Continuing Education Activity

Hydrocephalus is the symptomatic accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid inside the cerebral ventricles. It has complex pathogenesis and different causes. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of hydrocephalus and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of hydrocephalus.

- Describe the appropriate evaluation of hydrocephalus.

- Outline the management options available for hydrocephalus.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance health care and improve outcomes for patients with hydrocephalus.

Introduction

Hydrocephalus is the symptomatic accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) inside the cerebral ventricles.[1] This accumulation may be due to obstruction in the normal flow of the CSF, or to problems with absorption into the venous system by the Pacchionian arachnoid granulations, or due to excessive production of CSF. Dandy first describes hydrocephalus as communicating and non-communicating (obstructive) in early 1913, and since then, many more classifications were proposed. In adults, there are four different types; obstructive, communicating, hypersecretory, and normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). Congenital or developmental hydrocephalus is often present at birth and is often part of a genetic syndrome or spinal dysraphism.

Surgical treatment with a ventricular shunt placement is the first treatment option. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) and choroid plexus cauterization are possible options in suitable forms of hydrocephalus. Acute hydrocephalus without prompt treatment can result in brain herniation and death. In children, hydrocephalus has a mortality rate of 0 to 3% depending on the duration of the follow-up.[2]

Etiology

Obstructive hydrocephalus develops from a block in CSF pathways. The obstruction most commonly occurs at the foramina Monro, the aqueduct of Sylvius, the fourth ventricle, and foramen magnum, but most tumors with a significant size can obstruct at any point of CSF pathways. Some of the most frequent tumors associated with hydrocephalus are ependymoma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, choroid plexus papilloma, craniopharyngioma, pituitary adenoma, hypothalamic or optic nerve glioma, hamartoma, and metastatic tumors. Posterior fossa tumors are commonly associated with the development of hydrocephalus.

Communicating hydrocephalus is caused by impaired absorption of CSF. The most common causes are post hemorrhagic or post-inflammatory changes. Subarachnoid hemorrhage accounts for one-third of these cases by blocking CSF absorption at the arachnoid granulations.[3] Meningitis, especially bacterial, can be complicated with hydrocephalus. Head trauma in the industrial world is a significant contributor to hydrocephalus in adulthood.

Hypersecretory hydrocephalus is caused by an overproduction of CSF, most likely due to plexus papilloma or rarely a carcinoma. These tumors are more common in children.

Normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a type of communicating hydrocephalus with increased incidence in older age with a not fully understood pathogenesis. Impaired CSF dynamics cause it with slight or no increase in intracranial pressure (ICP).[4]

Prenatal hemorrhage or infection can cause hydrocephalus. Some genetic forms of hydrocephalus may not be evident at birth. Almost 10% of all cases of hydrocephalus in newborns is due to brainstem malformation with stenosis of the cerebral aqueduct. Dandy-Walker malformation will be the cause in 2-4% of hydrocephalus in this age group. Arnold-Chiari type 1 and type 2, agenesis of the foramen of Monro, Bickers-Adams syndrome are common syndromes in newborns with hydrocephalus.[5][6]

Epidemiology

Hydrocephalus is most common in infancy secondary to congenital malformations and from intraventricular hemorrhage in premature babies. Late in life, it presents another peak due to NPH cases. The overall global prevalence of hydrocephalus is approximately 85 per 100,000 individuals with a significant difference between different age groups; 88 per 100,000 for the pediatric population and 11 per 100,000 in adults.

The prevalence in the elderly population is much higher, somewhere around 175 per 100,000, and more than 400 per 100,000 for those more than 80 years old due to the high incidence of NPH later in life. Africa and South America have higher hydrocephalus prevalence.[7] Infantile hydrocephalus prevalence is between 1 and 32 per 10,000 births.[8] Both genders are generally equally affected.

