Continuing Education Activity

Nasal bone fractures represent the most common facial bone fractures, accounting for 40 to 50 percent of cases. Nasal fractures are generally associated with physical assault, falls, sports injuries, and traffic accidents. Bony nasal trauma may occur as an isolated injury or in combination with other soft tissue and bony facial injuries. This activity describes the pathophysiology of nasal fractures and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of those injuries.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of nasal fractures.

- Summarize the causes of nasal fractures.

- Review the treatment options for nasal fractures.

- Review the roles that interprofessional team members play to improve outcomes for patients with nasal fractures.

Introduction

Nasal bone fractures are the most common type of facial fracture, representing 40% to 50% of cases.[1][2] Nasal fractures are most typically associated with physical altercations, falls, sports injuries, and motor vehicle accidents.[3] Bony nasal trauma may present as an isolated injury or occur in combination with other soft tissue and bony facial injuries.[4] Nasal fractures are twice as common in males as females. The protrusion of the nasal bones out of the facial plane and the structure's central location within the face predisposes the nose to injury. Although isolated nasal fractures are the most common facial fractures, they may be associated with fractures of the zygomatic-orbital-maxillary complex and fractures of the skull base; the astute clinician will bear this fact in mind when assessing a patient.

Anatomy and Physiology

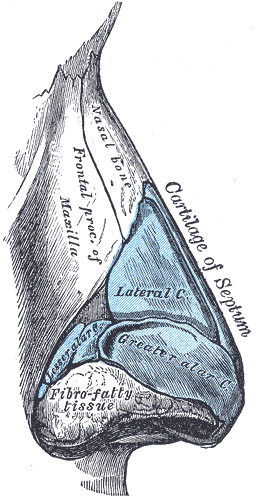

The nose is made up of bony and cartilaginous frameworks. The bony nasal pyramid consists of paired nasal bones and the bilateral frontal processes of the maxillae. Cartilaginous structures include the upper lateral cartilages, which articulate with the inferior edges of the nasal bones, and the lower lateral (or alar) cartilages that make up the nasal tip. Supporting the external nose and continuing beneath the midline of the bony nasal vault is the septum, which is composed of bony and cartilaginous portions. Both the cartilage and the bone of the external nasal skeleton are susceptible to fracture.

Nosebleeds commonly occur with nasal fractures. The blood supply to the nose originates from branches of both the internal and external carotid arteries. Arising from the internal carotid artery is the ophthalmic artery, which in turn gives off the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries that travel from the orbits medially along the skull base to the superior aspect of the nasal septum. The facial and internal maxillary arteries branch from the external carotid artery. The facial artery further branches into the superior labial artery and the sphenopalatine and greater palatine arteries.[5] Trauma to the nose may cause anterior septal bleeding from Kiesselbach's plexus, which is an arterial network located on the anteroinferior nasal septum. Vessels that contribute to the plexus include:

- The anterior ethmoidal artery, which is a branch of the ophthalmic artery

- The sphenopalatine artery, which is a branch of the maxillary artery

- The greater palatine artery, also a branch of the maxillary artery

- The superior labial artery, a branch of the facial artery

This plexus of vessels is clinically significant, as more than 90% of patients presenting with epistaxis will experience bleeding from this area. Trauma to the nasal bones can also cause transection of the anterior ethmoidal artery with resultant brisk, heavy intermittent bleeding. This may require the artery to be clipped and is, fortunately, a very rare occurrence. A blow to the face forceful enough to produce a nasal fracture may also produce fractures of the orbits, maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinus, and cribriform plate as well.

Classification of Nasal Trauma

Nasal fractures can be classified on a scale that stratifies the severity of the injury.[6] An isolated nasal bone fracture is usually caused by low-velocity trauma. If the nose is fractured by high-velocity trauma, facial fractures are more likely to occur concurrently.

