Continuing Education Activity

Bladder cancer is any neoplasm that arises from the urinary bladder. It is the most common urinary tract neoplasm, with urothelial carcinoma (UC) being the most common histologic type. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of bladder cancer and highlights the interprofessional team's role in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the role that smoking, schistosomiasis, and occupational exposure to chemicals have in the etiology of bladder cancer.

Outline the TNM and clinical staging used in the evaluation of bladder cancer.

Identify UTI, painless gross hematuria, and irritative bladder symptoms as the early symptoms of bladder cancer.

Explain the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by bladder cancer.

Introduction

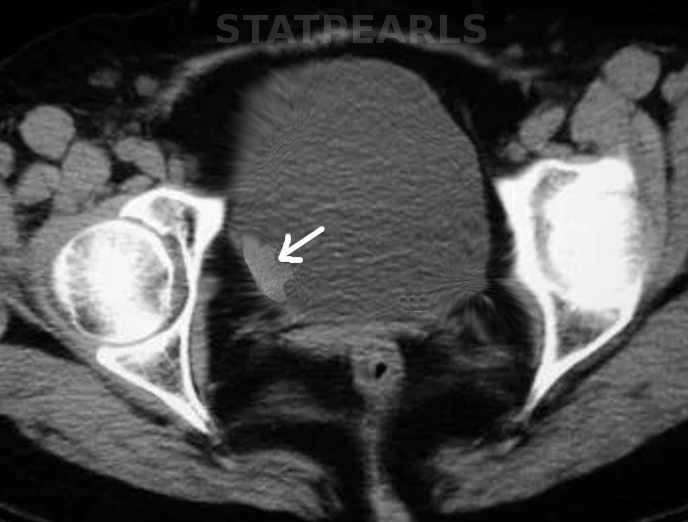

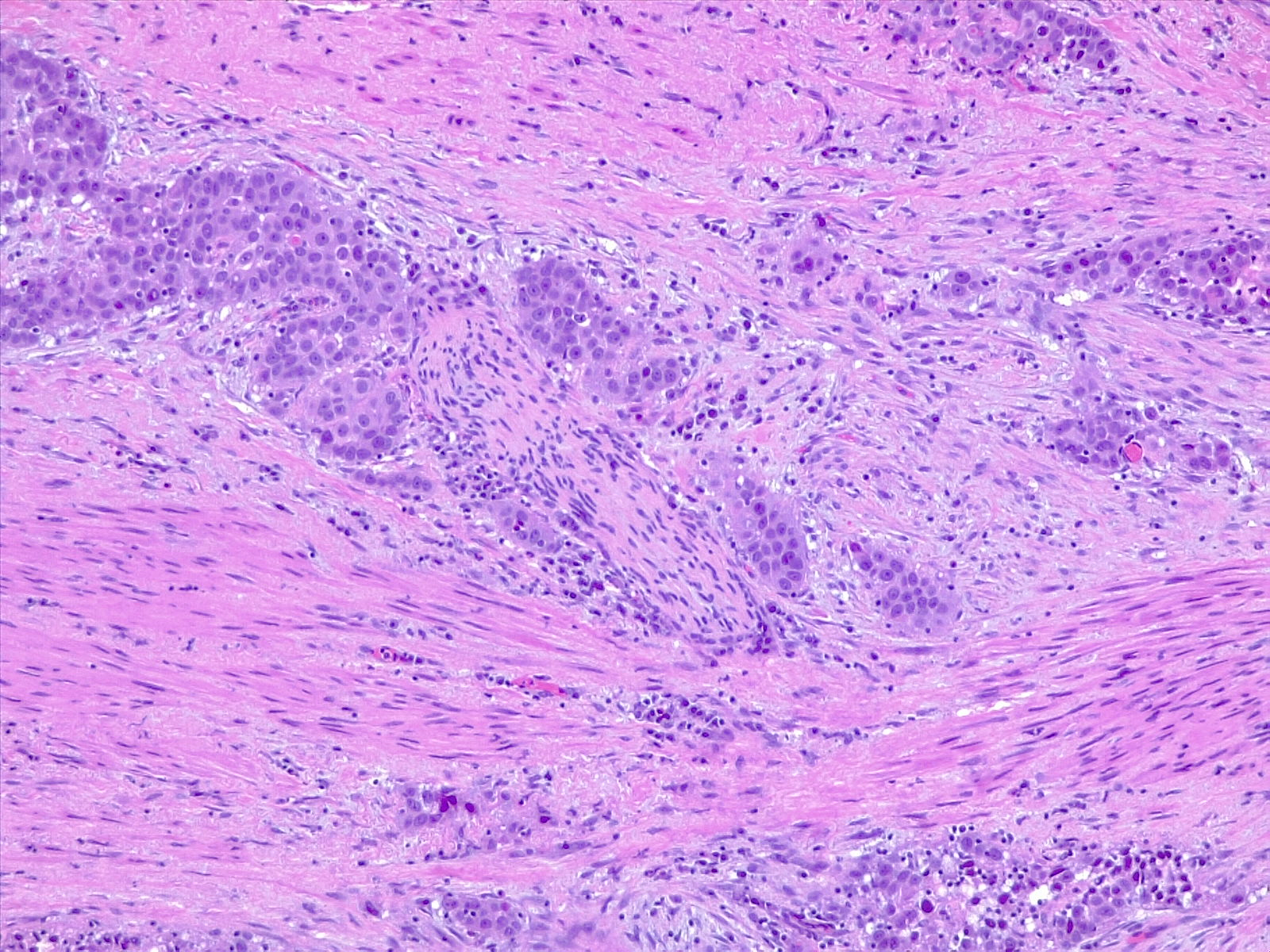

