Continuing Education Activity

Richter hernia is a herniation of the anti-mesenteric portion of the intestine through a fascial defect. Patients often present with symptoms similar to other incarcerated hernias, such as abdominal discomfort, distention, nausea, and vomiting. The incidence of Richter's hernia has been increasing with the growing popularity of minimally invasive surgery. Operative treatment of these hernias depends on the viability of the involved portion of the bowel and may often require resection in addition to repair of the fascial defect. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of Richter hernias and highlights the interprofessional team's role in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of a Richter hernia.

- Review the workup of a patient with a Richter hernia.

- Summarize the treatment options for a Richter hernia.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to repair the fascial defect and resent the non-viable bowel, which will improve outcomes for patients with Richter hernias.

Introduction

Richter hernia is a less known entity of the hernia family. Although not well known and overall rare, Richter hernias can lead to grave clinical sequelae. A Richter hernia is a herniation of the anti-mesenteric portion of the bowel through a fascial defect. This exact phenomenon explains the often subclinical symptoms and late presentation. With the advent of minimally invasive surgery, there was an increase in the incidence of Richter hernias, which has only continued as minimally invasive surgeries have become more popular. Operative treatment of Richter hernias depends on the viability of the involved bowel and may often require bowel resection in addition to repair of the fascial defect.

Etiology

The Richter hernia gets its name from August Gottlich Richter, who described this hernia in 1785. Before this date, there were reported cases of a fascial defect that involved the anti-mesenteric portion of the bowel wall. Fabricius Hildanus first reported a case like this in 1598, which was followed by a few reports by Alexis Littre in 1700. Richter was the first to describe this hernia as a “partial enterocele.”[1] As time passed, others such as Antonio Scarpa further defined the pathophysiology. By 1887, Frederick Treves reported a case series of such hernias.

Epidemiology

Richter hernias typically occur in elderly patients between 60 to 80 years old; however, they can theoretically manifest at any age, and pediatric case reports exist. There is a slightly increased incidence in the female population. This predilection may reflect that femoral hernias occur more commonly in females than males, and the femoral ring is the most common site for a Richter hernia. Estimates are that approximately 10% of all hernias are Richter type hernias though this may be under-appreciated.[2]

The most common location for this pathology to occur is in the femoral canal (36 to 88%), followed by the inguinal canal (12 to 36%) and abdominal wall incisional hernias (4 to 25%).[3][2] As stated above, the increase in laparoscopic and robotic-assisted procedures has led to a rise in Richter type hernias because of unclosed port sites allowing for herniation of a portion of the bowel wall through the small fascial defect.

Pathophysiology

By definition, a Richter hernia is a herniation of only a portion of the circumference of the bowel wall through the fascial defect. Most commonly, it is the anti-mesenteric portion of the bowel. These hernias often develop in small fascial defects. The defect must be large enough for a portion of the bowel to protrude through but not large enough to accommodate the entire circumference of the bowel. In many cases, the segment of bowel involved is a segment of the terminal ileum.

The ensuing process results from the incarceration of a portion of the bowel wall. Incarceration of the intestine can lead to strangulation of the blood supply to that portion of the bowel followed by edema and venous congestion, leading to rapid segmental ischemia and gangrene with a reported incidence of necrosis of 69% at the time of operative intervention.[2][4]

History and Physical

Similar to the presentation of other incarcerated hernias, patients often present with abdominal discomfort, distention, nausea, and vomiting. The key difference is the delay in presentation. Because this hernia only involves a portion of the bowel wall, there is not a complete obstruction of the intestinal lumen. Obstructive symptoms rarely present if less than two-thirds of the bowel wall is involved. Lack of complete obstruction often leads to subclinical symptoms for a period until the process becomes advanced, and there is strangulation of the involved bowel resulting in an intensification of the above symptoms.

Upon presentation, it is essential to obtain a complete history and physical with particular attention to predisposing factors such as previous hernias and history of minimally invasive surgery. A careful inventory of the patient's medical history should be obtained with detail to comorbid conditions, active cardiopulmonary disease, and use of anticoagulation. When surgical intervention is required, patients may require additional treatment such as the reversal of anticoagulation or cardiac risk stratification based upon comorbid conditions.

