Continuing Education Activity

Bilirubinuria is the presence of bilirubin in the urine, usually detected while performing a routine urine dipstick test. Its presence is abnormal and can be the first clinical pointer of serious underlying hepatobiliary disorder even before clinical jaundice is appreciated. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of patients presenting with bilirubinuria and highlights the interprofessional team approach in evaluating and treating this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of bilirubinuria

- Outline the appropriate evaluation of bilirubinuria.

- Review the management options available for bilirubinuria.

- Discuss interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to improve outcomes of patient with bilirubinuria.

Introduction

Bilirubinuria is the presence of bilirubin in the urine. It can be detected by the standardized urine dipstick, mostly referred to as urinalysis in most hospitals worldwide. Bilirubin and related breakdown metabolites are well known for causing the characteristic coloring in bile and stool; however, its presence in the urine is not normal, and for it to be present there, it must be water-soluble and excreted by the kidney. Bilirubin in the body exists as either conjugated/direct or unconjugated/indirect. Unconjugated bilirubin is soluble in fat but insoluble in water and thus cannot be renally excreted. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is characterized by acholuric jaundice as urine is not darkened by urinary bilirubin as bilirubin is not detected in the urine in such cases. On the other hand, conjugated bilirubin is water-soluble and thus can be renally excreted and detected in the urine. Patients may describe their urine as tea or cola-colored when they have jaundice and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia due to liver or biliary disease. In a healthy individual with normal liver function and bile duct anatomy, bilirubin is not detectable in the urine. Therefore, bilirubinuria is a marker of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and can be the earliest sign of hepatic or biliary disease.[1]

Etiology

Bilirubin metabolism occurs in three phases: prehepatic, intrahepatic, and post-hepatic. Bilirubin is conjugated and becomes water-soluble in the liver and is then excreted through the biliary and cystic ducts to either become stored in the gallbladder or pass through the duodenum. Hence conjugated hyperbilirubinemia occurs when there is a disease process that affects the hepatic and post-hepatic phase of bilirubin metabolism.

Intrahepatic causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia include:[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Hepatocellular disease

- Viral hepatitis (Hepatitis A-E)

- Alcoholic liver disease (alcoholic steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis)

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Wilson disease

- Hemochromatosis

Hereditary causes

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome

- Rotor syndrome

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Ischemic hepatitis

Sarcoidosis

Pregnancy

Drug-induced liver injury

Sepsis

Extrahepatic causes of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia include[8][9][10]

Intrinsic to the ductal system

- Gallstones

- Biliary stricture

- Biliary atresia

- Choledochal cyst

- Cholangitis (bacterial, recurrent pyogenic, primary sclerosing, secondary sclerosing)

- Cholangiocarcinoma

- Intrahepatic malignancy

Extrinsic to the ductal system

- Extrahepatic malignancy (lymphoma, pancreatic cancer)

- Chronic pancreatitis

Epidemiology

It is difficult to accurately estimate the incidence and prevalence of bilirubinuria, as it is a laboratory abnormality associated with a number of different clinical etiologies. It is estimated that 3.9% to 6.9% of Americans have some form of chronic liver disease. However, bilirubinuria can also be present in patients with acute liver and biliary disease. It can be observed in patients with unrelated systemic illnesses.

Pathophysiology

To understand the presence of bilirubin in the urine, it is important to understand the physiology behind bilirubin metabolism which can be divided into three phases: prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic.[11][12][13]

Prehepatic

The body produces 4 mg per kg of bilirubin from the metabolism of heme. 80 percent of heme is generated from the catabolism of RBC, and the remaining 20 percent is generated from ineffective erythropoiesis and breakdown of muscle myoglobin. Through a series of reactions, heme becomes biliverdin, which is then transformed into bilirubin and transported from the plasma to the liver for conjugation.

