Continuing Education Activity

Congenital herpes simplex is a rare but potentially devastating viral infection that occurs in newborns and is transmitted from mother to baby during childbirth. Caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV), primarily HSV-2, congenital herpes simplex can result in significant morbidity and mortality if not promptly diagnosed and treated. Despite its infrequency, the consequences of congenital herpes simplex underscore the importance of staying informed and up-to-date on best practices in diagnosis and treatment.

This course will explore key aspects of congenital herpes simplex, including epidemiology and risk factors, clinical manifestations, diagnostic approaches, evidenced-based management, prevention strategies, and long-term prognosis. Healthcare professionals will receive the comprehensive knowledge and skills necessary to better recognize and address this serious condition and optimize outcomes for affected infants and their families. Effective interprofessional teamwork is essential to address the significant implications for neonatal health and well-being, and this review emphasizes collaborative approaches and insights into the pivotal role of a multidisciplinary team.

Objectives:

Identify the etiological factors for congenital herpes simplex.

Assess the various presentations of patients with congenital herpes simplex virus infection.

Apply the latest evidence-based treatment and management options available for patients with congenital herpes simplex virus infections, including dosing and duration of antiviral therapy.

Implement effective collaboration and communication among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes and treatment efficacy for patients with congenital herpes simplex infection.

Introduction

Congenital herpes simplex virus (HSV) is an uncommon but devastating infection in newborns, associated with significant morbidity and mortality depending on the severity of the condition.[1] Newborns often present with nonspecific clinical findings, making timely and accurate diagnosis of infection critical. HSV infection in newborn infants manifests as disseminated disease involving multiple organs, most commonly the liver and lungs, in 25% of patients, localized central nervous system (CNS) disease with or without skin involvement in 30% of patients, and disease limited to the skin, eyes, and mouth (SEM disease) in the remaining 45%. More than 80% of neonates with SEM disease present with skin vesicles. Those patients without skin vesicles have an infection limited to the eyes alone or eyes and oral mucosa. Approximately two-thirds of neonates with disseminated or CNS disease have skin lesions, but other symptoms may be present before these lesions can be seen.

However, diagnosing neonatal HSV infection can be challenging when skin lesions are absent. Disseminated infection is a consideration when neonates present with sepsis syndrome, negative bacteriologic culture results, severe liver dysfunction, or consumptive coagulopathy in the first 30 days after birth. HSV may be the causative agent in neonates who present with a fever, a vesicular rash, or abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings. This probability increases when the infant also has a history of seizures or presents at times when enteroviruses are not reported in the community. Asymptomatic HSV infection is common in older children but rare in neonates. Initial signs of HSV infection can occur anytime between birth and approximately 6 weeks of age, although almost all infected infants develop clinical disease within the first month of life. Infants with disseminated disease and SEM disease have an earlier age of onset, typically presenting between the first and second weeks of life. Infants with CNS disease usually present with illness between the second and third weeks of life.[2][3][4]

Diagnostic confirmation methods include fluorescent antibody staining, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), and monolayer culture with typing. Obtaining positive cultures more than 12 to 24 hours after birth indicates viral replication, suggesting infant infection rather than contamination after intrapartum exposure. The most common treatment for congenital HSV infection is parenteral acyclovir, which should be administered to all neonates with HSV disease, regardless of the specific manifestations and clinical findings.

Etiology

HSVs are enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses primarily consisting of HSV-1 and HSV-2.[5] Infections with HSV-1 usually involve the face and skin above the waist; however, an increasing number of genital herpes cases are attributable to HSV-1. Infections with HSV-2 usually involve the genitalia and skin below the waist in sexually active adolescents and adults. However, either type of virus can be found in either area, and both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can cause herpes disease in neonates. As with all human herpesviruses, HSV-1 and HSV-2 establish latency following primary infection, with periodic reactivation to cause recurrent symptomatic disease or asymptomatic viral shedding.

