Introduction

Why do we sleep? What is the purpose of sleep? Many other questions come to mind when you think about sleep. Sleep is a complex physiological process, in which the body and the mind go in to rest state for some time. Humans spend one-third of their time sleeping and receiving enough of it at the best time, and the right quantity is necessary to survive, just like food and water.

For many centuries, scientists have attempted to answer these questions. Sleep is a complex physiological process, and scientists still do not have a specific explanation of why we sleep, but they know that it is essential for many other physiological processes such as memory consolidation.

Issues of Concern

Understanding the neural mechanisms of sleep is essential because of the crucial role sleep plays in many physiological processes such as memory formation, optimal cognition, immune function, endocrine function, cardiovascular health, and mood. Nearly everyone has had some degree of impaired sleep at some time in their life, but the degree and type of dysfunction dictate the type of impact on health.

Development

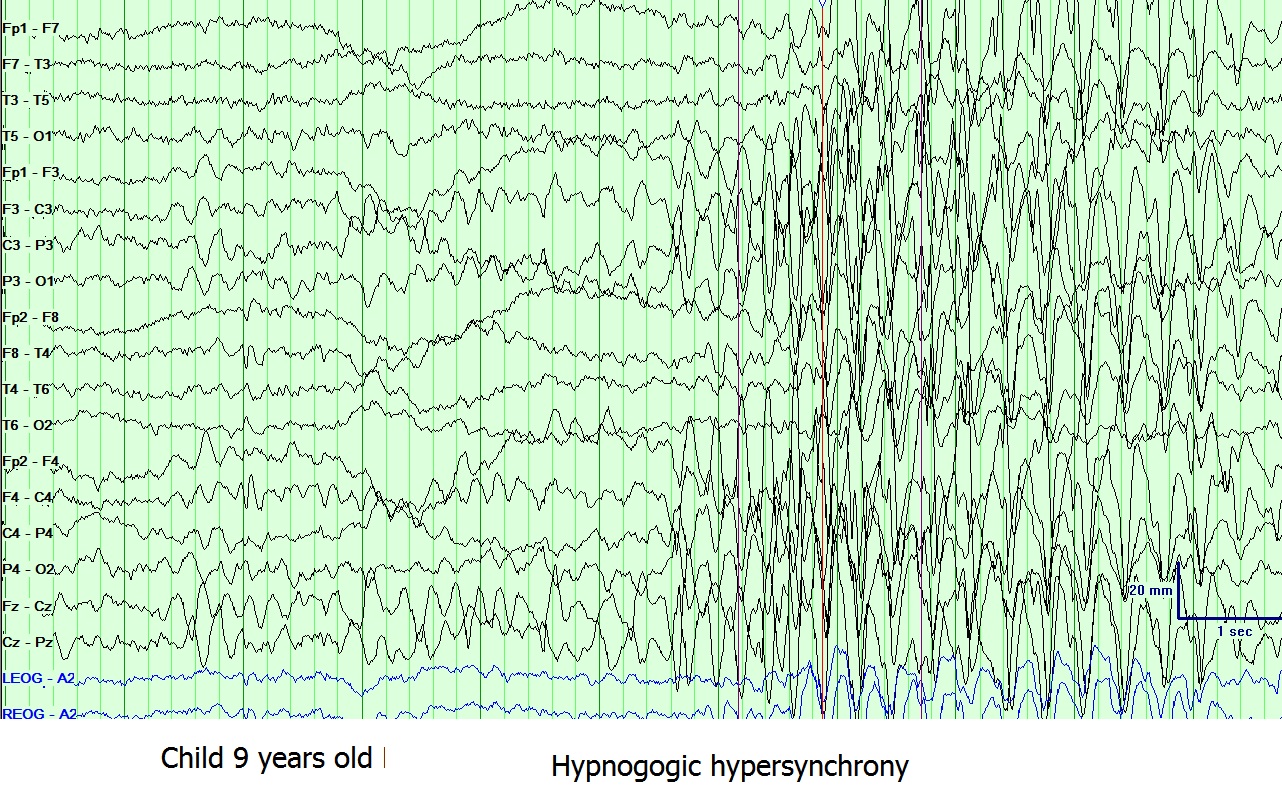

Sleep patterns including, duration, the circadian rhythm, and the ultradian rhythm, are different and change over the first few years of life. Newborns spend most of their day sleeping, and they only wake up to be fed, on the other hand, 1-year-old infants sleep for 10 to 12 hours at night without waking. The coordination between biological rhythm and sleep-wake cycle develops over the first six months of life.[1] In infancy, the sleep stages classify into active, indeterminate, and non-active stages rather than rapid eye movement (REM) and nonrapid eye movement (NREM) stages like adults. Despite these different classifications, they still have similar characteristics.[1]

