Continuing Education Activity

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a common fungal infection in uncontrolled asthmatics, cystic fibrosis patients, and immunocompromised patients. Early diagnosis and rapid implementation of proper management are critical to prevent complications and/or disease progression. Diagnosis centers around classic clinical manifestations, radiographic findings, and immunological findings. This activity describes the etiology, evaluation, and management of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

- Describe the clinical and imaging modalities used to diagnose allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

- Explain how to educate high-risk patients on the prevention of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

- Explain the importance of improving coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Introduction

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a fungal infection of the lung due to a hypersensitivity reaction to antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus after colonization into the airways. Predominantly it affects patients with bronchial asthma and those having cystic fibrosis. It characteristically presents with bronchospasm, pulmonary infiltrates, eosinophilia, and immunologic evidence of allergy to the antigens of Aspergillus species.[1][2]

Etiology

Aspergillus species are molds that are present ubiquitously in the environment, especially in the organic matter. There are over 100 species worldwide, but most of the illness is caused by Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, and Aspergillus clavatus. An infection by Aspergillus species causes a broad spectrum of illnesses in humans and depends on the immune status of the host, ranging from hypersensitivity reactions to direct angioinvasion.

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common ubiquitous airborne fungus causative organism for ABPA.[3]Aspergillus conidia, because of its small diameter (2 to 3 micrometers), easily reach the pulmonary alveoli and deposits there.

ABPA affects people who are asthmatic or have cystic fibrosis and are allergic to Aspergillus. The thick mucus in the airways of these patients makes it difficult to clear up the Aspergillus spores when inhaled. Genetic association: HLA-DR molecules DR2, DR5, and possibly DR4 or DR7 contribute to susceptibility; whereas, HLA-DQ2 contributes to resistance, and a combination of these may determine the outcome of ABPA in CF and asthma.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis commonly presents in the third to fifth decade of life. It is also common in children. It usually found in severe asthmatics and patients with cystic fibrosis.[3][6]

Allergy to Aspergillus, as shown by a positive skin prick test to Aspergillus antigen, is present in almost 25% asthmatics and 50% of cystic fibrosis patients, but ABPA is not that much prevalent. The prevalence of ABPA in asthma and cystic fibrosis is about 13% and 9%, respectively.[7] Worldwide, more than 4 million people are affected by ABPA.[8]

A. fumigatus is the most common organism that causes ABPA, and the fungus requires dead organic matter to survive. The highest incidence of the infection is known to be in the winter season around the world (secondary to fallen leaves).

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis remains incompletely understood.[9] A. fumigatus spores that get inhaled in sufficient quantities behave as allergens. Normally a low level of IgG against fungal antigens in the circulation and the low antifungal secretory IgA in bronchoalveolar fluid suggest that healthy individuals can effectively eliminate fungal spores.[10][11] In contrast, exposure of atopic individuals to fungal spores or mycelial fragments results in the formation of IgE and IgG antibodies.

Th2 cells (Helper T cells) play an essential role in the hypersensitivity reaction caused by the A. fumigatus antigen. It manifests as IgE production, eosinophilia, mast cell degranulation, and bronchiectasis.[8]

A. fumigatus proteases release proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8, which causes epithelial cell damage and disruption of protective barriers, which triggers the hypersensitivity reaction. It also releases cytokines interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which increases blood and airway eosinophils as well as IgE.

- Immunocompetent individuals easily eliminate Aspergillus conidia from the airway by the innate immune system mechanisms; therefore, there are no manifestations of pulmonary fungal infections. If isolated in respiratory secretions like sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage, then it only reflects colonization, not an infection.

- Immunocompromised individuals do not eliminate Aspergillus conidia due to host immune defense imbalance; therefore, they colonize airways and germinate into somatic hyphae that stimulate a chronic allergic inflammatory response that results in tissue injury, which ultimately leads to the clinical features of ABPA.[7]

- In atopic individuals (asthmatics), cystic fibrosis patients, and in patients with cavitary lung diseases, inhalation of Aspergillus fumigatus spores triggers an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity response in the respiratory tract that causes respiratory symptoms like cough with expectoration and breathlessness.

