[2]

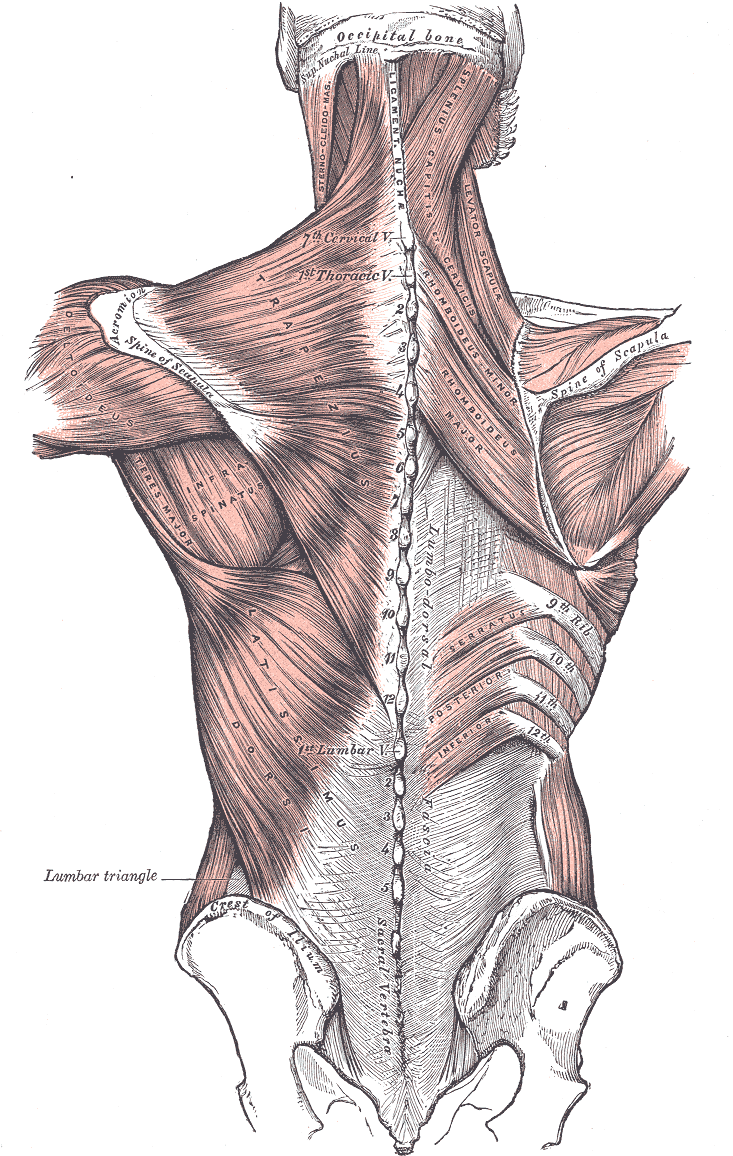

Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2008 Mar:1(1):1-11. doi: 10.1007/s12178-007-9000-5. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19468892]

[3]

Beger O, Dinç U, Beger B, Uzmansel D, Kurtoğlu Z. Morphometric properties of the levator scapulae, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor in human fetuses. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 Apr:40(4):449-455. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2002-8. Epub 2018 Mar 15

[PubMed PMID: 29541801]

[4]

Paine R, Voight ML. The role of the scapula. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2013 Oct:8(5):617-29

[PubMed PMID: 24175141]

[5]

Marecki B, Wosicki J. Morphology of the rhomboid muscle in human fetuses. Folia morphologica. 1987:46(3-4):227-33

[PubMed PMID: 3508144]

[6]

Valasek P, Theis S, Krejci E, Grim M, Maina F, Shwartz Y, Otto A, Huang R, Patel K. Somitic origin of the medial border of the mammalian scapula and its homology to the avian scapula blade. Journal of anatomy. 2010 Apr:216(4):482-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01200.x. Epub 2010 Jan 28

[PubMed PMID: 20136669]

[7]

HUELKE DF. The dorsal scapular artery--a proposed term for the artery to the rhomboid muscles. The Anatomical record. 1962 Jan:142():57-61

[PubMed PMID: 14449723]

[8]

Verenna AA, Alexandru D, Karimi A, Brown JM, Bove GM, Daly FJ, Pastore AM, Pearson HE, Barbe MF. Dorsal Scapular Artery Variations and Relationship to the Brachial Plexus, and a Related Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Case. Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. 2016:11(1):e21-e28. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1583756. Epub 2016 May 10

[PubMed PMID: 28077957]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Tubbs RS, Tyler-Kabara EC, Aikens AC, Martin JP, Weed LL, Salter EG, Oakes WJ. Surgical anatomy of the dorsal scapular nerve. Journal of neurosurgery. 2005 May:102(5):910-1

[PubMed PMID: 15926718]

[10]

Nguyen VH, Liu HH, Rosales A, Reeves R. A Cadaveric Investigation of the Dorsal Scapular Nerve. Anatomy research international. 2016:2016():4106981. doi: 10.1155/2016/4106981. Epub 2016 Aug 15

[PubMed PMID: 27597900]

[11]

Rogawski KM. The rhomboideus capitis in man--correctly named rare muscular variation. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 1990 Aug:67(2-3):161-3

[PubMed PMID: 2216308]

[12]

Galano GJ, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. Surgical treatment of winged scapula. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008 Mar:466(3):652-60. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0086-2. Epub 2008 Jan 8

[PubMed PMID: 18196359]

[13]

Metin Ökmen B, Ökmen K, Altan L. Comparison of the Efficiency of Ultrasound-Guided Injections of the Rhomboid Major and Trapezius Muscles in Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Double-blind Study. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2018 May:37(5):1151-1157. doi: 10.1002/jum.14456. Epub 2017 Oct 19

[PubMed PMID: 29048132]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Sultan HE,Younis El-Tantawi GA, Role of dorsal scapular nerve entrapment in unilateral interscapular pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2013 Jun

[PubMed PMID: 23220342]