Continuing Education Activity

Sports-related traumatic brain injury (TBI) has become increasingly popular in the scientific literature over the past few decades. However, the first mention of such a subject in the literature occurred in the 1920s with reference to the “punch drunk” syndrome of boxers. About a decade later, the term “dementia pugilistica,” which literally means “boxer’s dementia,” was born. The now more commonly used term chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) was coined later in the 1940s. This term has gained favor in the modern literature because it is now understood that exposure to TBI from any sport or source increases the risk for a neurodegenerative disease first described in boxers. While there has been some effort to distinguish dementia pugilistica from CTE or to classify dementia pugilistica as a subtype of CTE, the two are now widely considered to be equivalent. Thus, while the term dementia pugilistica is certainly of historical significance, this activity will focus on the neurodegenerative disease resulting from (mainly sports-related) TBI that is now most commonly referred to as CTE. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of sports-related traumatic brain injury and addresses the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Outline the comparisons of sports-related brain injury vs. chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

- Describe the neurodegenerative diseases resulting associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

- Review possible treatment options for chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

- Summarize the medical team involvement in diagnosis, treatment, and education regarding chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Introduction

Sports-related traumatic brain injury (TBI) has become increasingly popular in the scientific literature over the past few decades.[1]However, the first mention of such a subject in the literature occurred in the 1920s with reference to the “punch drunk” syndrome of boxers. About a decade later, the term “dementia pugilistica,” which literally means “boxer’s dementia,” was born. The now more commonly used term chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) was coined later in the 1940s.[2]This term has gained favor in the modern literature because it is now understood that exposure to TBI from any sport or source increases the risk for neurodegenerative disease first described in boxers. While there has been some effort to distinguish dementia pugilistica from CTE or to classify dementia pugilistica as a subtype of CTE, the two are now widely considered to be equivalent.[3]Thus, while the term dementia pugilistica is certainly of historical significance, this article will focus on the neurodegenerative disease resulting from (mainly sports-related) TBI that is now most commonly referred to as CTE.

Etiology

There is a clear environmental etiology to CTE: the repetitive closed-head injury that occurs due to years of playing a variety of contact sports such as boxing, football, rugby, hockey, or lacrosse. Taking into account the similarities that have been noted between CTE and Alzheimer's disease (AD), another neurodegenerative process, there has been speculation that the two share similar genetic risk factors. The gene that has gained the most attention is the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) e4 allele, which may be involved in the inhibition of neuronal growth following brain injury. In addition to genetic risk factors, it has also been hypothesized that various psychosocial factors, the age at which an individual begins playing contact sports, and even exposure to performance-enhancing drugs may all play a role in the development of a later neurodegenerative disease.[2]

Epidemiology

Almost two-thirds of the American population is involved in some form of organized sport, and it is estimated that one and a half to four million concussions occur due to sport each year in the United States. It has been estimated that approximately 17% of people with a repetitive concussion or mild TBI develop CTE. As of a review of pathologically confirmed cases of CTE in 2009, 90% were found in athletes, 85% of those athletes were boxers, and 11% were football players. However, the understanding of the epidemiology of CTE continues to evolve as more postmortem data become available.[4]

Pathophysiology

At a microscopic level, the neurons, glia, and blood vessels of the brain are stretched when imperiled by rapid acceleration, deceleration, and rotational forces. More specifically, it is believed that axonal injury, micro-hemorrhage with subsequent loss of blood-brain barrier integrity, and the inflammatory cascade caused by activation of glial cells ultimately results in the deposition of both tau protein and neurofibrillary tangles in specific regions of the brain characteristic of CTE. Thus, CTE is considered a tauopathy along with Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases.[3]

