Introduction

The two principal venous tributaries in the pelvis are the internal and external iliac veins, while the gastric veins dominate the abdomen. The union of the internal and external iliac veins creates the common iliac vein, while the inferior epigastric vein drains into the external iliac vein and anastomoses from the superior epigastric vein. The primary function of these veins is to drain deoxygenated blood and return this blood to the heart. Lymphatic nodes are dispersed throughout the pelvic vasculature. The internal, external, and common iliac nodes drain the pelvis and its contents, while the inferior epigastric vein empties into the external iliac vein. For example, the contents of the pelvic viscera are drained by the internal iliac nodes while being surrounded by branches of the internal iliac vessels. Furthermore, complex pelvic surgeries are subject to further complications by the various anatomical variants of the iliac veins. Treatment outcomes can improve by being able to recognize the anatomical variants correctly.

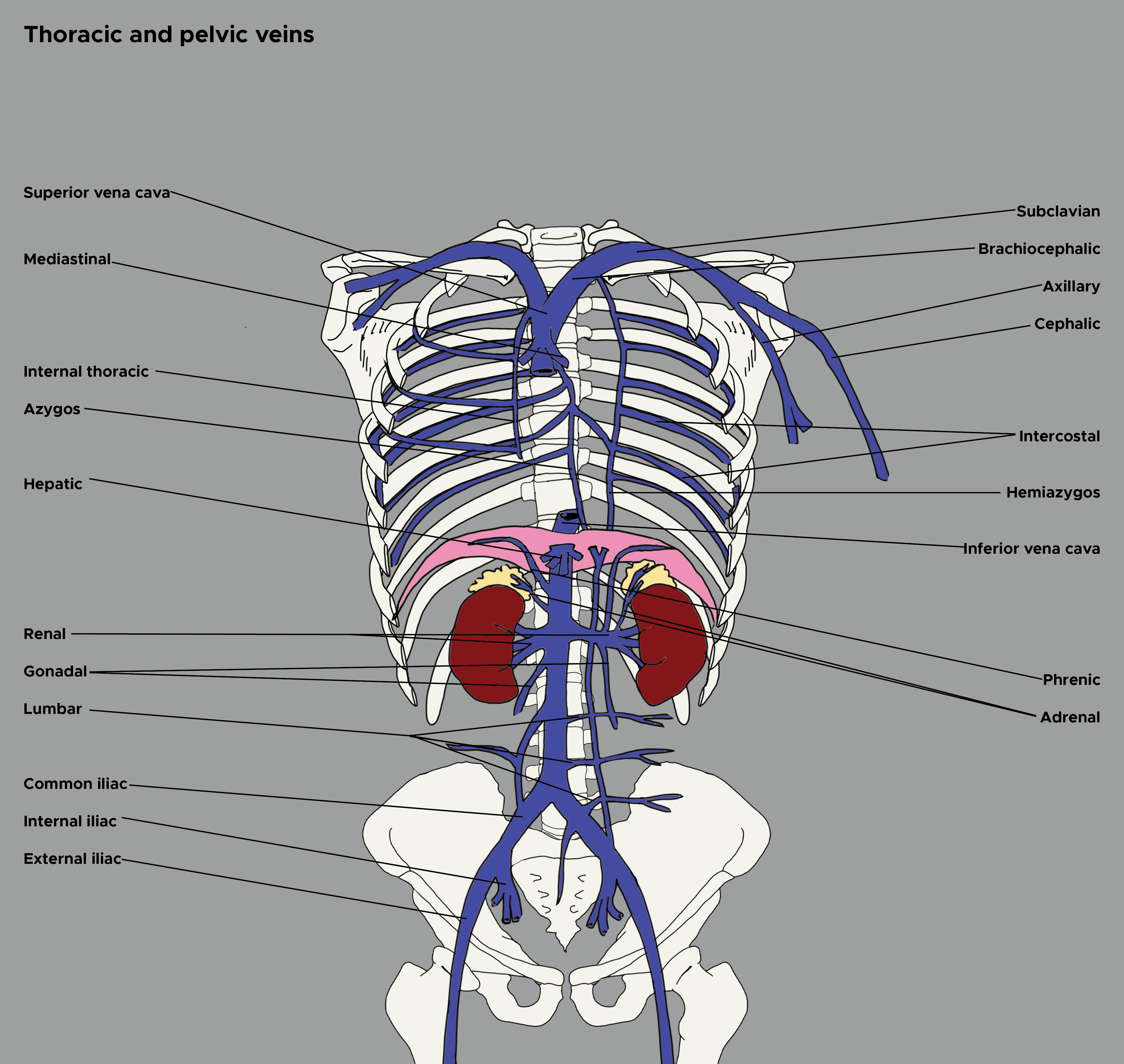

Structure and Function

The network of veins in the lower extremities, abdomen, and pelvis is composed of various superficial and deep veins. Perforating veins join together the superficial and deep veins by traveling across the muscular fascia. Superficial veins are located between the skin and muscular fascia, while deep veins accompany arteries and drain muscles. Intima, media, and adventitia compose the vein wall. The intima is anti-thrombogenic due to the in situ production of prostaglandin I2, cofactors of antithrombin, and tissue-type plasminogen activator. Three smooth muscle layers, combined with collagen and elastin, make up the media. While the adventitia is the thickest and outermost layer of the vein wall.[1]

