Introduction

The neck makes the connection between the head and the torso. The neck is made up of attachments from many muscles. The neck region contains many vital structures and organs that help regulate and maintain homeostasis of the body but most importantly, the impulses and regulation from the main control center of the body.

The neck is a very complex region of the body, and one of the most critical structures in the neck are the common carotids. The common carotids serve as one of the major blood supply to the head that originates from direct projection from the aorta. Along with the common carotid giving rise to blood flow to the head and brain from its branches, the common carotid also contains vital sensory organs that help control/regulate the blood pressure through the number of impulses using the autonomic nervous system.

The protection of the structures in the anterior neck, such as the airway, esophagus, blood vessels, and nerves are from the anterior neck muscles. These neck muscles protect these vital structures, but they also help support the head and influence facial expression and mastication.

Structure and Function

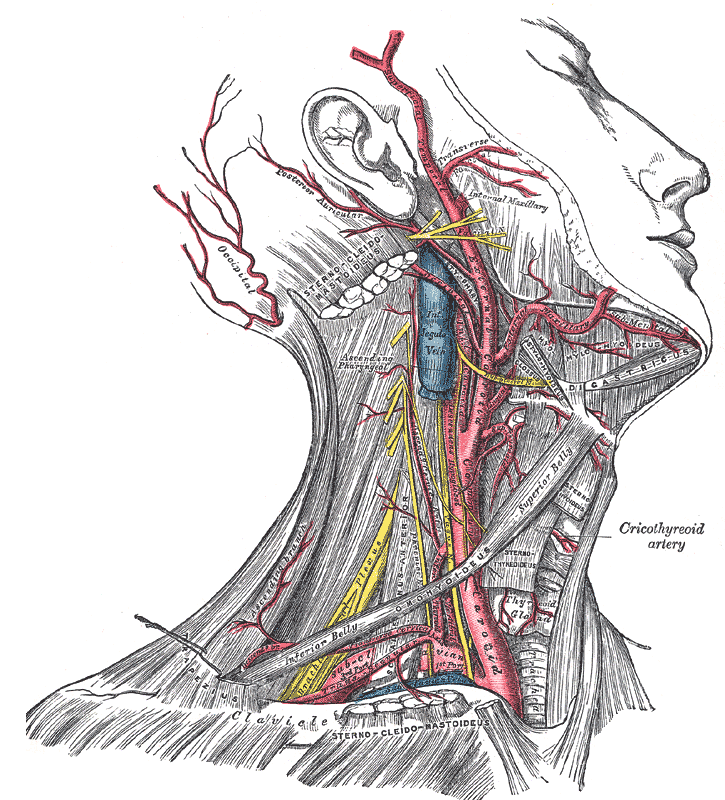

The overlying muscles protect the structures deep to them. The trachea is a midline structure that is deep to the overlying musculature. The trachea allows air to come and go into the lungs for gas exchange. Laterally to the midline and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, there lays the carotid sheath that contains the common carotid artery, internal jugular vein, cranial nerves, and deep cervical lymph nodes.[1][2] The common carotid arteries are one of the major pairs of arteries in the human body. The right common carotid artery is a branch of the brachiocephalic trunk while the left common carotid artery comes off the aorta directly. The common carotid arteries are considered large size muscular arteries. The artery is made up of three main layers. The most medial layer is called the tunica intima, and it is made up of epithelium and connective tissue. The layer superficial to the intima is the tunica media, and this layer is made up of smooth muscles. The smooth muscles provide the rigidity and facilitate pulse contraction to propel blood flow forward. The most superficial layer of the common carotids is the tunica adventitia, and this layer is made up of collagen and elastic tissue. This layer provides the flexibility and elasticity characteristics of the carotids. The characteristics of the pulsatile nature of the common carotid arteries also help propel lymph fluid in the nearby cervical lymph nodes that run close to the carotid sheath, draining the organs and structures of the head and neck.[3]

