Continuing Education Activity

Unilateral vocal cord paralysis (UVCP) presents with dysphonia, shortness of breath and swallowing difficulty. It occurs secondary to damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which usually occurs as a result of cancers, trauma, or surgery. Making the definitive diagnosis of unilateral vocal cord paralysis requires taking an extensive clinical history, performing a thorough examination, and carrying out an investigation to identify the underlying cause. This should be done by Otolaryngology, as this team is usually best equipped to restore a patient's voice with a variety of surgical and non-surgical interventions when vocal restoration is possible. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of unilateral vocal cord paralysis and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance outcomes for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the common causes of unilateral vocal cord paralysis.

- Review the presentation of a patient with unilateral vocal cord paralysis.

- Outline the management options for unilateral vocal cord paralysis.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with unilateral vocal cord paralysis.

Introduction

Unilateral vocal cord paralysis (UVCP) is a common presentation to otolaryngology outpatient clinics. The condition presents with dysphonia, shortness of breath and swallowing difficulty, and occurs secondary to damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve by causes such as cancers, trauma, and surgery. UVCP requires extensive clinical history taking, examination, and investigation by an experienced otolaryngologist to identify the underlying cause. The otolaryngologist can often restore the patient's voice with a variety of surgical and non-surgical interventions.

Etiology

The etiology of UVCP varies with geography and time. Data obtained from 1985 through 1995 in one of the largest North American case series,[1] showed cancer to be the most common cause of UVCP. This shifted to iatrogenic surgical injury (37%) from 1996 through 2005, with non-thyroid procedures (66%) surpassing thyroidectomy (33%) as the most common mode of injury. By contrast, a large Italian study[2] showed thyroidectomy (41.3%), idiopathic paralysis (25.3%), and thoracic surgery (12.1%) to be the chief implicating factors.

Malignancy is the most worrisome cause of UVCP and is most commonly seen in primary and metastatic lung and laryngeal carcinoma, with thyroid and central nervous system (CNS) cancers less frequently seen.

Iatrogenic injury has traditionally been attributed to thyroidectomy operations, the likelihood of which increases when there is aberrant anatomy of the recurrent laryngeal nerve.[3] Intra-operative nerve stimulators are frequently used to avoid injury, but their effectiveness has not been clinically proven.[4][5] Other surgeries that lead to injury of the recurrent laryngeal nerve include anterior cervical spine surgery, oesophagectomy, and cardiothoracic surgery, although any procedure during which an endotracheal tube can put prolonged pressure on the nerve may result in paralysis.

Traumatic UVCP is common but not well understood, with proposed mechanisms of injury including direct recurrent laryngeal nerve trauma and arytenoid dislocation.[6]

There are a host of diseases that may present as a less common cause of UVCP. Therefore, careful history and examination instead of extensive serological testing, will help guide diagnosis. Such causes can include neurological (stroke, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis), inflammatory (sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus), and infectious (Varicella Zoster, Lyme disease) conditions.

Although common, idiopathic paralysis is poorly understood and is thought to be secondary to viral or inflammatory disease. Idiopathic disease should only be diagnosed when all other causes have been excluded.

Epidemiology

The etiology and diagnosis of UVCP are complex. There is no definitive epidemiological data published on its incidence within the general population. A comparison of patient demographics between neurological and non-neurological causes has noted no statistically significant difference in age, gender, or duration of symptoms, with only a past medical history of cancer or thyroid disease being significantly more common in the neurogenic group.[7]

Pathophysiology

The recurrent laryngeal nerve arises from the tenth cranial nerve (CN X) (Vagus) and has a long course throughout the neck and thorax. The nerve loops under the arch of the aorta on the left and the subclavian artery on the right before returning to the larynx. There can be significant variation in anatomy, with a small proportion of the population having a non-recurrent laryngeal nerve.[8] It provides sensation to the glottis and sub-glottis, and motor innervation to the intrinsic muscles of the larynx responsible for abduction and adduction of the vocal cords. Resultantly, any lesion, inflammation, or trauma throughout the length of the nerve can cause an absence of cord movement and dysphonia.