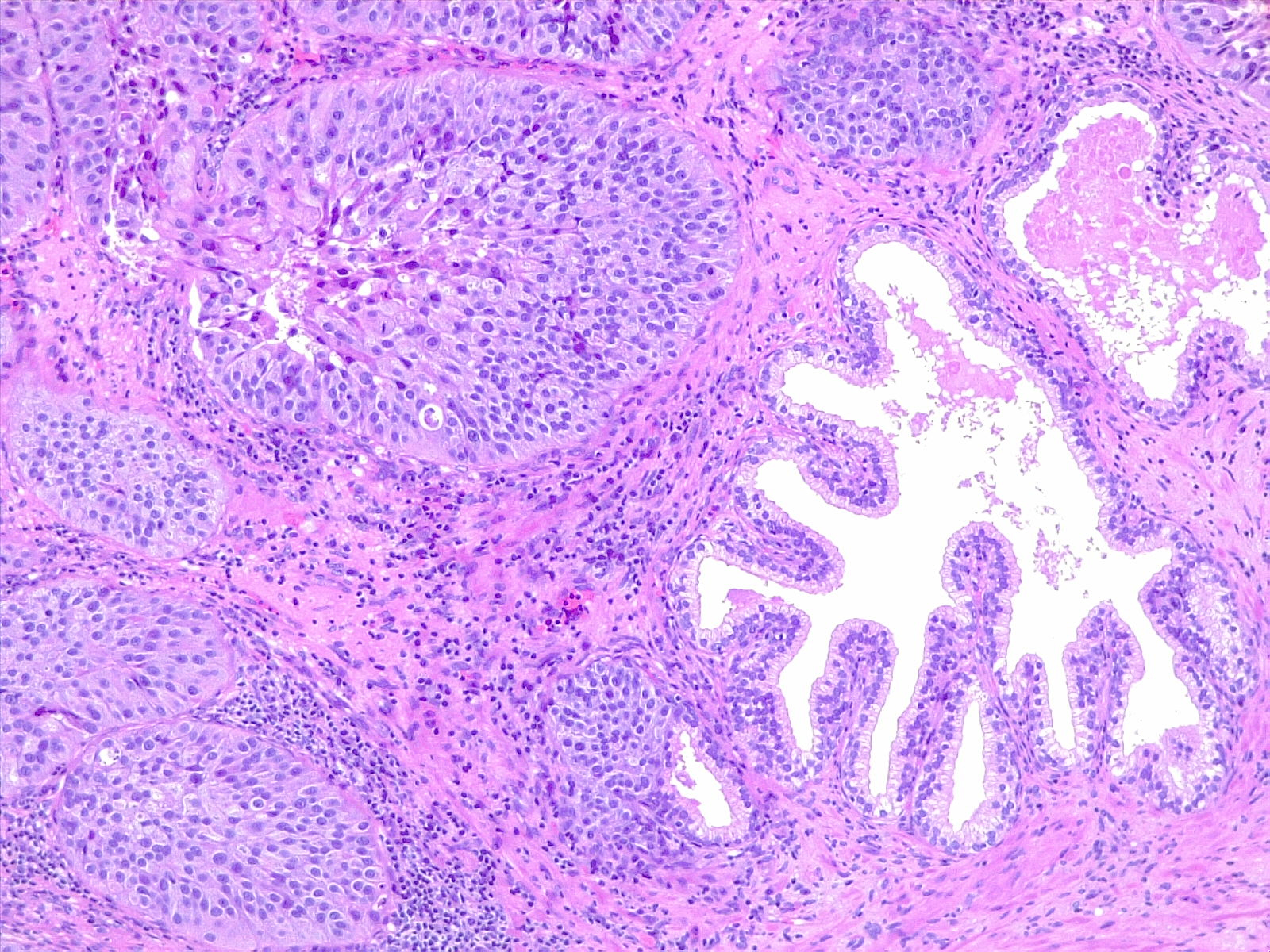

Bladder carcinoma (BC) is the most common neoplasm of the urinary system (see Image. Bladder Cancer). Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the most common histologic type of BC (approximately 90%). The definition of UC is the invasion of the basement membrane or lamina propria or deeper by neoplastic cells of urothelial origin. The WHO has replaced the old term transitional cell carcinoma with urothelial carcinoma. Invasion is referred to as ‘micro invasion’ when the depth of invasion is 2 mm or less (see Image. Urothelial Carcinoma, Perineural Invasion). The World Health Organization (2016) classifies bladder cancers based on differentiation as low grade (grade 1 and 2) or high grade (grade 3). The distinction between low-grade and high-grade urothelial disease has implications related to risk stratification and management of patients.

