Continuing Education Activity

Plantar fibromatosis, also known as Ledderhose disease, is a benign proliferative foot disorder manifesting as fibrous overgrowth of the superficial plantar aponeurosis. Ledderhose disease is diagnosed by identifying nodules within the plantar fascia's central or medial bands. These nodules can vary in size from small pea-sized lumps to larger, more noticeable masses in the arch area. The disease is locally aggressive, leading to pain and swelling in the foot's medial, non-weight-bearing plantar surface. The exact cause of plantar fibromatosis is not fully understood, but a combination of genetic factors, trauma, plantar fascia injury, and medical conditions such as Dupuytren contracture is believed to give rise to this condition.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learner's competence when diagnosing and managing plantar fibromatosis. After participation, clinicians exhibit improved proficiency in recognizing early signs, understanding treatment complexities, and implementing evidence-based strategies, ultimately optimizing patient outcomes for this challenging condition.

Objectives:

Identify the risk factors for developing plantar fibromatosis.

Create a clinically guided diagnostic strategy for a patient with suspected plantar fibromatosis.

Develop an individualized management plan for a patient diagnosed with plantar fibromatosis.

Implement communication strategies to enhance collaboration within an interprofessional team caring for individuals with plantar fibromatosis, especially when formulating short- and long-term treatments to improve quality of life and outcomes.

Introduction

Plantar fibromatosis is a benign, fibroblastic, proliferative connective tissue disorder of the superficial plantar aponeurosis. This condition, also known as Ledderhose disease, belongs to a family of similar diseases, including Peyronie and Dupuytren diseases, first described in 1610 by Plater.[1] George Ledderhose, a German physician, initially described the disorder in 1897 after observing 50 patients with painful sole lesions.[2]

Ledderhose disease is diagnosed by identifying nodules within the central or medial plantar fascia bands. Patients with plantar fibromatosis often present with sole lumps, usually in the arch area. These masses may be singular or multiple and may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. Onset is slow, and patients usually present with pain and swelling in the medial, non-weight-bearing plantar foot surfaces after the disease becomes locally aggressive.[3]

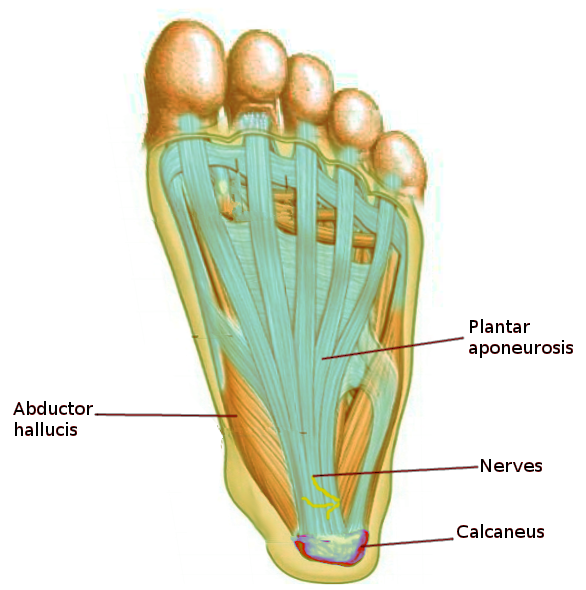

The plantar aponeurosis (plantar fascia) is a thick connective tissue band supporting the foot arch composed primarily of collagen fibers arranged in a dense, fibrous matrix. This fibrous structure extends from the heel bone (calcaneus) to the toe bases and helps absorb shock during walking and running (see Image. Plantar Aponeurosis). The plantar fascia is divided into 3 distinct bands: medial, central, and lateral. The medial band is the thickest and strongest portion, while the lateral band is thinner and less prominent. These bands work together to distribute forces evenly across the foot and maintain the arches during movement. Additionally, the plantar fascia is richly supplied with blood vessels and nerves, contributing to its ability to heal and transmit sensory information.

In plantar fibromatosis, nodules or fibrous growths may develop within the plantar fascia, typically in the foot's central or medial portion, leading to pain, discomfort, and limited mobility. Adjacent anatomical structures relevant to plantar fibromatosis include the foot muscles and tendons, such as the flexor digitorum brevis and abductor hallucis, which interact closely with the plantar fascia. Nerves supplying sensory information to the foot, such as the medial and lateral plantar nerves, and blood vessels providing oxygen and nutrients to the tissues are also important considerations in the anatomy of plantar fibromatosis.

