[4]

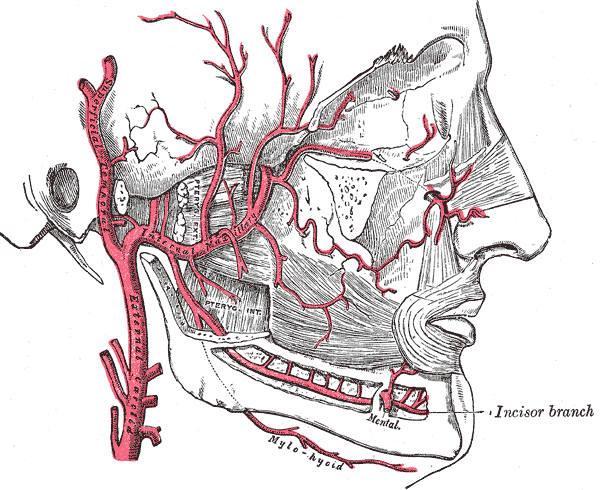

Alvernia JE, Hidalgo J, Sindou MP, Washington C, Luzardo G, Perkins E, Nader R, Mertens P. The maxillary artery and its variants: an anatomical study with neurosurgical applications. Acta neurochirurgica. 2017 Apr:159(4):655-664. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3092-5. Epub 2017 Feb 13

[PubMed PMID: 28191601]

[7]

Iimura J, Hatano A, Ando Y, Arai C, Arai S, Shigeta Y, Kojima H, Otori N, Wada K. Study of hemostasis procedures for posterior epistaxis. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2016 Jun:43(3):298-303. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.09.015. Epub 2015 Oct 31

[PubMed PMID: 26527519]

[8]

Wang L, Cai L, Lu S, Qian H, Lawton MT, Shi X. The History and Evolution of Internal Maxillary Artery Bypass. World neurosurgery. 2018 May:113():320-332. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.02.158. Epub 2018 Mar 7

[PubMed PMID: 29524709]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[9]

Akiyama O, Güngör A, Middlebrooks EH, Kondo A, Arai H. Microsurgical anatomy of the maxillary artery for extracranial-intracranial bypass in the pterygopalatine segment of the maxillary artery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Jul:31(5):724-733. doi: 10.1002/ca.22926. Epub 2017 Nov 29

[PubMed PMID: 28556192]

[10]

Yağmurlu K, Kalani MYS, Martirosyan NL, Safavi-Abbasi S, Belykh E, Laarakker AS, Nakaji P, Zabramski JM, Preul MC, Spetzler RF. Maxillary Artery to Middle Cerebral Artery Bypass: A Novel Technique for Exposure of the Maxillary Artery. World neurosurgery. 2017 Apr:100():540-550. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.130. Epub 2017 Jan 9

[PubMed PMID: 28089839]