Continuing Education Activity

Ocular neuropathic pain is a diagnosis of exclusion which refers to the heightened perception of pain in response to normally non-painful stimuli. It usually presents without any visible objective exam findings, making it extremely difficult to identify. For this reason, it is often misdiagnosed as dry eye disease. This activity describes the etiology, epidemiology, evaluation, treatment, and management of ocular neuropathic pain. This activity also highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the recognition and management of this condition.

Objectives:

Explain the etiology of ocular neuropathic pain.

Review the presentation of a patient with ocular neuropathic pain.

Describe the current treatment options available for ocular neuropathic pain.

Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving the outcomes of patients suffering from ocular neuropathic pain.

Introduction

Ocular neuropathic pain is a diagnosis of exclusion which refers to the heightened perception of pain in response to normally non-painful stimuli. It usually presents without any visible objective exam findings, making it extremely difficult to identify.[1] For this reason, it often gets misdiagnosed as dry eye disease.

Ocular neuropathic pain may present with accompanying visible damage to tissue; however, it can also occur as a result of a physiological dysfunction of the nervous system.[1] With other corneal pathologies, the intensity of corneal pain often correlates with vital dye staining. However, in patients with ocular neuropathic pain, symptoms are severe and unaccompanied by equivalent signs, which is why ocular neuropathic pain is sometimes referred to as “corneal pain without stain” or “phantom cornea.”[2] This is the ocular analog of complex regional pain syndrome, systemic neuropathic pain, or reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Other names for this condition include, but are not limited to corneal neuropathic pain, corneal neuralgia, ocular pain syndrome, keratoneuralgia, corneal neuropathic disease, and corneal allodynia.

Ocular neuropathic pain is an important differential to consider because many patients get misdiagnosed due to its significant overlap with dry eye disease. The disparity between signs and symptoms often results in patients being dismissed or considered malingering, hysterical, or psychosomatic.[3] As demonstrated by case reports, patients with extreme cases of this condition have even committed to suicide due to the severity of chronic pain.[4] An important first step in treating ocular neuropathic pain is to communicate the belief that the condition and the symptoms are real.[2]

The objective of this article is to provide a summary of the condition and review approaches for its treatment and management, as well as increase awareness of this underrecognized disease.

Etiology

Ocular neuropathic pain can result from injury to or disease of peripheral corneal nerves.[1] The healing process results in aberrant regeneration and upregulation of nociceptors in the corneal nerves, which leads to hyper-responsivity and an increased perception of pain to ordinarily non-painful stimuli.[5] Ocular neuropathic pain may also result from a variety of systemic conditions which alter the somatosensory pathway.[1]