Pathophysiology

CSF is chiefly produced by the choroid plexus, which is located within the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles. It travels through the ventricular system from the lateral ventricle to the third ventricle via the foramen of Monro, from third to the fourth ventricle via the cerebral aqueduct or aqueduct of Sylvius. It leaves the fourth ventricle through two lateral foramina of Luschka and median foramen of Magendie to enter basal cisterns, and part of it continues to flow around the spinal cord and in the central canal of the spinal cord.

The main sites of CSF absorption are arachnoid granulations that projects into dural venous sinuses, especially superior sagittal sinus. CSF is absorbed into the venous sinuses and enters systemic circulation. The average CSF volume is approximately 150 ml, and the daily production is about 500ml. This means that the total CSF volume is replaced three times per 24hours.

CFS flows slowly from sites of production to the sites of absorption according to the “bulk flow” model. Any physical or functional obstruction within the ventricular system, subarachnoid space, or venous sinuses can be a reason for developing hydrocephalus. An obstructive lesion or gliosis can block CSF flow within the ventricular system. Inflammation or scarring of subarachnoid space or elevated venous pressure within the venous sinuses can impair CSF absorption into the systemic circulation.[9][10]

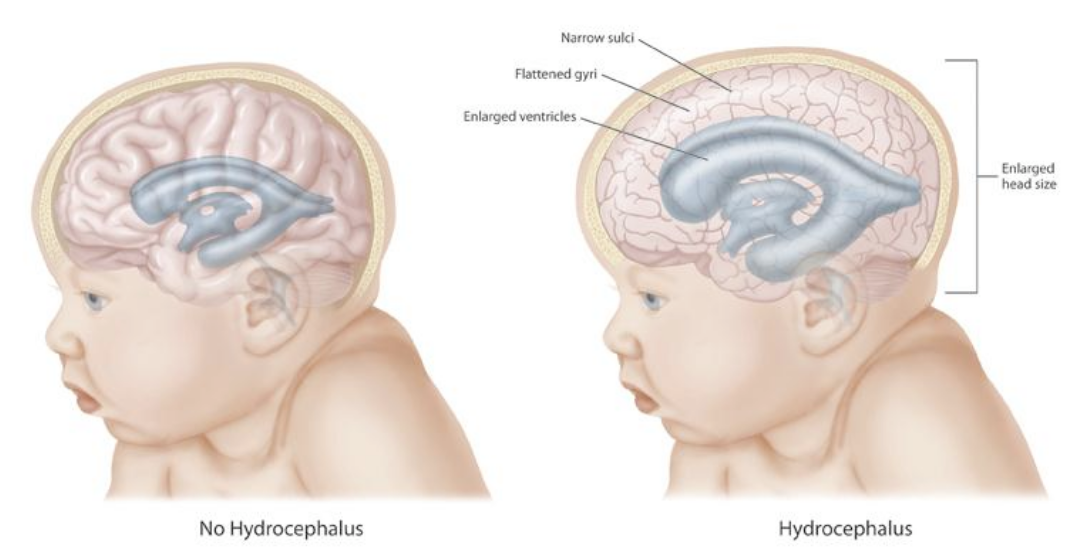

According to the Monro-Kellie doctrine, the total volume of the brain, CSF, and blood within the skull is constant. An increase in one compartment must accompany a decrease in volume in another compartment; otherwise, the pressure within the head will be increased, as happens in hydrocephalus. Increased ICP results in transependymal extravasation of CSF into the brain tissue causing brain damage and pressure-induced atrophy.[11]

History and Physical

The diagnosis of hydrocephalus is usually made using a combination of clinical signs, radiological imaging, and CSF pressure readings. Clinical features of hydrocephalus are influenced by the patient’s age, cause, location of the obstruction, duration, and rapidity of onset.