Function

Sleep stages:

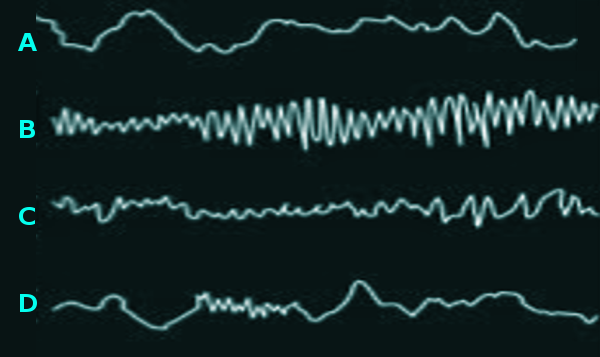

Sleep can be divided into two main stages, the non-rapid eye movement stage (NREM) and the rapid eye movement stage (REM). To differentiate between the different sleep stages and also between sleep in general and the waking state, scientists used electroencephalogram (EEG) to record electrical brain activity across these different states.[2]

Wake stage:When the person is awake, the EEG shows predominantly alpha (7.5 to 12.5 Hz) and beta (12.5 to 30 Hz) activity, and beta activity appears more when the person's behavior requires concentration and attention. Based on this information, the EEG features of alpha and beta activity depend on whether the eyes are closed or opened. During the eye-open wakefulness, the beta wave activity dominates on the anterior leads. As the body becomes more drowsy and the eyes close, there is a progression towards the posterior leads over the occipital regions displaying alpha wave activity predominantly. Eye blinking is common during this phase, which looks like conjugate eye movements consisting of 0.5 to 2 Hz.[2][3][4]

NREM:Scientists divided the NREM stage into three phases; the first phase N1 the second phase N2, and the final phase N3.

N1 phase:This the first phase in the NREM stage, and it is considered the lightest stage because it has the lowest threshold for awakening. It takes from 1 to 5 min and constitutes 5% of the total sleep cycle. The EEG characteristically demonstrates the disappearance of alpha activity and the appearance of theta activity (4 to 7 HZ) and low-amplitude mixed-frequency (LAMF) activity.[2][3][4]

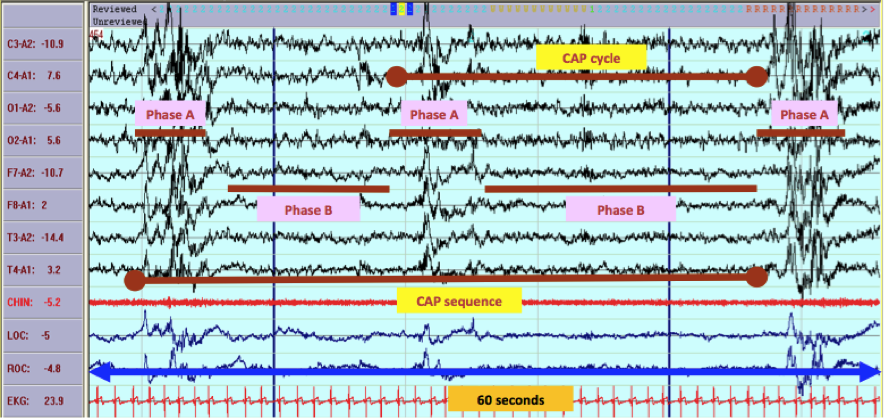

N2 phase:The sleep grows more profound as both the heart rate and the body temperature decline. It continues for about 25 min in the first cycle, and as more extra continuous successful cycles happen, it increases to compose almost 50 percent of the total sleep.The EEG is characterized by the presence of sleep spindles or K complexes or both. K complexes are complicated patterns of sleep waves that resemble a V-shaped with an initial negative wave followed by a positive wave, and it represents the shift into a deeper sleep.[2][3][4]

Sleep spindles are separated discharges of oscillatory neural activity, that range from 11 to 16 HZ (usually 12 to 14 HZ ), in which they progressively grow, then gradually decline, and remains between 0.5 to 3 sec. They are very relevant in the determination of sleep onset, and they occur in both light and deep phases in NREM sleep regularly, every 3 to 6 sec. Sleep spindles are generated in the thalamocortical loop ( thalamus, reticular nucleus, neocortex). The exact functions of sleep spindles are still yet to be determined but are thought to be part of sensory signals shut down during sleep as it suppresses the signals at the thalamic level. Scientists also observed that students who study for more extended periods or learn something new had increased sleep spindles activity, and they think that this improvement helps to strengthen the synaptic interconnections between neurons. Also, recent research suggests that certain types of schizophrenia showed a decrease in sleep spindles activity; thus these types of schizophrenia could be treated by targeting this defect.[5]