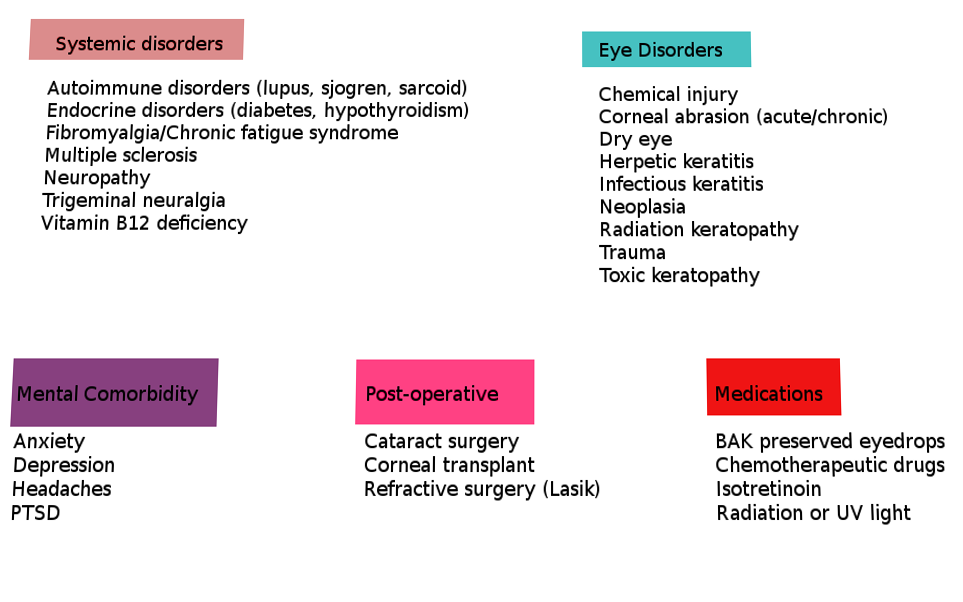

A comprehensive list of potential underlying causes that can lead to or have been associated with ocular neuropathic pain and trigger the heightened pain response to non-noxious stimuli are listed below in Table 1 (adapted from Dieckmann et al.).[1][2][6]

Epidemiology

As stated in the above table, ocular neuropathic pain has many systemic associations. The four most common are depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, and headache.[1] Following these are diabetes, celiac disease, HIV, and idiopathic small fiber neuropathies.[1]

The proportion of females with ocular neuropathic pain is higher than men.[7] Females also tend to have a higher incidence of associated conditions such as fibromyalgia and autoimmune diseases. While autoimmune diseases affect between 5 to 8% of the population, 78% of the affected are women.[7] This association may be contributory to the higher incidence of ocular neuropathic pain in women.

Pathophysiology

The human cornea is often referred to as one of the most potent pain generators in the human body.[6] Unsurprisingly, it is also among the most densely innervated tissues with approximately 7000 nerve terminals per square millimeter, making the cornea about 300 to 600 times more sensitive than skin.[6] Corneal nerves carry the sensation of touch, pain, and temperature.[8] Most of the nerves of corneal subbasal plexus are unmyelinated (C fibers) and some are myelinated (Ad fibers).

Corneal nerves detect mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli. Input is perceivable as pain or a range of dysesthesias (unpleasant abnormal sensations)[6]:

- Photoallodynia (pain sensation in response to a non-painful stimulus, light)

- Burning

- Irritation

- Dryness

- Grittiness

Pain protects tissue from injury. Detection of painful stimuli by nociceptors transmits via action potentials to higher order centers where the pain is perceived.[1] Iatrogenic damage, trauma, and inflammation of the ocular surface can result in damage to this system, which may increase the sensitivity of peripheral nerves.[1][3] This increased sensitivity, or peripheral sensitization, intensifies pain signaling. Chronic stimulation can cause sensitization of the central nervous system and thus increased awareness of pain and photoallodynia.[1]

History and Physical

Due to the complexity of mechanisms involved in ocular neuropathic pain, the subjective symptoms of corneal dysesthesia can vary significantly. Patients may describe feelings of burning, aching, boring, hot poker-like fire, foreign body, and photophobia. The symptoms may substantially affect the quality of life of the patients and may cause impaired functioning relative to activities of daily living.

The Ocular Pain Assessment Survey (OPAS) may help evaluate corneal and ocular surface pain as well as its impact on the quality of life.[6] Surveys are useful not only in diagnosing but also in monitoring the efficacy of therapeutic approaches.[3]

Patients may also present with blepharospasm that developed due to chronic corneal nociceptor hyperactivity.[2][9]

Evaluation

To verify a diagnosis of ocular neuropathic pain, viewing the cornea in vivo using a confocal microscope allows for detection of abnormalities of the corneal nerves.[6] Specific characteristics of the instrument also enable it to be a tool to differentiate among various causes of perceived ocular pain, gauge the relative contributions of central versus peripheral mechanisms, and monitor the success or failure of treatment.[10]

The use of esthesiometers can be used for the detection of mechanical nociceptor responses and allow quantification of nerve fiber functionality.[6] Findings of morphological changes and hypersensitivity of corneal nerves in patients with chronic symptoms suggest the presence of ocular neuropathic pain.[5]

Since the above diagnostic methods are not readily available to a majority of practitioners, ocular neuropathic pain is often considered a diagnosis of exclusion.