Etiology

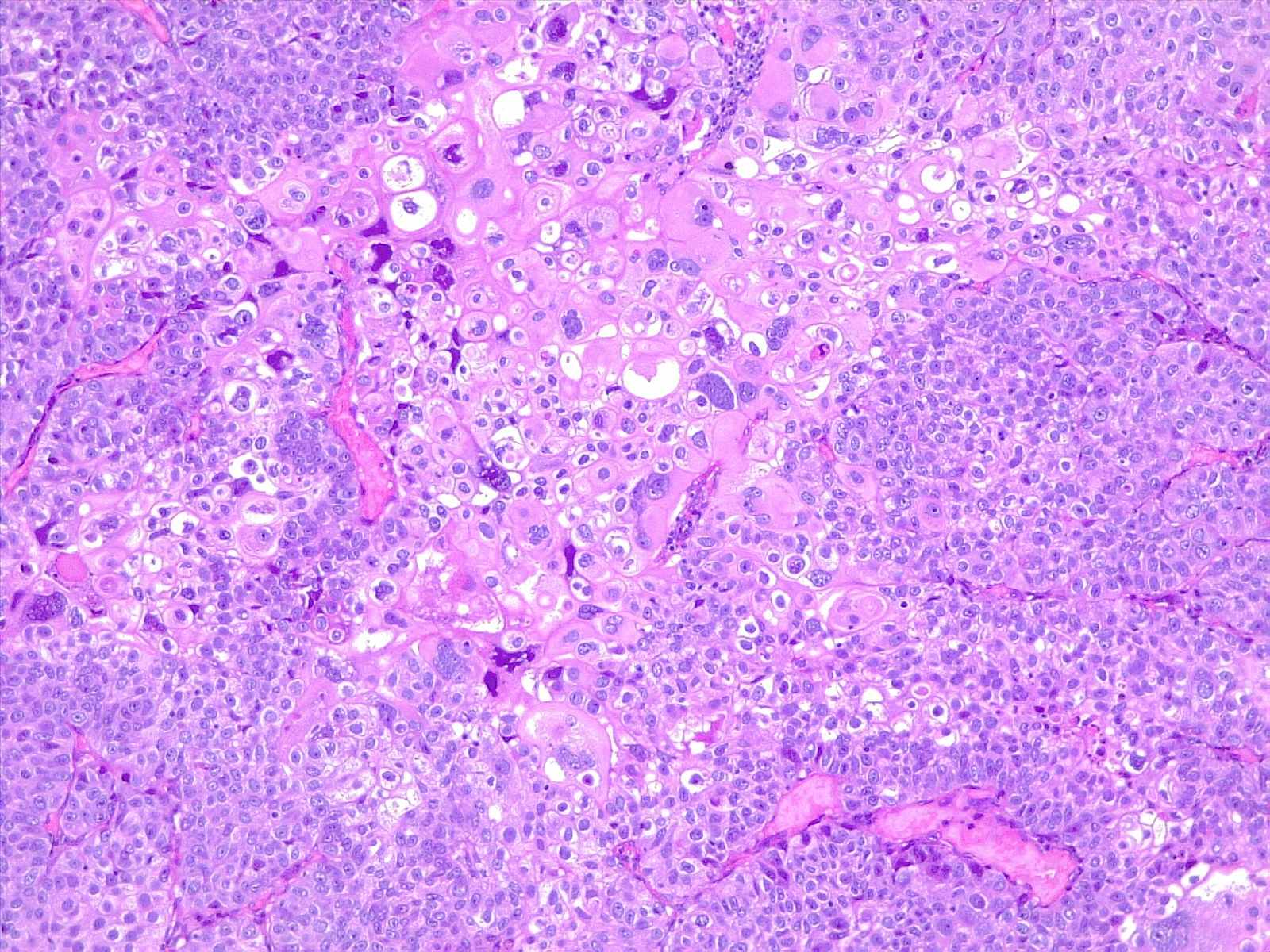

There are multiple known risk factors for BC. Important risk factors include smoking, schistosomiasis infection, and occupational exposure to certain chemicals.[1][2][3] Smoking is the most important risk factor for BC. The risk of BC in smokers is 2 to 6 fold that of non-smokers; the risk depends on smoking duration and intensity. In developing countries, schistosomiasis infection is an important cause of BC. Schistosoma haematobium ova embed in the bladder wall leading to irritation, chronic inflammation, squamous metaplasia, and dysplasia, with further progression leading to squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder (see Image. Poorly Differentiated Urothelial Carcinoma With Metaplastic Squamous Appearance). Occupational exposure to paint, rubber, petroleum products, and dyes correlate to BC. Chemicals associated with BC include arylamine dye, aniline dye, phenacetin (an analgesic), cyclophosphamide (a cytostatic drug), and arsenic.[4][5][6][7]

Epidemiology

Worldwide, BC is the seventh most common cancer. There were 79,030 new cases of BC and 16,870 deaths in the US because of BC in 2017. In the US, BC is the fourth most common cancer in males and the eighth in females. BC is twice as common in Caucasians compared to African Americans; the disease incidence increases with age. In the US, most BC is UC, and less than 5% are squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma. The incidence of BC is twice as high in developing countries compared to developed countries. In developing countries, most BCs are squamous cell carcinoma and correlate with endemic schistosomiasis.[8][9][10]