Evaluation

There are many modes by which to evaluate a Richter hernia.

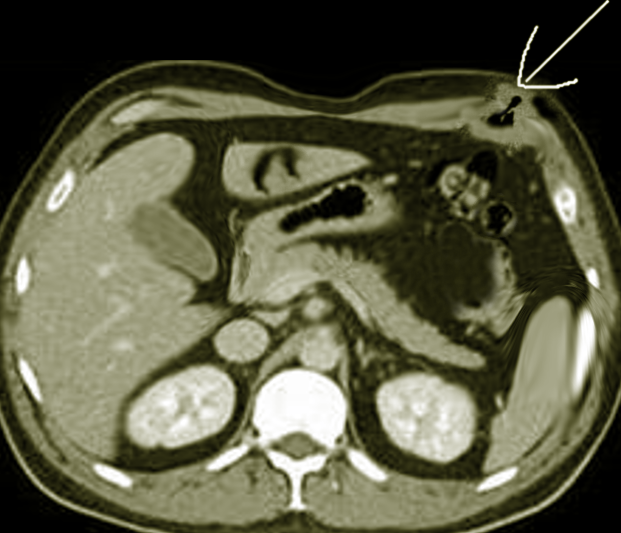

Outside of physical examination is the use of various imaging modalities. Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scans are useful adjuncts in diagnosis. However, as a Richter type hernia only involves a portion of the bowel wall, these imaging modalities can result in a false-negative result.

The inclusion of laboratory data is requisite, with the evaluation including complete blood count (CBC) and basic metabolic panel (BMP) to evaluate for leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, or electrolyte derangements. A PT/INR and/or PTT should be obtained to assess for any coagulopathy that needs to be corrected preoperatively in patients with hepatic dysfunction or patients on anticoagulation.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of Richter hernias depends on clinical status, physical examination, and suspicion of strangulation. Clinically stable patients with reducible hernias should undergo repair in the elective setting. Strangulated hernias of any type are a surgical emergency, and Richter type hernias do not deviate from this principle. Immediate operative exploration is required. Simultaneously resuscitation and treatment of sepsis should also be undertaken with intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

The surgical approach depends on multiple factors, including the location of the hernia, the clinical status of the patient, and surgeon preference. An open surgical procedure may be the best option for patients with evidence of hemodynamic instability, obstruction, or strangulation. The placement of the incision depends on the location of the hernia. Midline laparotomy is typically appropriate for ventral incisional hernias. Femoral and inguinal Richter type hernias may require inguinal incision with a counter laparotomy incision.

Minimally invasive hernia repair with either laparoscopic or robotic techniques should also is a consideration. Because of the need to establish pneumoperitoneum, these approaches are more conducive for hemodynamically stable patients without obstruction or strangulation. Dilated loops of the bowel may prevent safe laparoscopic access and provided limited room for establishing pneumoperitoneum. Hemodynamic instability is further exacerbated by pneumoperitoneum because of decreased venous return. Thus, a minimally invasive approach is often best suited for the urgent or elective setting. Transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and total extraperitoneal (TEP) approaches may be considered for inguinal or femoral defects. Various methods of minimally invasive ventral hernia repair are possible, including preperitoneal or intraperitoneal approaches.

Regardless of the surgical approach, surgeons must be careful to assess for bowel viability. Any questionable bowel should undergo resection and anastomosis undertaken. One group proposed that if the portion of ischemia is a small, coin-like lesion involving less than half of the bowel wall circumference, this may be invaginated, and the new edges reapproximated.[4] The bowel may be assessed for color and peristalsis though this does not correlate with viability, and thus the recommendation is for evaluation by standard methods.[5] Methods to evaluate bowel viability include intravenous injection of fluorescein and use of a Wood's lamp. A more modern approach to the Wood's lamp is the intravenous injection of indocyanine green and an infrared angiography evaluation.[6] One may also assess for arterial flow using a Doppler.