Patients may demonstrate an exaggerated pain response to touch, air, and drops. A thorough case history is paramount to revealing the causation—whether that be the history of refractive or cataract surgery, ocular surface disease, infection, systemic disorders, systemic pain syndromes, etc. Clinicians often dismiss these patients due to the lack of clinical findings.[2]

Initial examination of an ocular neuropathic pain patient resembles a dry eye workup. The ocular surface should be assessed with vital stains, tear production measured via Schirmer test, and tear quality evaluated with tear break up time, tear osmolarity, and/or tear proteomics.[6]

The ocular surface will appear healthy, unlike cases of dry eye which may present with surface staining, abnormal tear osmolarity, etc.[1] When the patient has subjective complaints of corneal pain without objective findings, it should raise suspicion of ocular neuropathic pain. Examiners must keep in mind that it is also possible for dry eye to be comorbid with ocular neuropathic pain and it can be difficult to differentiate these two diagnoses when they present together.

Distinguishing between central or peripheral pain origins for ocular neuropathic pain can be helpful when determining treatments. A proparacaine challenge test can be used to make this determination.[1][6] If patients experience either complete or partial relief with topical 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride they likely have peripheral or mixed combined forms, respectively. If no relief or there is a worsening of symptoms, then the patient has central sensitization of pain, which can be very challenging to treat.[1][6]

Treatment / Management

Severe pain sensation and light sensitivity prevent those afflicted with ocular neuropathic pain from performing activities of daily living and is associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression—even suicidal thoughts in extreme cases.[6]

Treatment strategies encompass several approaches[1][6][3]:

Ocular surface treatment:

- Copious lubrication with artificial tears decreases the hyperosmolarity of tears and halts over-stimulation of corneal nociceptors. Preservative-free tear supplements are preferred if frequent instillation is needed.

- Topical and/or systemic antibiotics along with dietary supplements (omega3 fatty acids) to treat evaporative dry eye and blepharitis

- Bandage contact lenses

- Scleral lenses provide a cushion of fluid over the entire cornea, while some patients experience immediate relief, for some patients, the lenses can trigger pain due to severe hyperalgesia[1] PROSE contact lens (prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem) is custom made rigid gas permeable lens with liquid reservoir and may be helpful in post-LASIK neuralgia.

- Compounded lacosamide 0.1% may combine with preservative-free saline inside the bowl of a scleral lens

Anti-inflammatory[6][11][1]:

- Soft steroids such as fluorometholone or loteprednol to dampen surface inflammation

- Topical or oral NSAID agents

- Topical immunomodulators such as cyclosporine 0.5% or lifitegrast 5% is also an option, but their therapeutic effects are not immediate

- Tacrolimus 0.03% eye drops have been shown to improve tear stability and have an anti-inflammatory effect

- Topical or oral antibiotics such as doxycycline or azithromycin are useful adjunct therapy when meibomian gland dysfunction is present

- Amniotic membranes provide anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and neurotrophic effects; since not all patients can tolerate the polycarbonate ring of self-retained tissues such as PROKERA, the corneal amniotic membranes can be placed underneath a bandage contact lens

Neuroregeneration:

- Autologous serum tears (20%)- Serum contains various growth factors which play a crucial role in neuroregeneration and healing - these factors include nerve growth factor, transforming growth factor beta, insulin-like growth factor 1, epidermal growth factor, fibronectin, and substance P

Others[12][13][14]:

- Systemic analgesics, tricyclic antidepressants (10 to 15 mg at bedtime), and antipsychotics to treat associated non-ocular pain

- Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine (200 mg/day), gabapentin (300 to 900 mg/day) or pregabalin (150 mg/day), which are also used to treat trigeminal neuralgia

- Low dose naltrexone (1.5 mg at bedtime), an opioid antagonist used off-label

- Opioid agonists such as tramadol (50 mg/day) may provide acute relief but require caution due to the potential for dependence

- Vitamin B has proven effective in herpes, diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathic pain

- Also assists with re-innervation and re-epithelization of the corneal surface - specifically, B12 increases serotonin levels and inhibits nociceptive neuronal activity

Alternative therapies[1][6][1]:

- Acupuncture treatment semi-weekly

- Electrical neurostimulation to treat chronic intractable pain with central sensitization

- Invasive neuromodulation therapies such as deep brain stimulation and Intrathecal analgesic infusions may provide relief for severe, intractable cases of neuropathic pain

Differential Diagnosis

As previously noted, ocular neuropathic pain is a diagnosis of exclusion. The following are essential to rule out[1]:

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Oculofacial pain

- Referred pain

- Ocular surface disease

- Sinus dysfunction

- Ocular medication toxicity

- Contact lens-related problems

- Corneal disorder (abrasion, erosion, infiltrate, ulcer, etc.)

- Chemical injury

- Trauma

- Uveitis

- Post-herpetic neuralgia

Take, for example, ocular surface disease. The mechanism is as follows: reduced tear secretion leads to inflammation. Inflammation causes sensitization of nociceptive nerve endings, which leads to feelings of dryness and pain. In the long term, inflammation and nerve injury alter gene expression within the trigeminal ganglion, propagating ocular dysesthesias and neuropathic pain.[10] It is easy to see how this particular differential diagnosis is often a misdiagnosis of ocular neuropathic pain.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with ocular neuropathic pain dramatically varies. Patients often have chronic symptoms requiring a multimodal treatment approach.[2][6] Early interventions yield better outcomes.

Complications

For reasons other than the obvious, treatment and management of chronic pain is an arduous task. Patients with chronic pain become increasingly anxious about it, and anxiety correlates with increased susceptibility to pain–a vicious cycle.[3] Chronic pain is not only psychologically taxing but physically as well. Studies have found comorbidity with many other conditions such as chronic fatigue, joint pain, and depression.[15]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventative screenings for certain risk factors, including autoimmune diseases and systemic pain conditions, should be considered before planning refractive surgeries such as LASIK. This approach may reduce the risk of subsequent development of ocular neuropathic pain.[3] Additionally, since patients suffering from more severe cases of ocular neuropathic pain also more frequently report overlapping psychiatric disease, screening for pre-existing personality disorders which could predispose a patient to depression and suicidal thoughts are equally important.[16] Healthy-minded individuals are more equipped to cope with chronic pain for longer while they seek treatment and are less likely to resort to self-harm.

Patients with ocular surface disease indicated higher pain responses at non-ocular sites such as the forearm compared to those without the condition, which would indicate that patients with the ocular surface disease have a lower systemic pain threshold, as is consistent with central sensitization in dry eye patients.[5]

To reiterate, an important first step in treating ocular neuropathic pain is to communicate the belief that the condition is real.[2] The second is to actively screen for it.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Dry eye patients who fail to respond to dry eye treatments and have persistent symptoms without objective findings warrant further investigation

- An important first step in treating ocular neuropathic pain is to communicate the belief that the disease is real, as there is often a psychological component associated with this chronic pain

- Ocular neuropathic pain is a diagnosis of exclusion; a thorough case history is important along with an examination of ocular health

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Given the challenges in both diagnosis and treatment of ocular neuropathic pain, the best approach to this condition is with an interprofessional team consisting of physicians, specialists (including neurology, psychiatry, rheumatology, ophthalmology and optometry), specialty-trained nursing, and when appropriate, pharmacists and psychological personnel, all communicating across disciplines to direct the case towards optimal clinical results. [Level V]