Acute hydrocephalus is a life-threatening condition and can result in brain herniation, transtentorial herniation of temporal lobe or herniation of the cerebellum into the foramen magnum, with the clinical picture of a dilated and nonreactive ipsilateral pupil, autonomic dysfunction, loss of brain stem reflexes and coma. It requires immediate neurosurgical intervention to relieve the pressure.[12]

Congenital hydrocephalus is usually present at birth. An unusually large head is a significant sign of congenital hydrocephalus. There are many more symptoms associated with congenital hydrocephalus like tense and bulge fontanelle, a disjunction of sutures, thin and shiny scalp with prominently visible veins, stiff arms, and legs prone to contractions, “the setting sun” outlook (pupils of the eyes may be close to the lower eyelid), breathing difficulties, poor feeding, the unwillingness of the infant to bend or move their neck or head, delayed developmental stages. A “cracked pot” sound on percussion of the skull is the so-called Macewen sign.

Patients may present with delayed growth and sexual maturity, high-pitched cry, irritability or drowsiness or both, possible vomiting and seizures. Failure of upward gaze is due to pressure on the tectal plate and is of supranuclear origin. In severe untreated forms of hydrocephalus, other elements of dorsal midbrain syndrome (Parinaud syndrome) may be seen.

Acquired hydrocephalus can occur at any age. Symptoms include headache, neck pain, nausea, explosive vomiting, drowsiness, lethargy, irritability, seizures, confusion, disorientation, blurred vision, diplopia, urinary and bowel incontinence, gait instability, balance problems, lack of appetite, personality changes, and memory problems.

The classic Hakim triad of NPH consists of gait problems, dementia, and urinary incontinence. Signs and symptoms of NPH may take months or years to develop. The classic gait impairment consists of a wide-based gait. With disease progression, it may lead to the point of apraxia; patients may not know how to take steps. Muscle strength is usually normal, but reflexes may be increased with or without Babinski response. Frontal release signs may be present at late stages, including sucking and grasping reflexes.

Evaluation

Genetic testing and counseling might be recommended in congenital forms of hydrocephalus.

CSF analysis could be done to help with the diagnosis and to exclude residual infection.

X-rays of the skull may show erosion of sella turcica, or so-called "beaten copper cranium" appearance, but are seldom helpful or indicated with the availability of better imaging techniques.

Ultrasonography through anterior fontanelle may be used in infants for evaluating the ventricular system and progression of hydrocephalus.