Etiology

The exact etiology leading to plantar fibromatosis is unknown.[4] However, repetitive trauma, genetics, medications, alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, and other proliferative disorders appear to be associated with plantar fibromatosis.[5]

Epidemiology

Plantar fibromatosis is rare, affecting less than 200,000 people in the United States. The disorder typically presents in middle-aged patients, most commonly in the 4th and 5th decades of life. However, cases involving children as young as 9 months have been reported. The disease is twice as likely to occur in male than female individuals and has an incidence of bilateral foot involvement in approximately 25% of patients. Plantar fibromatosis is most common in patients with a history of diabetes, epilepsy, or alcohol use disorder. A familial inheritance pattern has been observed. Ledderhose disease shares a geographical similarity with Dupuytren hand contracture, as plantar fibromatosis is common in people of northern European descent.[6] Patients with Dupuytren disease requiring surgery for hand deformity are more likely to have Ledderhose disease.

Pathophysiology

Plantar fibromatosis has 3 stages. The 1st is a proliferative phase, where cell number increases in the plantar area. The 2nd stage is when the nodule forms. The 3rd stage produces soft tissue scarring and mild contracture in the plantar foot. The factors stimulating the hyperactive proliferating fibroblasts involved in the disease process are unknown. However, an increased release of growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factor-1, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and transforming growth factor-β, has been implicated. Increased interleukin-1-α and β have also been reported.

A genetic component is present in some cases. In a genome-wide association screen, 2 genetic variants were associated with plantar fibromatosis: one indel (chr5:118704153:D) and one single nucleotide polymorphism (rs62051384). Individuals with these variants may have an increased risk for plantar fibromatosis.[7]

Histopathology

Proliferating fibroblasts produce the pathologic plantar fascia nodules of plantar fibromatosis. These fibroblasts are found in areas surrounded by less cellular, modestly collagenous fascia. The cells are the same size, randomly arranged in a matrix, and have little vascular supply. The extracellular matrix and cytoskeleton have abundant fibronectin and myofibroblasts and a predominance of type III collagen.[8]

History and Physical

The classic plantar fibromatosis presentation is a slow-growing nodule in the foot's medial or central plantar aponeurosis about 0.5 to 3 cm in diameter. The nodule may be single or multiple. Smaller nodules can produce areas of local pressure or plantar distension. Progressive local invasion can lead to worsening pain, swelling, and weight-bearing and ambulating difficulties. Patients commonly present with intolerable foot sole pain after walking or standing for long periods. Direct pressure on the nodule or medial foot arch, eg, when barefoot on hard floors or wearing shoes with inflexible insoles, may exacerbate symptoms.

Physical examination of the foot and ankle should include visual assessment, soft tissue and bone palpation, and range of motion and gait evaluation. Plantar fibromas are typically visible or palpable. A few patients may present with toe contractures, particularly at the big toe.[9] Ledderhose disease can affect 15% of individuals with Dupuytren contracture. Thus, hand examination is also paramount.

Evaluation

Diagnosis is made based on the patient's history and physical exam. However, imaging and biopsy may be helpful for confirmation. Appropriate imaging studies include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound.

On MRI, a plantar fibroma may appear as a focal, round area or lobulated, disorganized tissue in the plantar fascia with low signal intensity or a signal similar to muscle.[10] Nodules appear well-defined, with signal intensity low on T1 images and low to moderate on T2 images. MRI with contrast, such as gadolinium, may enhance the nodules' intensity. MRI may be obtained for excision planning and identifying the plantar contractures' extent.

Ultrasound can show the nodule depth, size, and number. Nodules typically appear isoechoic and heterogenous on ultrasound. Hyperechoic septa may also be present. Vascular flow is not usually appreciable when using Doppler ultrasound.[11] Ultrasound is a time- and cost-efficient modality, providing physicians with a quick office diagnostic tool during the patient’s appointment.

X-rays may be obtained to rule out underlying bony pathology or soft tissue calcifications contributing to the symptoms. A biopsy may be utilized to rule out malignancy.[17]

Treatment / Management

Treatment Mainstays: Nonoperative Modalities

Multiple nonoperative treatments for plantar fibromatosis have been described. These modalities primarily focus on symptom reduction rather than nodule removal or disease progression prevention. The treatment mainstays are anti-inflammatories, physical therapy, and shoe wear or activity modifications. Adjunctive interventions are explained below.

Orthotics or pads

Patients with mild disease and minimal symptoms can place pads inside the shoe to offload the fibromatous foot parts. Increased internal shoe padding can also help alleviate symptoms like mild discomfort.[12] Carbon footplates or rocker bottom shoes may also decrease the stress across the plantar fascia.

Steroids

Few studies support steroid use in plantar fibromatosis, though these medications are proven beneficial in Dupuytren disease. Local steroid injection helps reduce plantar fascia node and strand size. Steroids are thought to decrease fibroblast activity and accelerate their apoptosis. These agents reduce VCAM1 expression, limiting proinflammatory cytokine production, inflammation, and nodule growth. Size reduction can occur over a few months. Complications due to steroid injections include fascial or tendon rupture, fat atrophy, and skin depigmentation.[13]

Collagenase

Clostridium histolyticum–derived collagenase is used to break down collagen. Collagenase injections have been used in treating Peyronie and Dupuytren diseases, but the evidence for this modality's effectiveness in plantar fibromatosis is limited.

