Introduction

Upper eyelid reconstruction is a surgical procedure used to correct lid defects of the upper eyelid that occur from surgical resection of tumors, trauma, or congenital anomalies like a coloboma.[1] Reconstruction of upper eyelids due to surgical resections of neoplasms, such as skin cancers excised by Mohs micrographic surgery, requires additional consideration.[2] Restoration of the upper eyelid is much more complicated than the lower eyelid. Careful deliberation is necessary for the approach to reconstruction since the repair is highly dependent on the location and the extent of the defect.

The eyelids serve essential functions to the face. In addition to providing cosmetic appearance, the eyelid mechanically protects the cornea and the globe. Furthermore, meibomian glands in the tarsus produce lipids that, upon contraction of the tarsal orbicularis oculi, stabilize the tear film to prevent dry eye. To serve this function, the upper eyelid must descend to cover the cornea during blinking but must be mobile enough to clear the visual axis upon elevation.[3] Ptosis can significantly impact the visual fields and the cosmetic appearance of the face. An ideal upper eyelid reconstruction should, therefore, address any of these potential functional or aesthetic deficits that can occur from eyelid defects.

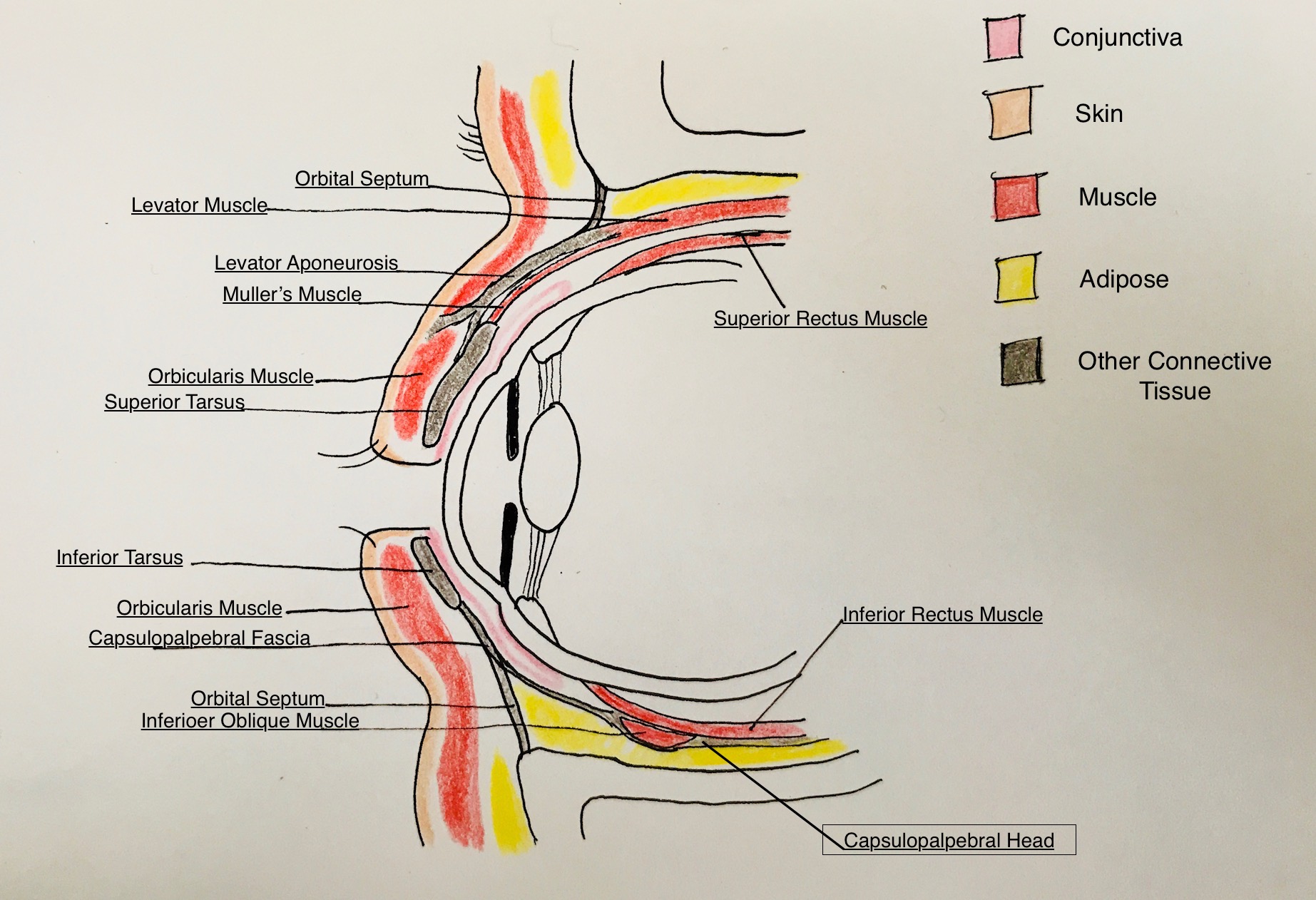

Anatomy and Physiology

The anatomy of the upper eyelid is multifaceted and is very important to the surgical approach. Several critical anatomic principles determine eyelid reconstruction. Firstly, the determination of which lamella of the eyelid is involved in the defect is a crucial part of the evaluation. The tarsal part of the upper eyelid splits into the anterior and posterior lamellae.[1] The septal eyelid also has a middle lamella made of the orbital septum, fat, and the upper eyelid retractors. The anterior lamella includes the skin and orbicularis muscle, while the posterior lamella consists of the tarsus and the palpebral conjunctiva. The skin is a stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium and is the thinnest in the body; this is because there are very few adnexal structures, such as hair or sebaceous glands. This factor is important for considering skin grafts to use. The orbicularis oculi receive innervation from the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve and are responsible for the closure of the eyelid. It divides into three components, which include the orbital, pre-septal, and pre-tarsal elements. Since the anterior and posterior lamellae contain different tissues, the surgeon should consider a different graft or flap for each portion