Pathophysiology

UC develops via two distinct pathways, the first relates to papillary lesions, and the second relates to flat lesions. Copy number alterations and genetic instability correlate with tumor progression and poorer prognosis. Low-grade papillary tumors usually arise from simple hyperplasia and/or minimal dysplasia and are characterized by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 9 and activating mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha isoform (PIK3CA) and inactivating mutations of STAG2. Low-grade papillary non-muscle-invasive BC can progress to muscle-invasive BC as a result of gaining CDKN2A loss. Muscle-invasive BC arises from flat dysplasia or carcinoma in situ (CIS); the lesions show TP53 mutations and LOH of chromosome 9. The invasive carcinoma can then further gain RB1 and PTEN loss along with other alterations acquiring metastatic potential. Overall, non-muscle-invasive BC usually show diploid or near-diploid karyotypes and fewer copy number alterations compared to muscle-invasive BC. Muscle-invasive BC is usually aneuploid, with numerous chromosomal alterations.[1][11]

Histopathology

The urinary bladder wall is composed of 4 layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. The mucosa has a normal urothelium comprised of a five to seven cell thick layer of stratified non-squamous epithelium (transitional cell epithelium) of uniform cells with large umbrella cells on top. BC originates from the urothelium; the majority of BC are urothelial; other uncommon types include squamous cell carcinoma, small-cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma.