The function of the common carotid arteries is to bring oxygenated blood from the left side of the heart to the head and neck. The common carotids travel in the carotid sheath and then bifurcate into the internal carotid and external carotid arteries at the level of cervical vertebrae four (C4). At the site of bifurcation, there are sensory organs called the carotid bodies. These sensory organs play a significant role in controlling blood pressure, oxygen level, and blood pH. The receptors specific for the blood pressure are the baroreceptors; these receptors sense the stretch and increase in pressure exerted on the carotid bodies. Baroreceptors send impulses to the brain through cranial nerve IX, and the brain sends an impulse back down through cranial nerve X. The baroceptors’ impulses help influence the sympathetic nervous system to help maintain and regulate the blood pressure. The baroreceptors increase impulses when there is an increase in pressure or stretch in the carotid bodies, but when there is a decrease in stretch or pressure, the baroceptors decrease impulses to the central nervous system. The balance of blood control is carefully manipulated by the number of impulses from the baroreceptors, while the peripheral chemoreceptors respond to the increase in carbon dioxide or decrease the partial pressure of oxygen. When either of these two dissolved gases become disrupted, the peripheral chemoreceptors increase the respiratory rate to try and return the body to homeostasis.[4][5][6]

Embryology

During the development of a fetus, the head and neck region partially develops from the brachial apparatus. The brachial apparatus is broken down into branchial clefts, pouches, and arches. The clefts are made up of ectoderm, but only the first cleft will form the external acoustic meatus while the rest of the clefts will obliterate. The brachial arch is composed of mesoderm and neural crest. The arches will eventually divide into the arteries, muscles, cartilage, and bony structures in the face and neck. The brachial pouches are made up of endoderm that will develop into the organs in the head and neck. Along with the development of the structures in the head and neck, there are aortic arches. The aortic arches will eventually develop into arteries for the head, face, neck, and branches from the aorta. The first aortic arch is responsible for developing the maxillary artery, which is one of the terminal branches from the external carotid artery. The second branch is the stapedial artery, which comes off the posterior auricular artery in the adult. The third aortic arch will form the common carotid artery, which will eventually fuse with the superior branches and become the main artery that supplies blood to the superior arteries derived from first and second aortic arches.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the common carotid arteries and main arteries is from the vasa vasorum. This a small network of the capillaries that supply the lumen and the walls of the common carotid arteries.[8]

The common carotid arteries itself do not supply blood to the body, but its branches supply the head and neck regions from the external and internal carotid arteries. Following the bifurcation of the common carotid arteries, the internal carotid arteries go into the brain and supply the brain with blood via its terminal branches and contributing to the formation of the circle of Willis. The internal carotid artery branches into the anterior cerebral artery, and this supplies the frontal lobe medially and superiorly. The middle cerebral branch of the internal carotid supplies the lateral portion of the frontal lobes and the superior half of the temporal lobes. The blood supplies of the middle cerebral arteries are so vast that it even supplies some of the deep nuclei and the anterior portion of the parietal lobes.

Some of the smaller branches of the internal carotid like the posterior communicating arteries are mainly for collateral and bypass blood flow for the circle of Willis. The internal carotid artery also gives a branch off to supply the eyes as the ophthalmic arteries.

The external carotid arteries have eight major divisions that supply the head, neck, and face. As the external carotid arteries ascend the neck, it gives off a branch called the superior thyroid artery. The superior thyroid artery is vital for the muscles, organs, and structures predominantly inferior to the hyoid bone like the thyroid gland, infrahyoid muscles, and sternocleidomastoid muscle, but also the larynx above the hyoid bone. The second branch from the external carotid arteries is the ascending pharyngeal arteries. These arteries supply the middle ear, pharynx part of the oral cavity, prevertebral muscles and ascend to supply the meninges. The next branch that arises is the lingual artery that supplies the floor of the mouth and tongue. As the external carotid artery approach the mandible, it gives off the facial artery. The facial artery has multiple regions of the face, palate part of the oral cavity and tonsils, and submandibular glands that it supplies. The external carotid supplies the scalp through the next branch, which is the occipital artery. The posterior auricular artery is the last branch before the external carotid artery terminates into end branches. This artery is important in supplying the ear, scalp, cranial never VII, and parts of the scalp.[9]

The external carotid artery terminates into the maxillary artery and superficial temporal artery. The maxillary supplies many structures in the head such as the muscles of mastication, teeth and the underlying gingivae, the jaw, the dura mater, the calvaria, the tympanic membrane, and external acoustic meatus of the ear. While the superficial temporal artery supplies the scalp around the temporal region.[10]