The primary function of the pelvic veins and gastric veins is to drain deoxygenated blood and return it to the heart. Forming in the abdomen at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebrae, the common iliac vein forms through the unification of the external iliac vein and the internal iliac vein. Each set of external and internal iliac veins on the right and left sides of the body form an associated left or right common iliac vein. The left common iliac vein and right common iliac vein join to form the inferior vena cava (IVC).[1] Furthermore, the gastric veins play a significant role in returning deoxygenated blood into the systemic venous circulation. A major pathway, the left gastric vein, brings blood flow into the esophageal varices via the upper stomach.[2] This vein is also known as the gastric coronary vein and serves an essential role in the venous system of the stomach.[3] Additional major abdominal veins are present near the abdominal wall. The venous drainage of the superficial anterolateral abdominal wall involves an elaborate subcutaneous venous plexus. This plexus drains superiorly and medially to the internal thoracic vein. It drains superiorly and laterally to the lateral thoracic vein. Further, the plexus drains inferiorly to the superficial epigastric vein and the inferior epigastric vein, which are tributaries of the femoral vein and external iliac vein, respectively.[2]

As for location, the inferior epigastric vein drains into the external iliac vein and anastomoses from the superior epigastric vein. The left gastric vein originates from the portal vein or splenic vein, and these veins run along the lesser curvature of the stomach from the esophagogastric junction.[4]

For pelvic veins, the left and right common iliac veins have differing pathways. The right common iliac vein moves in a straight course to form the IVC, while the left common iliac vein must initially join the right common iliac vein at the confluence with the IVC. Therefore, the left common iliac vein’s pathway is not as linear.[1] The left common iliac vein is also longer than the right and receives drainage from the median sacral vein. The iliolumbar and lateral sacral veins drain into both common iliac veins.[5] Frequently containing 1-2 valves, the external iliac vein receives from the following: the inferior epigastric vein, the deep circumflex iliac vein, and other pelvic veins. The inferior epigastric vein joins the external iliac vein superior to the inguinal ligament. The common femoral vein transitions to form the external iliac vein, which occurs at the level of the inguinal ligament. The external iliac vein receives the deep circumflex iliac vein and inferior epigastric vein via the same venous tributaries as the external iliac artery.[1] The internal iliac veins drain parietal and visceral plexuses (two independent networks that form the intrapelvic venous system) through the use of valveless interconnected pathways. It also functions as the main venous drainage system of small pelvic veins. The internal iliac vein also receives venous drainage from the middle rectal veins, pudendal veins, obturator, and inferior and superior vesical veins.[6]

Gonadal veins are one of the visceral veins which branch from the internal iliac vein. The left gonadal veins drain into the left renal vein, while the right gonadal vein joins the IVC. These veins can help prevent reflux.[1]

Embryology

Cardinal veins provide the majority of venous drainage into the sinus venosus during embryogenesis. The anterior cardinal veins drain cranial portions of the embryo, while the posterior cardinal veins drain the caudal portion. These posterior cardinal veins regress, except for the iliac anastomosis, supracardinal, and subcardinal sections.[5] The supracardinal piece gives rise to the inferior vena cava (from which the gastric veins derive) between the sixth and eighth gestational weeks, while the iliac anastomosis gives rise to the common, external, and internal iliac veins.[5][2] This development is critical because any malformations during this growth can result in agenesis of the common iliac vein.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The skin in the inguinal region drains via the superficial epigastric vein, a tributary of the femoral vein. Branches of the superior and inferior epigastric veins accompany cutaneous nerves and carry deoxygenated blood from the superficial abdominal wall. The inferior epigastric vein then drains into the external iliac vein above the inguinal ligament.[2]

For pelvic tributaries, the internal, external, and common iliac lymph nodes drain the pelvis and its contents. There are generally two pelvic lymphatic pathways. The first is an upper paracervical that courses along the uterine artery with draining external iliac lymph nodes. The second is a lower paracervical pathway that runs along the uterine vein to the hypogastric area.[7][8]

The internal iliac nodes, surrounded by the branches of the internal iliac vessels, drain the contents of the pelvic viscera. The external iliac nodes arrange in various medial, anterior, and lateral clusters. The medial subgroup of nodes is the primary drainage channel and receives lymph from inguinal nodes and adductor regions. The clitoris or glans penis, membranous urethra, prostate, uterine cervix, and upper vagina are drained by these nodes as well. The internal and external iliac nodes both empty into the common iliac nodes.