- Type I: Injury limited to soft tissue

- Type IIa: Simple, unilateral nondisplaced fracture

- Type IIb: Simple, bilateral nondisplaced fracture

- Type III: Simple, displaced fracture

- Type IV: Closed comminuted fracture

- Type V: Open comminuted fracture or complicated fracture

Indications

History

A thorough history should document the mechanism of the injury as well as the vector in which the force was applied and determine whether there have been any prior nasal traumas or surgeries. It is also important to elucidate whether the patient experiences any nasal obstruction after the injury.

In the acute phase, the simple application of ice and analgesia may be very helpful for reducing edema and discomfort. More severe facial trauma may require assessment and stabilization of the airway, using appropriate Advanced Trauma Life Support or Pediatric Advanced Life Support protocols.

Physical Examination

A general examination is always performed to rule out severe, life-threatening conditions. Additionally, the following examinations should be performed:

Inspection of the Nose and Face

- Deformity and swelling

- Ecchymosis

- Epistaxis

- The shape of the nose: loss of anterior projection of nose with increased intercanthal distance suggests the presence of a naso-orbital-ethmoid fracture

- Eye movements: orbital blowout fractures may cause extraocular muscle entrapment and resulting gaze restriction

Palpation

- Tenderness: widening of the tip of the nose and nasal obstruction may represent a septal hematoma

- Mobility of the nasal bones

- Deformity

- Crepitus

- Bony step-offs

- Infraorbital paresthesia

Examination of the Nasal Cavities

- Elevate the tip of the nose in order to visualize the anterior aspect of the nasal cavities.

- Use a headlight and a nasal speculum or an otoscope.

- Ecchymosis and edema of the nasal septum likely indicate a septal hematoma, which will require emergency drainage.

- The presence of clear nasal fluid may indicate a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak from an associated basal skull fracture; a halo test can raise or lower suspicion for this diagnosis, as can detection of glucose in the fluid.

- Mid-face instability or dental malocclusion may be indicative of a Le Fort fracture.

Imaging

Imaging for isolated nasal fractures is rarely needed, and plain films are of dubious value; the diagnosis of a nasal fracture is typically made based on clinical observation alone.[7] Computed tomography (CT) scans are performed for suspected head injuries, basal skull fractures, or complex facial injuries.[8]

Management

Soft Tissue Injury

Nasal wounds are cleaned and foreign bodies removed. Small lacerations can be closed with porous surgical tape strips, skin glue, or fine sutures.

Nasal Fractures

Reduction of nasal fractures is not always required. No further intervention is needed if there is no deformity or the patient is unconcerned about the aesthetic appearance. However, it is worth counseling patients that the wear of spectacles may be affected by a change in nasal shape. If swelling interferes with an adequate examination, a reassessment should occur 5 to 7 days later, after the patient has had a chance to apply ice and keep their head elevated. For particularly severe edema, a short course of oral steroids may be helpful. Reduction of displaced bone fragments should occur within two weeks of injury, as the nasal bones will heal and fixate; manipulation after this point will be challenging and may require osteotomies to mobilize the bones once more. Some authors even recommend CT guidance for the procedure to improve precision and optimize patient outcomes.[9]

Septal Hematoma

An accumulation of blood underneath the mucoperichondrial layer of the nasal septum normally presents as pain and nasal obstruction with boggy swelling of the septum. If not drained, a hematoma can lead to septal abscess formation, cartilage necrosis, and even a nasal saddle deformity. Aspiration with a syringe and needle may suffice, but the patient should be followed closely to ensure no more blood collects within the septum. Some cases may require formal drainage in the operating theatre with insertion of a small drain or the use of quilting sutures to obliterate the dead space and prevent reaccumulation.[10]

Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks

Clear rhinorrhoea following nasal trauma should raise suspicion for a CSF leak. The cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone that lies at the top of the bony nasal septum is thin and perforated and therefore prone to fracture with sufficient force applied in the correct vector. Confirmation of the diagnosis is obtained by sending a sample of the clear fluid for β-2 transferrin or β-trace protein. A high-resolution CT scan may help detail the exact pattern of the skull base fracture if present.