Nerves

The common carotid artery’s baroreceptors influence the regulation of the blood pressure. The baroreceptors send impulses to the brain via the Herring nerve, which is a division from cranial nerve IX (glossopharyngeal nerve). Once the impulses reach the central nervous system, the brain will respond by sending impulses to the sympathetic nervous system to increase or decrease in impulses via the sympathetic chain to either oppose the parasympathetic or increase parasympathetic impulses. The impulses from the parasympathetic nervous system are via cranial nerve X (vagus nerve) to the sinoatrial node and atrioventricular node to regulate blood pressure. The amount of impulse from the baroreceptors to the brain directly correlates to the increase of pressure or stretch on the common carotid arteries, but when the baroreceptors increase firing this leads to a decrease in efferent impulses from the sympathetic nervous system. When the sympathetic nervous system decreases in firing, unopposed parasympathetic impulses result and the opposite mechanism occurs when there is less pressure or stretch than normally exerted on the common carotid arteries.

While the common carotid arteries use the cranial nerves to control blood pressure, the nerves innervation for the muscles in the neck is motor or sensory. The platysma muscle is innervated by the cranial nerve VII (facial nerve) and assist in facial expression. The sternocleidomastoid muscle receives innervated from cranial nerve XI (spinal accessory nerve) which is important in head-turning. As for the nerve innervation of the suprahyoid muscles are different even though when these muscle work in sync to elevate the hyoid bone. The digastric muscle is unique in that aspect that it has two muscle bellies, and each muscle belly has a different nerve innervation. The anterior belly of the digastric muscle receives innervation by a branch from cranial nerve V (trigeminal nerve), but the posterior belly gets innervated by a branch of cranial nerve VII. The trigeminal nerve innervates the mylohyoid muscle along with the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. Along with innervating the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the facial nerve also innervates the stylohyoid. As for the geniohyoid muscle, this is the only suprahyoid muscle that is innervated by cranial nerve XII (hypoglossal nerve).

The infrahyoid muscles are all innervated by the ansa cervicalis (C1-C3 nerve roots) except for the thyrohyoid muscle. The hypoglossal nerve innervates the thyrohyoid. All these muscles work in sync to depress the hyoid bone.

Muscles

The anterior structure of the neck is composed mainly of the complex network of neck muscles that protects the structures such as the trachea and common carotid arteries. The most superficial muscle is the platysma. The platysma muscles originate from the fascia above and below the neck. The platysma muscle blends in with the facial muscles. Due to the connection between muscles in the neck to muscles in the face, the platysma muscle helps with lowering the mandible and facial expression. Another superficial muscle in the neck is the sternocleidomastoid; this muscle functions to rotate the head to the contralateral side while side bending the head ipsilaterally. Along with the motion created by the sternocleidomastoid, it also protects the underlying carotid sheath and the contents within and nearby it. The sternocleidomastoid also functions to connect the head, neck, and thoracic through the attachments from the mastoid process to the sternum and clavicle.

Deep to the anterior superficial muscles, four paired muscles attach superior to the hyoid bone. These muscles are considered the suprahyoid muscles: digastric muscle, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, stylohyoid. The principal function of these muscles is to elevate the hyoid bone during speaking and swallowing. The digastric muscle has two bellies that are fused via the central tendon and originate from the mandible and attaches to the hyoid bone, allowing it to depress the mandible and elevate the hyoid at the same time during speaking and swallowing. The mylohyoid muscle extends from the inner surface of the mandible and projects to the central tendon to a fused structure called the midline raphe that attaches to the hyoid bone. The mylohyoid contributes to the depression of the mandible while elevating the hyoid bone and the floor of the mouth. The geniohyoid muscle starts from the inferior mental spines to the medial symphysis, and the stylohyoid starts from the styloid process to the hyoid bone. Both the geniohyoid muscle and the stylohyoid muscle will elevate the hyoid bone, but the geniohyoid muscle draws the hyoid bone anterior in motion while the stylohyoid pulls the bone posteriorly.