N3 phase:In this phase, the deepest sleep occurs with the highest threshold for awakening. The body tends to repair itself and regenerate during this period. If a person gets awaken in this phase, he will suffer from a transient condition called sleep inertia, in which the person will have mild cognitive impairment for about 30 min up to 1 hour.The EEG's characteristic presentation shows a slow frequency high amplitude wave called delta wave ranges from 2 to 4 HZ, and it may also show k complexes and sleep spindles.[2][3][4]

REM stage:The final stage of the sleep, where the skeletal muscle is atonic and immobile, except for the eyes and the diaphragmatic breathing muscle in which they remain active. This stage usually begins after sleeping for 90 minutes, and the initial cycle lasts for about 10 minutes and extends throughout the night to reach 1 hour. The EEG shows sawtooth waves, which are strains of sharply contoured or triangular, often serrated waves of 2 to 6 HZ.

The REM stage can further subdivide into aphasic REM and a tonic REM. The phasic REM gets generated by the sympathetic activity and defined by the presence of rapid eye movements and occasional muscle twitches and changes in breathing patterns, while the atonic REM phase gets produced by the parasympathetic system and lacks the rapid eye movements.[2][3][4][6]

Sleep functions:

Over the past few years, researchers have investigated how sleep affects health, and what's the exact purposes of sleep. Studies have shown that sleep may affect many normal physiological processes in the body and that any interruption in sleep can lead to a variety of problems and diseases and may even cause death.

This section aims to address some of the sleep functions that scientists identified and how sleep deprivation may affect these functions.

Sleep and cardiovascular disease:

Cardiovascular disease is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide. This disease has several risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia. In addition to these main risk factors, studies have shown that people who have sleep disorders like insomnia have an association with cardiovascular disease. The probable mechanism behind this association is that problems like insomnia can increase sympathetic nervous activity as well as causing vascular endothelial dysfunction.[7]

Sleep and the immune system:

Researches have determined that sleep can enhance immune defenses against pathogens. Sleep can affect the immune response primarily through two main ways, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA), and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Circadian oscillation regulates the HPA axis as follows, in the early night during the NREM stage, the HPA activity diminishes, decreasing the production of corticotropin hormone, adrenocortical hormone and eventually cortisol thus increasing the inflammatory response. On the other hand, as the person enters the REM stage, the HPA activity reaches the maximum, thus decreasing the inflammatory response.

Usually, during sleep, there is a marked decrease in sympathetic nervous system activity during NREM stage, and as the REM stage begins, the sympathetic nervous activity starts to rise again. When sleep deprivation occurs, the SNS activity increases throughout the day, increasing the production of noradrenaline and adrenaline, which in turn increasing the inflammatory biomarkers, as well as decreasing the activity and the number of the natural killer cells, one of the most critical innate immune cells.[8]

Sleep is necessary for learning and memory consolidation:

The role of sleep in learning and memory consolidation is still an active research area.[9]

Mechanism

Regulation of sleep and wake:

This section is going to talk about how sleep and wake are regulated and what are the neural circuits involved in these physiological processes. Sleep and wake regulation is by three main components, the brain, the homeostatic process, and the circadian clock.

- Neurobiology of sleep and wakefulness: Neural circuits of wake (the ascending arousal system):

The reticular formation and ascending reticular activating system in the brain stem are critically important for the stimulation and maintenance of wake.[10] The ascending arousal system travels through the paramedian region of the midbrain then divide into two branches, the first branch, is the dorsal pathway, and the second branch is the ventral pathway.[11]

The dorsal pathway arises mainly from pedunculopontine tegmentum and laterodorsal tegmentum and contains mainly cholinergic neurons. It innervates the thalamus specifically, the relay nuclei, and the reticular nuclei.[11] This pathway appears to be necessary for the content of consciousness as it enables the thalamus to process signals related to sensation, motor responses, and cognition then project it diffusely to the cerebral cortex.[12] The reticular nucleus activity in this pathway is very crucial because interactions between this structure and thalamocortical neurons generate specific rhythmic activity in the cortical EEG.[10][13]

The ventral pathway contains the monoaminergic neurons and innervates the lateral hypothalamus, basal forebrain, and the cerebral cortex, respectively. The monoaminergic neurons drive arousal by producing norepinephrine, serotonin, dopamine, and histamine, and they have diffuse innervation to the cortex.[10][12]