The amount of residual tarsus is also vital to evaluate since it provides the primary structural support to the eyelid and contains dense fibrous connective tissue. Knowledge about the dimensions is essential for an exact repair. The tarsus is approximately 28 to 29 mm in horizontal length and 1mm thick on average.[4] It reaches a maximum vertical height of around 10 mm in the center and tapers off at the edges.[4] It also provides a platform for re-epithelialization and contains meibomian glands that secrete lipids into the tear film and hair follicles of the eyelashes. The levator aponeurosis that branches off the levator palpebrae superioris suspends the tarsus. The bulbar conjunctiva is made of stratified non-keratinized squamous epithelium. The conjunctiva provides additional lubrication for the cornea and the globe. Any tissue that replaces the posterior lamella must have a stable lid margin, closely approximate the cornea and globe, but does not abrade the cornea by hair follicles or epithelium.

The neurovascular supply to the upper eyelid is also an essential anatomic consideration. The arterial supply of the upper eyelid primarily comes from the superior marginal and peripheral arcades that branch off the medial and lateral palpebral arteries.[2] The superior marginal arcade traverses between the pre-tarsal orbicularis and tarsus, around 2 to 3 mm above the lid margin. The peripheral arcade is above the tarsus between the levator aponeurosis and Muller’s muscle.[5] Therefore, the best survival of graft tissue will be closer to where these arcades run. Venous drainage is split into pre and post-tarsal regions. In the pre-tarsal upper eyelid, the angular vein drains the medial portion of the eyelid, and the superficial temporal vein drains the temporal region.[5] In the post tarsal area, venous drainage is provided by the orbital vein, anterior facial vein, and pterygoid plexus. Lymphatic drainage for the upper eyelid goes to the submandibular and pre-auricular lymph nodes. The lateral two-thirds of the upper eyelid drain into the pre-auricular nodes, while the medial one-third drains into the submandibular lymph nodes. It is critical to know the lymphatic drainage of the upper eyelid and clear any involvement of the lymph nodes before any tumor gets resected.

Preparation

A thorough assessment is necessary for all patients considered for eyelid reconstruction. A full history and physical exam should be done, including an evaluation for comorbidities that would affect wound healing, such as prior radiation to the face, smoking, or diabetes. It is necessary to determine that patients will be able to tolerate the surgery. If patients run the risk of being poor surgical candidates, then the risks and benefits of the surgery should be weighed with the patient. Any patient that developed a defect through trauma or congenital anomalies requires an evaluation to check for accompanying defects by the appropriate specialists.

