Continuing Education Activity

The skeleton is the third most common site of metastatic disease after lung and liver. Most bone metastases originate from the breast, prostate or lung although kidney and thyroid tumors can metastasize to bone as well. Carcinoma travels to bone via hematogenous spread or direct invasion of bone leading to severe pain and increased risk of pathologic fracture. This review outlines the etiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, evaluation, and management of bone metastasis and shows the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to patient care.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of bone metastasis.

- Outline the clinical presentation of patients with bone metastasis.

- Explain the management and rehabilitation strategies for patients with bone metastasis.

- Describe how an interprofessional team can collaborate to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, pain control, and management of bone metastasis.

Introduction

Metastatic bone cancer, also known as secondary bone cancer, is the term used to describe tumors that originate in other tissues and spread (metastasize) to the bone. The rich arterial supply of the bone makes it a common site of metastatic spread. In fact, the skeleton is the third most common site of disease after lung and liver. Primary bone cancer is an uncommon diagnosis. In contrast, a primary bone tumor develops from the uninhibited growth of cancerous bone progenitor cells. The term primary bone cancer implies that the malignancy began within the bone itself and excludes cancers that originate in other tissues and spread (metastasize) to the bone. Secondary bone cancer is a large heterogeneous group that can be responsive to chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery. [1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Carcinoma is the most common cause of secondary bone cancer. Many bone metastases originate from disseminated breast, lung, and prostate cancer. Although, increasingly renal cell and thyroid cancer can metastasize to bone. Carcinomas are of epithelial tissue origin and go on to form the covering over solid organs and glands throughout the body. Non-epithelial cell lines produce cancers that spread to the bone. Hematologic malignancies such as multiple myeloma and lymphoma involve bone. Similarly, mesenchymal tumors such as sarcomas, can exhibit late metastases to the bone as well. [5][6][7]

Epidemiology

Bone metastases affect survival rates ranging from 6 to 7 months in lung cancer to several years in the breast (19 to 25 months) or prostate cancer (12 to 53 months). Metastases may present with a single bone lesion, oligometastatic disease, multiple bone metastases, or visceral plus bone metastases. A study by Hernandez et al. estimated the cumulative incidence of bone metastases in the United States as 2.9% at 30 days, 4.8% at one year, 5.6% at two years, 6.9% at five years, and 8.4% at ten years. Prostate cancer posed the highest risk for bone metastases (18% to 29%) followed by lung, renal, or breast cancer.

Pathophysiology

Bone metastases occur mostly through the hematogenous spread. However local invasion from soft tissue tumors is also possible. Hematogenous spread through the venous system is the predominant process of spinal metastasis. This is because lung and breast cancers metastasize preferably in the thoracic region due to the venous drainage of the breast through the azygos vein as it communicates with the plexus of Batson in the thoracic region. Prostate cancer usually metastasizes to the lumbar-sacral spine and pelvis because it drains through the pelvic plexus in the lumbar region.

A pivotal occurrence in the pathogenesis of bone metastases involves the cellular interaction between the receptors on the tumor cells (e.g., CXCR4, RANKL) and the stromal cells of the bone marrow and bone matrix. These interactions subsequently lead to the release of growth factors, cytokines (IL-6, IL-8), and angiogenic factors (VEGF) leading to tumor growth and osteoclast activation and resultant osteolysis. The predilection for bone as a site of metastases is dependent on specific tumor characteristics, and the receptive bone microenvironment termed the seed and soil hypothesis.

Secondary bony involvement can be largely classified as osteoblastic (prostate cancer) and osteolytic (breast, lung, renal cancers) or mixed (breast cancer)

Histopathology

The histopathology of bone metastases may vary considerably, even within the same tumor. A bone biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of metastatic disease when the patient has an unknown primary cancer or history of cancer without previous bone metastasis[8]. In cases where a patient has a history of multiple cancers, a biopsy can be considered to help direct systemic treatment.

