Continuing Education Activity

Pneumonia is a lower respiratory tract infection, specifically involving the pulmonary parenchyma. Viruses, fungi and bacteria can cause pneumonia. The severity of pneumonia can range from mild to life-threatening, with uncomplicated disease resolving with outpatient antibiotics and complicated cases progressing to septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death. It affects all age groups, accounts for over 2 million emergency visits annually, and is a leading cause of mortality in both adults and children. Atypical micro-organisms are known to cause a disproportionate disease burden in children and adolescents. This activity reviews the causes, presentation and diagnosis of atypical bacterial pneumonia and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of these patients.

Objectives:

- Identify the bacteria known to cause atypical pneumonia.

- Review the presentation of a patient with atypical bacterial pneumonia.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for atypical bacterial pneumonia

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with atypical pneumonia.

Introduction

Pneumonia is a lower respiratory tract infection, specifically involving the pulmonary parenchyma. Viruses, fungi, and bacteria can cause pneumonia. The severity of pneumonia can range from mild to life-threatening, with uncomplicated disease resolving with outpatient antibiotics and complicated cases progressing to septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and death.[1] It affects all age groups, accounts for over 2 million emergency visits annually, and is a leading cause of mortality in both adults and children. Atypical micro-organisms are known to cause a disproportionate disease burden in children and adolescents. Atypical organisms are difficult to culture. They present subacutely and with progressive constitutional symptoms.[2]

While streptococcus pneumonia accounts for about 70% of cases, the rest are caused by atypical organisms.

Etiology

Pneumonia is acquired when a sufficient volume of a pathogenic organism bypasses the body’s cough and laryngeal reflexes and makes its way into the parenchyma. This can occur from being exposed to large volumes of pathogens in inspired air, increasingly virulent pathogen exposure, aspiration or impaired host defenses. Given the different environments in which one may acquire pneumonia, the diagnosis is often broadly classified into community-acquired or hospital-acquired.[1] It may be further classified as viral, bacterial, or atypical bacteria based on the suspected pathogen requiring treatment. Atypical pneumonia is acquired from various sources. There are a vast number of pathogens that are considered atypical, but the most commonly identified are mycoplasma pneumoniae which are associated with close living conditions like at school and military barracks, legionella from stagnant water sources, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Coxiella brunette, and Francisella tularensis from various mammalian sources.[3]

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is responsible for the vast majority of atypical respiratory infections. However, only about 10% of patients who acquire mycoplasma will develop pneumonia. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection tends to be more common with advancing age, especially the elderly. The infection can occur all year round and outbreaks in small communities is common (Eg schools, homes). The organism is transmitted from person to person and the infection usually spreads slowly. Once the organism is acquired, the symptoms may take 4-20 days to appear and include malaise, cough, myalgia and sore throat. The cough is often dry and worse at night. Most cases of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection are mild and resolve on their own. Mycoplasma can also cause a variety of extrapulmonary symptoms like erythema nodosum, urticaria, erythema multiforme, aseptic meningitis, Guillain Barre syndrome, and cerebral ataxia. Individuals with preexisting lung disease may develop empyema, pneumothorax or even respiratory distress syndrome.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is also a common cause of infection of the lung. The organism is acquired after inhalation of contaminated aerosolized droplets. However, the incubation period is long and symptoms are usually mild. chlamydia pneumoniae infection is most common in elderly people. The infection presents with a sore throat, cough and a headache that can last for many weeks or months. The chest x-ray may show a mild infiltrative process. Death is rare but can occur in patients with comorbidities.

Legionella pneumoniae is the most pathogenic of the atypical bacteria that cause lung infection. Several serotypes exist and infection tends to occur in close quarters. Spread from other humans is rare; most cases are due to inhalation of the pathogen from water systems like humidors, whirlpools, respiratory therapy equipment, water faucets, and air conditioners. Places for water stagnates allows for the organism to proliferate. Individuals at risk for legionella may have diabetes, malignancy, renal or liver failure and may have had recent plumbing done in the home. Once acquired, the patient may present with altered mental status, cough, fever, and respiratory distress. At least 20-40% of patients develop diarrhea. Blood work may reveal leukocytosis and the sputum gram stain may show accumulation of inflammatory cells without any organism. Of the atypical organisms, legionella has a severe course and the illness can quickly become severe if not treated promptly. While extra pulmonary symtoms are rare, many patients develop severe respiratory distress often requiring mechanical ventilation.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that 7% to 20% of community-acquired pneumonia is secondary to atypical bacterial microorganisms. Given their intra-cellular nature, they are not visible on gram stain and are difficult to culture[4]; therefore, the true number of cases is unknown, but given similar treatments, specific etiology is often unnecessary. There is a preference for younger individuals, with age being the only reliable predictor in adults.