Histopathology

Histopathologically, there is chronic bronchial inflammation, eosinophilia (leading to the development of an area of parenchymal scarring), airway remodeling, and bronchiectasis. Bronchi may show impacted mucus plug containing fungal hyphae, fibrin, Charcot-Leyden crystals, Curschmann spirals. The dichotomous branching of hyphae occurs at 45-degree angles.[8]

History and Physical

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis occurs primarily in patients with asthma or cystic fibrosis.

Clinical presentation[7]:

- History of recurrent episodes of wheezing with radiological evidence of patchy fleeting pulmonary infiltrates and bronchiectasis. Wheezing is not always evident, and some patients present with asymptomatic pulmonary consolidation.

- History of uncontrolled asthma with increased frequency and severity despite optimum asthma medications.

- History of cystic fibrosis.

- A presentation of cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, blood-stained sputum, or sputum with brown mucus plugs.

- There are non-specific complaints like anorexia, fatigue, generalized aches and pains, low-grade fever, and loss of weight.

- ABPA may occur with allergic fungal sinusitis having symptoms of chronic sinusitis with purulent sinus discharge.

On physical examination:

- In asthmatic patients with ABPA, wheezing, and/or rhonchi present on auscultation.

- In cystic fibrosis patients with ABPA, crepitations present on auscultation due to bronchiectasis.

- Tachypnea may present in case of asthma exacerbation or due to a secondary lung infection.

Evaluation

There is no individual test that establishes the diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. The diagnosis is based on classic clinical manifestations, radiographic findings, and immunological findings.[7]

Aspergillus skin test:

- Aspergillus skin test (AST) is the investigation most commonly used for diagnosing sensitization to A. fumigatus.

- It reveals immediate cutaneous hypersensitivity to A. fumigatus.

- A positive Type I Hypersensitivity reaction is typical of ABPA and represents the presence of A. fumigatus-specific IgE antibodies.

- Intradermal skin tests are more sensitive than the skin prick test for the diagnosis of Aspergillus sensitization.

Blood Abnormalities:

- Elevated total serum IgE (usually over 1000 IU/mL)

- Elevated specific serum IgE to A. fumigatus (Af)

- Presence of serum precipitins (by gel diffusion) or raised specific serum IgG to A. fumigatus

- Peripheral blood eosinophilia (often absent, especially if the patient is on oral or inhaled corticosteroids)

Radiological manifestations of ABPA:

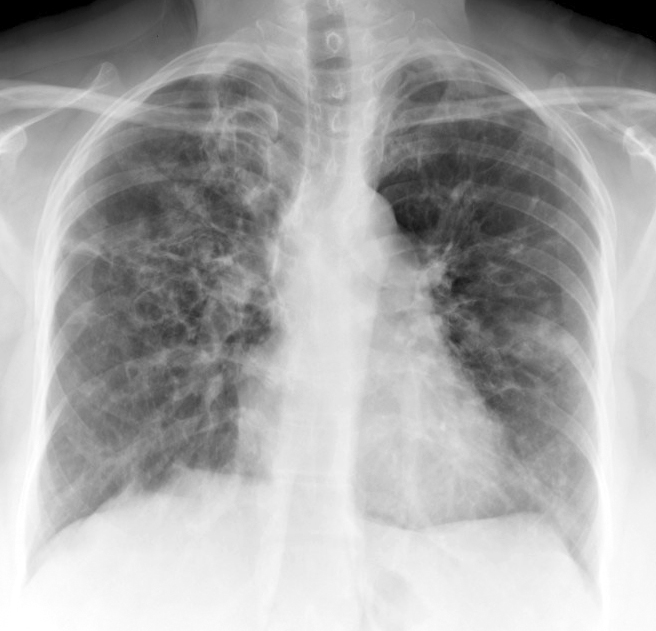

- Chest X-ray has 50% sensitivity for the diagnosis of ABPA. It can show parenchymal infiltrate and bronchiectasis changes mostly in the upper lobes; however, all lobes may exhibit involvement.

