[1]

Hunt KJ, Pereira H, Kelley J, Anderson N, Fuld R, Baldini T, Kumparatana P, D'Hooghe P. The Role of Calcaneofibular Ligament Injury in Ankle Instability: Implications for Surgical Management. The American journal of sports medicine. 2019 Feb:47(2):431-437. doi: 10.1177/0363546518815160. Epub 2018 Dec 20

[PubMed PMID: 30571138]

[2]

Fujii T, Luo ZP, Kitaoka HB, An KN. The manual stress test may not be sufficient to differentiate ankle ligament injuries. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon). 2000 Oct:15(8):619-23

[PubMed PMID: 10936435]

[3]

Rigby R, Cottom JM, Rozin R. Isolated calcaneofibular ligament injury: a report of two cases. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2015 May-Jun:54(3):487-9. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2014.08.017. Epub 2014 Oct 16

[PubMed PMID: 25441852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Doherty C,Delahunt E,Caulfield B,Hertel J,Ryan J,Bleakley C, The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 2014 Jan;

[PubMed PMID: 24105612]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[5]

Dimmick S, Kennedy D, Daunt N. Evaluation of thickness and appearance of anterior talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments in normal versus abnormal ankles with MRI. Journal of medical imaging and radiation oncology. 2008 Dec:52(6):559-63. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.2008.02018.x. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19178629]

[6]

Struijs PA, Kerkhoffs GM. Ankle sprain. BMJ clinical evidence. 2010 May 13:2010():. pii: 1115. Epub 2010 May 13

[PubMed PMID: 21718566]

[7]

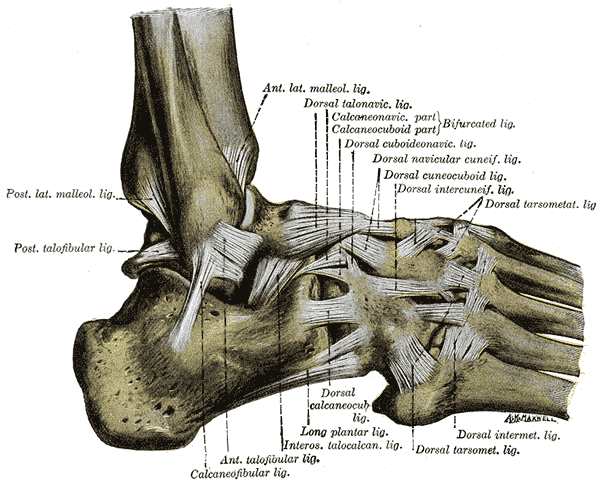

Golanó P, Vega J, de Leeuw PA, Malagelada F, Manzanares MC, Götzens V, van Dijk CN. Anatomy of the ankle ligaments: a pictorial essay. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2010 May:18(5):557-69. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1100-x. Epub 2010 Mar 23

[PubMed PMID: 20309522]

[8]

van den Bekerom MP, Kerkhoffs GM, McCollum GA, Calder JD, van Dijk CN. Management of acute lateral ankle ligament injury in the athlete. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2013 Jun:21(6):1390-5. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2252-7. Epub 2012 Oct 30

[PubMed PMID: 23108678]

[9]

Kovaleski JE, Norrell PM, Heitman RJ, Hollis JM, Pearsall AW. Knee and ankle position, anterior drawer laxity, and stiffness of the ankle complex. Journal of athletic training. 2008 May-Jun:43(3):242-8. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.3.242. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18523573]

[10]

Hubbard TJ, Hicks-Little CA. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. Journal of athletic training. 2008 Sep-Oct:43(5):523-9. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.523. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18833315]

[11]

Bachmann LM,Kolb E,Koller MT,Steurer J,ter Riet G, Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2003 Feb 22;

[PubMed PMID: 12595378]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[12]

Vuurberg G, Hoorntje A, Wink LM, van der Doelen BFW, van den Bekerom MP, Dekker R, van Dijk CN, Krips R, Loogman MCM, Ridderikhof ML, Smithuis FF, Stufkens SAS, Verhagen EALM, de Bie RA, Kerkhoffs GMMJ. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guideline. British journal of sports medicine. 2018 Aug:52(15):956. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098106. Epub 2018 Mar 7

[PubMed PMID: 29514819]

[13]

Petersen W, Rembitzki IV, Koppenburg AG, Ellermann A, Liebau C, Brüggemann GP, Best R. Treatment of acute ankle ligament injuries: a systematic review. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2013 Aug:133(8):1129-41. doi: 10.1007/s00402-013-1742-5. Epub 2013 May 28

[PubMed PMID: 23712708]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[14]

Sugimoto K, Samoto N, Takaoka T, Takakura Y, Tamai S. Subtalar arthrography in acute injuries of the calcaneofibular ligament. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1998 Sep:80(5):785-90

[PubMed PMID: 9768887]

[15]

Thompson JY,Byrne C,Williams MA,Keene DJ,Schlussel MM,Lamb SE, Prognostic factors for recovery following acute lateral ankle ligament sprain: a systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2017 Oct 23;

[PubMed PMID: 29061135]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[16]

Malliaropoulos N, Ntessalen M, Papacostas E, Longo UG, Maffulli N. Reinjury after acute lateral ankle sprains in elite track and field athletes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2009 Sep:37(9):1755-61. doi: 10.1177/0363546509338107. Epub 2009 Jul 17

[PubMed PMID: 19617530]

[17]

Bleakley CM, O'Connor SR, Tully MA, Rocke LG, Macauley DC, Bradbury I, Keegan S, McDonough SM. Effect of accelerated rehabilitation on function after ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2010 May 10:340():c1964. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1964. Epub 2010 May 10

[PubMed PMID: 20457737]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[18]

Bleakley CM, Taylor JB, Dischiavi SL, Doherty C, Delahunt E. Rehabilitation Exercises Reduce Reinjury Post Ankle Sprain, But the Content and Parameters of an Optimal Exercise Program Have Yet to Be Established: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2019 Jul:100(7):1367-1375. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.10.005. Epub 2018 Oct 26

[PubMed PMID: 30612980]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence