Definition/Introduction

The compliance of a system is defined as the change in volume that occurs per unit change in the system's pressure. In layman's terms, compliance is the ease with which an elastic structure stretches. Compliance is, therefore, a measurement of a system's elastic resistance. Pulmonary compliance (C) is the total compliance of both lungs, measuring the extent to which the lungs expand (change in volume of lungs) for each unit increase in the trans-pulmonary pressure (when enough time is allowed for the system to reach equilibrium).[1] It is 1 of the most important concepts underpinning mechanical ventilation to manage patient respiration in the operating room (OR) or intensive care unit (ICU) environment. To better understand pulmonary compliance, specific terminologies require a brief review. The following formula is useful to calculate compliance:

- Lung Compliance (C) = Change in Lung Volume (V) / Change in Transpulmonary Pressure {Alveolar Pressure (Palv) – Pleural Pressure (Ppl)}.

Transpulmonary pressure is the gradient between the inside alveolar and outside pleural pressure. It mainly measures the force of lung elasticity at each point of respiration (recoil pressure). Alveolar pressure is the air pressure inside the alveoli. Pleural pressure is the pressure of the fluid present inside the space between the visceral pleura (layer adhered to lungs) and parietal pleura (chest wall lining layer). Normally, the total compliance of both lungs in an adult is about 200 ml/ cm H2O. Physicians rely on this concept to understand some pulmonary pathologies and help guide therapy and adjust ventilator pressure and volume settings.

Issues of Concern

Types of Compliance:

For practical purposes, lung compliance measurement uses different methods. Based on the measurement method, lung compliance can be categorized as static or dynamic.[2]

- Static compliance: It represents pulmonary compliance at a given fixed volume with no airflow and relaxed muscles. This situation occurs when transpulmonary pressure equals the elastic recoil pressure of the lungs. It only measures the elastic resistance. Its measurement uses a simple water manometer, but electrical transducers are now more commonly used. In the conscious individual, achieving complete certainty of respiratory muscle relaxation is difficult. However, the compliance measurement is considered valid since the static pressure difference is unaffected by any muscle activity. In cases of a paralyzed individual as in the operating theatre, it is straightforward to measure static compliance using recordings captured through electrical transducers. Therapeutically, it serves to select the ideal level of positive end-expiratory pressure, which is calculated based on the following formula:

- Cstat = V / (Pplat – PEEP)

- Pplat = Plateau pressure, PEEP = Positive End Expiratory Pressure

- Dynamic compliance: It is the continuous measurement of pulmonary compliance calculated at each point representing schematic changes during rhythmic breathing.[2] It monitors both elastic and airway resistance. Airway resistance depends on the air viscosity, density, length, and radius of airways. Except for the radius of the airway, all other variables are relatively constant. Thus, airway resistance can undergo physiologic alteration by changes in the radius of the airway bronchus.

Compliance Diagram

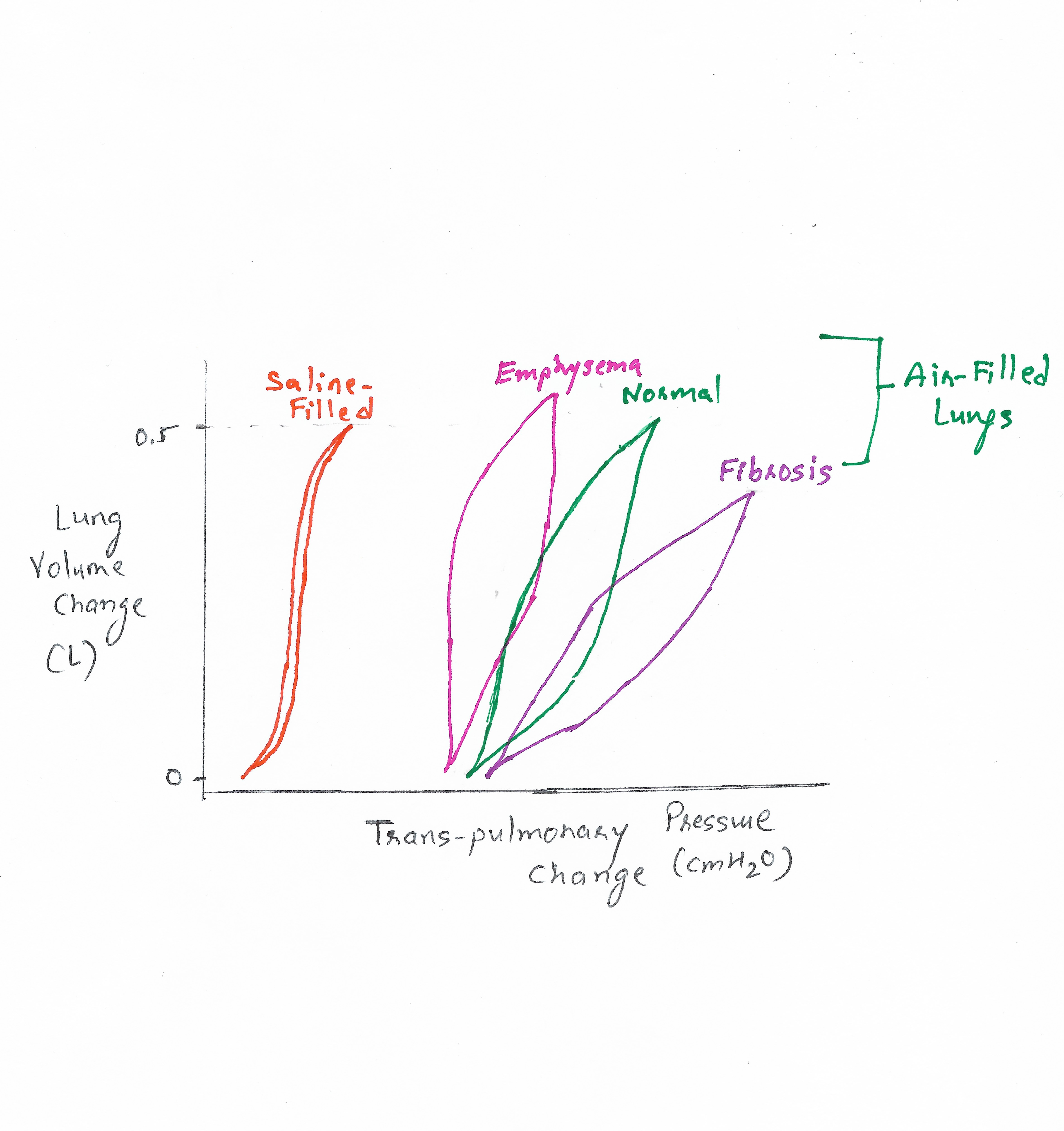

When different readings of the lung volume are taken at specific measured pressure points and then plotted on a diagram, a pressure-volume curve representing both elastic and airway resistance properties of the lung is obtained (See Image. Comparison of Lung Compliance Curves).[3] The 2 meeting points are end-inspiratory and end-expiratory; the line connecting them measures the lungs' dynamic compliance. The area between this line and the curves represents the excess work required to overcome airway resistance during inspiration and expiration. This curve is also called the Hysteresis curve.[4] You can see that the lung is not a perfect elastic structure. The pressure required to inflate the lungs is higher than the pressure necessary to deflate them.

Importance of Compliance

Lung compliance is inversely proportional to elastance. This elastic resistance is due to the elastic property of lung tissue or parenchyma and the surface elastic force. Any changes occurring to these forces could lead to changes in compliance. Compliance determines 65% of the work of breathing. If the lung has low compliance, it requires more work from breathing muscles to inflate the lungs. In specific pathologies, continuous monitoring of the lung compliance curve is useful to understand the condition's progression and to decide on therapeutic settings needed for ventilator management.[5]

Factors Affecting Pulmonary Compliance

Elastic property of the lung tissue: These result from the collagen and elastin fibers meshed inside the lung parenchyma. When the lung is outside the body system and in a deflated state, these fibers fully contract due to elasticity. When the lung expands, they elongate and exert even more elastic force, similar to a rubber band. Thus the flexibility of these fibers determines the compliance of the lungs. They could be damaged or affected by specific pulmonary pathologies.