Factors that can increase the risk of maternal-fetal HSV transmission include the following:

- Type of HSV infection (eg, primary or recurrent infection)

- Maternal serologic status

- HSV typing

- Active HSV at delivery

- Mode of delivery (eg, vaginal versus cesarean delivery)

- Prolonged rupture of membranes

- Fetal scalp electrode use [6]

Epidemiology

The incidence of congenital HSV infection is estimated to range between 1 in 3000 and 1 in 20,000 live births. HSV is transmitted to a neonate most commonly during birth through an infected maternal genital tract but can be caused by an ascending infection through ruptured or intact amniotic membranes. Other less common sources of neonatal infection include postnatal transmission from a parent or other caregiver, most often from a non-genital lesion, for example, on the mouth or hands.[7] The risk of HSV transmission to a neonate born to a mother who acquires primary genital infection near the time of delivery is estimated to be 25% to 60%. In contrast, the risk of a neonate born to a mother shedding HSV as a result of reactivation of infection acquired during the first half of pregnancy or earlier is <2%.[8]

Distinguishing between primary and recurrent HSV infections in women by history or physical examination alone may be impossible because primary and recurrent genital infections may be asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific findings (eg, vaginal discharge, genital pain, or shallow ulcers). History of maternal genital HSV infection does not help diagnose congenital HSV disease because >75% of infants who contract HSV infection are born to women with no history or clinical findings suggestive of genital HSV infection during or preceding pregnancy and who, therefore, are unaware of their infection.

Pathophysiology

HSV is a large double-stranded DNA virus with a surrounding lipid envelope. The DNA in HSV-1 and HSV-2 have many similarities, thus causing much crossreactivity in antibody production. The virus enters the body through epithelial cells or mucous membranes. When HSV has replicated within the nucleus of cells, the virus travels down the axon to the neurons, where a latent infection is established.[9]

Histopathology

Histologic examination of lesions with a Tzanck smear has low sensitivity but may demonstrate multinucleated giant cells and eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions typical of HSV.

History and Physical

Congenital HSV infection can be clinically challenging due to the early manifestations often being subtle and nonspecific. The cutaneous findings include scarring, active lesions, hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, cutis aplasia, and macular rashes. An ophthalmic examination may reveal microphthalmia, retinal dysplasia, optic atrophy, and chorioretinitis. Neurologic findings include microcephaly, encephalomalacia, hydranencephaly, and intracranial calcifications. Congenital HSV can mimic other diseases, including bacterial illnesses (eg, sepsis or meningitis) and other viral illnesses, particularly enterovirus. Congenital HSV infection is classified by its clinical manifestations as skin, eye, and mouth (SEM), central nervous system (CNS), or disseminated disease.

SEM disease typically presents in the second to third week of life. The most common presenting sign is vesicular lesions on an erythematous base. Conjunctivitis is often present, and, left untreated, it may develop into herpetic keratitis and possibly even corneal blindness. SEM has low mortality but reoccurs in 90% of patients.

Affected infants with CNS manifestations may initially have a fever, poor feeding, or present with a sudden episode of seizures or apnea. Between 60% and 70% of babies classified as having CNS disease have associated skin lesions at some point in the course of their illness.

Infants with disseminated disease often present in the first 3 weeks of life with symptoms of sepsis. Multiple organ systems can be affected by this illness, causing jaundice, abnormal liver function, hypoglycemia, hypotension, coagulopathy, pneumonia, and even respiratory failure. Encephalitis is present 75% of the time in disseminated disease, thus causing seizures. Death usually results from shock, progressive liver failure, severe coagulopathy, respiratory failure, and progressive neurological deterioration.[10]

Prompt treatment requires early consideration of congenital HSV as a possibility in neonates with mucocutaneous lesions, CNS abnormalities, or a sepsis-like picture. Early in the clinical course, some neonates with HSV infection may present with persistent fever and negative bacterial cultures.[11][12][13][14]

Congenital HSV infection should be suspected in neonates and infants up to 6 weeks of age with any of the following:

- Mucocutaneous vesicles

- Sepsis-like illness (eg, fever or hypothermia, irritability, lethargy, respiratory distress, apnea, abdominal distension, hepatomegaly, ascites)

- CSF pleocytosis

- Seizures

- Focal neurologic signs

- Abnormal neuroimaging

- Respiratory distress, apnea, or progressive pneumonitis

- Thrombocytopenia

- Elevated liver transaminases, viral hepatitis, or acute liver failure

- Conjunctivitis, excessive tearing, or painful eye symptoms

Evaluation

Given that HSV grows readily in cell culture, cultures of vesicular lesions and affected sites are preferred for diagnosing congenital HSV. Special transport media allow transport to local or regional laboratories for culture. Cytopathogenic effects typical of HSV infection usually are observed 1 to 3 days after inoculation. Methods of diagnostic confirmation include fluorescent antibody staining, enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), and monolayer culture with typing. Cultures that remain negative by day 5 likely will continue to remain negative.[15]