Repair of the hernia defect depends on the defect. The current standard of care for repairing most hernias, including femoral, inguinal, and incisional hernias, involves the placement of a prosthetic mesh. However, as there is often strangulated bowel requiring bowel resection in Richter type hernias, mesh placement is controversial. Ultimately, the decision of whether to place mesh and type of mesh depends on the surgeon’s clinical judgment.

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating Richter type hernias, the clinician must keep a broad differential diagnosis in mind. As previously discussed, these patients often present with abdominal pain. They rarely have symptoms of complete obstruction and may have vague symptoms. Differential diagnosis should include abdominal wall masses such as lipomas and abscesses. Consideration should be given to ileus and bowel obstruction along with their potential underlying causes (i.e., adhesions, hernias, intraluminal masses). It is often unknown until surgical intervention whether patients have a Richter type hernia. Thus differential diagnosis should include a strangulated hernia involving the complete bowel lumen, especially if presenting with sepsis and acute obstruction.

Prognosis

After successful hernia repair, there is always the potential for recurrence. Modifiable patient risk factors for recurrence include elevated BMI, smoking, diabetes, and steroid use. Risk factors related to surgery and technique include surgical site infection, development of seroma, tissue overlap, and surgeon experience.[7] As Richter hernias are often incisional hernias from prior procedures, there is a particular risk of recurrence with the repair of these defects estimated at 11%, with obesity as the most significant risk factor.[8]

Complications

Because of the initial lack of obstructive symptoms, Richter hernias may undergo chronic incarceration and, if left unaddressed, may present as an enterocutaneous fistula. Various published case reports with rare presentations of Richter type hernias have included colocutaneous fistula after inguinal hernia repair and laparoscopic gastric bypass.[9][10] These complicated presentations often require more extensive repair and recovery due to laparotomy and takedown of the fistula. Jayamanne et al. reported a case of Richter hernia through a perineal incision after proctectomy, which led to multiple trips to the operating room and difficulty with wound closure.[11]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Recovery after Richter hernia repair is centered around modifying risk factors for recurrence. Patients should be advised to refrain from smoking and heavy lifting. Continued attention to weight is a strong recommendation, as obesity is a risk factor for the development of hernias. An abdominal binder can be used in the postoperative period for comfort but is not necessary.

Deterrence and Patient Education

- The surgeon should educate patients pre-operatively about expectations regarding surgery, post-operative pain, and the recovery process.

- Surgeons should educate patients about the surgical procedure including risks such as bleeding, infection, damage to surrounding structures, need for further surgery, and recurrence.

- Patients should receive counsel that a bowel resection may be necessary, depending on the contents of the hernia.

- As part of this discussion, a review of the risks associated with resection and anastomosis such as anastomotic leak is in order.

- If high-risk comorbid conditions are present such as immunosuppressive therapy (i.e., chemotherapy, steroids, etc.) or inflammatory bowel disease, then the surgeon may discuss the risk of possible ostomy prior to surgery.

- Postoperative pain expectations should be reviewed which are particular to each surgeon. Surgeons should review activity restrictions following surgery. As discussed above, activity restrictions should include no heavy lifting for four to six weeks after surgery. The surgeons should counsel patients to refrain from activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure and smoking cessation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Richter hernias are difficult to diagnose as herniation of the anti-mesenteric portion of the bowel wall rarely results in complete luminal obstruction. As discussed, because of this, patients with an incarcerated Richter hernia may have a prolonged subclinical course and may present only when the process is advanced, and there is a high risk for bowel ischemia. Due to this, there is a crucial need for interprofessional discussion. When patients with abdominal pain present to the emergency department, and there is suspicion for an incarcerated hernia, which may even be strangulated, it is essential for emergency medical staff to involve the surgical team as early as possible. If there is a concern for strangulation, the consulting surgeon may proceed to the operating room based on physical examination rather than pursuing imaging studies. The mortality rate surrounding strangulated Richter hernias is 17%; thus, one must have a high index of suspicion and keep Richter type hernias in the differential when considering patients with abdominal pain.[2] [Level 5]