Surface tension elastic force: One of the important concepts affecting lung compliance is the elastic property of the lung contributed to by the surface tension of the alveolar lining.[6] The image displays the compliance difference between saline-filled and normal air-filled lungs. Air-filled lungs work as a different elastic structure inside the pulmonary system. Its flexible property is not only determined by the elastic forces of the tissue but also contributes to surface tension exerted by the fluids lining the walls of the alveoli.[7] When water forms a surface with air, the water molecules demonstrate strong, attractive forces for one another, causing surface contraction. This principle is what holds a raindrop together.

Similarly, water lining the inner surface of the alveoli attempts to force air out and collapse it. This force is the surface tension elastic force. Its minimum value is 35 to 41 dyne/cm.[8] Thus, the saline-filled lung has higher compliance than the normal air-filled lung since the pressure required to expand the air-filled lung is higher than the saline-filled lungs.

Surfactant: If you measure the alveolar pressure using surface tension exerted by the lining fluid based on the Laplace law: Pressure = 2 x T (Surface Tension) / R (Radius), one notes that the pressure within the smaller alveoli would be higher than the pressure within large alveoli which collapse the small alveoli. However, in a typical scenario, this doesn't happen. It occurs where surfactants play a role.[8] A surfactant is a surface-active fluid agent secreted by type II alveolar epithelial cells lining the alveoli. It is a complex molecule containing phospholipid dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine, surfactant apoproteins, and calcium ions. They reduce the surface tension by partial dissolution. Now, returning to the mechanics, the smaller alveoli have a small surface area, which leads to a higher concentration of surfactants and, eventually, lower surface tension.[9] Due to its role in surface tension modification, it indirectly affects the compliance of the lung.

Lung volume: Compliance is related to the lung volume, considering the formula relating to volume and pressure. However, specific compliance is measured using the formula: Specific Compliance = Compliance/ FRC (Functional Residual Capacity) to eliminate this variable.

Age: This factor minimally influences compliance. Pulmonary compliance increases with age due to structural changes in the lung elastin fibers.[10]

Clinical Significance

Certain pulmonary diseases can influence changes in lung compliance. The following are pathologies that can increase or decrease lung compliance:

- Emphysema or COPD: In both of these conditions, the lung's elastic recoil property suffers damage due to a genetic cause (alfa-1 antitrypsin deficiency) or an extrinsic factor (eg, smoking). Because of poor elastic recoil, such patients have high lung compliance. Their alveolar sacs have a high residual volume, making exhaling the excess air out of the lung difficult, and patients develop shortness of breath.

- Pulmonary fibrosis: Certain environmental pollutants, chemicals, or infectious agents, as well as genetic diseases, can cause fibrosis of the lung tissue. In fibrosis, lung elastin fibers are replaced by collagens, which are less elastic and decrease the lung's compliance. Such patients need to breathe harder to inflate more rigid lung alveoli.

- Newborn respiratory distress syndrome: Usually, surfactant secretion begins between the sixth and seventh months of gestation. Premature newborns have little or no surfactant in the alveoli when they are born, and their lungs have a significant tendency to collapse. As described earlier, surfactant helps reduce surface tension, thereby increasing lung compliance. An absence of the surfactant leads to a decrease in pulmonary compliance, and this condition is called newborn respiratory distress syndrome. It is fatal and requires aggressive measures by continuous positive pressure breathing.

- Atelectasis /ARDS: Atelectasis is the collapse of lung alveoli and usually occurs in the dependent parts of the lungs. Following operative anesthesia, this could be 1 of the potential complications. In the case of atelectasis, pulmonary compliance decreases due to a decrease in lung volume and requires higher pressure to inflate the alveoli. Obtaining a compliance curve, oximetry, and arterial gas analysis is useful in ICU monitoring.[11]