The most crucial aspect of the preparation is the decision about the type of reconstructive technique to be used; finding the extent and location of the defect will be the determining factor in this decision. This evaluation includes whether it involves structures in the anterior or posterior lamellae, how much residual tarsus there is, whether it involves the lid margin, the residual vascular supply for any graft, whether it involves the medial or lateral canthus, and the tension that would form after repairing the defect. A single graft is not usable for anterior and posterior lamellar structures. Repairs involving the lid margin are more complicated than those that spare the lid margin. The tension on the repair determines the risk of wound dehiscence. Horizontal tension also determines the likelihood of lid retraction, which is more common with upper eyelid than lower eyelid reconstructions. Alterations to the reconstructive technique may be attempted while in the operating room. The types of reconstructive techniques used are listed below.

Technique or Treatment

The approach taken to reconstruction must be carefully assessed on an individual basis and discussed with the patient to evaluate their preferences. The following is a list of suggested methods for reconstruction based on the lamellar structures involved, and the length of the lid defect; this is by no means a fixed protocol and is dependent on the surgeon’s preference and judgment. Just like any reconstructive surgery, creativity is necessary on the part of the surgeon to choose the optimal repair on a patient-to-patient basis.

Isolated anterior lamellar defects:

Defects solely confined to the anterior lamella can be repaired by secondary closure, primary closure, a skin flap, a skin graft, or a cutaneo-marginal skin graft if the eyelid margin is involved. The choice is highly dependent on the horizontal length of the defect, and whether or not the lid margin has involvement.

The most straightforward repair is healing by secondary intention, which is only recommended for defects less than 1 cm in horizontal length that involve the anterior lamella and are in the central or medial canthal pre-tarsal region. Keeping the tarsus intact allows good structural support, prevents contractions that can worsen outcomes, and allow re-epithelization of the overlying skin. In the medial canthal region, there is additional structural support from the bones and the medial canthus that prevents contractures. Furthermore, grafts or flaps to the medial canthal region tend to have poor aesthetic outcomes.[1] This approach demonstrates the lowest risk of complications and is suitable for those that are poor surgical candidates. Examples include those with short life expectancy, those who cannot tolerate the risks of surgery or those with poor wound healing from radiation therapy, or poor-quality skin from conditions like xeroderma pigmentosum.[1]

Small defects confined to the skin of the upper eyelid are repairable by direct closure, which is preferable if there is excess skin adjacent to the defect. The amount of adjacent skin used to close the repair depends on the surgeon’s judgment. Great care must be done to close along the natural tension lines of the upper eyelid; this is essential to prevent devastating functional or cosmetic complications such as ectropion, eyelid retraction, eyelid distortion, or lagophthalmos.[8] Primary or secondary closure is also not preferred when there are defects involving the lid margin, therefore most lid defects aren’t simple enough to be treated with primary or secondary closure.

Once the defect is greater than 1 cm in horizontal length, other surgical repairs merit consideration. One such approach is a skin flap. Flaps are preferable to grafts due to the similarity of the skin, and the reduced risks of post-op contractures.[9] Local flaps are useful for small pre-septal defects, with the skin coming from adjacent horizontal or superior skin to respect the skin crease. Failure to do so can result in poor aesthetic outcomes. The most commonly used flaps for the upper eyelid are advancement flaps, allowing at least one border to coincide with the crease. Although preferable to skin grafts, many upper eyelid skin defects are not amenable to skin flaps because the pre-sepal skin, unlike the pre-tarsal skin, contains hair follicles. These changes occur at the orbital rim, thus limiting the amount of skin available for a flap. Hair containing skin is not suitable in the pre-tarsal region or the lid margin due to the risk of keratopathy.