Nerves

Many nerves innervate the abdomen and pelvic area. The visceral peritoneum is supplied by autonomic nerves, both sympathetic and parasympathetic, while the spinal nerves innervate the parietal peritoneum. The left and right vagus nerve, celiac plexus, and gastric nerves innervate the abdomen.[9]

The lumbosacral trunk, sacral plexus, and coccygeal plexus pass through the pelvic cavity, while the sacral ventral rami innervate the pelvis viscerally and muscularly. Also, parasympathetic pelvic splanchnic fibers and sympathetic sacral splanchnic fibers innervate the viscera of the pelvis, along with the superior hypogastric plexus and sacral plexus. A parietal layer of the pelvic fascia line the pelvic cavity and covers the piriformis muscle and the sacral plexus.[8]

Muscles

Active forces from compartmental muscle pumps from the pedal, calf, and thigh account for the majority of deep venous return from the lower extremities. Intracompartmental pressure increases with muscle contraction, which facilitates flow across the unidirectional valves in the veins. The calf muscle has the largest capacitance, and as a pump, it creates the highest pressures. According to one study, the calf muscle has an ejection fraction of about 65% compared to 15% from the thigh pump. Similarly, the facilitation of the blood flow in the veins of the feet occurs via intra-pedal muscular contractions.[1]

Physiologic Variants

Anatomists have found variants in iliac veins. Right and left common iliac veins usually form by the joining of an external and internal iliac vein. The union of these veins forms a single inferior vena cava. There have been variations relative to the forming of the inferior vena cava by other tributaries.[10]

The internal iliac vein can lie either medially or laterally. Normal iliac vein anatomy is defined as follows: a bilateral common iliac vein joined to form a right-sided inferior vena cava and a bilateral common iliac vein formed by internal and ipsilateral external iliac vein at a low position. About 79.1% have normal internal iliac vein anatomy, assuming they meet the criterion above.[11]

Similar to the internal iliac vein, the left gastric vein yields many anatomical variations as well. Further research is needed to determine detailed anatomical findings of the left gastric vein branches and their relationship to the lower esophagus.[3]

Surgical Considerations

Due to the location and complex variation, the iliac veins provide a significant risk for hemorrhage complications. Isolation and vascular exposure of the internal iliac vein and external iliac vein are crucial procedures to control possible hemorrhage. To de-vascularize the pelvis during exenterations and ensure safe dissection of the lateral sacral margin during sacrectomies, surgeons often ligate the internal iliac vein and its tributaries. The internal iliac vein has several classification patterns, with 7 to 11 subtypes. As a result, the internal iliac vein remains significantly variable, and surgeons must take this anatomical consideration when performing pelvic surgeries.[12] Similarly, the left gastric vein is also important in laparoscopic surgeries. Due to its tributaries and anatomical variants, a detailed understanding of the left gastric vein is necessary during laparoscopies to avoid profuse bleeding.[13]

Clinical Significance

Congestion and obstruction are two themes of pathology for the venous system in the lower abdomen and pelvis. In cases of pelvic venous congestion and iliocaval obstruction, the pelvic venous pathways are of significant importance. Ovarian venous and internal iliac tributary insufficiency is usually associated with the varicosities of the vagina, vulva, and posteromedial thigh. Chronic pelvic vein congestion accompanies varicosities of the posteromedial thigh. Pelvic venous congestion and chronic left lower-extremity venous hypertension may become aggravated if extrinsic compression upon the left common iliac vein occurs.[1] Also, Iliac vein compression syndrome (IVCS) is a significant contributor to deep vein thrombosis, which is more common in pelvic veins than other veins.[14] Compression of the left common iliac vein by the fifth lumbar vertebra and the right iliac artery characterizes IVCS. This condition can lead to inflammation, scarring, local intimal injury, and, ultimately, a spectrum of venous occlusive lesions. As a result of this collateral circulation occurring over time, patients with IVC may not present any clinical symptoms early on. Though clinical symptoms are typically not present in the early stages, left lower limb deep vein thrombosis has an increased incidence with IVC. As mentioned above, many patients presenting with IVCS have no vascular-related symptoms, and young women are most commonly affected. Vascular-related symptoms include venous diseases, varicose veins, edema, swelling, ulcers, and hyperpigmentation.[14]

Pelvic congestion syndrome occurs in the lower abdomen with varicose veins, which is another chronic condition in women. Patients present with a primary complaint of chronic pain, often a constant dull ache that becomes further aggravated when standing. There is speculation that low oxygenation worsens pelvic venous congestion, which could then promote lower urinary tract dysfunction. Pelvic ischemia caused by hypertension and arteriosclerosis could flow.[15]

Moreover, the left gastric vein has significance in the management of gastric cancer. D2 lymphadenectomy remains as the standard operation for resectable non-early gastric cancer. Other important utilizations of the left gastric vein include laparoscopic surgery and treatment for extrahepatic portal hypertension by a left gastric vein portal vein shunt.[13]

Anatomical variants of the pelvic veins can also add crucial information in diagnosing possible disease states and the prevention of these states. Supine hypotensive syndrome occurs due to IVC obstruction. As a result of IVC obstruction, the body must use other venous systems to return the blood to the heart. To do so, the inferior epigastric vein and anastomosis of the external iliac vein, comprising the superficial collateral system, connect the drainage of the abdomen to the superior vena cava. Furthermore, this completely bypasses the IVC.[5]

Other Issues

Iwanaga et al. discovered a technique termed air dissection. Air is first insufflated in the IVC and then its tributaries. In a specific case, the right internal iliac vein was only visualizable using air dissection.[5]