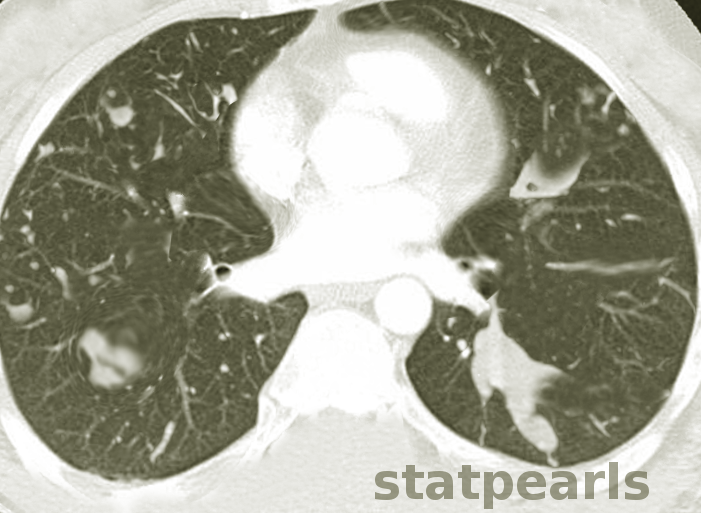

- HRCT Chest is the investigation of choice to detect bronchiectasis distribution and other abnormalities that are undetectable on a chest X-ray, such as centrilobular nodules and tree-in-bud appearance.

- Patients of ABPA with no abnormalities on HRCT chest are labeled as serologic ABPA (ABPA-S).

- Patients with central bronchiectasis on HRCT are labeled as ABPA Central Bronchiectasis (ABPA-CB).

The following shadows may present radiologically:

- “Finger in glove” opacity: suggestive of mucoid impaction in dilated bronchi.

- “Tramline shadows”: suggestive of parallel linear shadows extending from the hilum in bronchial distribution and reflecting longitudinal views of inflamed, edematous bronchi

- “Toothpaste shadows”: representing mucoid impaction of the bronchi

- “Ring shadows”: reflecting dilated bronchi with inflamed bronchial walls

Revised radiologic classification of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis based on findings on a high-resolution computed tomography of the chest.[12]

- ABPA-S (Serological ABPA): Fulfills the diagnostic criteria of ABPA with an absence of any radiological finding of ABPA on HRCT of the thorax.

- ABPA-B (Bronchiectasis ABPA): Satisfies the diagnostic requirements of ABPA along with the presence of bronchiectasis.

- ABPA-HAM (ABPA- High attenuation mucus): ABPA, along with the presence of high attenuation mucus on HRCT of the thorax.

- ABPA-CPF (ABPA-Chronic pleuropulmonary fibrosis): Fulfills the diagnostic criteria of ABPA with at least two radiological features suggestive of fibrosis (including fibrocavitary lesions, pulmonary fibrosis, pleural thickening) without the presence of mucoid impaction (or HAM).

Pulmonary function tests:

- Aids in measuring lung function impairment severity and monitoring improvement of lung function on follow up.

- Obstructive ventilatory defect: Stages I, III, IV, and often, V and may not correlate with the duration of ABPA or asthma.

- Patients with Stage V disease typically also have a restrictive ventilatory defect and a reduced DLCO.

Bronchoscopy: Mucoid impaction may be evident, and bronchial brushings may reveal mucus that contains aggregates of eosinophils, fungal hyphae, and eosinophil-derived Charcot–Leyden crystals. The finding of hyphae-filled mucus plugs is considered pathognomonic for ABPA. BAL fluid analysis from patients with ABPA: moderate eosinophilia (especially in steroid-naive patients) and increased levels of Aspergillus-specific IgE and IgA, but not IgG.

Sputum cultures for A. fumigatus: It is not diagnostic, but if it reveals an organism, then it helps in drug susceptibility test.

The following criteria are used for the diagnosis and typing of ABPA.

