rapid greying. In addition, individuals with alopecia areata also have an elevated risk of developing conditions such as retinal detachment, retinal vein occlusion, and retinopathy.[11]

Evaluation

Alopecia areata is typically diagnosed clinically, relying on the patient's medical history and physical examination. Rapidly developing individual patches of alopecia on the skin, often accompanied by minimal erythema, should raise clinical suspicion. Dermoscopy serves as a valuable complementary diagnostic tool in confirming the diagnosis.[12][13]

Broken hairs, yellow dots, black dots, exclamation point hairs, and short vellus hairs indicate early regrowth.[14] The absence of hair follicles indicates cicatricial or scarring alopecia. Conducting a hair pull test can confirm active hair loss. Additionally, examination of the nails may reveal findings that support the diagnosis.

A skin biopsy from the periphery of an active hair loss patch may be beneficial if the diagnosis remains uncertain.[1] Although alopecia areata is associated with other autoimmune diseases, current evidence does not advocate for routine screening unless the patient's clinical history suggests their presence.[4]

Treatment / Management

Approximately 50% of patients will experience natural hair regrowth within 1 year without intervention, and some may decide not to seek treatment. For those who choose treatment, intralesional and topical corticosteroids are often the initial therapy for patchy alopecia areata.

Intralesional Corticosteroids

Triamcinolone acetonide, at concentrations ranging from 5 to 10 mg/mL and administered every 4 to 6 weeks on the scalp, stimulates localized regrowth in 60% to 67% of patients.[1] Clinicians typically use triamcinolone acetonide concentrations of 2.5 to 5 mg/mL to treat the eyebrows and beard in patients, and they can expect new hair growth within 6 to 8 weeks. Clinicians repeat injections until complete hair regrowth is achieved, while therapy discontinuation is recommended if no improvement is observed within 6 months. A comparative study among intralesional triamcinolone acetonide concentrations of 2.5 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL, and 10 mg/mL reveals similar hair regrowth rates irrespective of the concentration. However, the risk of cutaneous atrophy is more significant with the higher concentrations of 10 mg/mL triamcinolone.[15]

Patients typically receive approximately 0.1 mL of triamcinolone acetonide spaced 1 cm apart in the affected area. The dose of triamcinolone acetonide usually ranges around 20 mg per session on the scalp but should not exceed 40 mg to mitigate systemic adverse effects. Topical application of prilocaine or lidocaine cream 30 to 60 minutes before injections may be beneficial for patients seeking pain reduction.

Although intralesional betamethasone is a consideration for treatment, further studies are necessary to assess its efficacy.[16] Potential adverse effects of corticosteroids include localized skin atrophy, pain, telangiectasia, and depigmentation. Systemic adverse effects such as adrenal suppression or Cushing syndrome are rare. However, the use of intralesional corticosteroids on the face may lead to significant hypopigmentation in individuals with darkly pigmented skin.

Topical Corticosteroids

Betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream, lotion, or ointment is a potent topical glucocorticoid used to treat alopecia areata. Healthcare professionals typically reserve topical corticosteroids for children and patients who cannot tolerate numerous injections. Patients apply betamethasone to the affected area daily, extending 1 cm beyond the affected border. Clinicians discontinue topical corticosteroids if symptoms do not improve within 3 months. However, in cases where progress is noticeable, patients continue using betamethasone while gradually reducing the dosage. Betamethasone is applied without occlusion to reduce the risk of adverse effects. Using it under occlusion may increase the risk of potential adverse effects, which align with those associated with intralesional injections.

Immunotherapy and JAK Inhibitors

Patients with extensive disease, often characterized by more than 50% hair loss on the scalp, may explore treatment alternatives such as topical immunotherapy or oral JAK inhibitors to reduce the necessity of numerous injections associated with intralesional corticosteroids. Moreover, a retrospective study revealed the superior efficacy of topical immunotherapy compared to intralesional corticosteroids in patients with hair loss patches exceeding 50 cm².[17]

The choice between topical immunotherapy and JAK inhibitors depends on patient preference and availability. JAK inhibitors are easier to apply but carry the risk of systemic adverse effects. On the other hand, topical immunotherapy requires careful application and may induce discomfort and cutaneous adverse effects.

