Continuing Education Activity

Bone marrow failure (BMF) refers to the decreased production of one or more major hematopoietic lineages, which leads to diminished or absent hematopoietic precursors in the bone marrow and attendant cytopenias. It can be divided into two categories: acquired and inherited. This activity will review the inherited forms in greater detail while briefly mentioning the acquired forms (covered more thoroughly under each specific topic). Inherited bone marrow failure (IBMF) is bone marrow failure that occurs from germline mutations passed down from parents or arising de novo. This activity reviews the pathophysiology of bone marrow failure and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of bone marrow failure.

- Review the evaluation of a patient with bone marrow failure.

- Summarize the treatment options for bone marrow failure.

- Explain the importance of improving coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance care for patients affected by bone marrow failure.

Introduction

Bone marrow failure (BMF) refers to the decreased production of one or more major hematopoietic lineages, which leads to diminished or absent hematopoietic precursors in the bone marrow and attendant cytopenias. It can be divided into two categories: acquired and inherited. This activity will review the inherited forms in greater detail while briefly mentioning the acquired forms (covered more thoroughly under each specific topic).

Inherited bone marrow failure (IBMF) is bone marrow failure that occurs from germline mutations passed down from parents or arising de novo. In addition to symptoms associated with aplastic anemia, such as fatigue, hemorrhage, and recurrent bacterial infections, patients often have extra-marrow features unique to each syndrome.

The most common inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (IBMFSs) are Fanconi anemia (FA), dyskeratosis congenita (DC), Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS), congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (CAMT), Blackfan-Diamond anemia (BDA), and reticular dysgenesis (RD). Others are less common and share features with the inherited bone marrow failure syndromes listed, for example, short telomerase.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Etiology

Inherited bone marrow failures occur secondary to germline mutations passed down from parents or arising de novo. Most are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner (Fanconi anemia, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia, reticular dysgenesis) while a small subset is inherited in X-linked recessive (dyskeratosis congenita, 2% of FC) or autosomal dominant patterns (Blackfan-Diamond anemia, reticular dysgenesis).[7][1][2][3][5][8]

Epidemiology

Bone marrow failure has triphasic peaks: at 2 to 5 years (inherited is most common), between 20 to 25 years, and after 65 years (most likely due to acquired causes). The incidence of inherited bone marrow failures accounts for 10% to 15% of marrow aplasia and 30% of pediatric bone marrow failure disorders, with approximately 65 cases per million live births every year. The majority of children with inherited bone marrow failures have an identifiable cause (75%). Patients can present as adults. The most common inherited bone marrow failure is Fanconi anemia which occurs in 1 to 5 cases per million with a carrier frequency of 1 in 200 to 300; however, it is more common in Spanish gypsies (1 in 64), Afrikaners in South Africa carrying a specific mutation (1 in 83), and Ashkenazi Jews (1 in 89). Ten percent of patients who present with bone marrow failure have unsuspected Fanconi anemia.[9]

Pathophysiology

Many steps occur for the development of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. There are critical points in hematopoietic lineage pathways. The highly penetrating, specific mutant alleles isolated are of genes that directly affect cell survival and function (routes essential for normal hematopoiesis), in addition to other genetic modifying processes such as cytokine signaling hyperactivity isolated in the pathogenesis of acquired autoimmune aplastic anemia. Lineages most affected are those with frequent division (hematopoietic, gastrointestinal, and integumentary cells), providing the basis behind marrow and extra-marrow pathology observed in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes.

Fanconi anemia involves genomic instability due to mutations in genes coding for DNA damage repair proteins. DNA repair proteins are not oncogenic; however, DNA repair is important in maintaining the integrity of the genome, and any abnormalities allow mutations in other genes during the process of normal cell division. Fanconi anemia is part of a group of autosomal recessive disorders characterized by hypersensitivity to other DNA damaging agents (others include Bloom syndrome and ataxia-telangiectasia, both of which are sensitive to ionizing radiation). Of the 13 genes that make up the Fanconi anemia complex, FANC is the most common mutation. A subset of patients has BRCA2 mutations (FANCD1, FANCG, FANCJ, FANCP), associated with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. These proteins are responsible for DNA damage repair via homologous recombination of intrastrand and interstrand DNA crosslinks due to chemical crosslinking agents. When these genes are mutated, crosslinks remain unrepaired, and when they are exposed upon strand separation during cell replication, the chromosomes break. These exposed ends lead to the activation of salvage nonhomologous end-joining pathways, bridge-fusion-breakage cycles, and massive aneuploidy. Some proteins also participate in the stem cell survival pathway in a direct or indirect manner, further influencing cell survival.[7][1]

Dyskeratosis congenita has mutations in genes responsible for encoding proteins and RNAs involved in telomere maintenance (DKC1, TERC, TERT, NOLA2, NOLA3, WRAP53). These are only half of the genes found in patients. Other less commonly inherited bone marrow failure syndromes and 5% to 10% of adult-onset aplastic anemia have mutated telomerase enzymes. Telomerase is involved in cell replication; defects in telomerase result in short telomeres, leading to premature hematopoietic stem cell exhaustion and marrow aplasia. Moreover, short telomeres are present in half of all patients with aplastic anemia due to a combination of mutated telomerase or excessive stem cell replication.[2]

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome involves mutations in Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome (SBDS) gene, responsible for proteins implicated in ribosome biogenesis and mitotic spindle function.

Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia is not associated with chromosome fragility; however, mutations in MPL (myeloproliferative leukemia virus) oncogene leads to thrombocytopenia from absent or reduced megakaryocytes in the bone marrow. MPL is responsible for coding thrombopoietin receptor c-MPL, a regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production.[6]

Blackfan-Diamond anemia includes mutations in gene families RPL and RPS. They are responsible for ribosomal proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis. Similar to those in dyskeratosis congenita, they account for only half of the genes found in patients.[3]

Reticular dysgenesis is one of the rarest and most severe forms of severe common immunodeficiency (SCID) and occurs from a mutation in mitochondrial adenylate kinase 2 (AK2). Patients develop profound leukopenia, especially neutropenia.[8]

Histopathology

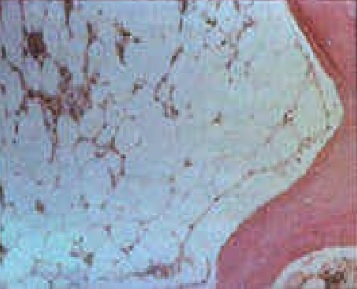

Bone marrow biopsy from patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes who have aplastic anemia will be markedly hypocellular. Fat and fibrotic stroma fill up the remaining marrow space (see image). Any residual hematopoietic cells are predominantly lymphocytes. There may be dysplastic features such as hyponucleated small megakaryocytes, multinucleated red cells, or hypolobulated or hypogranular myeloid cells, none of which are malignant. Some inherited bone marrow failure syndromes affect only one lineage (other lines are well-represented and functional).

History and Physical

Common symptoms of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes are related to aplastic anemia. They include fatigue and pallor due to anemia, hemorrhage secondary to thrombocytopenia, and fevers, mucosal ulcerations, and bacterial infections from neutropenia. Many patients have extra-marrow features specific to each syndrome; however, clinicians cannot rely on the absence of such findings to exclude inherited bone marrow failure syndromes because many patients do not have them.

Fanconi anemia presents in children more often than adults. Patients will have:

- Low birthweight

- Cafe au lait spots

- Short stature

- Microcephaly

- Renal or cardiac malformations

- Hypogonadism

- Absent radii and thumbs

- Histories of bone marrow failure or malignancies, specifically, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), at younger ages (younger than 40 years) in the patient or family members. [7][1]

Dyskeratosis congenita also presents in children more often than adults. While dyskeratosis congenita shares many features with Fanconi anemia (short stature, low birth weight, hypogonadism, and histories of premature malignancies including MDS/AML and SCC), it has the following differences:

- Lacy reticulated skin pigmentation with telangiectasias affecting the upper body

- Maldentition

- Alopecia

- Premature graying of hair,

- Dystrophic nails

- Hyperhidrosis of glabrous skin

- Pulmonary fibrosis[2]

Blackfan-Diamond anemia presents in all ages with bone marrow failure (predominantly neutropenia), exocrine pancreatic dysfunction, and skeletal abnormalities.[3] Congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia patients have histories of thrombocytopenia in infancy (bleeding involving the skin, gut, and mucosal surfaces) progressing to aplastic anemia in later childhood and increased risk of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[6] Blackfan-Diamond anemia presents early in life with isolated erythroid failure more commonly than aplastic anemia and other findings such as low birth weight, bony deformities (triphalangeal thumbs), and short stature. Patients with reticular dysgenesis will have early onset of infections, profound neutropenia, and decreased T and NK cells with absent to low B cells.[3]

Evaluation

In patients with pancytopenia, the first step is to examine the peripheral blood smear for abnormalities, including B12 and/or folate deficiency (hypersegmented neutrophils and oval macrocytes). Next, perform a bone marrow biopsy and aspirate to look for any evidence of myelodysplastic morphology or clonal cytogenic abnormalities. Rule out acquired bone marrow failure by stopping suspected medications, treating active infections, and testing for hepatitis, pregnancy, or paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Patients with bone marrow failure with a positive family history of MDS/AML or SCC, extra-marrow findings associated with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, or age less than 40 years need to be evaluated for inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. It is imperative not to discount these conditions in adults.[10][9]

Screen for Fanconi anemia by the presence of abnormal chromosome breakage in metaphase preparations of lymphocytes or skin fibroblasts cultured with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) dosed with bifunctional DNA interstrand crosslinking agents such as diepoxybutane (DEB) or mitomycin C (MMC). An alternative screening test involves complement analysis using flow cytometry analysis of G arrest in melphalan-dosed cells after transduction. Confirm with gene sequencing.[7][1][11]

The screening test for dyskeratosis congenita is a quantitative analysis of lymphocytic telomere length using flow fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Because it is similar to FA, simultaneously test for chromosomal fragility. Confirm with gene sequencing.[2]

Gene sequencing in other disorders (Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, congenital amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia, DBA, reticular dysgenesis) is mandatory because there are no screening tests. Blackfan-Diamond anemia is associated with increased serum adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels. [3][4][6][5][8]

Other causes of bone marrow failure are acquired. The most common forms occur from drugs, chemicals, radiation, viral infections, immune disorders, MDS, PNH, or large granular lymphocytic leukemia.