Skin grafts represent a viable option for larger anterior lamellar defects. An essential concept for any graft to the upper eyelid, regardless of the layer involved, is the principle of “like-for-like.”[4] It is better to use full-thickness skin grafts retrieved from the contralateral upper eyelid. If harvested from a different region, the skin should be hairless, and any subcutaneous fat should be shaved off. Preferred alternate regions include the pre or postauricular area or the upper medial arm.[10] The best outcomes occur with pre-tarsal skin grafts. If excess pretarsal skin is present, it is preferable to undermine it and then place the flap in the pre-septal region. The graft should then undergo fixation to the tarsus. An intact tarsus is essential for eyelid reconstruction. It provides structural support and reduces contractures that would impair a good aesthetic outcome. The skin graft can be the same size as the defect but should be placed in the supraciliary region rather than the natural skin crease site. This is because the graft will form a crease near the upper border. Therefore, the cosmetic outcome will be much better if this coincides with the natural skin crease rather than appearing below the natural skin crease. The orbicularis oculi have a good arterial supply, which will enhance the survival of the graft. If the orbicularis is also missing, then the muscle should be mobilized into the defect from the surrounding region. However, if the orbicularis has to be moved into the defect, then the eye should be immobilized as much as possible for at least one week post-op with pressure dressings.[1] This prevents shearing forces on the orbicularis that would compromise vascular supply to the graft. If the surgeon is concerned about the size of the graft, another important concept is that immediate post-op ptosis should correct spontaneously with contraction and is preferable to immediate post-op upper eyelid retraction.[1]

Anterior lamellar defects that involve the eyelid margin are slightly more complicated. They are repairable by excision and closure or a cutaneo-marginal graft.[11] If the surgeon chooses excision and closure, the defect is converted into full-thickness with a pentagonal excision and then closed with primary closure. The surgeon will place a buried absorbable vertical mattress suture with superficial interrupted sutures in the tarsus. If necessary, a lateral canthotomy or superior cantholysis can be done to allow advancement of the lateral wound edge for better apposition. For significant defects or lateral defects where the incision is not closable primarily, a cutaneo-marginal graft serves for repair. These usually get harvested from the contralateral upper eyelid with a pentagonal wedge. The donor site is closed by primary intention. The tarsus and orbicularis are removed from the graft to leave the skin and margin only. The defect is then corrected using the graft. A cutaneo-marginal graft is preferable when there is a significant amount of eyelid margin involved, as this maintains a stable margin and reduces post-op corneal irritation. For any repair involving the lid margin, careful alignment must be ensured by following the landmarks of the meibomian orifices, gray line, and lash line.

Combined anterior and posterior lamellar defects:

Extensive eyelid defects that involve the anterior and posterior lamellae are more common yet more complex. A variety of techniques are available for repair, including direct closure, direct closure under tension, direct closure with myocutaneous flaps, closure with composite grafts, or tarsoconjunctival flaps. Complete upper eyelid defects are also repaired with a variety of occlusive or non-occlusive techniques.

Small posterior lamellar defects less than one-third of the eyelid length are also repairable with direct closure.[12] Similar to the anterior lamellar defects, primary closure should not be used with defects larger than one-third the length of the upper eyelid. A pentagonal wedge resection is performed, and the wound is closed using a buried absorbable vertical mattress. One difference for posterior lamellar defects is that a small superior portion of tarsus may need resection so that the lateral and medial portions of the tarsus are well opposed to the sutures. A careful surgical technique is required to prevent a notched appearance to the lid margin. Correct alignment is ensured by using the meibomian orifices, the gray line, and the lash line as landmarks.[1] As with the repair of an anterior lamellar defect, it is crucial to consider the pre-tarsal and pre-septal eyelid separately for a good cosmetic outcome. The means for achieving this is through creating a skin crease incision between the planned tarsal and septal portions of the eyelid. The tarsal portion of the eyelid then gets closed directly, and the natural skin crease will form to create a cosmetically acceptable outcome.

Full-thickness defects that involve one-third to one-half of the eyelid length are repaired with a myocutaneous flap; this is because these defects still have good residual tarsus, so don’t need a distal source for structural support. The source of the flap is typically the lateral canthus or the zygomatic area. The lateral canthus is released so that the defect can be filled medially. Care must be taken to avoid damaging the lacrimal gland and ductules during the harvesting of the flap. The most common technique is a “Tenzel flap” that has a two-step curvature. The first part curves downward, following the natural curve of the orbital rim, then the second part curves upward. Extreme care must be taken to avoid a very steep curvature to the upward portion of the flap; otherwise, there is a significant risk of upper eyelid retraction. Furthermore, the flap is elevated in a sub orbicularis plane until the orbital rim and then in a subcutaneous fashion. This technique avoids the risk of nicking the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve. The flap is fixed laterally at the orbital rim once it is certain that that the wound is closable without too much tension. After fixation of the flap at the orbital rim, the wound gets closed directly. The surgeon must reform the lateral canthus with a buried and absorbable suture, which prevents drooping of the upper eyelid in the setting of reduced muscle tone.