A potent contact allergen, such as diphenylcyclopropenone (DPCP) or squaric acid dibutyl ester (SADBE), can be applied weekly to the scalp to stimulate hair regrowth. Clinicians obtain both these allergens from compounding pharmacies. Treatment begins by applying a small patch at full concentration to sensitize the patient. After 1 to 2 weeks, complete treatment begins with diluted solution concentrations, gradually increasing the concentration weekly. The dose that causes mild dermatitis is the dose used for future doses. Patients may titrate up to a maximum dose of 2%.

Following treatment initiation, clinicians typically assess hair growth approximately 3 months later. A recent meta-analysis examining clinical outcomes of contact immunotherapy for alopecia areata indicates that 74.6% of patients with patchy alopecia experience hair regrowth, compared to 54.4% of patients with alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. Among patients who receive maintenance treatment, the recurrence rate is 38.2%, contrasting with 49% among those who do not receive maintenance treatment.[18]

Oral baricitinib, a selective and reversible JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, treats alopecia areata by suppressing the activation of T lymphocytes. Patients typically require ongoing therapy to sustain the benefits achieved. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a boxed warning for JAK inhibitors, cautioning about the risk of severe infections, mortality, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis. Initial dosing is 2 mg/d with an increase to 4 mg/d if the response is inadequate after 3 months. Patients with severe symptoms may start at the 4 mg/d dose. Upon achieving an adequate response, clinicians reduce the dose to 2 mg. Therapy is discontinued if no improvement is observed after 6 months.

Oral ritlecitinib, an inhibitor of JAK3 and the tyrosine kinase expressed in the hepatocellular carcinoma kinase family, is approved by the FDA for patients aged 12 and older with alopecia areata. Similar to baricitinib, continued use is likely necessary to maintain the effects. The initial dose is 50 mg/d. Potential adverse effects are increased risk for severe infection, death, malignancy, lymphoproliferative disorders, major adverse cardiovascular events, thromboembolic events, and hematologic, hepatic, and creatine phosphokinase laboratory abnormalities.

Additional Therapies

Various additional therapies are available for patients with refractory disease or who cannot receive first-line therapies, including topical or oral minoxidil, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, platelet-rich plasma, topical anthralin, excimer laser, and ultraviolet A photochemotherapy (PUVA).[19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Systemic glucocorticoids may promote hair growth, but their adverse effects limit their use. However, patients experiencing rapid and extensive hair loss may find oral glucocorticoids beneficial. Furthermore, relapse occurs within 1 year in approximately one-third of responsive patients, with the likelihood of relapses increasing over time.[1][25] Ongoing investigational treatments include recombinant IL-2, hydroxychloroquine, and simvastatin with ezetimibe.[21][22][23][24][25]

Currently, effective topical therapies for eyelashes are lacking. However, some individuals may observe improvement with systemic therapy. Patients may explore the option of using false eyelashes. Other cosmetic alternatives include tattooed eyebrows, wigs, hairpieces, and head shaving.

Alopecia areata can be distressing and may result in anxiety and depression for some individuals. Consulting with a psychologist or psychiatric provider may be necessary in such cases.

Differential Diagnosis

Specific medical conditions that may be mistaken for alopecia areata include androgenetic alopecia, traction alopecia, trichotillomania, tinea capitis, secondary syphilis, aplasia cutis, and temporal triangular alopecia.

Prognosis

Individuals with alopecia areata maintain the potential for hair regrowth, as 34% to 50% of those with patchy hair loss experience spontaneous recovery within 1 year. However, most patients will encounter recurrence, and less than 10% will recover completely.[1] Approximately 10% of patients with patchy disease will develop alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis.

Prognostic factors, including the extent of hair loss and age at diagnosis, play a crucial role. A diagnosis in childhood and an ophiasis distribution suggest an unfavorable prognosis.[4] Furthermore, a family history of alopecia areata, severe disease, duration of more than 1 year, nail dystrophy, atopy, or concurrent autoimmune disease may indicate a poor prognosis.[3][26][27]

Complications

Some potential complications of alopecia areata include the following:

-

Depression and anxiety, permanent hair loss, recurrence, nail abnormalities, sunburn, and skin damage.