Positive cultures obtained from any of the surface sites more than 12 to 24 hours after birth indicate viral replication. Therefore, these results suggest infant infection rather than mere contamination after intrapartum exposure. Regardless of disease classification, all infants with congenital HSV disease should have an ophthalmologic examination and neuroimaging to establish baseline brain anatomy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive neuroradiologic imaging modality but also may require sedation, so computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography of the head are acceptable alternatives.[6] Routine audiology screening should occur for all infants infected with HSV.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay can often detect HSV DNA in CSF from neonates with CNS infection and older children and adults with HSV encephalitis (HSE); PCR is the diagnostic method of choice for CNS HSV involvement. PCR may also be used to diagnose HSV from skin lesions. However, PCR assays of CSF can yield negative results in cases of HSE, especially early in the disease's course.[16] In complex cases in which repeated CSF PCR assay results are negative, histologic examination and viral culture of a brain tissue biopsy specimen are the most definitive methods of confirming the diagnosis of HSE. Detection of intrathecal antibodies against HSV also can assist in the diagnosis. Viral cultures of CSF from a patient with HSE typically are negative.

To diagnose congenital HSV infection, surface specimens should be obtained as follows: [6]

- Swab specimens from the mouth, nasopharynx, conjunctivae, and anus as "surface cultures" for HSV culture and, if desired, for HSV PCR assay

- Specimens of skin vesicles for HSV culture and, if desired, for PCR assay

- CSF sample for HSV PCR assay

- Whole blood sample for HSV PCR assay

- Whole blood sample for measuring alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

Infants presenting with seizures should be evaluated with an electroencephalogram (EEG), which may show periodic epileptiform discharges.

Treatment / Management

Parenteral acyclovir is the standard of care in treating congenital HSV infection. This treatment should be administered to all neonates with HSV disease, regardless of the specific manifestations and clinical findings. The recommended dosage of acyclovir is 60 mg/kg per day in 3 divided doses (ie, 20 mg/kg per dose); however, the duration of treatment depends on the type of HSV present. For infants with SEM disease, acyclovir should be given intravenously for 14 days. Infants with CNS disease or disseminated disease should be given acyclovir intravenously for a minimum of 21 days.[17] All infants with CNS involvement should have a repeat lumbar puncture performed near the end of therapy to document that the CSF is negative for HSV DNA on PCR assay. In the unlikely event that the PCR result remains positive near the end of a 21-day treatment course, intravenous acyclovir should be administered for another week, with repeat CSF PCR assay performed near the end of the extended treatment period and another week of parenteral therapy if it remains positive. Consultation with an infectious diseases specialist is warranted in these cases.[18]

Oral acyclovir suppressive therapy for the 6 months following treatment of acute congenital HSV disease improves neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with HSV CNS disease and prevents skin recurrences in infants with any disease classification of congenital HSV. Infants surviving congenital HSV infections of any classification of infection (ie, disseminated, CNS, or SEM) should receive oral acyclovir suppression at 300 mg/m² per dose, administered 3 times daily for 6 months; the dose should be adjusted each month to account for growth.[19] Furthermore, the absolute neutrophil count should be assessed at 2 and 4 weeks after initiating suppressive therapy and then monthly during treatment. Longer durations or higher doses of antiviral suppression do not further improve neurodevelopmental outcomes. Valacyclovir has not been studied for longer than 5 days in young infants, so it should not be used routinely for antiviral suppression in this age group. Infants with ocular involvement attributable to HSV infection should receive a topical ophthalmic drug (eg, 1% trifluridine, 0.1% iododeoxyuridine, or 0.15% ganciclovir) and parenteral antiviral therapy. An ophthalmologist should be involved in managing and treating acute neonatal ocular HSV disease.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of congenital HSV can be broad, depending on the clinical features present, and include the following:

Skin Lesions

- Erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN) presents multiple erythematous macules and papules (1 to 3 mm in diameter) rapidly progressing to pustules on an erythematous base. The lesions are distributed over the trunk and proximal extremities, sparing the palms and soles. They may be present at birth but typically appear within 24 to 48 hours. The rash usually resolves in 5 to 7 days, although it may wax and wane before complete resolution. The diagnosis of ETN is generally made based on the clinical appearance. It can be confirmed by microscopic examination of a Wright-stained smear of the contents of a pustule that demonstrates numerous eosinophils and occasional neutrophils. However, this usually is not necessary. ETN resolves spontaneously. No treatment is required.

- Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) is less common than ETN. This condition primarily affects full-term Black infants, although it is described in all ethnic groups. The diagnosis of TNPM is usually based on the clinical appearance. Microscopic examination of a Wright-stained smear of the contents of a pustule demonstrates numerous neutrophils and, in contrast with ETN, rare eosinophils. However, this is usually not necessary. Culture, if performed, yields no organism.

- Infantile acne is an uncommon and distinct entity from neonatal cephalic pustulosis, which typically presents at 3 to 4 months of age but may rarely occur in the first few weeks of life.

- Miliaria is a common condition in newborns, especially in warm climates. It is caused by an accumulation of sweat beneath eccrine sweat ducts obstructed by keratin at the level of the stratum corneum.

- Infantile acropustulosis (IA) is a benign vesiculopustular condition with an often more chronic course than other benign neonatal lesions. The etiology is unknown. A nonspecific hypersensitivity reaction to scabies has been postulated because many patients have been treated for scabies before being diagnosed with IA.

- Congenital sucking blisters, a diagnosis of exclusion, are noninflammatory, oval, thick-walled vesicles or bullae that contain sterile fluid. The lesions may be unilateral or bilateral and typically are located on the dorsal or radial aspect of the wrists, hands, or fingers of neonates who are noted to suck excessively at the involved regions.

Eye Disease

- Viral conjunctivitis due to adenovirus or enterovirus

- Bacterial conjunctivitis (eg, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae)

CNS Disease

- Bacterial meningitis

- Viral meningoencephalitis other than HSV, particularly enterovirus and parechovirus

- Inborn errors of metabolism

Disseminated Disease

- Sepsis due to bacterial etiology

- Adenovirus or enterovirus and parechovirus

- Viral hepatitis other than HSV, drug-induced hepatitis, or causes of neonatal liver disease

- Other neonatal infections (eg, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, and Rubella)

Prognosis

The prognosis of congenital HSV infection is contingent upon several factors, including the timing of maternal infection, the promptness of diagnosis, and the extent of neonatal organ involvement. Infants with mild or asymptomatic cases may have a more favorable prognosis. The best outcomes in terms of morbidity and mortality are observed among infants with SEM disease. Approximately 50% of infants surviving congenital HSV experience cutaneous recurrences, with the first skin recurrence often occurring within 1 to 2 weeks of stopping parenteral acyclovir treatment. However, those with severe manifestations, particularly CNS involvement, face a higher risk of long-term neurological sequelae and developmental challenges.

Early initiation of antiviral therapy (eg, acyclovir) is paramount to improving outcomes, and prompt intervention is associated with a better prognosis.[20] Despite therapeutic efforts, the morbidity and mortality rates for severe cases remain considerable. Ocular complications and neurodevelopmental deficits are potential long-term consequences, emphasizing the importance of long-term follow-up and multidisciplinary care for affected infants. Prevention strategies, including antiviral prophylaxis during late pregnancy and labor in mothers with a history of genital herpes, are crucial in reducing the incidence of congenital HSV infections and alleviating the associated diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Complications

