Introduction

Glucose is central to energy consumption. Carbohydrates and proteins ultimately break down into glucose, which then serves as the primary metabolic fuel of mammals and the universal fuel of the fetus. Fatty acids are metabolized to ketones. Ketones cannot be used in gluconeogenesis. Glucose serves as the major precursor for the synthesis of different carbohydrates like glycogen, ribose, deoxyribose, galactose, glycolipids, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans. On the contrary, in plants, glucose is synthesized from carbon dioxide and water (photosynthesis) and stored as starch. At the cellular level, glucose is usually the final substrate that enters the tissue cells and converts to ATP (adenosine triphosphate).

ATP is the energy currency of the body and is consumed in multiple ways, including the active transport of molecules across cell membranes, contraction of muscles and performance of mechanical work, synthetic reactions that help to create hormones, cell membranes, and other essential molecules, nerve impulse conduction, cell division and growth, and other physiologic functions.[1]

Issues of Concern

The average fasting blood glucose concentration (no meal within the last 3 to 4 hours) is between 80 to 90 mg/dl. On average, postprandial blood glucose may rise to 120 to 140 mg/dl, but the body's feedback mechanism returns the glucose to normal within 2 hours. During starvation, the liver provides glucose to the body through gluconeogenesis, synthesizing glucose from lactate and amino acids.

We can summarize blood glucose regulation and its clinical significance in the following ways:

- The liver serves as a buffer for blood glucose concentration

After a meal, there is a rise in blood glucose levels, which raises insulin secretion from the pancreas simultaneously. Insulin causes glucose to be deposited in the liver as glycogen; then, during the next few hours, when blood glucose concentration falls, the liver releases glucose back into the blood, decreasing fluctuations.

Clinical significance: During severe liver disease, it is impossible to maintain blood glucose concentration.

- Insulin and glucagon work together to maintain normal glucose concentration.

High blood glucose causes insulin secretion, which concomitantly lowers blood glucose levels as glucose is driven from extracellular to intracellular. Conversely, a fall in blood glucose stimulates glucagon secretion, which in turn raises blood glucose levels.

Clinical significance: Impaired and insufficient insulin secretion leads to diabetes mellitus.

- CNS control of blood glucose levels

Low blood glucose level is sensed by the hypothalamus, leading to activation of the sympathetic nervous system to maintain glucose levels and avoid severe hypoglycemia.

- Effect of growth hormone and cortisol.

Prolonged hypoglycemia for hours and days leads to the secretion of growth hormone and cortisol that maintain blood glucose levels by increasing fat utilization and decreasing the rate of glucose utilization by cells.[2]

Cellular Level

Following are the critical steps in the utilization of glucose at the cellular level-

- Transport of glucose through the cell membrane

For glucose to be utilizable in most tissue cells, it needs to be transported across the cell membrane into the cytoplasm. Glucose cannot readily diffuse through because of its high molecular weight. Transport is made possible through protein carrier molecules; this is known as facilitated diffusion, and it takes place down the gradient from high concentration to low concentration.

There is an exception for the gastrointestinal tract and renal tubules. Here, glucose is transported actively by sodium-glucose co-transport against the concentration gradient.

- Role of insulin in glucose metabolism

The rate of glucose/carbohydrate utilization is under the control of the rate of insulin secretion from the pancreas. Normally, the amount of glucose that can diffuse in the cells is limited except for liver and brain cells. This diffusion is significantly increased by insulin to 10 times or more.

- Phosphorylation of glucose

As soon as glucose enters the cell, it becomes phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate. This reaction is mediated by glucokinase in the liver and hexokinase in most other cells. This phosphorylating step serves to capture glucose inside the cell. It is irreversible mostly except in liver cells, intestinal epithelial cells, and renal tubular epithelial cells where glucose phosphatase is present in these locations, which is reversible.