History and Physical

Patients with metastatic disease often present with progressive pain or other skeletal-related events (SRE). It is not uncommon for a patient to associate an unrelated or nonspecific low energy injury with the SRE. Often, a patient is treated with pain medication and the symptoms do not completely resolve. A detailed history and physical exam can identify red flags such as night pain, unintentional weight loss, pain with weight-bearing, or an enlarging mass in the area of concern. The physician should inspect the skin overlying the area of concern for swelling, pain with direct palpation, open wounds, or skin changes/dimpling. The limb can be immobilized with a noninvasive splint to prevent the propagation of the injury or pathologic fracture. The vertebra is the most common site affected, followed by the femur, pelvis, ribs, sternum, proximal humerus, and skull.

As a result of the destruction of normal bone architecture, the following SRE should be considered when evaluating patients with suspected bone metastases:

- Bone pain: Pain associated with bone metastasis is a frequent symptom. It is typically gradual in onset and described as a dull, boring pain that is worse at night.

- Nerve root or spinal cord compression: Bone metastases causing nerve root compression can present as radicular pain different from mechanical pain.

- Spinal cord compression: As the vertebra is the most common site of metastasis, a significant complication includes spinal cord compression, which is an oncologic emergency. Metastatic spinal cord compression occurs either through pathological vertebral collapse or direct epidural extension. Patients may present initially with back pain. Limb weakness is the second most common symptom of cord compression. Sensory symptoms include paresthesia and numbness at and below the level of cord compression. Autonomic dysfunction, including bowel and bladder incontinence and impotence, is typically a late presentation. Early recognition, workup, and prompt surgical consultation are pertinent to prevent permanent neurological damage with resultant paraplegia.

- Hypercalcemia: In the setting of malignancy, this can be multifactorial and confers a poor prognosis overall. Osteolytic bone metastases are associated with 10-30% of the cases of hypercalcemia of malignancy.[9] In osteolytic metastases, enhanced osteoclastic bone resorption occurs via the RANK-RANKL signaling pathway that leads to the release of PTHrP by tumor cells that stimulate osteoclasts and lead to unchecked bone resorption and hypercalcemia [10]. Symptoms of hypercalcemia include nausea, anorexia, abdominal pain, constipation, and mental status changes. Immediate treatment for hypercalcemia includes admission to the hospital and IV hydration.

- Pathological fractures: Bone metastases cause bone destruction increasing the patient’s risk for atraumatic or impending fracture. The presentation is dependent on the site of the disease however, constant pain is a prevalent symptom. Fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine present with pain characteristically worse with sitting or standing. Pathologic fractures result in significant morbidities resulting from pain, radiculopathy (e.g., sciatica with pelvic fracture), deformities, and immobility.

- Myelophthisis: Symptomatic anemia resulting from infiltration of the bone marrow with metastatic tumor cells. Pancytopenia may also be present in late stages.

Evaluation

It is pertinent to identify bone metastasis early, both for staging and prognostication as well as the implementation of prophylactic and treatment strategies which may lead to decreased morbidity and mortality.

Bone metastases can be characterized as osteolytic, sclerotic (osteoblastic), or mixed on imaging studies.

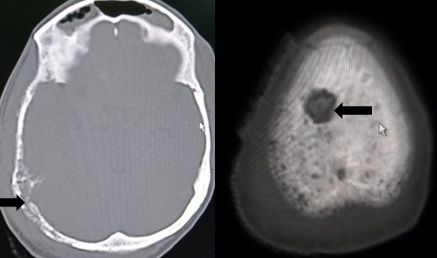

Plain Radiograph

X-rays or orthogonal radiographs are the initial imaging of choice in patients presenting with bone pain.[8] Plain films are used to assess abnormal radionuclide uptake or to detect pathological fractures.