Another type of graft for full-thickness defects one-half to one-third the length of the upper eyelid is a composite graft called a tarsomarginal graft. It contains the lid margin and adjacent tarsus only and is dependent on a vascularized anterior lamella. The donor site is typically the contralateral upper eyelid, but the lower eyelid is an option if there is a lot of excess tissue.[13] The donor and recipient sites are slightly different than the myocutaneous flaps discussed earlier. If a temporal defect requires repair, then a nasal donor site of the contralateral eyelid is preferred, and a temporal donor site is preferred to repair nasal defects.[13] The reason that this type of repair is inappropriate for defects greater than one-half the eyelid length is that the donor site has to be closed primarily. Before resection of the graft from the contralateral eyelid, the tissue is resected to leave the tarsus and conjunctiva only. The defect is fully repaired at the host site through an anterior lamellar flap. These grafts are highly successful for several reasons. First of all, cosmetic outcomes are excellent. Also, a stable eyelid margin further adds to the aesthetic outcome and prevents corneal irritation.

Local tarsoconjunctival flaps are an option for full-thickness defects greater than one-half of the eyelid. They are also useful for defects that include the eyelid margin. Extensive defects must be carefully examined to determine the amount of residual tarsus due to its critical role in providing structural support and a scaffold for repair. At least 4 mm of marginal tarsus is necessary for a successful repair. If there is insufficient tarsus at the eyelid margin, additional tarsus must be recruited as a tarsoconjunctival flap from the conjunctival fornix. The superior tarsus needs to be freed from the levator and muller muscle, then advanced to the lid margin on the conjunctival pedicle. The medial and lateral edges of the flap get fixed to the intact tarsus on either side of the defect with an absorbable suture. The approach to this flap depends on the region and surgeon preference. For example, central defects without an intact inferior tarsus and margin are repairable with an advancement flap from the superior tarsus. Any excess tarsus requires removal. The anterior lamella is then repaired using a full-thickness skin graft or myocutaneous flap.

Eyelid bridging or sharing techniques include a variety of approaches to complete eyelid defects where there is insufficient tissue to harvest a flap from the same eyelid. In these cases, a distal pedicled flap harvested from the ipsilateral lower eyelid. This technique requires occlusion of the eyelid until the pedicle of the lower eyelid is divided. The pedicle can be from the inferior, lateral, or medial lower eyelid. The most classic procedure of this type is the “Cutler-Beard” flap.[14] A full-thickness flap is harvested from the lower eyelid, inferior to 4mm below the eyelid margin to preserve the vascular supply. It is then passed over the cornea and connected to the superior defect. The flap is divided 4 to 8 weeks post-op at the level of the new eyelid margin of the upper eyelid. The flap slides back into the donor site and gets sutured to the distal border. This approach has a variety of problems affecting the upper and lower eyelids. The upper eyelid can form entropion. One eye must remain occluded for 4 to 8 weeks, which can be bothersome to patients. There is a significant risk of instability of the lower eyelid due to the laxity of the skin, post-op scarring, or disruption of the lower eyelid retractors that can occur when harvesting the flap.[1] This situation has been addressed by adding structural support between the anterior and posterior lamella of the flap. Potential sources include donor sclera, cartilage from the ear, or the Achilles tendon.[1] Other approaches have been to only advance the anterior or posterior lamella alone and then graft the remaining portion. However, earlier flap division is necessary if using only the anterior or posterior lamella and is recommended at two weeks. Due to these potential complications, it is preferred to use non-bridging techniques.

Non-bridging techniques involve using grafts or flaps to reconstruct the eyelid without a temporarily occluding lower eyelid flap. In this case, the donor tissue requires vascularization to support both lamellae. If an anterior lamellar flap is used, a posterior lamellar graft must be used to fill the remaining defect and vice-versa. If both tissues are grafted, then orbicularis must be mobilized in between the tissues to serve as a “sandwich flap.”[15] Possible grafts for posterior lamellar reconstruction include the tarsoconjunctiva, as discussed before, hard palate chondromucosa, nasal chondromucosa, or artificial tarsal substitutes.[1] These all require a vascularized anterior lamella to ensure graft survival. Artificial tarsal substitutes or auricular cartilage can also be used but are not preferable options due to their lack of a mucosal covering, which increases the risk of damage to the cornea at the host site.[1] Generally, tarsoconjunctival grafts are preferable due to the similar consistency of the tissue, but these may not be feasible if there are extensive injuries to the other eyelids as well.