Contraindications

Contraindications to a closed reduction of nasal bone fractures include:

- Severely comminuted fractures of the nasal bones and septum

- Open septal fractures

- A fracture that initially presents 2 to 3 weeks or longer after the initial injury

- Nasal bone fractures occurring with naso-orbital-ethmoid or Le Fort fractures that require open reduction

Equipment

Reduction of nasal fractures is comparatively straightforward and does not require many resources in terms of either equipment or personnel.

- Topical decongestant: oxymetazoline, lidocaine with phenylephrine spray

- Local anesthetic infiltration

- Headlight

- Nasal speculum (Vienna, Cottle, Killian)

- Boies or Sayre elevator

- Walsham or Asch forceps

- External splint

- If osteotomies are necessary, a #15 blade, nasal osteotomies, and a mallet

Personnel

The personnel requirement for closed nasal fracture reduction under local and topical anesthesia is limited to a surgeon or emergency medicine physician. A nurse or assistant may be helpful to pass instruments and/or comfort the patient as well, however. Under general anesthesia, a circulating nurse, surgical technician, and anesthesia provider will be required in addition to the surgeon.

Preparation

Preparation for the reduction of nasal fractures involves an informed consent discussion that details the options available to the patient, as well as the risks and the anticipated results. Most nasal fractures can be left to heal on their own, provided the patient understands that a long-term cosmetic deformity and nasal obstruction are liable to result. In the acute period, within about two weeks from the injury, most nasal fractures can be reduced in a closed fashion, but after this period, closed osteotomies or even a formal open rhinoplasty may be required for definitive management. The most common adverse outcome of nasal fracture reduction is dissatisfaction with the result, from a cosmetic or functional standpoint, or both. In the event of dissatisfaction, which occurs in up to 20% of patients, open septorhinoplasty performed at least 3 to 6 months after the closed reduction may be an option.[11] The patient should also expect to experience pain, bleeding, swelling, bruising, and nasal obstruction in the early post-procedure period.

Technique or Treatment

Consideration of Anesthesia

Several studies have investigated the suitability of general anesthesia versus local anesthesia for the reduction of nasal fractures.[12] In many cases, a combination of local and topical anesthesia is sufficient to eliminate any discomfort from the experience, but it is not always possible to achieve absolute analgesia with these methods; for this reason, it is imperative preoperatively to assess the patient's ability to cooperate in the face of discomfort. Inebriated patients may initially seem prepared to endure closed reduction under local and topical anesthesia but may react unpredictably during the procedure; closed reduction of fractures in these patients is ill-advised. Pediatric patients also pose additional challenges, and their procedures should ideally be performed under general anesthesia. Most type IIa to type IV fractures in adults can be successfully reduced with a combination of topical and infiltrative local anesthesia. Ideally, closed reduction is performed 5 to 7 days post-injury to allow the majority of the edema to resolve and facilitate palpation and manipulation of the bony fragments.

Local Anesthetic Technique (as necessary)

Nasal fracture reduction with a combination of topical and local anesthetics in an outpatient/office setting is, in the majority of cases, well-tolerated with regards to pain. Results are comparable to having the procedure done under a general anesthetic.[13][14] Topical agents, such as 4% cocaine or 2% lidocaine, can be applied with cottonoid pledgets packed into the nose. The local anesthetic solution (often 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine) is infiltrated along the lateral aspects of the nasal bones, the premaxilla, and intranasally along the septum. Additional key injections will block the infraorbital nerves as well as the infratrochlear and dorsal nasal nerves.[13] The infraorbital nerves are reliably accessed via needle placement through the nasofacial isthmus, halfway between the alar-facial groove and the apex of the nasolabial fold, aiming superolaterally towards the infraorbital foramen, which is located roughly 5 mm below the infraorbital rim, in the mid-pupillary line. The infratrochlear nerves can be addressed as they exit the orbit at the superomedial aspect of the orbital rim, below the head of the brow. Lastly, the dorsal nasal nerves emerge from underneath the nasal bones 6 to 10 mm lateral to the rhinion and are easily anesthetized percutaneously.[15][13]