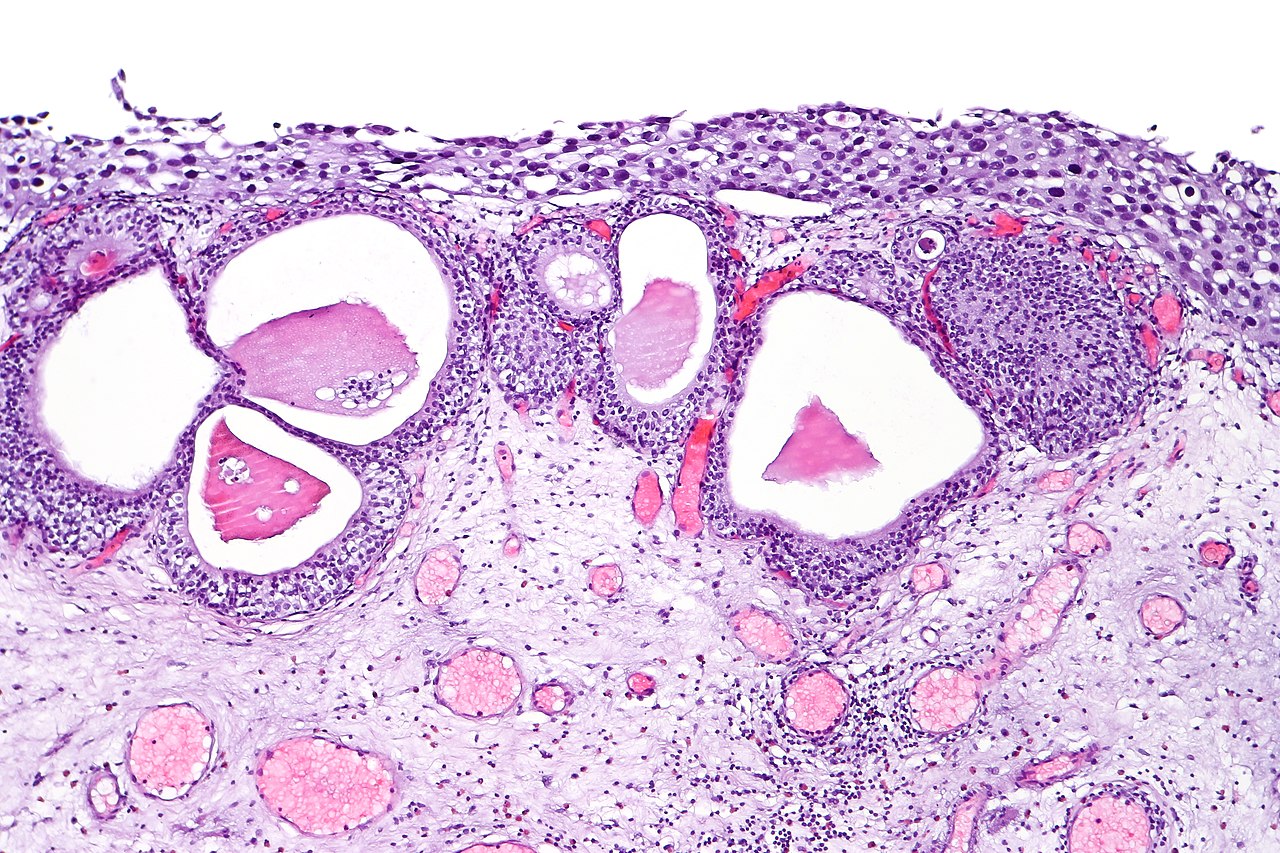

UC of the urinary bladder is subdivided based on the morphology and pathway into papillary (papilloma, low malignant potential, and papillary carcinoma) and flat (urothelial carcinoma in situ and invasive) categories (see Image. Urothelial Carcinoma in Situ in the Setting of Cystitis Cystica et Glandularis). The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies UC based on histopathology as low grade or high grade based upon the degree of nuclear anaplasia and architectural abnormalities. The histology of infiltrating UC is variable (see Image. Urothelial Carcinoma, Prostatic Infiltration). Most pT1 cancers are papillary, low, or high grade, whereas most pT2-T4 carcinomas are non-papillary and high grade. When UC present in association with non-urothelial forms, this association is known as UC with divergent differentiation. Possible morphologies include squamous, glandular, small cell, and even trophoblastic lines.[1][12]