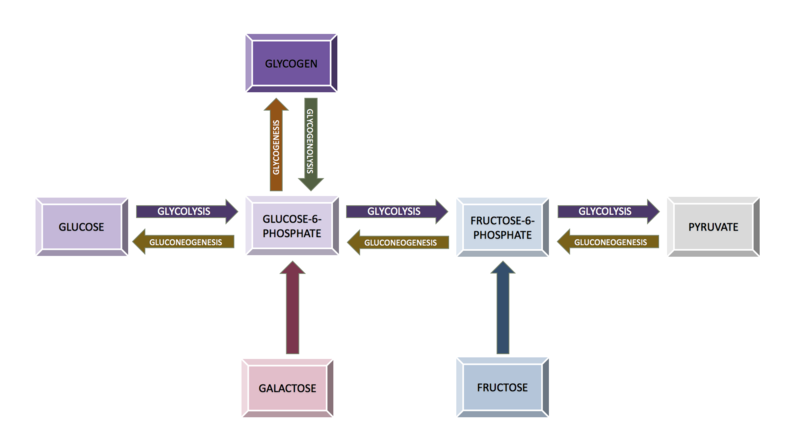

This glucose can then either be utilized immediately for the release of energy through glycolysis, a multi-step procedure to release energy in the form of ATP, or it can be stored as glycogen(polysaccharide). Liver and muscle cells store large amounts of glycogen for later utilization to release glucose by glycogenolysis, ie, the breakdown of glucose.[3]

Development

In a developing fetus, regulated glucose exposure is imperative to normal growth because glucose is the primary energy form used by the placenta. In late gestation, fetal glucose metabolism is essential to the development of skeletal muscles, fetal liver, fetal heart, and adipose tissue. Three components that are crucial to fetal glucose metabolism are maternal serum glucose concentration, maternal glucose transport to the placenta, which is impacted by the amount of glucose the fetus uses, and finally, fetal pancreas insulin production.

Fetal insulin secretion gradually increases during the gestational period. Pulsatile peaks in glucose levels are beneficial to insulin secretion; however, constant hyperglycemia down-regulates insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance.[4] In mothers with elevated serum glucose levels, adverse fetal impacts include congenital abnormalities, fetal macrosomia, and stillbirth.[5]

Organ Systems Involved

- Nervous system: The pancreas performs autonomic function through the sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of the pancreas. The brain itself also houses insulin receptors in multiple regions, including the hypothalamus, cerebellum, hippocampus, among other areas.

- Pancreas: The pancreas is behind the stomach in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The endocrine functionality of the pancreas regulates glucose homeostasis.

- Liver: Glycogenesis and gluconeogenesis are the storing and releasing of glucose, respectively. These processes occur using insulin, glucagon, and hepatocyte derived factors.

- Gut: Hormones in the gut are released in response to the ingestion of nutrients. These hormones are involved in appetite, glucose production, gastric emptying, and glucose removal.

- Adipocytes: Adipose tissue secretes adipokines, which regulate insulin release through their involvement in glucose metabolism, control of food intake, and insulin gene expression.[6]

Function

Glucose metabolism involves multiple processes, including glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and glycogenesis. Glycolysis in the liver is a process that involves various enzymes that encourage glucose catabolism in cells. One enzyme, in particular, glucokinase, allows the liver to sense serum glucose levels and to utilize glucose when serum glucose levels rise, for example, after eating. During periods of fasting, when there is no glucose consumption, for example, overnight while asleep, gluconeogenesis takes place.

Gluconeogenesis happens when there is glucose synthesis from non-carbohydrate components in the mitochondria of liver cells. Additionally, during fasting periods, the pancreas secretes glucagon, which begins glycogenolysis. In glycogenolysis, glycogen, the stored form of glucose, is released as glucose. The process of synthesizing glycogen is termed glycogenesis and occurs when excess carbohydrates exist in the liver.[7]

Glucose tolerance is regulated with the circadian cycle. In the morning, humans typically have their peak glucose tolerance for metabolism. Afternoon and evenings are a trough for oral glucose tolerance. This trough likely occurs because pancreatic beta-cells are also most responsive in the morning—similarly, glycogen storage components peak in the evening. Adipose tissue is most sensitive to insulin in the afternoon. The varied timings of fuel utilization throughout the day compose the cycle of glucose metabolism.[8]

Mechanism

Glycolysis is the most crucial process in releasing energy from glucose, the end product of which is two molecules of pyruvic acid. It occurs in 10 successive chemical reactions, leading to a net gain of two ATP molecules from one molecule of glucose.