Closed Reduction

This is the most straightforward approach, with success rates of 60% to 90%; it is usually reserved for simple, noncomminuted fractures.[16] The fundamental principle is to apply a force opposite to the vector of trauma to achieve fracture reduction. Depressed segments of nasal bone can be reduced using an elevator. Alternatively, Walsham forceps can be inserted into the nasal cavity and rotated laterally to press the bones outward. Remember that sometimes the fracture line has to be widened first and then closed again afterward, especially if bones are overriding each other. Attention should be paid to the nasal septum, and where possible, the septal base should be repositioned into the vomerine groove as necessary. In the event that the patient is unable to undergo reduction within 10 to 14 days of injury, the bones may begin to set in an incorrect position; in these cases, osteotomies may be necessary to mobilize the bones, but osteotomies in and of themselves do not necessarily require an open approach to reduction.

All nasal bone reduction patients should wear a dorsal splint for seven days. Not only does it help hold the bones in place, but it reminds the patient and others around them to be careful because the bones can quite easily displace again with minimal force. Most closed reductions do not require internal splints, but they may be useful in cases of comminuted fractures, septal dislocation, and inwardly collapsing nasal bones.

Open Reduction

Fractures that cannot be reduced adequately by closed techniques are candidates for reduction via open septorhinoplasty.[17][18] Occasionally, the bony and cartilaginous injuries may be complex and require extensive manipulation, including grafting, osteotomies, and careful suturing in order to avoid leaving the patient with ongoing nasal breathing or aesthetic issues. The greater exposure and direct visualization afforded by an open rhinoplasty approach offer a major advantage over closed reduction for appropriate patients. When contemplating formal septorhinoplasty to correct traumatic deformities, waiting 3 to 6 months after the initial injury is advisable because it will allow enough time to resolve edema and the posttraumatic inflammatory state.

Post Procedure

The external splint should be worn until the follow-up visit, 1 to 2 weeks after reduction. If splints are placed within the nose to assist with septal fracture reduction, these should be removed at the same visit. Patients should be advised that nasal bone fragments remain prone to shifting for up to 2 weeks after reduction and will not be considered fully healed for six weeks. For this reason, contact sports and games involving flying objects (playing catch, tennis, etc.) should be avoided for at least six weeks. Sleeping with the patient's head elevated and avoiding nose-blowing, heavy lifting, strenuous exercise, and bending over with the head below the heart will also help reduce post-procedure edema.

Complications

While nasal fractures are generally quite benign, complications include the following:[17]

- Cosmetic deformity

- Septal hematoma

- Septal abscess

- Avascular necrosis of the septal cartilage leading to saddle nose deformity

- Nasal obstruction

- Fracture of the cribriform plate and CSF rhinorrhoea

Clinical Significance

The nasal bones are the most commonly fractured in the human body. In most uncomplicated cases, closed reduction under local and topical anesthesia or general anesthesia will produce a satisfactory return to pre-traumatic nasal function and appearance. Timing is a critical consideration when addressing these fractures due to the tendency of the bone fragments to fixate in their posttraumatic locations if left in place for more than 10 to 14 days and because of the difficulty associated with closed reduction in the edematous nose if attempted before 3-5 days have passed since the injury. Open septorhinoplasty may be required to alleviate a persistent nasal deformity or nasal obstruction in the event of a failure of closed reduction.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Nasal fractures can often be managed with closed reduction, and a good outcome should be anticipated in the majority of patients. There are exceptions, of course, often occurring in the elderly and pediatric populations. The amount of time that passes between the injury and the closed reduction greatly influences the chances of a successful outcome. While the diagnosis of a nasal fracture is typically made clinically, without imaging, it is critical for the surgeon to determine the nature of the bony fractures and identify any additional injuries that could complicate the reduction or require repair in their own right. Patient outcomes are improved when the surgeon is experienced in treating nasal bone fractures, communicates well with the primary care or emergency care provider, and is supported by a knowledgeable nurse who can guide the patient through the post-procedure period.