Plain radiography best detects osteolytic lesions, but they may not be apparent until they are greater than 1 to 2 centimeters and with loss of 50% of the bone mineral content at the site of disease. Osteolytic lesions are seen as thinning of trabeculae and ill-defined margins on radiographs, while sclerotic lesions appear nodular and well-circumscribed as a result of thickened trabeculae. Plain films tend to be insensitive, especially in detecting bone metastases and with asymptomatic and subtle lesions. Progression of disease and response to therapy can be monitored with plain films and further correlation with other modalities. Sclerosis or new bone formation in osteolytic metastatic lesions is demonstrated by the sclerotic rim of reactive bone, which starts at the periphery and eventually involves the center with continued healing. Purely sclerotic lesions are more difficult to assess. Major disadvantages of plain radiographs include poor sensitivity.

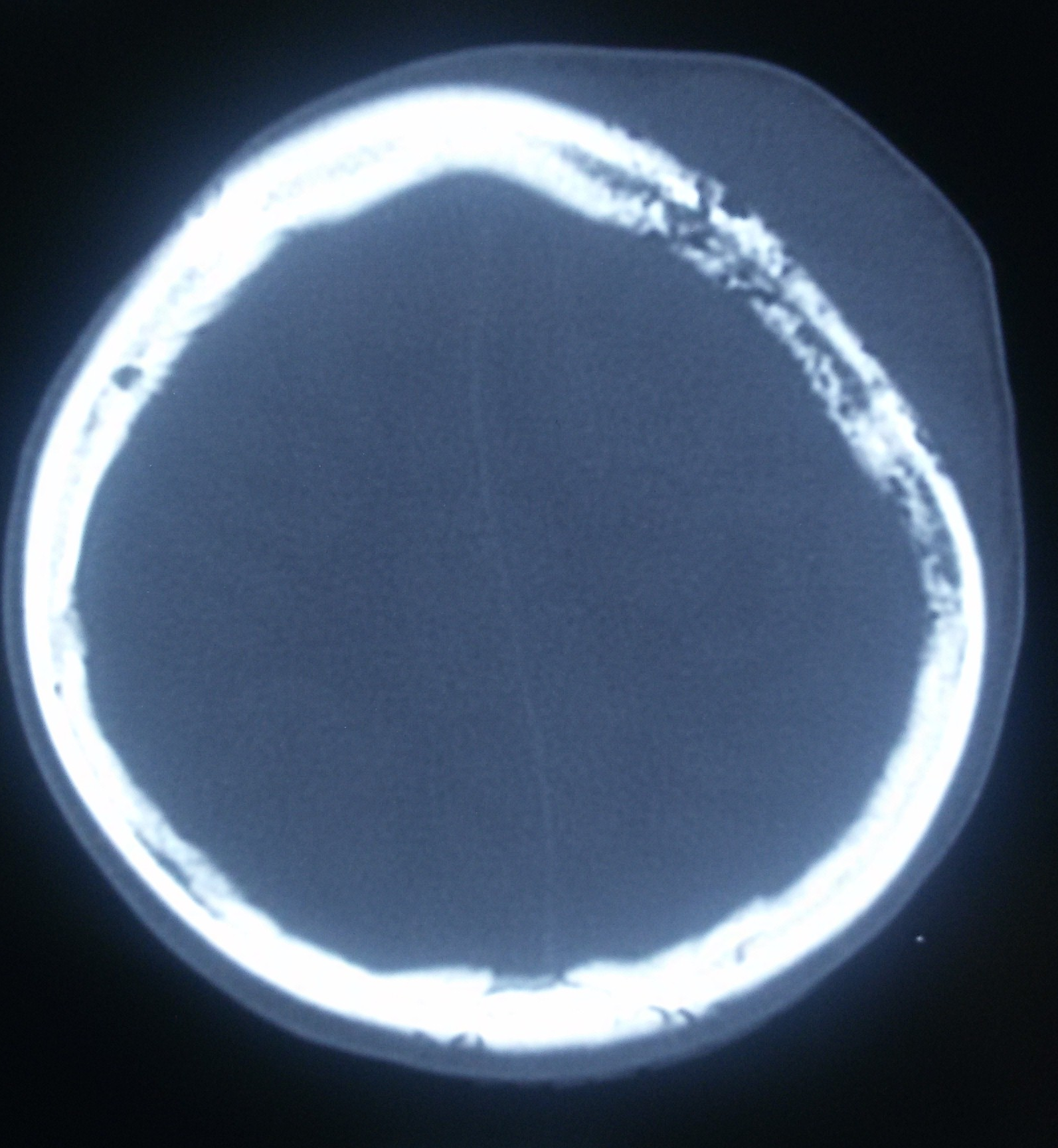

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is more sensitive (74%) than plain radiographs. It is useful in the evaluation of cortical and trabecular bone as well as in the assessment of osteolytic and sclerotic lesion. CT scan is advantageous as it can determine staging or evaluate treatment response of other organs in addition to bone and objectively assess reactive sclerosis by calculating the change in Hounsfield units. Ribs are better evaluated with CT due to the high cortex to marrow ratio. The CT scan can also assist with pre operative planning for metastatic disease, particularly around the shoulder or pelvis.

MRI

In the detection of bone metastasis, MRI demonstrates a sensitivity of 95% and specificity 90%. MRI is also more advantageous than a bone scan as it can detect marrow involvement before the development of osteoblastic lesions. It can be used with women who are pregnant and used to detect spinal cord compression. Bone metastases manifest as low T1 signal and high intensity on the T2 weighted sequence. Whole-body MRI requires 40 to 45 minutes to perform and involves short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) and/or T1-weighted sequences.

Nuclear Medicine

Nuclear medicine scans also are used to detect bone metastases using osteotropic radioisotopes; these include skeletal scintigraphy, SPECT, and PET scan.