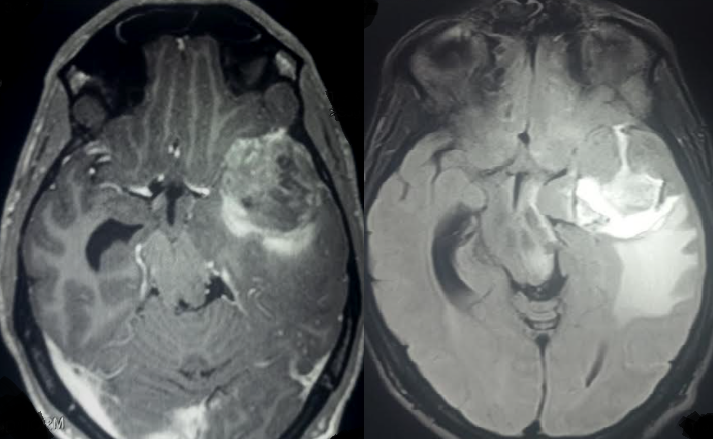

Congenital HSV infection can lead to a spectrum of complications, reflecting the virus's propensity for neural tissue and its capacity to disseminate to various organs. Among the most serious complications is the potential for central nervous system involvement, including encephalitis, which may result in neurological impairment, developmental delays, and long-term cognitive deficits (see Image. Herpes Simplex Encephalitis). Ocular complications (eg, chorioretinitis) can lead to vision impairment or blindness.[21][22] Cutaneous manifestations, including skin lesions, may result in scarring or disseminated infection. Systemic involvement can also affect organs such as the liver, lungs, and adrenal glands, contributing to multiorgan dysfunction. Furthermore, infants with congenital HSV may experience complications related to prematurity, as the infection may prompt preterm labor. Despite advances in antiviral therapy, the risk of mortality and long-term morbidity remains substantial, necessitating early intervention, comprehensive management strategies, and vigilant follow-up care to address the diverse complications associated with congenital HSV infection.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are essential in mitigating the risk of congenital HSV infection. Healthcare professionals play a crucial role in educating pregnant individuals about the importance of HSV during prenatal care and discussing preventive measures to minimize the risk of transmission to the newborn. This includes advising abstinence from sexual activity or the use of barrier contraceptive methods, such as condoms if one partner has a history of genital herpes. Furthermore, educating patients about the signs and symptoms of active HSV infection during pregnancy and the potential consequences for the newborn can facilitate early recognition and prompt medical intervention. The obstetric team should carefully adhere to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommendations for treating and delivering these patients. Empowering patients with knowledge about congenital HSV and preventive strategies empowers them to make informed decisions and take proactive steps to protect their health and that of their infants.

Pearls and Other Issues

For pregnant individuals with active or latent herpes simplex, it is crucial to follow comprehensive recommendations aimed at minimizing the risk of transmitting the virus to the newborn while ensuring maternal and fetal health. These recommendations are as follows:

- Mothers with a known history of HSV should have recurrences treated during their pregnancies to reduce the duration of the recurrences and viral shedding.

- Suppressive viral therapy should be offered at 36 weeks gestation until delivery for patients with an HSV history.

- Spontaneous vaginal deliveries, assisted vaginal deliveries (forceps/vacuum), and internal fetal monitoring during labor are considered safe in patients without active HSV lesions.

- Cesarean delivery is recommended for all obstetric patients with active lesions or prodromal symptoms (eg, vulvar pain or burning).

- In the event of isolated non-genital lesions on the back, thigh, or buttock and after a thorough exam to rule out genital lesions, vaginal delivery may proceed in patients once the lesions are covered with an occlusive dressing.

- In the event of a primary HSV outbreak during the third trimester of pregnancy, the mother should be appropriately treated until after delivery, and Cesarean delivery may be offered due to the possibility of prolonged viral shedding. These patients should be managed in consultation with maternal-fetal medicine and infectious-disease specialists.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of congenital HSV necessitates a strong interprofessional approach. Primary care clinicians, neonatologists, obstetricians, maternal-fetal medicine and infectious disease specialists, nurses, and pharmacists make up the multidisciplinary team. Physicians and advanced practitioners lead in care decisions by possessing the clinical skills necessary for the diagnosis, treatment, and management of congenital herpes simplex. This includes proficiency in recognizing diverse manifestations, interpreting diagnostic tests, administering antiviral therapy, and providing supportive care to affected infants and families. Nurses provide direct patient care, monitor for complications, and educate families. Pharmacists ensure appropriate medication management, while other health professionals may contribute expertise in areas such as nutrition, developmental support, or social services.

Together, the team must develop comprehensive strategies for preventing, diagnosing, and treating congenital herpes simplex. This may involve implementing screening protocols for pregnant individuals, establishing standardized diagnostic and treatment pathways, and coordinating follow-up care for affected infants. Effective communication among team members is essential for ensuring coordinated care and patient safety. Regular interdisciplinary meetings, clear documentation, and open channels of communication facilitate information sharing, care coordination, and collaboration in decision-making. By leveraging the interprofessional team's collective skills, strategies, responsibilities, communication, and care coordination efforts, physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals can enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, ensure patient safety, and optimize team performance in the management of patients with congenital herpes simplex.