Hepatic

The bilirubin released from the reticuloendothelial system that reaches the hepatocyte is unconjugated/insoluble and is bound to albumin. Once it reaches the hepatocyte, the albumin-bilirubin bond is broken, and the bilirubin is taken by the hepatocyte using a carrier-membrane transport. Once in the hepatocyte, the unconjugated bilirubin is taken to the endoplasmic reticulum, where it is conjugated with a sugar via the enzyme glucuronosyltransferase and is then soluble in the aqueous bile. The conjugated bilirubin is then excreted into bile. The canalicular excretion of bilirubin is the rate-liming step of hepatic bilirubin metabolism; accumulation of conjugated bilirubin in blood signifies hepatocellular dysfunction when the canalicular excretion of bilirubin is overwhelmed or obstruction of the bile duct.

Posthepatic

The conjugated/soluble bilirubin is transported through the biliary and cystic ducts to the gallbladder where it gets stored, or it passes through the ampulla of Vater to enter the duodenum. In the intestines, the bilirubin gets metabolized by the colonic bacteria into urobilinogen, eighty percent of which gets excreted into feces as stercobilin, given its unique color. From the remaining twenty percent, ten percent of it is excreted in the urine as urobilin, given the urine its unique color, and ninety percent of it is unconjugated and undergoes enterohepatic circulation.

In a normal physiological state, conjugated bilirubin is not passed in urine. If there is hepatocellular dysfunction or biliary obstruction, some of the direct conjugated bilirubin escapes into the bloodstream, gets filtered by the kidneys, and excreted in the urine. Thus, bilirubinuria is an important early sign of a pathological process.

History and Physical

A thorough medical history involving assessment of any condition that may be related to hepatobiliary diseases such as fatty liver disease, pregnancy, viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, celiac disease, thyroid disease, and right-sided heart failure should be obtained. All prescribed and over the counter medications, including dietary supplements and vitamins, should be recorded since they might alter liver function. Bilirubinuria has been seen in patients taking the drug phenazopyridine or the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory etodolac.[14] Surgical history should be taken, especially if the patient has an extensive abdominal past surgical history as well as family history is important to see there are any inherited disorders (Dubin-Johnson and Rotor syndrome). Travel history would give the clinician insight into whether the patient has been into hepatitis endemic regions. Social history with a special focus on alcohol consumption should be sought as they may contribute to hepatic dysfunction. Risk factors for viral hepatitis should also be discussed, including intravenous drug use, high-risk sexual activity, and exposure via needle stick or transfusion.[15] Psychological stress is another important cause of bilirubinuria and can easily be missed.[16]

It is also helpful to categorize the differential as hepatocellular injury versus cholestatic causes. Weight loss and constitutional symptoms are consistent with obstructive malignancy, or a history of immune deficiency, which can cause biliary obstruction from opportunistic infections. Patients with biliary obstruction might also complain of dark brown urine, light-colored stool, or pruritis.[17]

On physical examination, a thorough skin and ocular exam are important to denote the presence of jaundice and scleral icterus. Red flags for chronic liver disease such as stigmata of liver disease (caput-medusae, palmar erythema, spider nevi, gynecomastia) as well as signs of hepatic congestion (palpable hepatomegaly, increased jugular venous pressure, abdominal ascites) may be present.[18]