While inferior to the hyoid bone, there is another group of four paired muscles called the infrahyoid muscles: sternothyroid, sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, and omohyoid. The major function of these muscles depresses the hyoid bone and elevates the larynx to facilitate swallowing. While all the infrahyoid muscles depress the hyoid bone, the sternohyoid muscles also depress the larynx due to their shared origin from the anterior surface of the sternoclavicular joint to attach to the body of the hyoid bone. This is in contrast with the thyrohyoid muscle that elevates the larynx because it starts at the thyroid cartilage and attaches to the greater horn of the hyoid bone. The omohyoid muscle is unique because it has two bellies similar to the digastric muscle. This muscle starts from the superior border of the scapula and attaches to the body of the hyoid bone. Along with the attachment to the hyoid bone, the omohyoid muscle also serves a minor role in the protection of the carotid sheath's contents.

Physiologic Variants

The common carotid artery coming off the aorta on the left and the right common carotid artery usually comes off the brachiocephalic trunk. There are variations where the right common carotid artery comes directly from the aorta. Even rarer is the right common carotid artery originating from the right subclavian artery.[11] The most common site for bifurcation of the common carotid artery is at C4, but the use of the C4 level as a landmark may be inconsistent in different individuals. The bifurcation may be slightly higher or lower than C4.[12] The size of the internal carotid artery and external carotid artery can vary from person to person, but usually, the internal carotid artery tends to be slightly bigger. External carotid artery branches have many variations. The order of the eight branches coming off of the external carotid artery can vary greatly, but the region of blood supply stays consistent.

Surgical Considerations

The use of palpating the pulse from the common carotid artery and the sternocleidomastoid muscles as an indicator for the site of placement for a central venous catheter in the internal jugular vein. The internal jugular vein courses most superficial to the common carotid artery in the carotid sheath and deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The use of the carotid pulse help indicates the landmark area for cervical lymph node dissections. The lymph node chain in the neck follows the path close to the internal jugular vein.

Presences of severe impending occlusion of the common carotid arteries from severe atherosclerosis with neurological symptoms can indicate surgical intervention. Surgery of the common carotid arteries such as carotid endarterectomy can restore blood flow to the brain, head, neck, and face.[13]

Along with surgeries of the common carotid artery itself, procedures in the region of the arteries can be performed safely with knowledge of the location of the arteries to avoid damaging a major blood supply to the head and neck.

Clinical Significance

The common carotids arteries are the initial sign for pulse checks in adult cardiac arrest patients due to the easy accessibility. It is crucial to know the correct location for palpating the carotid pulses when a patient has arrested. To accurately assess the patient before initiating basic life support (BLS) or advanced life support (ALS). The recognition of absents pulse can help first responders to act quickly in performing life-saving measures, while the correct recognition of pulse return with sinus rhythm or complete absence of pulse may indicate the termination of BLS or ALS to reduce further harm or further futile life-saving measures.

The common carotid arteries are an essential site for a pulse check, and assessment of carotid bruits during a standard physical examination. Auscultation of the common carotid arteries showing bruits can indicate a narrowing of the lumen from atherosclerosis. The presence of atherosclerosis at the carotids can easily indicate the patient suffers from a disease of the arteries in other areas of the body. This early discovery can direct patient care toward the prevention of further atherosclerosis that could potentially prevent myocardial infarction, stroke, high blood pressure, peripheral vascular disease, and among others.[14]

Large vessel vasculitis commonly affects the common carotid arteries and its branches. The vasculitis that directly affects the common carotids right off of the aorta that presents in a young female with decrease upper extremity pulses or claudication can lead to the diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis before the patient suffers from irreversible damage.[15] While in an older female, a tender temporal region with jaw claudication can indicate a vasculitis affecting a branch of the external carotid artery suggesting giant cell temporal arteritis. The prompt diagnosis of giant cell arteritis can prevent vision loss before it affects the ophthalmic artery.[16]

Other Issues

The presence of the carotid bodies in the region of the common carotid artery bifurcation can lead to orthostatic hypotension or the resetting of irregular heart arrhythmia. The idea of increased stretch or pressure on the carotid bodies leads to a sudden drop in blood pressure and potentially syncope. Irregular heart arrhythmias such as supraventricular tachycardia can resolve by the carotid massage. The kneading of the carotid bodies causes the baroreceptors to sense an increase in stretch/pressure leading to increase signals to the brain influencing the decrease of heart rate and blood pressure. The reduction in blood pressure is through the lowering of heart rate and increased parasympathetic tone.