-

Unpredictable pattern, texture, and rate of hair regrowth.

-

Increased risk of concurrent dermatologic and systemic illnesses such as thyroid disease, vitiligo, psoriasis, lupus erythematosus, and atopic dermatitis.[28][29]

-

Skin atrophy, hypopigmentation, infections, malignancy, dermatitis, and thrombosis due to adverse effects of medication.

- A 3-fold higher risk of developing retinal diseases such as retinal detachment, retinal vascular occlusion, and retinopathy.[11]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Alopecia areata is an autoimmune condition characterized by sudden and patchy hair loss, which can occur on any part of the body. This condition arises from a malfunction in the body's natural defense mechanisms. Patients should find encouragement in knowing that the hair follicles are not permanently damaged, suggesting that regrowth is possible, and nearly half of affected individuals experience spontaneous hair regrowth within 1 year.

Although alopecia areata is not a life-threatening condition, its psychosocial impact can be significant. Seeking emotional support from a psychologist, psychiatric provider, or support group can be beneficial. In addition, resources are available through the National Alopecia Areata Foundation's website at https://www.naaf.org/.

Currently, alopecia areata lacks a permanent cure, and many individuals with this condition will experience recurring episodes of hair loss throughout their lives. However, not all affected individuals require or desire treatment. For those who do, multiple treatment options are available.

Cosmetic choices may help manage the appearance of hair loss:

- High-quality wigs and hairpieces offer a natural appearance and boost confidence.

- False eyelashes can enhance the eye area for individuals experiencing eyelash involvement.

- Tattooed eyebrows offer a permanent solution for addressing eyebrow hair loss.

Various medications are available for managing alopecia areata, some of which are listed below.

- Topical or injected corticosteroids reduce inflammation and promote hair regrowth.

- Topical immunotherapy stimulates the immune system to facilitate hair growth.

- Anthralin application in the affected areas can promote hair regrowth.

- Minoxidil, whether taken orally or applied topically, may occasionally aid hair regrowth.

- Oral JAK inhibitors are a newer treatment option prescribed for more severe cases of alopecia areata.

Alopecia areata is commonly associated with other dermatologic and systemic diseases. Patients must be educated on the symptoms of thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis and report any symptoms they experience. Healthcare professionals treating patients with Down syndrome and polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1 should be vigilant due to the heightened risk of alopecia areata and should monitor for any signs of patchy hair loss.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Comprehensive care for patients with alopecia areata involves addressing both the psychosocial and physical aspects, along with monitoring for associated illnesses. Various healthcare specialties, including primary care, dermatology, rheumatology, and endocrinology, frequently encounter patients with alopecia areata. To effectively care for these individuals, healthcare professionals must possess essential knowledge for diagnosis and management, understand potential treatment adverse effects, and recognize the psychosocial impact of alopecia areata. In addition, clinicians must remain vigilant for associated dermatologic and systemic illnesses, ensuring seamless interprofessional communication of specialty opinions and relevant test results.

A strategic treatment plan is crucial to optimize outcomes and minimize adverse effects. Clinicians play a vital role in helping patients understand that hair regrowth may not occur rapidly, providing both medical and psychosocial support. Establishing realistic expectations through shared decision-making between patients and clinicians is crucial in determining whether to pursue treatment. Involving a psychologist or psychiatric healthcare professional can play a crucial role in alleviating symptoms of depression and anxiety among individuals with alopecia areata.[30]

Providing resources for additional information and community support can help mitigate feelings of isolation. By endorsing an interprofessional team centered around skill, communication, strategy, and responsibility, healthcare professionals can deliver optimal patient-centered care to those affected by alopecia areata. Enhancing the comprehensive knowledge of healthcare professionals, including understanding the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment strategies, while improving skills in patient communication, expectations, and emotional support, will elevate clinicians' capacity to deliver optimal care for patients with alopecia areata.