Histopathology

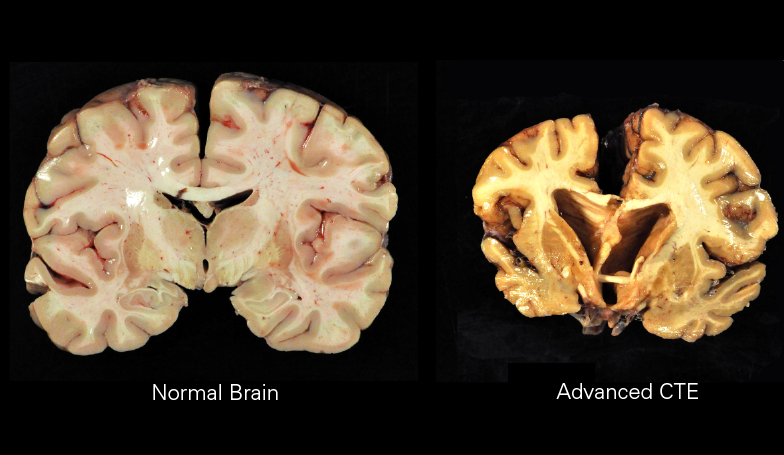

Macroscopically, CTE is characterized by diffuse atrophy of the brain including the cerebral cortex, mammillary bodies, corpus callosum, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellum. There is also ventricular dilation, fenestrated cavum septum pellucidum, as well as pallor of the locus coeruleus and substantia nigra. Histologically, there are tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles and astrocytic tangles preferentially deposited in the sulcal depths, periventricular areas, superficial cortex, around small vessels, and in subpial areas. It is this characteristic distribution that enables CTE to be distinguished histopathologically from other tauopathies.[1]

History and Physical

As the histopathologic diagnosis of CTE is made posthumously, clinical features of CTE have been garnered from retrospective case studies and interviews with family members of those diagnosed with the disease. Behavioral disturbances include aggression, explosivity, and impulsivity. Mood disturbances include anxiety, apathy, depression, lability, mania, and suicidality. Cognitive impairments include poor attention and concentration, dementia, executive impairment, and memory deficits. Motor deficits can include ataxia, gait disturbance, and parkinsonism.[5]

Evaluation

There are currently no biomarkers available for the diagnosis of CTE, and definitive diagnosis is made purely on postmortem neuropathological evaluation. While significant decreases in cerebrospinal fluid ApoE and amyloid beta have been found after TBI, there, unfortunately, have been no such studies to confirm if this is true with CTE. Therefore, fluid biomarkers may be a potential method of diagnosing CTE in the future. There is also hope that neuroimaging with functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging, volumetric MRI, and positron emission tomography can be added to fluid biomarkers for improved diagnosis of CTE.[4]

Treatment / Management

There have been increasing efforts in organized team sports to decrease the number of concussions by creating stricter penalties for intentional blows to the head in addition to “return to play” guidelines. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence-based data as to the best method of monitoring an athlete’s neurological dysfunction following a concussion, and there is not a consensus on when return to play is appropriate. Most recommendations focus solely on the resolution of symptoms before allowing for a return to play and various neuropsychological tests have shown abnormalities in concussed athletes up to 5 weeks following injury. Therefore, it is possible that at least a month may be required before return to play as re-injury is much more likely to occur in the period immediately following a TBI.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute management of stroke

- Acute subdural hematoma in the ED

- Alzheimer disease imaging

- Anterior circulation stroke

- Epileptic and epileptiform encephalopathies

Staging

Four progressive pathologic stages of CTE have been described. Stage 1 is characterized by normal weight brains with isolated perivascular centers of p-tau, neurofibrillary tangles, neutrophil neurites, and astrocytic tangles located primarily in the sulcal depths, especially in the superior and dorsolateral frontal cortices. Stage 2 is also characterized by normal weight brains but more frequent deposition at the depths of the sulci and neurofibrillary tangles interspersed throughout superficial cortical layers in addition to the locus coeruleus and substantia innominata. Stage 3 indicates a reduction in brain weight with mild cerebral atrophy, ventricular dilation, septal abnormalities, depigmentation of the locus coeruleus and substantia nigra, thinning of the corpus callosum, and atrophy of the mammillary bodies, thalamus, and hypothalamus. Finally, stage 4 is characterized by significant reduction in brain weight due to widespread cerebral cortical atrophy of the medial temporal lobe, thalamus, hypothalamus, and mammillary bodies. Complete depigmentation of the locus coeruleus and substantia nigra is evident along with the marked axonal loss of subcortical white matter.[6]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Over the last 2 decades, the incidence of head injuries in sports have spiked and there is growing awareness that these injuries are not benign. All sports organizations, amateur and professionals, have now taken steps to prevent head injuries by recommending the use of helmets in certain contact sports.

There have been increasing efforts in organized team sports to decrease the number of concussions by creating stricter penalties for intentional blows to the head in addition to “return to play” guidelines. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence-based data as to the best method of monitoring an athlete’s neurological dysfunction following a concussion, and there is not a consensus on when return to play is appropriate. Most recommendations focus solely on the resolution of symptoms before allowing for a return to play and various neuropsychological tests have shown abnormalities in concussed athletes up to 5 weeks following injury. Therefore, it is possible that at least a month may be required before return to play as re-injury is much more likely to occur in the period immediately following a TBI.[4]

The primary care provider and the nurse practitioner must emphasize head safety during sports to all athletes. In addition, some athletes may require neuropsychological testing at regular intervals to ensure that there are no cognitive deficits.[7][8][9] More important the healthcare providers should fully examine the athlete with TBI before recommending a return to the field.