Pathophysiology

When the inoculating organisms overwhelm the host defenses, it causes a proliferation of the infectious agent. The pathogen replicating initiates the host immune response, and further inflammation, alveolar irritation, and impairment occur. This leads to the following signs and symptoms; cough, sputum production, dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxia.[1] Atypical infections result in less lobar consolidation. Therefore, patients do not usually appear toxic; hence the common term “walking pneumonia.”

Atypical organisms are an inclusive term for organisms difficult to culture and not apparent on gram stain. Given their intracellular nature, they are difficult to isolate and often challenging to treat because antibiotics must be able to penetrate intracellularly to reach their intended target. They are also grouped based on their subacute presentation and similar constitutional symptoms.

History and Physical

Patients often present with prolonged constitutional symptoms. Although not found to be predictive, it is traditionally taught that patients with atypical infections will present gradually and have a viral prodrome including a sore throat, headache, nonproductive cough, and low-grade fevers.[2] They rarely have an obvious area of consolidation on auscultation/imaging compared to pneumococcal pneumonia. Additionally, extra-cardiopulmonary symptoms are often seen; for example, mycoplasma infections are loosely associated with rashes, and bullous myringitis and Legionella is classically associated with gastrointestinal ailments and electrolyte abnormalities.

Evaluation

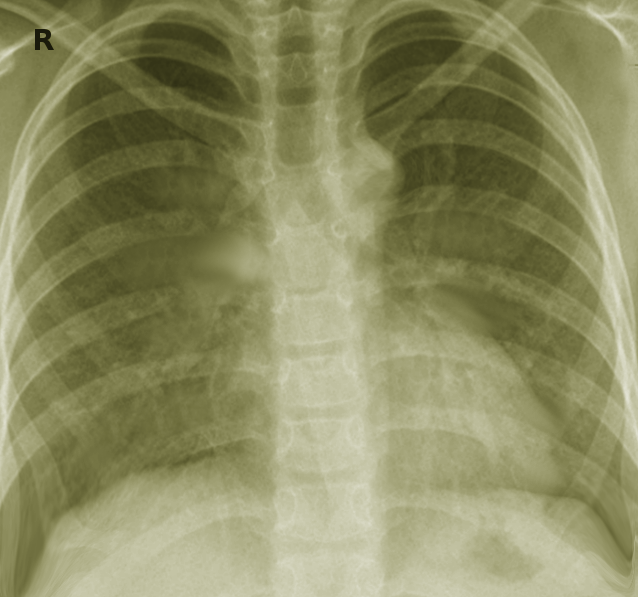

In a nontoxic-appearing patient, especially in the outpatient setting, a high clinical suspicion is all that is needed to pursue empiric treatment. In ill-appearing individuals or patients in whom the diagnosis is uncertain, a chest x-ray is the diagnostic gold standard. Lab work often complements and further serves to help risk-stratify individuals and direct treatment. Decision-making is only supplemented by lab studies. Some providers may check a complete blood count to test for leukocytosis and a left-shift, or complete a pro-calcitonin test to help differentiate viral versus bacterial etiology. [5][6][7]Patients who are admitted to the hospital have urinary antigen tests and viral PCRs, allowing for detection of legionella, chlamydia, and mycoplasma. When patients appear toxic, it is also important to obtain blood cultures and sputum cultures, if possible,[2] to help with antimicrobial stewardship and the de-escalation of antibiotics.

Classic imaging findings in atypical pneumonia include patchy infiltrates, sometimes bilateral in distribution, and interstitial patterns. They are less commonly associated with lobar consolidations and complicated parenchymal findings such as empyema and ARDS.

Treatment / Management

Atypical organisms such as M. pneumoniae, which is the most common, lack cell walls; therefore, beta-lactam antibiotics are not recommended. One does not have to perform blood cultures before initiating treatment. However, sputum should be obtained for gram stain and culture. In hospitalized patients, antibiotics should be started within 4 hours.

First-line treatment is the macrolide family of antibiotics, although resistance is emerging. Azithromycin is the most common and is available in intravenous and oral formulations; the short treatment course of just 5 days increases patient compliance. Alternate outpatient antibiotics include fluoroquinolone and tetracycline. These are frequently utilized in older or more toxic-appearing individuals when more pyogenic organisms are also considered. In patients requiring hospital admission for presumed community-acquired pneumonia, a broadened approach is frequently utilized, and a beta-lactam such as ceftriaxone is added to azithromycin.[1]

Clinician tools such as the CURB 65 score and the pneumonia severity index are frequently utilized to determine if outpatient or inpatient medical treatment is most appropriate. [5][8]Well-appearing individuals in whom an atypical organism is suspected can be managed with outpatient antibiotics and symptomatic care.

Treatment failures are not uncommon due to antibiotic resistance, poor compliance and inability to tolerate oral medications. In addition, some patients may have obstructing lung lesions or an incorrect diagnosis.

Close to 50-60% of patients may have a parapneumonic effusion on the chest x-ray. If this fluid does not resolve, empyema is common. Aspiration and drainage of the fluid are highly recommended if the pH is less than 7.2.

In children less than 5, atypical pathogens are not common but if suspected the treatment is amoxicillin for 7-14 days. Macrolides are recommended for children more than 5 years old. Children who develop atypical pneumonia are more likely to need hospitalization and often require parenteral therapy as well as oxygen supplementation.

Elderly patients with atypical pneumonia often have altered mental signs and another comorbidity which also increase the risk for aspiration. These individuals should also be covered for anaerobes.

Criteria for Admission

- Respiration rate more than 30 bpm

- Oxygen saturation less than 90% on room air

- Hypotension

- Severe lung disease, COPD, emphysema,

- Heart failure, diabetes

- Altered mental status

- Delirium

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for pneumonia typically spans cardiac, respiratory, and musculoskeletal systems. From the cardiac system, pericarditis and myocarditis can present in the setting of viral symptoms and should be considered. In the respiratory system, one must differentiate between upper and lower respiratory tree. The upper respiratory system includes pharyngitis, sinusitis and more emergent conditions such as epiglottitis and retropharyngeal abscess. For the lower respiratory tree, a chest x-ray will differentiate bronchitis/bronchiolitis versus pneumonia. It further complicates the diagnosis when an abnormal infiltrate is found on chest x-ray; in these cases, one must differentiate between atypical/viral/bacterial pneumonia, polymicrobial aspiration, and sterile chemical pneumonitis. Other noninfectious respiratory mimickers include asthma and COPD.[2] Lastly, it is important to consider musculoskeletal complaints such as costochondritis and rib dysfunction; however, they frequently lack constitutional symptoms.

Prognosis

The vast majority of patients in whom an atypical infection is suspected can be managed successfully as an outpatient. There is usually a complete resolution of symptoms and a low morbidity and mortality. Treatment is often uneventful in the absence of significant comorbid conditions, vital sign abnormalities, and a toxic appearance. As with all clinical disease, not every case follows the expected course. Close follow-up and compliance are necessary to monitor for disease progression.

Deterrence and Patient Education

- The public should be encouraged to get vaccinated with the annual flu.

- Elderly individuals should also get the pneumococcal vaccine

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of atypical pneumonia is often difficult because laboratory results are not always immediately available, hence clinical acumen is necessary. The infection is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an emergency department physician, infectious disease consultant, nurse practitioner, internist, radiologist, and a pharmacist. Because diagnosis is often delayed, one should never delay treatment if atypical pneumonia is suspected. The pharmacist should educate the patient on medication compliance and the importance to have the annual flu vaccine. Nurses should closely monitor patients for respiratory distress, nutrition, and mental status changes. If the patients are managed as outpatients, an infectious disease nurse should follow the patients in a clinic to ensure that recovery is occurring.

The majority of patients are managed as outpatients without sequelae. However, some atypical pneumonia may not follow the usual course and may result in severe symptoms, which require admission. [9][10]To avoid the morbidity and mortality, it is important to follow these patients until full resolution of symptoms is obtained. [11] Close communication between the interprofessional team is vital to obtain improved outcomes.