Skeletal scintigraphy or bone scan is the most commonly used radionuclide imaging which uses 99mTc-MDP employed in the detection of skeletal metastases. Radioisotopic imaging methods depict bone metastatic lesions as areas of increased tracer uptake.

The bone scan provides the advantage of scanning the whole skeleton and has a high sensitivity (78%) therefore resulting in early diagnosis. When osteoblastic activity is prominent, the lesions are readily detected using radionuclide bone scanning. However, bone scans have a low specificity for differentiating between benign and malignant bone lesions and for the detection of predominantly osteolytic lesions. Bone scans can be used to monitor the progression of disease and response to treatment.

SPECT uses 99mTc-MDP radioisotopes uptake to detect bone lesions; however, images are acquired in cross-sectional rather than a planar fashion. SPECT has a higher specificity of 91% compared to skeletal scintigraphy.

PET is a nuclear medicine technique that uses the radiotracers 18F FDG or 18FNaF for the detection of skeletal metastases. 18F FDG PET scan identifies bone metastases based on a high glucose metabolism exhibited by neoplastic cells. PET has a better spatial resolution compared to skeletal scintigraphy. 18F NaF-PET is proven to be substantially more sensitive and specific than bone scan and SPECT for the detection of bone metastases.

Combining imaging techniques and modalities allows for improved visualization both anatomically and functionally, leading to increased diagnostic accuracy. One example of this is the 18F-Sodium fluoride (18F-NaF) PET/CT bone scanning which has a significantly greater sensitivity (100%) and specificity (97%). Other hybrid imaging techniques include SPECT/CT, PET/CT, and PET/MRI.

Blood tests can aid in supporting the diagnosis of bone metastases. Complete blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel should be obtained routinely. CBC may reveal anemia, thrombocytopenia, or pancytopenia in late stages. Serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase may be elevated due to ongoing osteolysis. Bone turnover markers are still being studied as indicators of bone resorption. Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase has been proven to elevated in patients with breast and prostate cancer with bone metastases.

Objective scoring models such as the Mirel classification system for long bones and assessment of spinal stability in addition to imaging criteria are used to determine the surgical necessity for impending pathological fractures.

