[2]

Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights into imaging. 2016 Feb:7(1):69-76. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0454-5. Epub 2015 Dec 10

[PubMed PMID: 26661849]

[3]

Hacein-Bey L, Daniels DL, Ulmer JL, Mark LP, Smith MM, Strottmann JM, Brown D, Meyer GA, Wackym PA. The ascending pharyngeal artery: branches, anastomoses, and clinical significance. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2002 Aug:23(7):1246-56

[PubMed PMID: 12169487]

[4]

Devadas D, Pillay M, Sukumaran TT. A cadaveric study on variations in branching pattern of external carotid artery. Anatomy & cell biology. 2018 Dec:51(4):225-231. doi: 10.5115/acb.2018.51.4.225. Epub 2018 Dec 29

[PubMed PMID: 30637155]

[5]

Lengelé B, Hamoir M, Scalliet P, Grégoire V. Anatomical bases for the radiological delineation of lymph node areas. Major collecting trunks, head and neck. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2007 Oct:85(1):146-55

[PubMed PMID: 17383038]

[6]

Werner JA. [The lymph vessel system of the mouth cavity and pharynx]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 1995 Oct:74(10):622-8

[PubMed PMID: 8672202]

[9]

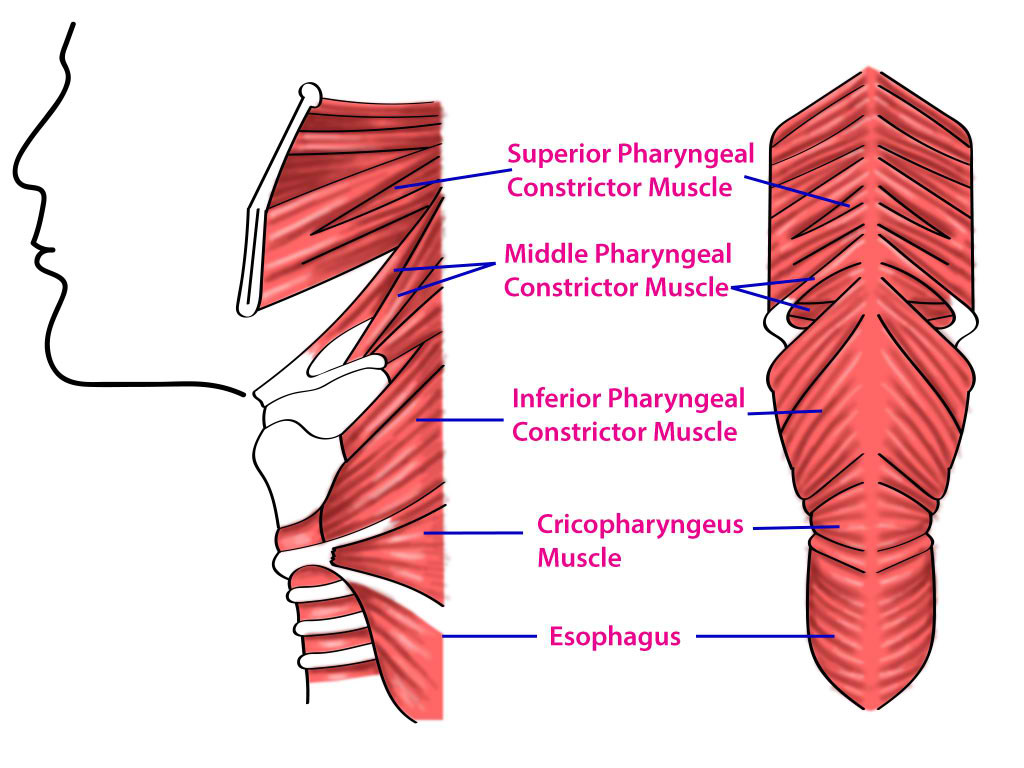

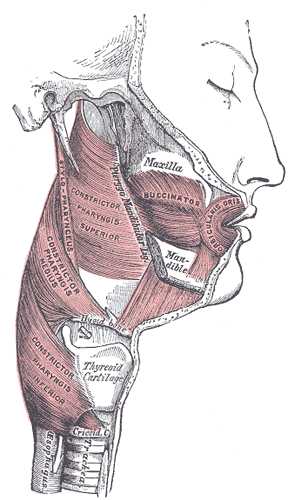

Shaw SM, Martino R. The normal swallow: muscular and neurophysiological control. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2013 Dec:46(6):937-56. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.09.006. Epub 2013 Oct 23

[PubMed PMID: 24262952]

[10]

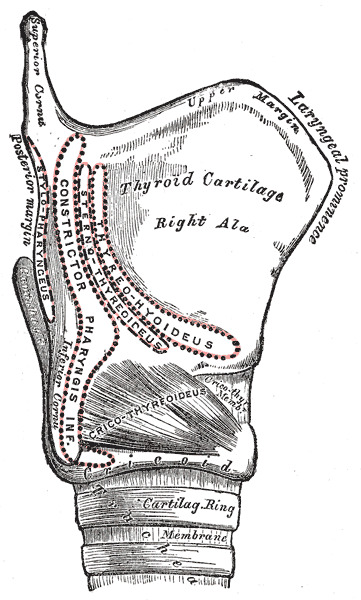

Choi DY, Bae JH, Youn KH, Kim HJ, Hu KS. Anatomical considerations of the longitudinal pharyngeal muscles in relation to their function on the internal surface of pharynx. Dysphagia. 2014 Dec:29(6):722-30. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9568-z. Epub 2014 Aug 21

[PubMed PMID: 25142243]

[11]

Murakami K, Kuroda M, Kishi K. [Variations of the constrictor pharyngeal muscles in humans]. Kaibogaku zasshi. Journal of anatomy. 1996 Dec:71(6):638-49

[PubMed PMID: 9038006]

[12]

McKenna JA, Dedo HH. Cricopharyngeal myotomy: indications and technique. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1992 Mar:101(3):216-21

[PubMed PMID: 1543330]

[15]

Hamdy S, Aziz Q, Rothwell JC, Crone R, Hughes D, Tallis RC, Thompson DG. Explaining oropharyngeal dysphagia after unilateral hemispheric stroke. Lancet (London, England). 1997 Sep 6:350(9079):686-92

[PubMed PMID: 9291902]

[16]

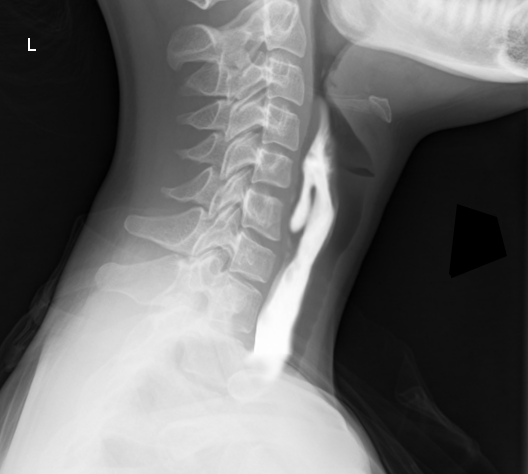

Khan A, Carmona R, Traube M. Dysphagia in the elderly. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2014 Feb:30(1):43-53. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2013.10.009. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24267601]

[17]

Drendel M, Carmel E, Kerimis P, Wolf M, Finkelstein Y. Cricopharyngeal achalasia in children: surgical and medical treatment. The Israel Medical Association journal : IMAJ. 2013 Aug:15(8):430-3

[PubMed PMID: 24079064]