Pentland et al described a case of a patient presenting with difficulty ambulating due to plantar fibroma pain. Monthly C histolyticum collagenase injections were performed off-label over 5 months. The patient was able to resume jogging 4 months following the last injection.

Meanwhile, Lehrman et al described a case report about treating a patient with recurrent plantar fibromas with collagenase injection.[14] The patient had failed conservative treatment and multiple surgical interventions before attempting collagenase therapy. Collagenase was injected into the fibroma in the following manner: a third of the solution was administered centrally, another third proximally, and the last third distally. The patient was brought back to the clinic 24 hours after the injection for fibroma fragmentation by plantar massage and passive range of motion exercises. The symptoms were reported to resolve at the last follow-up, 33 months after the intervention.

Verapamil

Verapamil is a calcium channel blocker commonly used as an antihypertensive. Verapamil has also been shown to promote collagenase activity and inhibit collagen production. Transdermal verapamil cream application and intralesional verapamil injection have demonstrated the ability to reduce fibroma size by 55% to 85%. Contact dermatitis is the most common complication of verapamil use.

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been used to treat multiple foot and ankle conditions, such as plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, delayed fracture healing, and wound healing issues. ESWT is a noninvasive intervention that acts by transmitting shock waves to the treated tissue and provoking a biological response. An animal study revealed that ESWT may induce free radicals to produce growth factors and promote angiogenesis and inflammation reduction. These actions combined result in soft tissue and bone healing.[15]

ESWT treats Dupuytren and Peyronie diseases effectively, but its utility in plantar fibromatosis treatment lacks evidence. ESWT seems to reduce pain and soften the nodules without reducing plantar nodule size.

Radiation therapy

Electron beam radiation is believed to decrease fibroblast activity by disrupting transforming growth factor-β production. This mechanism may slow disease progression and be most effective during the early stages of plantar fibromatosis.

Treatment guidelines recommend weekly radiation doses for a total of 6 weeks. One study showed a complete node resolution in 33.3% of cases and decreased node size in 54.5%. Radiation therapy's side effects include erythema and dry skin. The incidence of malignant skin transformation is unknown, as treated cases lack long-term follow-up.

Tamoxifen

Antiestrogen drug administration is still in the experimental phases as a possible treatment. Tamoxifen inhibits transforming growth factor-β expression, thus suppressing fibroblast proliferation and maturation and myofibroblast differentiation. Studies have demonstrated this antiestrogen's promise in Dupuytren contracture treatment, with up to 20% nodule size regression. However, no studies have examined the use of estrogen receptor-modulating agents in plantar fibromatosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Care should be taken to exclude other diagnoses if a foot arch mass is causing pain. The differential diagnosis of such a lesion includes plantar fasciitis, tarsal tunnel syndrome, calcaneus fracture, and tumor. Tumor types include leiomyoma, simple fibroma, liposarcoma, neurofibroma, rhabdomyosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and nodular fasciitis. Clinical history, imaging, and biopsy can differentiate between these conditions.

Surgical Oncology

The main surgical indications in plantar fibromatosis cases include conservative treatment refractoriness and compromise of daily activities, eg, when ambulation difficulty or inability to fit in the usual shoe size develops. Standard surgical strategy options include:

- Local excision, which entails removing the entire nodule; recurrence rate is 60% to 100%

- Wide excision, which involves removing the nodule with 2 cm margins; recurrence rate is up to 60%

- Complete fasciectomy, which removes the plantar fascia; recurrence rate is 25%

Sammarco and Mangone published an operative staging system taking into account the extent of plantar fascia involvement, skin adherence, and nodule depth.

- Grade 1: has a focal lesion but no extension and skin or muscle involvement

- Grade 2: involves multiple areas and can extend distally or proximally; has no skin or muscle encroachment

- Grade 3: involves multiple areas and can extend distally or proximally; has skin or muscle involvement

- Grade 4: encompasses multiple areas and can extend distally or proximally; involves both skin and muscle

Local recurrence is the most common concern in any surgical treatment. Some consider total or complete fasciectomy to be the primary plantar fibromatosis surgical treatment since it seems to have the lowest recurrence.[16]

A new endoscopic subtotal plantar fasciectomy technique has been described. This modality is indicated for recalcitrant fibromas. However, the treatment is contraindicated for nodules attaching superficially to the skin, invading deep foot musculature, or involving neurovasculature.[17] Compared to open excision, endoscopy is technically more challenging but results in better wound healing and minimal scarring due to the smaller incisions required.