1) Rosenberg-Patterson criteria: It has eight major and three minor criteria.[13]

- Major criteria1. Asthma2. Presence of transient pulmonary infiltrates (fleeting shadows)3. Immediate cutaneous reactivity to Af (A. fumigatus)4. Elevated total serum IgE5. Precipitating antibodies against Af6. Peripheral blood eosinophilia7. Elevated serum IgE and IgG to Af8. Central/proximal bronchiectasis with normal tapering of distal bronchi

- Minor criteria1. Expectoration of golden brownish sputum plugs2. Positive sputum culture for Aspergillus species3. Late (Arthus-type) skin reactivity to Af

2) Criteria proposed by ISHAM working group :

- Predisposing conditions1. Bronchial asthma2. Cystic fibrosis

- Obligatory criteria (both should be present)1. Type I - positive Aspergillus skin test (immediate cutaneous hypersensitivity to Aspergillus antigen) or elevated IgE levels against Af2. Elevated total IgE levels (greater than 1000 IU/mL)

- Other criteria (at least two of three)1. Presence of precipitating or IgG antibodies against Af in serum2. Radiographic pulmonary opacities consistent with ABPA3. Total eosinophil count over 500 cells/microliter in steroid naïve patients(If the patient meets all the other criteria, an IgE value less than 1000 IU/mL may be acceptable)

Cystic Fibrosis Foundation has revised the criteria for the diagnosis of ABPA in patients with cystic fibrosis. ABPA is diagnosed and should be treated if the following are present:

1. Deterioration of cough, wheeze, sputum, or deterioration in pulmonary functions

2. Total serum IgE level more than 1000 IU/ml or greater than twofold from baseline

3. Aspergillus precipitins or increased Aspergillus specific IgG or IgE

4. New infiltrates on chest radiograph or CT scan

If patients have new radiographic findings, symptoms, or an increase in baseline IgE to more than 500 IU/ml, even then treatment of ABPA should be given to cystic fibrosis patients.

Treatment / Management

The main aim of the treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is to control episodes of acute inflammation and to limit progressive lung injury.

Goals of treatment:

• Controlling symptoms • Preventing exacerbations • Preserving normal lung function

Drugs used for the treatment of ABPA[7]:

- Anti-inflammatory drugs: corticosteroids

- Antifungal drugs

- Anti IgE therapy

- Antibiotics

Corticosteroids: Systemic corticosteroids are the primary therapy for ABPA. The steroids help to relieve the symptoms and decrease airflow obstruction, decrease serum IgE and reduce peripheral blood eosinophils. Moreover, there is a resolution of pulmonary inflammation, pulmonary infiltrates, and it prevents irreversible lung damage.

- Prednisolone is a commonly used drug for treatment.

- Dose: 0.5 to 1 mg/kg a day for two weeks, followed by 0.5 mg/kg every other day for 6 to 8 weeks. A subsequent taper (by 5 to 10 mg every two weeks) over the 3 to 5 months. The duration of treatment depends upon the activity and severity of the disease. A low maintenance dose (5.0 to 7.5 mg/d) may be required long term to control the disease and prevent recurrence in some patients.

- IgE levels should be monitored within a few months of an acute episode or exacerbation and require followup every two months. Escalation of steroid therapy should be an option if IgE levels rise more than 100%.

- Inhaled corticosteroids may help to control of bronchospasm and may minimize the dose of systemic steroids.

- Stage 1 & 3 requires oral/intravenous corticosteroids to control the acute stage and exacerbation.

- Stage 2 disease requires careful regular follow up.

- Stage 4 disease requires long-term steroids to control asthmatic symptoms and keep IgE levels at baseline.

- Stage 5 & 6 disease requires long-term corticosteroid use.

Oral antifungal agents: Antifungal agents act by decreasing the fungal load that reduces inflammatory activity and act as steroid-sparing agents. Antifungal therapy may help to decrease exacerbations.

- Itraconazole is a commonly used drug for treatment.

- Itraconazole (200 mg twice daily for 16 weeks) leads to significant reductions in corticosteroid dose, decreases IgE levels, resolves pulmonary infiltrates, improves exercise tolerance, and improves pulmonary function.

- Itraconazole treatment (200 mg/d or every other day) is generally recommended for patients with ABPA who are steroid-dependent, have frequent relapses, and where benefits of treatment outweigh the risks.

- Other antifungal agents, including nystatin, amphotericin B, miconazole, clotrimazole, and natamycin, are generally ineffective in controlling ABPA. Ketoconazole may be effective, but hepatotoxicity limits its utility.

- Newer antifungal drug: Voriconazole (300 to 600 mg/day) or posaconazole (800 mg/day) shows clinical improvement with a reduction in the requirement of oral glucocorticoids, improvement in asthma control, and decline in IgE levels. Cost is a major current limitation; however, the high rate of efficacy shows that treatment with these agents as second-line therapy is justified in specific patients.[14]

- Nebulized lipid amphotericin B (AMB-L) requires further studies to determine efficacy; therefore, at this time, it is not used for the treatment of ABPA.