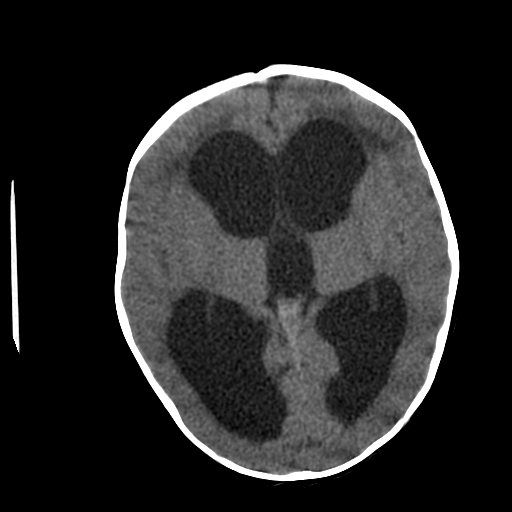

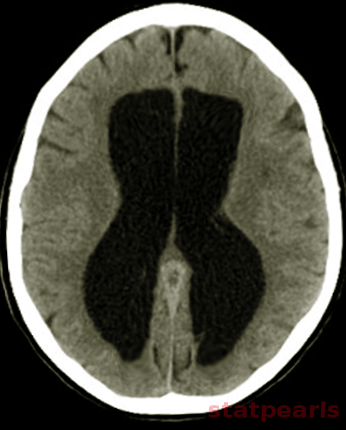

Neuroimaging plays a central role in confirming the diagnosis in suspected cases, identifying the cause and possible treatment. In cases of acute hydrocephalus, an emergency head computed tomographic (CT) scan is the first option to assess the ventricular size. Transependymal exudate can be visualized as periventricular hypoattenuation on the brain CT scan. Ballooning of frontal horns of lateral ventricle and third ventricle creates the so-called "Mickey Mouse" sign. It may indicate an aqueductal obstruction.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is the study of choice as it shows better the posterior fossa structures, can differentiate between brain tumors and degenerative diseases and can differentiate NPH from cerebral atrophy. Transependymal exudate can be visualized as periventricular hyperintensity on T2 and FLAIR sequences. CSF extravasation must be differentiated from age-related changes of periventricular white matter. Such changes are usually less than 10mm in diameter on axial cross-sectional images, and their thickness decreases from anterior to posterior.[13][14][15] On the sagittal views, the corpus callosum can be pushed up.[16][17]

In cases of chronic hydrocephalus, temporal horns may not be so prominent. Corpus callosum may be atrophied in these cases as well, but the neurodegenerative disease should be excluded. CSF stroke volume measurements in the cerebral aqueduct can be done using the MRI cine technique, but these measurements don't appear to be useful in predicting response to shunting.[18]

Radionuclide cisternography is a method used in assessing NPH and prognosis about possible shunting. This test has low sensitivity and is not commonly used.[19]

Treatment / Management

Hydrocephalus, if left untreated, can cause permanent brain damage, physical and mental impairment, and death. Initial treatment is directed to the etiology. In cases of intraparenchymal hemorrhage or tumors, surgical evacuation may resolve the hydrocephalus. When hydrocephalus persists, treatment is surgical with the insertion of a ventricular shunt.[20] The shunt moves CSF to another part of the body where it can be absorbed. With treatment, many patients have healthy lives with few limitations.

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt is the most common type of shunt. It usually drains CSF from the lateral ventricle to the peritoneal cavity; in children, it has the advantage that the distal peritoneal part may be left long and will not require changing during the growth of the child. The other common type is a ventriculoatrial shunt (VA) shunt. It shunts CSF through the jugular vein and superior vena cava into the right atrium. It’s mostly used in patients with abdominal abnormalities like peritonitis, after extensive abdominal surgery, or morbid obesity. Ventriculo-pleural shunt is a second line option only if the treatments mentioned above fail. A lumboperitoneal shunt is considered in cases of pseudotumor cerebri. Historically, in cases of acquired obstructive hydrocephalus, a shunt of choice was a Torkildsen shunt. It shunts the ventricles to the basal posterior cisternal space.

There are alternatives to shunting that may be considered. Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) opens the floor of the third ventricle to permit the CSF in the third ventricle to enter the prepontine basal cistern. ETV is commonly used in cases of aqueductal stenosis to prevent a permanent shunt; however, the result in very young infants is not good. Also, results are not good in patients with long-standing shunted obstructed hydrocephalus as the arachnoid granulations had lost the absorptive capacity. Choroid plexus coagulation can be used for cases over-production of CSF. Repeat lumbar punctures can be done in cases of communicating hydrocephalus if it’s considered that spontaneous resorption is likely to occur.

Acute hydrocephalus is a medical emergency. For those cases where a shunt can not be placed urgently, an anterior fontanelle ventricular tap may be performed in infants. In adults and children, placement of external ventricular drain is the most common procedure performed in these cases. Lumbar puncture in posthemorrhagic and postmeningitic hydrocephalus is an option.

Premature infants with posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus may improve with serial fontanelle taps. The majority of patients with a posterior fossa tumor who present with hydrocephalus do not require a permanent shunt. A ventriculostomy may be placed temporarily preoperative or intraoperative to help for the tumor resection and removed when not needed. Acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, decreases CSF secretion by the choroid plexus and hence used in the treatment of hydrocephalus. It is mostly used in pseudotumor cerebri.

Differential Diagnosis

Hydrocephalus presentation mimics many other diseases; the following differential diagnosis should be considered when evaluating a patient with hydrocephalus.