Evaluation

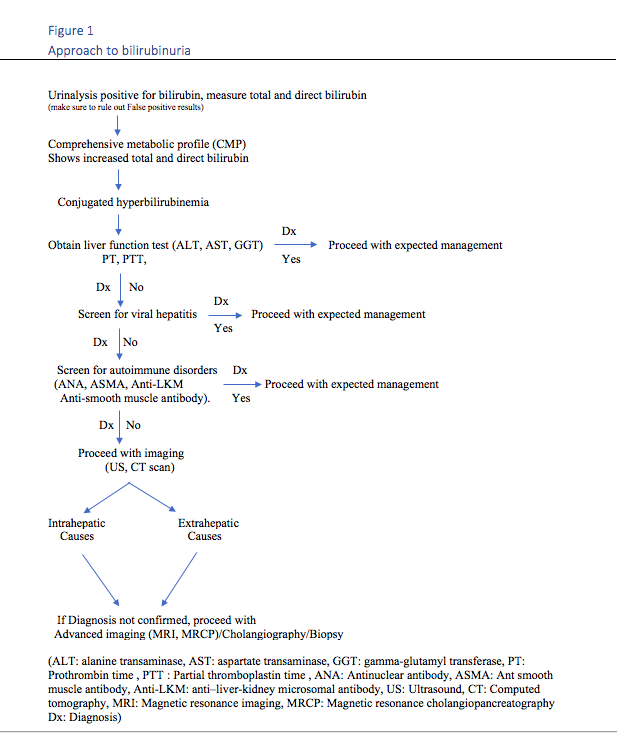

Evaluation of bilirubinuria is performed using a standard urinalysis. In the urine, a chemical strip with a diazonium salt that reacts with bilirubin is used to produce a red azo dye, with the saturation corresponding to the bilirubin value. False negatives can be associated with urinary nitrates, acidic urine with a pH below 5.5, antibiotic use, which decreases the intestinal flora, oxidation by vitamin C, (as bilirubin will not react with the diazonium salts). False positives can be associated with highly colored substances that can mask the results such as phenazopyridine, indicans, chlorpromazine, or etodolac metabolites which cause reddish discoloration of urine. There is no definitive approach for bilirubinuria, A suggested algorithm approach to positive urine bilirubin can be summarized in the diagram below in figure 1.[19][20]

Treatment / Management

The treatment of bilirubinuria is targeted towards the different clinical etiologies responsible for the laboratory abnormality. Liver biopsy is st times needed to determine the cause of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia if blood tests and clinical history do not provide the answer.

ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) is an effective diagnostic and therapeutic procedure performed in patients with bilirubinuria and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia caused by the presence of a common bile duct obstruction such as stone.

Differential Diagnosis

False positives can be associated with highly colored substances that can mask the results such as phenazopyridine, indicans, chlorpromazine, or etodolac metabolites which cause reddish discoloration of urine.[21]

A false-negative test can occur in prolonged cholestasis where despite the presence of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, the predominant fraction of bilirubin which is covalently bound to albumin, delta bilirubin, will not be filtered by the glomerulus.

Prognosis

The prognosis of bilirubinuria depends on the etiology. As a general rule, benign conditions such as gallstones or biliary stricture tends to have a better prognosis compared to malignant biliary obstruction or disease leading to liver cirrhosis.[22]

Complications

Unconjugated bilirubin tends to cross the blood-brain barrier, and because it is lipid-soluble, it can penetrate neuronal and glial membranes and may lead to a spectrum of diseases called biliary encephalopathy. Morbidity and mortality associated with conjugated hyperbilirubinemia and bilirubinuria results from the underlying disease process.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Bilirubinuria might be the earliest sign of a pathological process in the liver. It is important for patients to consult with their primary care provider before the use of any herbal supplements, as some of them might be toxic to the liver. It is important to avoid excessive alcohol consumption and the use of intravenous drugs, and it is important to encourage safe sex practices.[23] It is essential to consult a physician and inquire about vaccines and precautions before traveling to the hepatitis endemic area.

Pearls and Other Issues

When unexpected bilirubin is found on urine dipstick, it is important to conduct further investigation by taking a thorough history and physical examination, and order serum liver biochemical test, even if the patient is not exhibiting any signs or symptoms of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

With a wide range of etiologies for bilirubinuria, an entire interprofessional team must work hand in hand to ensure the best outcomes for the patient. Health care workers such as clinicians, nurse practitioners will be involved in finding the etiology and applying the appropriate management. Nurses will observe and educate patients about disease severity and compliance with treatments. Pharmacists will report back to the medical team with the best medication options, medication dose, and duration of treatment as well as side effects, keeping in mind the medication interactions. Case managers and social workers will help patients with substance addiction to join the services needed and become better. An interprofessional team approach will always be the optimal approach to yield the best possible outcomes. [Level 5]