History and Physical

Patients with UVCP will present with a sudden onset of dysphonia, often described as a weak or "breathy" voice. In addition to voice change, a significant proportion of patients will present with swallowing difficulties such as dysphagia and regurgitation. Many will also describe poor exercise tolerance, with shortness of breath on minimal exertion despite normal lung function.

Given the plethora of underlying etiologies, other features of the clinical history may indicate the cause. It is important to ensure the patient has no major red flags for head and neck cancer such as odynophagia, cervical lymphadenopathy, night sweats, referred otalgia, weight loss, and hemoptysis. A patient's past medical history including lung or cardiovascular disease, smoking, and alcohol consumption status are all important indicators of potential malignant disease. Occupational hazards, risk behaviors such as intravenous drug use, and foreign travel may suggest rarer causes.

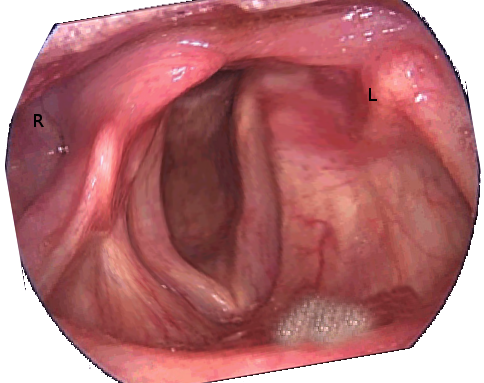

Clinical evaluation of the patient should include a full otolaryngological examination, with particular attention to inspection and palpation of the neck and flexible nasal endoscopy of the oropharynx and glottis. Assessment of voice quality can be graded with GRBAS scale (Grade, Roughness, Breathlessness, Aesthenia, Strain)[9] which has frequently shown the voice to be worse in a patient with UVCP.

Evaluation

Imaging

A chest x-ray can be used as a screening tool for suspected pulmonary causes, but is non-specific and will often miss more discrete lesion compared to cross-sectional imaging. CT scanning is the most favored investigation, and it is advised to image the patient from skull base to diaphragm to incorporate the entire length of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Although it is useful for the anatomical definition of malignant disease,[10] CT is limited by exposing the patient to ionizing radiation, expense and an overall low rate of diagnosis.[11] MRI can be used an alternative but has been criticized for a high rate of false-positive results.

Serological Tests

There is no strong evidence for use of routine serological testing, and these tests should only aid in the diagnosis of a particular etiology. Serum tests can be used in suspected inflammatory or infectious UVCP, with common tests including rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibodies, serum ACE, lyme titer, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Direct Visualization

Direct laryngoscopy of the glottis is the most sensitive and specific method of evaluating appearance and movement of vocal cords in a suspected iatrogenic injury.[12] It is easily performed in the outpatient setting and can be combined with video stroboscopy to give a detailed overview of cord movements.

Other Investigations

Laryngeal electromyography uses a percutaneous EMG needle to perform an electrophysiological evaluation of the intrinsic muscles of the larynx. Although growing in popularity, the test is not widely available, and a current consensus statement from the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine advises its use as a prognostic tool in patients who have been symptomatic between 4 weeks to 6 months.[13]

Neck and laryngeal ultrasound can be used to assess vocal cord movement[14] and investigate surrounding pathologies.[15] However, ultrasound does not yield the same anatomical definition as CT, requires an experienced ultrasonographer, and is less reliable in obese patients.

Treatment / Management

The aim of surgical management in UVCP is "medialization" of the affected cord to improve voice quality. There is no consensus on the timing of surgical intervention; however, surgeons traditionally propose a "watchful waiting" period of 6 to 9 months to accomodate for spontaneous motion recovery or accommodation by the unaffected vocal cord.