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) (pseudotumor cerebri): Intracranial pressure is elevated, but there is no identifiable pathology[21][22]

- Age-related changes[23][24]

- Secondary atrophy: Autoimmune diseases, HIV infection, chemotherapy[25][26]

- Brainstem gliomas

- Frontal lobe epilepsy

- Frontal lobe syndromes

- Intracranial hemorrhage

- Migraine headache

- Primary CNS lymphoma

- Pituitary tumors

- Acute subdural hematoma

- Subdural empyema

Prognosis

Prognosis largely depends on the cause of hydrocephalus. Half of the patients with severe intraventricular hemorrhage may require definite treatment. In children, after posterior fossa surgery, around 20% will require permanent shunting.

There are numerous, sometimes controversial criteria trying to predict the success of shunting in cases of NPH. It is considered that if gait disorder precedes mental disturbance, the chance of improvement with shunting is more than 77%. Another criterium is the response to a single lumbar puncture or external lumbar drain. Improvement of symptoms after a single lumbar puncture with 40-50 ml of CSF drained or after the lumbar drain is considered a positive predictive value for shunt success. Persistent ventricular activity 48 to 72 hours after isotopic cisternography gives more than a 75% chance of relieving the symptoms with shunt placement.

Complications

Brain damage caused by hydrocephalus can be significant and depends on multiple factors. Newborns with severe advanced hydrocephalus at birth will likely have brain damage and physical disabilities. Patients with less severe hydrocephalus who receive adequate treatment may have a relatively healthy life. Complications are associated with hydrocephalus progression, medical treatment, and surgical procedure.

- Visual changes

- Temporal lobe herniation

- Cognitive dysfunction

- Incontinence

- Gait problems

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Metabolic acidosis

- Shunt obstruction

- Shunt disconnection

- Under shunting

- Over shunting

- Subdural hematoma

- Subdural hygroma

- Seizures

- Extraneural metastases

- Hardware erosion

- Peritonitis

- Inguinal hernia

- Perforation of abdominal organs

- Intestinal obstruction

- Volvulus

- Ascites

- Septicemia

- Endocarditis

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Radiculopathy and arachnoiditis (lumboperitoneal shunts)

Consultations

The evaluation and management of hydrocephalus require a multidisciplinary approach; many specialties are involved in the care of such patients.

- Neurologists

- Neurosurgeons

- Neurorehabilitation specialists

- Ophthalmologists

- Pediatrician

Deterrence and Patient Education

At the clinics, the distal (peritoneal or atrial) catheter of the patients has to be evaluated for adequate length and revised accordingly. Knowing the signs of increased ICP, shunt malfunction, and infection is mandatory for patients and their families to look for emergent medical support. Scheduled periodic shunt reevaluations are necessary to evaluate for evidence of shunt malfunction, shunt disconnections, short peritoneal catheter, or adjustment of medications. Patients should be careful not to damage the superficially positioned valve and tubing system by trauma or by continuous scratching of the skin. Some patients require antibiotic prophylaxis for dental or other invasive procedures or diagnostic tests to prevent shunt infection.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Hydrocephalus had complex pathogenesis and multiple causes.

- There are four main types of hydrocephalus: obstructive, communicating, hypersecretory, and NPH. Hydrocephalus may be classified as congenital and acquired.

- Most tumors can obstruct the ventricular system and cause hydrocephalus. Removal of the tumor usually resolves the hydrocephalus.

- In children, hydrocephalus is often part of a genetic syndrome.

- The primary treatment for hydrocephalus is surgical with a ventricular shunt placement and CSF diversion. ETV and plexectomy are options in certain types of hydrocephalus.

- Acute hydrocephalus is an emergency.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A multidisciplinary team approach is crucial in the treatment of hydrocephalus, especially in children. Their health care needs are extended beyond childhood and adolescence. Health care transition is a process of leaving the pediatric and entering the adult health care system, but many families and patients face this transition period unprepared. Best practices are identified, and consensus recommendations are provided to facilitate this challenging period. The multidisciplinary team involving a pediatrician, neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist, and rehabilitation specialist offers the patient with integrated care for a good outcome.