Pathology plays a crucial role in the management of BC. At initial diagnosis, most patients present with non-muscle-invasive BC, which correlates with better overall survival and prognosis. The most critical factor in the pathologic assessment of UC is identifying the extent of invasion to set proper staging. BCs can be unifocal or multifocal. The majority of cases present as multifocal. Multifocal tumors may be multiple independent or arise from a common origin. The pathology report should include: tumor location, tumor grade, tumor depth, presence/absence of CIS, and whether the detrusor muscle is present in the examined specimen. The pathology report should also include the presence of LVI or unusual (variant) histology. In complex or difficult cases, the recommendation is for an additional review by an experienced genitourinary pathologist.[12]

History and Physical

BC is a tumor of old adults (> 60 years). Common presenting symptoms include:

- Microscopic hematuria

- Gross hematurias

- Infection or obstruction.

Other less common symptoms include painful micturition, frequency, constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, weight loss, and a pelvic mass.

There are no screening tests for the early detection of BC. Gross hematuria correlates with advanced disease stage.[12]

Evaluation

Diagnostic modalities used in diagnosing BC include Imaging (ultrasound, intravenous urography (IVU), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)), cystoscopy, and biopsy. Cystoscopy is considered the gold standard for the initial management of BC. All abnormal lesions, such as flat reddish lesions, papillary lesions, or solid lesions, requires biopsy and histological evaluation. The ideal urinary bladder biopsy should include muscularis propria to assess for invasion (T1: subepithelial connective tissue invasion; T2: muscularis propria invasion). Fortunately, most patients present with non-muscularis propria invasion, which shows a better prognosis than muscularis propria invasion. With rare exceptions, muscle-invasive (T2) urothelial cancer is high grade. Renal and bladder ultrasound may be useful during the initial workup of some suspected bladder cancer cases. Some cases will benefit from CT urography (or IVU). Cytology remains an important diagnostic tool and should be performed on fresh urine. Cytology is also valuable in the follow-up of patients.[8][12][13]

Treatment / Management

The treatment strategy of UC depends on whether there is muscle invasion. Management of patients with non-muscle invasive UC is with endoscopic resection and risk-based intravesical therapy, like bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is a vaccine originally for tuberculosis, but has been shown to decrease recurrence and decrease progression (up to 37% compared to no BCG therapy) of UC when compared to chemotherapy. Patients should then undergo active surveillance, urine cytology screening, and/or adjunctive molecular screening. Cystectomy should be an option for tumors refractory to conservative management. Management of muscle-invasive UC is with cystectomy with or without chemotherapy. Neo-adjuvant / adjuvant therapy can be incorporated based on disease staging and the presence or absence of metastasis.[8][12]

Management algorithms have been developed to standardize the management of UC. Adult patients with hematuria should first undergo cytology and/or cystoscopy. If urine cytology or bladder biopsy is positive, the patient should undergo transurethral resection of bladder tumors (TURBT) or imaging of the upper urinary tract. Non-muscle invasive UC should be managed based on the risk stratification, while the management of muscle-invasive UC should be based on the extent and stage of the disease.

Management of non-muscle invasive UC has its basis on the risk stratification done following TURBT and relies on tumor stage, number, size, pathological grade, associated CIS, lymphovascular invasion, or presence of aberrant histology. Based on the risk assessment, patients are categorized as low, intermediate, or high risk. Criteria for low-risk tumors include primary, solitary, Ta, LG/G1, < 3 cm, no CIS; Intermediate-risk tumors: all tumors not defined in the two adjacent categories (between the category of low and high risk), High-risk tumors: any of the following: T1 tumor, HG/G3 tumor, CIS, multiple and recurrent and large (>3 cm) Ta G1G2 tumors (all conditions must be present).[12]

Management of low-risk patients is through a single postoperative instillation of intravesical chemotherapy followed by surveillance > 5 years; adjuvant intravesical treatment is not indicated. Intermediate risk patients are managed by a single installation of intravesical chemotherapy, followed by induction and 1 year of maintenance intravesical therapy with BCG or chemotherapy (mitomycin or doxorubicin), followed by life-long surveillance. High-risk patients are re-staged through TURB in 4-6 weeks. Based on the results, the patient is either managed by intravesical BCG or radical cystectomy.[12]