Injection thyroplasty involves injection of a substance close to the affected vocal fold, moving it medially to create better contact with the adjacent cord. The procedure can be performed under local or general anesthetic with equal efficacy.[16] Many materials have been used in injection thyroplasty, for example, autologous fat, cadaveric dermis, calcium hydroxy-apatite, methyl-cellulose, and hyaluronic acid; however, no high-quality evidence exists confirming the ideal material.[17] Teflon has previously been used, but this has fallen out of favor due to the formation of granulomas.[18]

Type 1 Isshiki thyroplasty is a more permanent, medialization technique wherein a window is cut into the thyroid cartilage, and the vocal cord moved medially through use of an implant. Like injection thyroplasty, there are numerous implant materials available.[19] Procedures including arytenoid adduction and arytenopexy can be performed concurrently, and voice outcomes are reported to be good at 1 and 3 years post-operatively.[20]

Laryngeal reinnervation utilizes functioning nerves in the vicinity of the recurrent laryngeal nerve to reestablish tone and movement within the larynx. The ansa cervicalis, phrenic, and hypoglossal nerves have all been used as nerve pedicles with good results on voice outcomes.

A systematic review by Siu et al. compared the outcomes of injection thyroplasty, type 1 thyroplasty, laryngeal reinnervation, and arytenoid adduction procedures. Despite a good body of evidence for all methods, no technique has shown a statistically significant advantage in voice outcome or quality of life compared to others.[21] Although healthcare professionals find type 1 Isshiki thyroplasty has a greater long-term benefit over injection techniques, there is a growing body of evidence that long-acting injectable materials have comparable longitudinal outcomes.[22] As a result, surgical intervention should be considered after a trial of conservative management, with the technique used based on surgeon experience and patient preference.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of UVCP can be divided into malignant or non-malignant.

- Malignant: Predominantly lung and laryngeal carcinomas

- Non-malignant: Typically traumatic or iatrogenic, with rarer causes including neurological, inflammatory and infectious

- Idiopathic: A diagnosis of exclusion only

Prognosis

Prognosis of UVCP varies wildly and depends on the underlying etiology. It has been proposed that around one-third of patients will experience motion recovery, although many of these patients will continue to have voice difficulties.[23] Laryngeal electromyography can give useful information on prognosis in patients with persistent dysphonia.[24]

Complications

The adverse effect on voice and swallowing can have a significant, detrimental impact on the patient's quality of life.[25] In particular, patients who rely on their voice for a living (teachers, singers, secretaries) may suffer significant psychological and financial difficulty as a result of UVCP. Incomplete closure of the glottis can also lead to a risk of aspiration, and despite being rare, this can lead to life-threatening aspiration pneumonia.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Voice rehabilitation with speech and language therapists (SLT) is an integral part of the management of UVCP and can be used both before and after surgical intervention. Management aims to improve glottic closure by increasing intra-abdominal pressure through humming and abdominal breathing. Studies have suggested that early voice therapy may help avoid the need for surgical intervention.[26] SLT teams are also invaluable in assessing voice quality following intervention; however, despite numerous measurement scales being available, there is no agreement on the most effective method of voice evaluation.[27]

Consultations

- Otolaryngological (ENT) surgeon

- Speech and language therapist

- Radiologist

- Involvement of the relevant specialist, for example, respiratory professional, an infectious disease specialist, oncologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

The initial presentation of dysphonia can be an unsettling symptom for patients, with many worried about a potential malignancy. Patients should be reassured that while malignancy is a common cause, there are numerous other, potentially reversible, causes of UVCP. Explanation of the long-term effectiveness of surgical and non-surgical management may dispel patient anxiety, as can the option of trying different treatments to see which modality works best for them. Speech and language therapists can be invaluable in providing reassurance and support through long-term management with voice therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The interprofessional team is essential to the diagnosis and management of UVCP. Through the use of clinical examination and direct laryngoscopy, otolaryngologists can help identify UVCP and formulate a differential diagnosis. Radiologists can further aid diagnosis through the use of cross-sectional imaging. Definitive management can be achieved with voice therapy and support from the speech and language therapists, with otolaryngologists providing surgical management in those who do not respond to initial therapy.