Continuing Education Activity

Renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), which originate within the renal cortex, are responsible for 80% to 85% of all primary renal neoplasms. Transitional cell carcinomas, which originate in the renal pelvis, comprise approximately 8%. Other parenchymal epithelial tumors, such as oncocytomas, collecting duct tumors, angiomyolipomas, and renal sarcomas, occur infrequently. This activity reviews the causes, pathophysiology, presentation and diagnosis of renal cell cancers and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of renal cell cancer.

- Explain the workup of a patient with renal cancer.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for renal cell cancer

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with renal cell cancer.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinomas (RCCs), which originate within the renal cortex, are responsible for 80% to 85% of all primary renal neoplasms. Transitional cell carcinomas, which originate in the renal pelvis, comprise approximately 8%. Other parenchymal epithelial tumors, such as oncocytomas, collecting duct tumors, angiomyolipomas, and renal sarcomas, occur infrequently. In children, nephroblastoma and Wilms tumor are common. Medullary renal carcinoma is a rare but aggressive form of renal cell cancer that seen in sickle cell disease. Other less common subtypes are clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe malignancies.[1][2][3]

Etiology

The exact cause of RCC is unknown. The following factors increase a person's risk for renal cancer: older age, obesity, hypertension, chronic renal failure, dialysis treatment, polycystic kidney disease, African American race, sickle cell disease, and renal stones.[4][5]

The following hereditary diseases increase the risk of RCC: tuberous sclerosis, Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome, hereditary papillary renal carcinoma, and hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC).

Many studies have suggested that workplace exposure to certain substances increases the risk of RCC. Some of these substances are cadmium, herbicides, asbestos, and trichloroethylene.

Epidemiology

RCC is the most common type of kidney cancer in adults. It occurs most often in men ages 50 to 70.

Globally, the incidence of RCC varies, with the highest rates observed in the Czech Republic and North America. In the United States, there are approximately 63,000 new cases and almost 14,000 deaths each year.

In the United States, incidence rates of RCC have been on the rise through the mid-2000s. Most of the increases since the 1980s occurred in early-stage tumors.[6]

Pathophysiology

The proximal renal tubular epithelium is the kidney tissue from which RCC arises. The two forms are sporadic: nonhereditary and hereditary. The structural alterations of both forms occur on the short arm of chromosome 3 (3p).

Families at high risk for developing renal cancer were studied, which led to the cloning of genes. The genes whose alteration resulted in RCC formation were tumor suppressors (VHL, TSC) or oncogenes (MET).

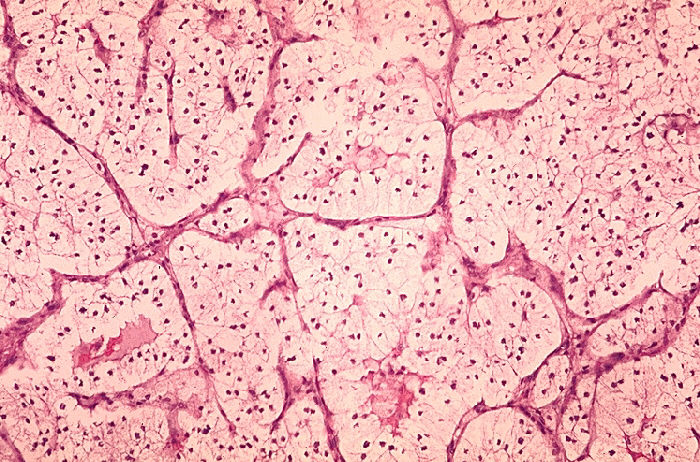

Histopathology

Subtypes of renal cell cancer include:

- Clear cell- most common and contains a cytoplasm rich in glycogen and lipids. This subtype is likely to be associated with 3p deletion.