The overall efficiency for ATP formation is only approximately forty-three percent, with the remaining 57 percent lost in the form of heat. The next step is the conversion of pyruvic acid to acetyl coenzyme A. This reaction utilizes coenzyme A, releasing two carbon dioxide molecules and four hydrogen atoms. No ATP forms at this stage, but the four released hydrogen atoms participate in oxidative phosphorylation, later releasing six molecules of ATP. The next step is the breakdown of acetyl coenzyme A and the release of energy in the form of ATP in the Kreb cycle or the tricarboxylic acid cycle, taking place in the cytoplasm of the mitochondrion.[9]

Related Testing

- HbA1c. The HbA1C value indicates a 2 to 3 month average of a patient’s glycemic control. Since the HbA1C value summarizes long-term glycemic control, it is frequently used to evaluate patients with long-standing hyperglycemia, as seen in patients with diabetes, and to forecast the risk of diabetic complications.[10]

- Fasting Plasma Glucose. Plasma blood glucose level is measured after a period of fasting, typically at least 8 hours. A value greater than 126 mg/dL is associated with diabetes.[11]

- Random Plasma Glucose. A random plasma glucose measurement is sampled sometime after dietary intake was last ingested. A value greater than 200 mg/dL is highly suggestive of diabetes.[12]

- Oral Glucose Tolerance Test. All pregnant women should receive gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) screening through an orally consumed glucose challenge and subsequent plasma blood glucose measurement.[13]

- C-Peptide. C-peptide is a quantitative measurement of beta-cell function in an individual’s pancreas. Measured via urine or serum samples, a C-peptide value aids in the evaluation and management of diabetes.[14]

- Autoantibody. The presence of autoantibodies, including islet autoantibody, insulin autoantibody, insulinoma-associated antigen-2 autoantibodies, and anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) autoantibodies, among others, are suggestive of auto-immune response as is seen in type 1 diabetes.[15][16]

Pathophysiology

Although not completely understood, Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes differ in their pathophysiology. Both are considered polygenic diseases, meaning multiple genes are involved, likely with multifactorial environmental influences, including gut microbiome composition and environmental pollutants, among others. Type 1 diabetes is the autoimmune destruction of the body’s pancreatic beta cells, which produce insulin hormone. Without the insulin hormone, the body is unable to regulate blood glucose control. Type 1 diabetes more commonly presents in childhood and persists through adulthood, equally affects males and females, and has the highest prevalence of diagnosis in European White race individuals. Life expectancy for an individual with Type 1 diabetes is reduced by an estimated 13 years.

Type 2 diabetes results when pancreatic beta cells cannot produce enough insulin to meet metabolic needs. Additionally, as adipose cells are deposited in the patient’s liver and muscle, insulin resistance becomes a prominent feature of Type 2 diabetes. Therefore, individuals with more adipose deposition, typically with higher body fat content and an obese BMI, more commonly have type 2 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is more common, as 95% of individuals with overall diabetes have Type 2 Diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is more common among adult and older adult populations; however, youth are demonstrating rising rates of type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is slightly more common in males (6.9%) than in females (5.9%). It is also more common in individuals of Native American, African American, Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander race or ethnicity.[17]

Clinical Significance

Poor glucose metabolism leads to diabetes mellitus. According to the American Diabetes Association, the prevalence of diabetes in the year 2015 was 9.4%, with people aged 65 and older forming the largest group. Every year, 1.5 million Americans receive a diagnosis of diabetes. As the seventh-highest cause of mortality in the United States, diabetes mellitus poses a concerning healthcare challenge with large amounts of yearly expenditures, morbidity, and death.

Diabetes is classified into two types-

Type 1 DM- due to deficient insulin secretion. Key features of this type are-

- Immune-mediated in over 90% of cases.

- It can occur in any age group but is most common in children and young adults.

- Circulating insulin is virtually absent, leading to a catabolic state with exogenous insulin required for treatment.

Type 2 DM- due to insulin resistance with a defect in compensatory insulin secretion. Key features of this type are-

- This condition occurs predominantly in adults but is now increasingly present in children and adolescents.

- Genetic and environmental factors combine, leading to insulin resistance and beta-cell loss.

- Treatment entails lifestyle changes and oral anti-diabetic drugs.

Uncontrolled diabetes poses a significantly increased risk of developing macrovascular disease, especially coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular disease. It also increases the chances of microvascular disease, including retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.[18]