[1]

Alg VS, Sofat R, Houlden H, Werring DJ. Genetic risk factors for intracranial aneurysms: a meta-analysis in more than 116,000 individuals. Neurology. 2013 Jun 4:80(23):2154-65. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318295d751. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23733552]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[2]

Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, Rinkel GJ. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Neurology. 2011 Jul:10(7):626-36. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70109-0. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21641282]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[3]

Etminan N, Rinkel GJ. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: development, rupture and preventive management. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2017 Feb 1:13(2):126. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.14. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28145447]

[4]

Chalouhi N,Hoh BL,Hasan D, Review of cerebral aneurysm formation, growth, and rupture. Stroke. 2013 Dec

[PubMed PMID: 24130141]

[5]

Samuel N, Radovanovic I. Genetic basis of intracranial aneurysm formation and rupture: clinical implications in the postgenomic era. Neurosurgical focus. 2019 Jul 1:47(1):E10. doi: 10.3171/2019.4.FOCUS19204. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31261114]

[6]

Texakalidis P, Sweid A, Mouchtouris N, Peterson EC, Sioka C, Rangel-Castilla L, Reavey-Cantwell J, Jabbour P. Aneurysm Formation, Growth, and Rupture: The Biology and Physics of Cerebral Aneurysms. World neurosurgery. 2019 Oct:130():277-284. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.093. Epub 2019 Jul 16

[PubMed PMID: 31323409]

[7]

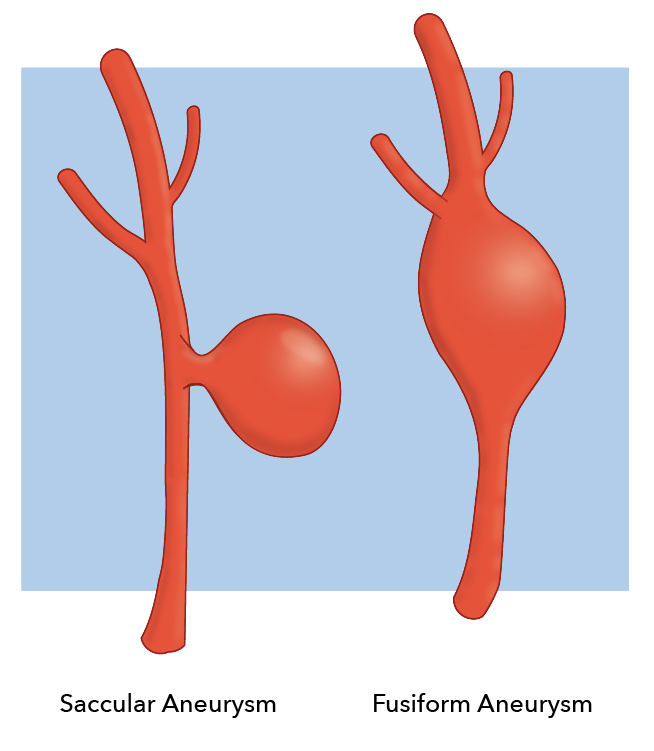

Yong-Zhong G, van Alphen HA. Pathogenesis and histopathology of saccular aneurysms: review of the literature. Neurological research. 1990 Dec:12(4):249-55

[PubMed PMID: 1982169]

[8]

Aktham A, AbdulAzeez MM, Hoz SS. Surgical Intervention of Intracerebral Hematoma Caused by Ruptured Middle Cerebral Artery Aneurysm in Neurosurgery Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq. Neurology India. 2020 Jan-Feb:68(1):124-131. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.279677. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32129261]

[9]

CROMPTON MR. Intracerebral haematoma complicating ruptured cerebral berry aneurysm. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1962 Nov:25(4):378-86

[PubMed PMID: 14023947]

[10]

Wu X, Chen X, Zhu J, Chen Q, Li Z, Lin A. Imaging detection of cerebral artery fenestrations and their clinical correlation with cerebrovascular diseases. Clinical imaging. 2020 Jun:62():57-62. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.01.012. Epub 2020 Jan 15

[PubMed PMID: 32066034]

[11]

Fisher CM, Roberson GH, Ojemann RG. Cerebral vasospasm with ruptured saccular aneurysm--the clinical manifestations. Neurosurgery. 1977 Nov-Dec:1(3):245-8

[PubMed PMID: 615969]

[12]

Wang JW, Li CH, Tian YY, Li XY, Liu JF, Li H, Gao BL. Safety and efficacy of endovascular treatment of ruptured tiny cerebral aneurysms compared with ruptured larger aneurysms. Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 2020 Jun:26(3):283-290. doi: 10.1177/1591019919897446. Epub 2020 Jan 13

[PubMed PMID: 31930939]

[13]

Nornes H, Magnaes B. Intracranial pressure in patients with ruptured saccular aneurysm. Journal of neurosurgery. 1972 May:36(5):537-47

[PubMed PMID: 5026540]

[14]

Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, O'Fallon WM. The natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. The New England journal of medicine. 1981 Mar 19:304(12):696-8

[PubMed PMID: 7464862]

[15]

Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Sundt TM Jr, O'Fallon WM. The significance of unruptured intracranial saccular aneurysms. Journal of neurosurgery. 1987 Jan:66(1):23-9

[PubMed PMID: 3783255]