- Chromophilic masses are often bilateral and be associated with trisomy 7/17

- Chromophobic lesions have large polygonal cells but rarely have 3p deletion

- Oncocytoma lesions have predominance of eosinophilic cells but rarely exhibit any chromosomal defects. These lesions are least likely to spread

- Collecting duct are very aggressive, occur in young people and often present with advanced disease

History and Physical

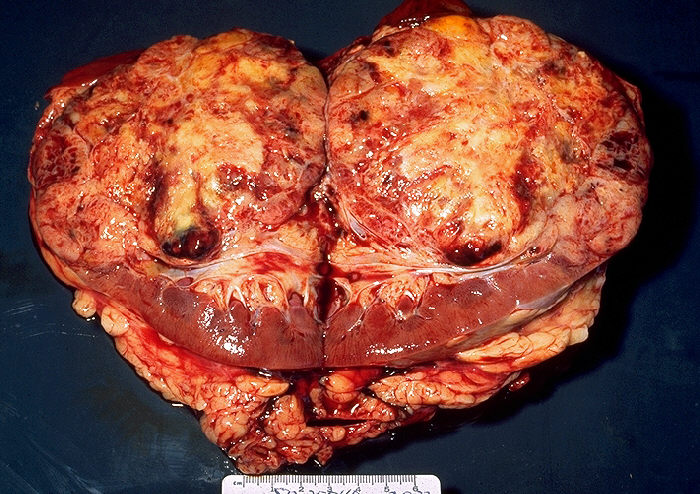

In the early stages, when the mass is small (less than 3 centimeters), renal cell cancer is typically asymptomatic. Approximately 25% of patients are asymptomatic, and the solid renal mass is an incidental finding during a routine radiological study.

As the mass grows, symptoms may include hematuria, back pain, flank mass, fatigue, weight loss, anemia, fever, and/or high serum calcium level.

The classic clinical triad of flank pain, hematuria, and flank mass is not common, presenting in only 10% of patients. When this classic triad is present, it usually indicates advanced disease.

Evaluation

A urine test may show hematuria. Urine analysis may detect cancer cells in the urine. A blood test may show anemia or high serum calcium levels.[7][8]

If RCC is suspected, renal and bladder ultrasound is usually the first radiographic test. If the renal ultrasound shows a solid mass or a complex cyst with septations or nodules, the next test should be a dedicated CT scan of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder before and after IV contrast with delayed imaging of the entire abdomen and pelvis.

If the renal ultrasound is negative, but the patient has unexplained hematuria, a CT scan before and after IV contrast should be the next test as small solid renal masses can be easily missed on ultrasound and small renal stones also can be missed on ultrasound.

On CT scan, RCC will typically demonstrate significant enhancement; usually, greater than 20 Hounsfield units (HU), more after contrast. Typically, postcontrast HU of renal cancer measure about 141 HU. The subtypes papillary cell and clear cell may enhance less than RCC.

CT scan is used to stage RCC. CT scan will detect lymphadenopathy and invasion to the renal vein or inferior vena cava or invasion to adjacent organs. CT scan can detect metastatic disease to the bones of the abdomen and pelvis only. Whole body bone scan is the test of choice to detect bone metastases. Chest CT scan also should be obtained, as RCC presents with lung metastases in about 10% to 20%. The use of PET-CT is controversial but is helpful for distant metastases.

Abdominal MRI is just as good as CT scan for diagnosing and staging RCC but is more subject to limitations such as respiratory motion artifact because the images take longer to acquire.

Treatment / Management

Treatment depends on the stage of the tumor. See staging."

- For stage I renal cell cancer measuring less than 7 centimeters and confined to the kidney, nephrectomy or partial nephrectomy is the treatment of choice and is usually curative. Radiofrequency ablation or cryotherapy is an option in patients with bilateral tumors and small cortical tumors. Imaging surveillance is an option in elderly patients with a short life expectancy who are not good surgical candidates, as many renal cell cancers are slow growing.

- For stage II renal cell cancer, laparoscopic radical nephrectomy is the treatment of choice.

- For stage III renal cell cancer, open radical nephrectomy is the standard of care. Adrenalectomy or extensive lymph node dissection is only recommended when abdominal CT shows evidence of adrenal or lymph node invasion.