Treatment / Management

The definitive treatment for marrow disease associated with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes is hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). Immunosuppressive therapy plays no role. Gene cell therapy may promise a cure in the future.[10][11]

Before undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant, it is important to consider the following: inherited bone marrow failure syndromes are associated with increased mortality using conventional regimens. Patients with FA are highly intolerant of radiation therapy and crosslinking agents in conditioning regimens.

Dyskeratosis congenita and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome individuals suffer excess post-transplant morbidity and mortality, including severe pulmonary and hepatic toxicity. Nonmyeloablative regimens including fludarabine are preferred, though data is sparse. Before the transplant, clinicians must not overlook the diagnosis of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes in siblings who have HLA-matches because the recipient will die. The hematopoietic stem cell transplant will provide no benefit, and the conditioning regimen will be too toxic. Therefore, screen all first-degree relatives of patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes upon diagnosis and refer them for genetic counseling as needed.[2][3]

The exception to treatment is DBA. It is more tolerant of standard conventional treatment and more apt to respond to glucocorticoid treatment (up to 80% of patients). Start with 2 mg/kg/day, then taper after hemoglobin reaches 10 mg/dL and reduce to every other day or discontinue altogether (15% of patients will remain disease-free off steroids).

Supportive care includes infection prophylaxis/treatment and transfusions (leukoreduced red blood cells for Hb less than 7 mg/dL or platelets less than 10,000/microliter or less than 50,000/microliter for active blood loss). Avoid blood products from family members because the risk of alloimmunization increases. Monitor for secondary hemochromatosis and, if needed, administer iron chelators. It is not recommended to use growth factors such as erythropoietin or granulocyte colony-stimulating factors because there are not enough precursor cells to generate satisfactory responses.

For patients wishing to have children, in vitro fertilization is successful and transplanted cord blood from unaffected offspring shows promise in the treatment of Fanconi anemia.[2]

Differential Diagnosis

Other causes of BMF are acquired. The most common forms occur from drugs, chemicals, radiation, viral infections, immune disorders, MDS, PNH, or large granular lymphocytic leukemia.

Prognosis

Survival in IBMFSs depends largely on the age at the time of transplant, disease severity, and response to initial therapy. 10-year survival rates for HSCT are 83%, 73%, 68%, and 51% in the 1, 2, 3, and 5 decades, respectively.[10] 3-year survival in FA is 85% with sibling-matched donors and 50% with unmatched donors using fludarabine nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens.[11] Survival to 40 years in BDA patients approaches 100% patients in remission following steroids, 75% in remission with ongoing steroid use, and 50% with the residual disease despite steroid use. Their 3-year survival is 80% with sibling-matched donors and 20-30% with unrelated matched donors.[3]

Because HSCT only treats marrow disease, patients with IBMFSs are still susceptible to early-onset SCC. Secondary malignancies and complications from pancytopenia (hemorrhage and infections) are the most common causes of death in this population.

Complications

The most common complications of inherited bone marrow failure include bleeding, infections, malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma, and lymphoproliferative disorders. Monitor via surveillance and treat symptomatically with antibiotics, chemotherapy, and/or transfusions.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Inherited bone marrow failure is a spectrum of conditions in which the body cannot make blood cells responsible for infection control, injury repair, and oxygen transport. The diseases run in families but may occur de novo. Patients may also have abnormalities in other organs such as their skeleton and present early in life. Diagnose via history, physical exam, and laboratory testing. Treatment includes bone marrow transplants and additional medications that suppress the immune system and provide blood products to the body. Complications are bleeding, cancers or infections. Inform physicians of any changes.

Pearls and Other Issues

Survival in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes depends largely on the age at the time of transplant, disease severity, and response to initial therapy. Ten-year survival rates for HSCT are 83%, 73%, 68%, and 51% in the first, second, third, and fifth decades, respectively. Three-year survival in Fanconi anemia is 85% with sibling-matched donors and 50% with unmatched donors using fludarabine nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens. Survival to 40 years in Blackfan-Diamond anemia patients approaches 100% patients in remission following steroids, 75% in remission with ongoing steroid use, and 50% with residual disease despite steroid use. Their 3-year survival is 80% with sibling-matched donors and 20 to 30% with unrelated matched donors.

Because HSCT only treats marrow disease, patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndromes are still susceptible to early-onset SCC. Secondary malignancies and complications from pancytopenia (hemorrhage and infections) are the most common causes of death in this population.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bone marrow failure may be acquired or inherited; in both cases, the disorder carries very high morbidity and mortality. The disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an internist, hematologist, oncologist, infectious disease expert, pathologist, laboratory specialist, and internist. These patients are usually monitored by nurses for infections and bleeding. In the long run, the patients are also prone to secondary malignancies. The prognosis depends on the cause of the bone marrow failure. [Level 5]