Surgical planning should pay particular attention to incisions in weight-bearing areas. Longitudinal incisions can predispose the skin to hypertrophic scarring. Medial-to-midline transverse or zigzag incisions can put the skin at risk for necrosis due to plantar arterial supply disruption.[18]

Staging

Stages of Disease

Plantar fibromatosis development has the following stages:

- Proliferative phase: Increased fibroblast activity is observed.

- Active or involution phase: Fibroblast maturation, myofibroblast differentiation, and increased collagen production occur.

- Residual phase: Collagen and fibroblast maturation wane.

Sammarco and Mangone Classification

Severity may be evaluated using the following grading scheme:

- Grade 1: has a focal lesion but no extension and skin or muscle involvement

- Grade 2: involves multiple areas and can extend distally or proximally; has no skin or muscle encroachment

- Grade 3: involves multiple areas and can extend distally or proximally; has skin or muscle involvement

- Grade 4: encompasses multiple areas and can extend distally or proximally; involves both skin and muscle

Prognosis

Ledderhose disease may be treated during the first office visit with conservative therapy. Surgery is reserved for patients with lesions unresponsive to medical treatments or interfering with daily activities, such as wearing shoes or walking. Recurrence is high regardless if the treatment is nonoperative or operative.

Complications

Untreated plantar fibromatosis' main complication is chronic pain due to continued lesion growth. Additional complications include wound healing problems, hypertrophic scarring, and recurrence after treatment. However, plantar fibromas are benign tumors that do not usually have malignant potential.

Surgery, particularly local excision, has high recurrence rates. Recurrence is more frequent in patients with multiple lesions and positive family history. Besides recurrence, potential surgical complications include nerve entrapment and postoperative wound-related issues, such as dehiscence and painful scarring. A loss of medial longitudinal arch height has also been reported after subtotal fasciectomy. Plantar nerve damage can lead to numbness or neuroma formation.[18]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After surgical intervention, the patient remains non-weight-bearing on the surgical side until the incision heals approximately 3 weeks later. After healing, full weight-bearing and return to activity are allowed.

Consultations

Plantar fibromatosis consultation should include the following:

- Podiatry

- Orthopedics

- Physical Therapy

- Orthotists

Early intervention and treatment adherence can improve outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventive measures for plantar fibromatosis focus on minimizing risk factors and promoting foot health. These measures include the following:

- Keeping a healthy weight to reduce pressure on the feet

- Wearing properly fitting supportive footwear to distribute the load evenly and reduce strain on the plantar fascia

- Managing underlying conditions that may contribute to plantar fibromatosis development, such as diabetes mellitus and obesity

- Gradually increasing physical activity to allow the feet to adapt and limit the risk of overuse injuries

- Performing regular strengthening and stretching exercises to maintain foot stability and calf muscle and plantar fascia flexibility

- Regular foot care to avoid inflammatory foot conditions and prevent complications

Patients must be advised to consult a healthcare professional promptly for persistent foot pain.

Pearls and Other Issues

Plantar fibromatosis is a benign but highly recurrent connective tissue disorder involving the superficial plantar aponeurosis. The cause is unknown, but risk factors for developing plantar fibromatosis include genetics, plantar fascia injury, and medical conditions such as Dupuytren contracture and diabetes mellitus. The diagnosis of this condition is clinically based, although imaging and biopsy can help rule out serious conditions such as cancer.

Management depends on symptom severity and individual needs. Conservative measures such as orthotics, physical therapy, and steroid injections may be effective in managing mild to moderate cases. Surgical excision may be considered for larger or more symptomatic nodules, although recurrence rates can be high. Chronic pain and limited mobility are the most common complications of plantar fibromatosis. Prompt identification and appropriate management can help minimize these complications and improve quality of life for affected individuals. Collaborative care can help optimize treatment outcomes and address the needs of patients with this condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional care for patients with plantar fibromatosis may involve a team comprised of primary care physicians, podiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, pain specialists, orthotists, and nursing staff. Each team member functions according to the scope of their practice, working together to develop and implement a comprehensive care plan specific to individual needs.

Primary care physicians coordinate care with specialists, such as podiatrists and orthopedic surgeons, for specific interventions. Pain specialists may help manage chronic foot pain outpatient or provide anesthesia care during procedures. Physical therapists may assist with stretching the fascia and reducing the lesion size. Nursing may be involved in postoperative patient care. Orthotists help manage plantar fibromatosis by assessing foot mechanics and providing customized orthotic devices.

The key components of interprofessional care for plantar fibromatosis include comprehensive assessment, treatment planning, care coordination, patient education, and continuity of care. By taking advantage of the expertise and resources of multiple disciplines, interprofessional care can enhance the quality, safety, and effectiveness of treatment for patients with plantar fibromatosis, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of life.