- Stage IV renal cell cancer is not curable. Treatment is palliative. Treatment may include tumor embolization, external-beam radiation therapy, and nephrectomy, but these treatments are not aimed at cure, rather prolonged survival and palliation. Immunotherapy and chemotherapy can prolong survival. Drugs that may be used to reduce the risk of complications from bone metastases include bisphosphonates and Xgeva.[9][10]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of other solid renal tumors includes the following: renal oncocytoma, lipid-poor renal angiomyolipoma, renal metastases, renal lymphoma, solitary fibrous tumor (very rare), and multilocular cystic nephroma.

Other renal abnormalities that can mimic RCC include the following: a prominent column of Bertin, renal abscess, renal infarct, and complex renal cyst.

The finding of a prominent column of Bertin is typically a questionable ultrasound finding which requires cross-sectional imaging CT scan or MRI to confirm.

The finding of renal access typically has other clinical findings to support such as pyelonephritis, high white blood cell (WBC) count, fever, and chills.

The finding of renal infarct is usually associated with vascular abnormalities such as renal vein thrombosis or trauma related.

To differentiate a complex renal cyst from renal cell cancer, radiologists use the Bosniak classification.

Staging

Below is the Robson staging for RCC; although it has largely been replaced by the TNM staging which is much more complicated.

Robson staging:

- Stage I: limited to kidney

- Stage II: involvement of perinephric fat but remains limited to Gerota's fascia

- Stage III

- IIIa: renal vein involvement

- IIIb: nodal involvement

- IIIc: both IIIa and IIIb

- Stage IV

- IVa: direct invasion of adjacent organs/structures

- IVb: distant metastases

TNM staging (seventh edition)

- T1

- T1a: limited to kidney, greater than 4 cm

- T1b: limited to kidney, greater than 4 cm but less than 7 cm

- T2: limited to kidney, greater than 7 cm

- T2a: limited to kidney, greater than 7 cm but not more than 10 cm

- T2b: limited to kidney, greater than 10 cm

- T3: tumor/tumor thrombus extension into major veins or perinephric tissues but not into ipsilateral adrenal gland or beyond the Gerota fascia

- T3a: spread to renal vein

- T3b: spread to infra-diaphragmatic IVC

- T3c: spread to supradiaphragmatic IVC or invades the wall of the IVC

- T4: involves ipsilateral adrenal gland or invades beyond Gerota's fascia

- N0: no nodal involvement

- N1: metastatic involvement of regional lymph node/sM

- M0: no distant metastases

- M1: distant metastasesStage groupings

- Stage I: T1 N0 M0

- Stage II: T2 N0 M0

- Stage III: T3 or N1 with M0

- Stage IV: T4 or M1

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on stage on histology of the cell type.

- Stage 1 has a 90% 5-year survival rate.

- Stage 2 has a 50% 5-year survival rate.

- Stage 3 gas a 30 % 5-year survival rate.

- Sagte 4 has a 5% 5-year survival rate.

Papillary RCC has the best 5-year survival rate, 90%. Clear cell cancer subtype has second-best 5-year survival, 70%.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Evidence-based approach to renal cell cancer

Renal cell cancer is relatively common in the US and often presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms. The malignancy is ideally managed with an interprofessional team that includes a urologist, nephrologist, oncologist, and a geneticist. Over the past two decades, the mortality rates from this malignancy have dropped because of earlier detection and treatment. five-year survival for stage 1 cancer is greater than 90% and 79% for stage 2 renal cancer. For those with lymph node involvement, the survival drops to less than 40% over five years. Factors associated with improved survival include obesity, good performance status, complete excision of the primary and a long disease-free interval from the time of surgery to the presence of metastases. Patients with a family history should be educated about the need for other members of the family to undergo screening. Patients at high risk for renal cell cancer should also be educated about the signs and symptoms; as earlier the cancer is managed, the better the prognosis.[11][12] (Level V)