If using a tarsoconjunctival graft, it should be harvested from the contralateral upper eyelid to provide the most similar tissue. The graft is taken superior from 4 mm above the eyelid margin to preserve the margin and vascular supply of the donor's eyelid. The graft fills the defect and is fixed to the remaining tarsus and either the lateral or medial canthal tendons, depending on the side that has the defect. Researchers have postulated that this approach provides morbidity to the donor site, but studies have shown this to be minimal.[16]

When there is insufficient tissue in the contralateral eyelid for tarsoconjunctival grafts, substitute tissues are potentially useful.[17] Hard palate mucoperiosteum provides tissue that is similar in consistency to the posterior lamellae. The donor tissue comes from the hard palate between the gingival mucosa and the median raphe. Submucosal fat requires removal if present. This approach has minimal complications at the donor site like bleeding, but the complications at the recipient site are of much greater concern than tarsoconjunctival grafts. These include irritation of the conjunctiva and ocular surface, keratopathy, necrosis of the overlying skin flap, or graft dehiscence. Nasal septal chondromucosa is another alternative for grafts of the posterior lamella. The non-keratinized epithelium of the nasal mucosa is much better tolerated at the host site than the hard palate. Nasal chondromucosa can even be harvested as a flap. Artificial tarsal substitutes are generally used as upper eyelid spacers when there is a tarsal defect, but the underlying conjunctiva is still intact. The protective conjunctiva negates the problem of keratopathy at the host site.

Distal peri-ocular vascularized anterior lamellar flaps are also options. Locations include sub or super brow region, paranasal and cheek area, paramedian forehead, lower eyelid, and temporal region of the forehead. The donor site is usually closed directly but may need an additional full-thickness skin graft for closure. If necessary, intraoperative tissue expanders can increase the volume of skin for the flap and help with closure of the donor site. Complications of these techniques mostly occur from using thick skin outside of the orbital rim that isn’t suited for eyelid function. Therefore, the skin may need to be thinned out, and the pedicle may have to be divided out. Despite this, the aesthetic outcomes can be unfavorable, and there is a significant risk of corneal pathology from the mechanical irritation by the hairs. These options, therefore, are not first-line but may be necessary for certain circumstances.

Alternatively, both the anterior and posterior lamellae can be grafted with the vascularized orbicularis sandwiched in between as a ‘sandwich flap.’ Generally, the skin of the anterior lamella used in the sandwich flaps is thinner; this allows a more mobile lid, which enhances cosmesis and eyelid closure. Additional advantages include a one-stage procedure, the ideal vascularity of the orbicularis that enables the survival of both grafts, and the fact that the orbicularis is easier to mobilize by itself than in a combined skin-muscle flap. Furthermore, orbicularis flaps can also be used to enhance myocutaneous flaps, as previously described.

Complications

As with surgical procedures, there are a variety of general complications and those more specific to eyelid reconstruction. Most of these complications and ways to mitigate them were already covered above. Generally, complications of upper eyelid reconstruction pertain to either the eyelids or the globe. The additional complications of upper eyelid reconstruction not previously listed are trichiasis and poor eyelid function. The most severe of all complications in this article is blindness that can occur from keratopathy.[8] There may be additional complications pertaining to the donor site for any graft or flap. Furthermore, there may be systemic complications if underlying malignancies remain. The operating surgeon must also be attentive to the psychological impact that cosmetic defects from lid defects or failed repairs can cause to patients.

Any operation can become complicated by infection or hemorrhage that can compromise the outcomes. In the setting of reconstructive surgeries, these can occur at the donor or host sites. Wound dehiscence or graft/flap failure can occur. If the lid defect repair is by primary closure, then notching of the eyelid margin can occur. Notching of the eyelid is preventable through precise surgical technique and a good approximation of the wound margins. The method for good wound approximation with a hexagonal incision appeared above. Wound dehiscence can be reduced for upper eyelid surgeries by reducing horizontal tension on the repair via techniques such as cantholysis or lateral canthotomy. Additional considerations for all types of grafts include graft hypertrophy, failure, or contraction leading to ectropion or entropion. These can occur for anterior or posterior lamellar grafts or both. Options to treat graft complications include conservative approaches such as ocular lubricants from corneal irritation, intralesional steroids, dermabrasion, or laser resurfacing. In most cases, revision surgeries are likely to be needed.