Treatment / Management

The therapeutic approach to bone metastases should be a multidisciplinary approach targeted at preserving the quality of life, including pain control, minimizing SREs, and achieving local tumor control when possible. It is pertinent to consider a multitude of factors including the extent of disease spread, performance status, impending fracture, and consequence of treatment when creating the treatment plan. [11][12][13][14]

A major consideration in the treatment algorithm is providing analgesia for the debilitating pain that often occurs with bone metastases. Pain control can be initiated with NSAIDs and titrated up or used in conjunction with narcotics as needed for symptom relief. Glucocorticoids may be useful for additional pain control but should be discussed with the multidisciplinary team prior to beginning therapy as it can compromise the diagnostic accuracy of a biopsy.

Osteoclast inhibitors (bisphosphonates and denosumab) decrease morbidity and mortality associated with bone metastases as they reduce skeletal-related events and can be used to help reduce bone pain.

Local radiation for symptomatic bone metastases is a significant component of the palliative approach in providing analgesia. It is also used postoperatively to consolidate continued bone healing. External beam radiation is the standard approach for painful bone metastases and is beneficial in reducing pain by up to 50% to 80%. Several studies have proven that a single 8 Gy fraction compared to more prolonged or fractionated radiation is non-inferior; however, it may carry a higher need for pretreatment (20 % vs. 8%). Stereotactic body radiation therapy spares the normal tissue while delivering highly conformal radiation to the affected area. There are no clear guidelines on stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) use however it may be indicated over external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) in specific instances of bone metastases specifically vertebral from certain radio-resistant neoplasms.

Bone-targeted radiopharmaceutical therapy (e.g., beta-emitting agents strontium-89, alpha-emitting radium-223) provides the specific advantage of treatment of diffuse pain associated with osteoblastic bone metastases. It is typically used in bowel movement associated with prostate and breast cancer or for analgesia in radiation therapy for refractory pain.

Systemic chemotherapy when amenable, aimed at the primary tumor can also provide analgesia by reduction of tumor size and control of tumor spread.

Prophylactic or stabilization surgery is indicated for impending or complete fracture of the long bones to provide mechanical stability and preserve patient function. Spinal decompression and stabilization can be done to prevent spinal cord compression. In cases where the spread of the primary cancer is limited (single bone lesion), en bloc resection of the metastasis can be considered as means of local tumor control.

Local ablation via radiofrequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, and focused ultrasound (FUS) should be considered for patients with persistent pain following radiation therapy or patients with recurrent pain.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for bone metastases depends on the bone involved, but includes a primary bone sarcoma, multiple myeloma, primary malignant lymphoma of the bone, secondary or post-radiation sarcoma, and osteomyelitis.

A distinction between acute osteoporotic fractures versus metastatic fractures should be made on radiographic imaging. In osteoporosis, the cortical bone may be preserved; however, cortical bone destruction is typical with metastatic cancer.

Complications

The surgical treatment of metastatic bone cancer is complex and can result in many complications. Obtaining the correct diagnosis prior to beginning treatment is of paramount importance and can reduce the morbidity of patients. Moreover, the complications of surgery include but are not limited to

- Pain

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Damage to nerves and vessels in the surgical field that results in numbness or paralysis

- Tumor recurrence

- Tumor progression

- Death from surgical complications or disease progression

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of a patient with bone metastases requires an interprofessional approach. The therapeutic approach to bone metastases should be an interprofessional approach targeted at preserving the quality of life, including pain control, minimizing SREs, and achieving local tumor control. It is pertinent to consider a multitude of factors including the extent of disease spread, performance status, impending fracture, and side effects when creating the initial approach for the treatment of bone metastases.

A major aspect of treating bone metastases is analgesia/pain control for the debilitating pain that occurs with bone metastases. Pain control can be initiated with NSAIDs and titrated up to or in conjunction with narcotics as needed for symptom relief.

It is important to understand that many of these patients are frail and terminal and unnecessary investigations and procedures should be avoided. Comfort care or hospice care is ideal for many of these patients. A pain specialist, social worker, and a hospice nurse must be involved in the care of these patients- the aim is to ensure that the patient has a decent quality of life. The majority of patients with bone metastases are dead within 4-12 months. [15](Level V)