Antibiotics: To prevent or treat an associated secondary bacterial infection.

Omalizumab: An anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody which prevents binding of IgE to Fc-epsilon RI receptor on mast cells and basophils.

- It is mainly used to treat uncontrolled asthma on Step 4 GINA treatment guideline.

- Very expensive drug.

- According to various studies and cases, it is a good alternate option in patients of ABPA with CF in whom steroid dependency and with contraindications to steroids. It also has a steroid-sparing effect and decreases systemic inflammatory markers.[15][16]

- Dosage: 375mg SC injection every two weeks for at least 4 to 6 months. The dosage depends upon the serum total IgE level. In ABPA, despite a high level of IgE, the routine dose of omalizumab is sufficient.[17]

Supportive measures:

- Airway clearance treatment to ABPA-related bronchiectasis patients should be prescribed nebulization with hypertonic saline with salbutamol and mucus clearance valves or percussion vests.

- Avoid areas and environmental conditions with high mold counts, such as decomposing organic materials and moldy indoor environments.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis[18]:

ABPA mimics many diseases that involve both airway and lung parenchyma. Undiagnosed lung infiltrates, pneumonia, bronchiectasis make a long list of differential diagnoses. Following are few diseases which should be carefully ruled out while making a diagnosis of ABPA:

- Corticosteroid-dependent asthma without ABPA

- Severe asthma with fungal sensitivity (SAFS)

- Cystic fibrosis (CF)

- Bronchiectasis

- Chronic necrotizing aspergillosis

- Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Churg–Strauss syndrome

- Bronchocentric granulomatosis

- Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (including drug-induced pneumonitis)

- Pulmonary tuberculosis

- Parasitic infections

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Itraconazole interferes with the hepatic metabolism of several medications, including cyclosporine, oral hypoglycemics, tacrolimus, terfenadine, cisapride, and midazolam. Deranged liver function test results, rash, headache, edema, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are the most common side effects. Impaired absorption is most significant with proton pump inhibitors.[19]

Glucocorticoids side effects: Weight gain, osteopenia, acne, skin atrophy, diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, cataracts, avascular necrosis of bone, infection, hypertension, and growth retardation in children.

Omalizumab side effects: The most common reaction is swelling and redness at the injection site. Anaphylaxis may occur in asthmatics.

Staging

New Proposed clinical staging of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in asthmatic patients[7]:

Stage 0: Asymptomatic

- No previous diagnosis of ABPA

- Controlled asthma (according to GINA/EPR-3 guidelines)

- Fulfilling the diagnostic criteria of ABPA (ISHAM working group criteria)

Stage 1: Acute

- No previous diagnosis of ABPA

- Uncontrolled asthma/symptoms consistent with ABPA

- Meeting the diagnostic criteria of ABPA

- 1a: With mucoid impaction - Mucoid impaction observed on chest imaging or bronchoscopy

- 1b: Without mucoid impaction - Absence of mucoid impaction on chest imaging or bronchoscopy

Stage 2: Response

- Clinical and/or radiological improvement and

- Decline in IgE by greater than or equal to 25% of baseline at 8 weeks

Stage 3: Exacerbation

- Clinical and/or radiological worsening and

- Increase in IgE by ≥ 50% from the baseline established during response/remission

Stage 4: Remission

Sustained clinical-radiological improvement and

- IgE levels persisting at or below baseline (or increase by less than 50%) for greater than or equal to 6 months off treatment

Stage 5a: Treatment-dependent ABPA

- Greater than or equal to two exacerbations within six months of stopping therapy or

- Worsening of clinical and/or radiological condition, along with immunological worsening (rise in IgE levels) on tapering oral steroids/azoles

Stage 5b: Glucocorticoid-dependent asthma

- Systemic glucocorticoids required for control of asthma while the ABPA activity is controlled (as indicated by IgE levels and thoracic imaging)

Stage 6: Advanced ABPA

- Extensive bronchiectasis due to ABPA on chest imaging and

- Complications (cor pulmonale and/or chronic type II respiratory failure)

EPR-3: third expert panel report; GINA: global initiative against asthma.