Successful eyelid positioning is a crucial part of a successful reconstruction, especially in the case of the eyelid margin. Specifically, to the upper eyelid, there is a high risk of upper eyelid retraction, which is devastating for the outcome of the surgery. The risk of upper eyelid retraction can be mitigated when using grafts by dissecting upper eyelid retractors off the graft. Ptosis is also another complication of upper eyelid reconstruction. It is preventable by correcting the level of ptosis depending on the integrity of the levator palpebrae superioris function. Extraocular nerve entrapment can occur if there has been damage to the orbital floor. This condition will lead to diplopia and ocular malalignment. A forced duction test should be performed post-op to ensure that there is no entrapment of the muscle. Conservative or surgical approaches are possible to treat ocular muscle entrapment.[18]

Hair loss is another important functional and cosmetic concern of upper eyelid reconstructions. Depending on the type of reconstruction, eyelashes, or hairs from the eyebrow can be lost. Nylon sutures to the region or tattoos can mask these, but these approaches do not adequately address the functional component. The eyelashes and eyebrows protect the lid and globe from mechanical damage due to particulate matter. Furthermore, conservative approaches are cosmetically noticeable to patients. A much better option for patients is hair grafting.[19] For eyebrows, hair typically gets borrowed from the mid occipital region of the scalp. In eyelash grafting, the surgeon can obtain hair from a similar site, but the hair is harvested slightly differently. Individual hair follicles are removed intact from the dermis and inserted into the tarsus.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Upper eyelid reconstruction can be a very complex procedure, and often requires additional healthcare professionals beyond just the operating oculoplastic or facial reconstructive surgeon. In these circumstances, the best outcomes occur when there is careful coordination by multiple healthcare professionals forming an interprofessional healthcare team. There is level 3 evidence for this in the case of defects created from tumor excision.[20]

Before excising the tumor, a pathologist is needed to confirm the histopathologic grade and tumor subtype. There needs to be a careful evaluation for local invasion or metastases to lymph nodes or distal organs. This is often done pre-operatively by a team of specialists. The tumor requires excision with completely clear margins, preserving as much eyelid tissue for reconstruction as possible. The type of reconstruction does not determine the approach to resection. Failure to do so can lead to significant patient morbidity or even mortality. The reconstructive planning includes the pathologist and surgeon who removes the tumor. Often, in the setting of non-Mohs excision, the tumor excision and reconstruction are done in the same procedure and/or by the same surgeon. In the case of eyelid defects with ocular complications, the best outcomes occur when there is coordination with ophthalmology.[21] These patients require a full ophthalmic evaluation. Furthermore, some radiosensitive tumors like Kaposi sarcoma may receive treatment with peri-operative radiation therapy. In these cases, careful coordination must take place between the reconstructive surgeon and a radiologist and/or radiation oncologist; this is essential to treating the tumor and making sure that wound healing doesn't get compromised for reconstructive approaches.

These principles also apply to eyelid defects created by trauma or congenital anomalies. Defects created due to trauma require an extensive evaluation by ophthalmology. Any trauma to the cornea or globe may need operative repair. Furthermore, these surgeries are more urgent, and, depending on the severity, are likely to take place before the reconstruction. For congenital anomalies, an extensive evaluation for other ocular defects should take place by a pediatric ophthalmologist. Moreover, there may be other comorbid systemic congenital anomalies that require management by pediatricians and a team of pediatric specialists.

Just as with any surgical procedure, effective communication must take place between the staff in the operating room. The laterality of the reconstruction and the donor sites of the grafts or flaps must be mentioned in the time out. This can prevent a significant number of medical errors. Standard pre-, intra-, and post-op measures should be in place to monitor the patient, address any emergencies, and prevent medical errors. In this regard, specialty-trained nursing staff with ophthalmology and/or plastic surgery specialties are invaluable, preparing the patient for the procedure, assisting during surgery, and providing postoperative care. These interprofessional team principles can guide outcomes and lead to better patient results. [Level 5]