Management of muscle-invasive BC has its basis in the stage and whether the patient is a surgical candidate and whether the patient willing to accept the consequences of radical cystectomy. Stage II and III can be managed either with combined cisplatin/radical cystectomy or combined modality (TURBT and chemoradiation). Stage IV metastatic disease treatment is with platinum-based chemotherapy combination. Two combinations have been found to be equally efficient; the first includes a combination of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) and is generally regarded as the standard first-line regimen. The second combines gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC). Checkpoint inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death-1 protein (PD-1) or its ligand (PD-L1) is the preferred option for refractory patients to platinum-based chemotherapy regimens.

Radical cystectomy entails the resection of the bladder, adjacent organs, and regional lymph nodes. In men, resection of the prostate and seminal vesicles are usually done. In women, resection of the uterus, cervix, ovaries, and anterior vagina is the norm. Urinary diversion through an orthotopic neobladder is the preferred urinary diversion procedure because it enables the patient to void and thereby improves the patient’s quality of life.[8]

Differential Diagnosis

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Hemorrhagic cystitis

- Prostatitis

- Urinary tract infection

- Nephrolithiasis

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Renal urothelial carcinoma

- Gynecologic cancer or other pelvic cancers

- Radiation cystitis

- Diverticulitis

Staging

TNM system

T category

- Ta lesions – Ta tumors are papillary (exophytic) lesions that tend to recur.

- Tis: – high-grade intraepithelial neoplasm without invasion into subepithelial connective tissue.

- T1 lesions – T1 tumors invade the submucosa or lamina propria.

- T2 lesions – Invasion into muscle is present in T2 lesions.

- T3 lesions – T3 tumors extend beyond muscle into the perivesical fat.

- T4 lesions – Tumor invading the prostate, vagina, uterus, or bowel is classified as T4a, while a tumor fixed to the abdominal wall, pelvic wall, or other organs is T4b.

Lymph node N

- NX Lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0 No lymph node metastasis

- N1 Single regional lymph node metastasis within the true pelvis (perivesical, obturator, internal and external iliac, or sacral lymph node)

- N2 Multiple regional lymph node metastases within the true pelvis

- N3 Lymph node metastasis spread to the common iliac lymph nodes

Distant metastasis (M)

- M0 No distant metastasis

- M1 Distant metastasis

- M1a Distant metastasis limited to lymph nodes beyond the common iliac arteries

- M1b Non-lymph-node distant metastases

Clinical Staging

- Stage I: T1, N0, M0

- Stage II: T2, N0, M0

- Stage III:

- Stage IIIA: T3a, T3b, or T4a; N0; M0 or T1 to T4a, N1, M0

- Stage IIIB: T1 to T4a, N2 or N3, M0

- Stage IV:

- Stage IVA: T4b, any N, M0 or any T, any N, M1a

- Stage IVB: any T, any N, M1b

Prognosis

The prognosis of UC depends on multiple factors. TNM stage is the most important prognostic factor of urinary bladder carcinoma. The 5-year overall survival (OS) for pT1 is 75%, for pT2 is 50%, and for pT3 is 20%. The invasion of muscularis propria determines whether the patient staging is pT1 vs. pT2. Some histologic variants of UC have a relatively poorer prognosis when compared to typical UC. These variants include urothelial carcinoma with rhabdoid features, urothelial micro-papillary carcinoma, plasmacytoid carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma. Other poor prognostic factors of UC include lymphovascular invasion, the presence of urothelial carcinoma in situ, recurrence, large tumor size, and multicentricity.[12]

Complications

Complications of UC include symptoms related to the tumor and treatment of adverse effects. Complications related to the tumor include weight loss, fatigue, UTI, metastasis, and urinary obstruction leading to chronic kidney failure.[14]The adverse effects of surgical management include UTI, urinary leak, pouch stones, urinary tract obstruction, erectile dysfunction, and vaginal narrowing.

Consultations

- Urology

- Oncology

- Nephrology

- Palliative care clinicians

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should know that painless gross hematuria, UTI, or irritative bladder symptoms may be early symptoms of UC.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

BC is a prevalent disease with substantial morbidity and mortality that requires interprofessional medical and surgical management. All patients with persistent hematuria should be referred to a urologist for workup.