Prognosis

The natural history, progression, remission, and recurrences of ABPA are not well understood. Patients without central bronchiectasis at the time of diagnosis tend to maintain their lung function despite occasional exacerbations.[20] With appropriate treatment, long-term control of ABPA is feasible, and durable remissions are common.

Treatment of Stage 1 disease using corticosteroids typically results in decreased sputum production, improved control of bronchospasm, over 35% reduction in total IgE within 8 weeks, clearing of precipitating antibodies, and resolution of radiographic infiltrates. IgE levels typically do not completely normalize, but it decreases by approximately one-half of peak levels seen in the acute stage.

Progression of Stage 5 disease to pulmonary fibrosis may be preventable if patients maintain therapy on low-dose steroids. Persons with an FEV1 persistently under 0.8 L have a worse prognosis.

Complications

Complications of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis include[21][22][23]:

- Recurrent asthma exacerbations and steroid dependence

- Aspergilloma

- Invasive aspergillosis

- Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis

- Cavitation

- Local emphysema

- Chronic or recurrent lobar atelectasis

- Honeycomb fibrosis

- Complications related to bronchiectasis like hemoptysis, recurrent pulmonary infection

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis have to be more conscious about the worsening of their symptoms. If the worsening of respiratory symptoms occurs on treatment or new respiratory symptoms develops on stage 2 and stage 3, then immediately consult a pulmonologist.

Patients with ABPA-CB have a higher chance of getting a secondary infection and complications related to bronchiectasis. If fever or hemoptysis occurs, then immediately consult a pulmonologist.

If a patient is receiving long-term oral corticosteroids, all adverse drug effects should be properly understood. Screening should be performed for corticosteroid adverse effects of osteoporosis/osteopenia (by bone density measurement) and cataracts (by eye exams) regularly.[24]

Patients bronchiectasis should receive training on sputum clearance techniques. Recommendations are for influenza and pneumococcal immunizations.[24]

Avoid areas and environmental conditions with high mold counts, such as decomposing organic materials, and moldy indoor environments.

Pearls and Other Issues

- All patients with asthma and CF, regardless of the severity of the level of control, should routinely have screening for ABPA using A. fumigatus-specific IgE levels.

- Glucocorticoids should be the first-line of therapy in ABPA, and itraconazole reserved for those with exacerbations and glucocorticoid-dependent disease.

- Establishing IgE sensitization to Aspergillus through either skin prick test or measurement of specific serum IgE is a reasonable first step in an asthmatic being evaluated for ABPA. The inability to establish IgE sensitization to Aspergillus virtually excludes ABPA from consideration. If skin testing and/or specific IgE are positive, then a total serum IgE, precipitins to Aspergillus, and an eosinophil count should be assayed. Furthermore, chest imaging, preferably with a high-resolution chest CT, is necessary as well.

- Early detection and treatment can prevent the development of bronchiectasis or pulmonary fibrosis that otherwise occurs in the later stages of the disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is a fungal infection of the lung secondary to a hypersensitivity reaction to antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus. This disease process is uncommon; however, routine screening is necessary for asthmatic and cystic fibrosis patients. The interprofessional approach of pulmonologists, infectious diseases, primary care physicians, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals is essential to educate and improve patient outcomes. [Level V] A focused history and physical examination along with appropriate imaging with a high-resolution chest tomography of the chest are critical to establish an early diagnosis and initiate early treatment to prevent the development of bronchiectasis or pulmonary fibrosis. As targeted immunotherapy is evolving, there may be new treatment options in the near future.

The nurse place an important role in monitoring the patient for progression or worsening symptoms that must be reported back to the interprofessional team leader. As drug therapy and monitoring are complex in these patients, a pharmacist should evaluate for drug-drug interactions and coordinate drug therapy, assisting in monitoring for compliance and side effects and reporting to the clinical team leader if untoward complications arise. The nurse practitioner, a physician assistant, must coordinate care and patient and family education together so that they are aware of the need to monitor treatment, follow up regularly, and return for reassessment if unexpected complications occur. This disease is challenging to treat, and only through coordinated interprofessional care will the best outcomes be achieved. [Level V]