The primary source for norepinephrine in the forebrain is locus coeruleus. Locus coeruleus receives inputs from the premotor cortex, brainstem, and other arousal systems and project them diffusely to the cortex. These diverse and multiple inputs and outputs suggest that locus coeruleus serves as a broadcast system that is important for producing a wide range of changes in the behavioral state.[12] As for the forebrain serotonin neurons, they arise from the median raphe nuclei, and dorsal raphe nuclei, they directly excite other wake-promoting neurons to promote wakefulness.[10][12] The dopamine can be produced in many brain regions, thus making it difficult to locate which area is mostly contributing to the arousal. Several researchers proposed that the ventral tegmental area is the primary source of dopamine.[12] The only site in the brain that can produce histamine is in the tuberomammillary nucleus, and histamine neurons promote wake by exciting the cortex, thalamus, and other arousal systems.[12]

Several additional locations may contribute to the above pathways, like the basal forebrain, which consists mostly of cholinergic neurons, and the orexin/hypocretin system. Orexins are neuropeptides found exclusively in the posterior lateral hypothalamus, and they are necessary for maintaining long bouts of awake.[14][13]

Other important areas are lateral hypothalamus and posterior hypothalamus. Unlike the orexins, injuries to these areas cause severe sleepiness, and patients have a decrease in their total amount of wake, and they can sleep up to 15 to 20 hours per day.[14][12]

- Neural circuits NREM sleep:

Several areas researchers identified that promotes NREM sleep mainly, that may also exert some effect on REM sleep, such as the preoptic area, parafacial zone, basal forebrain, and the cortex. The principal neurons that inhibit the arousal system and promote sleep state are GABAergic neurons found in the above mention areas.[12]The most crucial area is the preoptic area, which contains two structures the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) and the median preoptic nucleus (MNPO). The VLPO consists of GABAergic neurons as well as a neuropeptide called galanin, while the MNPO contains only GABAregic neurons. Both areas strongly innervate and inhibit the arousal promoting regions such as the locus coeruleus and the dorsal raphe nucleus.[12][13][11] The basal forebrain, as mentioned earlier, contains chiefly wake active neurons, but they also have GABAergic neurons that are mainly active during sleep, and they promote NREM sleep by inhibiting cortical neurons.[12]Recent research identified another cluster of NREM sleep active neurons found in the parafacial zone, a structure within the medulla oblongata. These neurons are GABAergic/glycinergic, and these neurons project to the parabrachial nucleus as well as the basal forebrain to inhibit it directly.[12]Although most cortical neurons are like the basal forebrain neurons wake active neurons, a small population has been identified to be active during NREM sleep, and these cells are a subset of GABAergic neurons that produce neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). Further research is needed to examine these neurons.[12]

- Neural circuits of REM sleep:

Over the last decade, numerous research groups offered a new model to describe and illustrate how REM sleep is generated and regulated, however, we want to keep in mind, that this model is still incomplete and many questions yet to be solved, so additional research is needed to complete this model.[15] Numerous researchers pointed out that the primary center for the generation of muscle atonia during REM sleep is the sub laterodorsal nucleus, which lies in the pons just ventral to the caudal laterodorsal tegmentum.[15][12][14][11]

For the production of muscle atonia, the glutamatergic neurons project to both the ventral medulla and spinal cord, stimulating the inhibitory interneurons to produce atonia. This circuit is modulated by other brain regions that can either inhibit it, preventing the transition into REM sleep, or enhancing the effect to promote REM sleep.[15]

The most significant region that represses this circuit is the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray matter, which contains GABAergic neurons that project to the sub laterodorsal nucleus to disrupt and inhibit the signal that is going to the ventral medulla or spinal cord.[15]

Another subset of neurons that modulates and promotes REM sleep is the melatonin stimulating neurons that found scattered through the lateral hypothalamus, and these neurons fire maximally during REM sleep only.[15]

- Circadian clock and homeostasis:

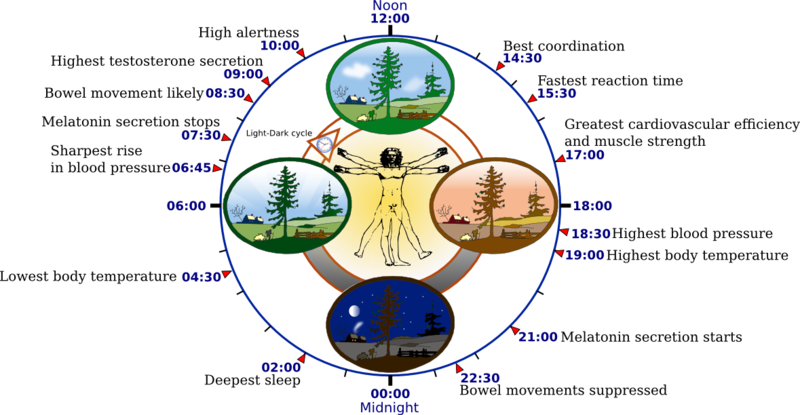

A two-process model developed by Borbely in 1982 demonstrates how sleep-wake is regulated.[16] This model describes that there are two main processes involved in the regulation of sleep, the homostatic process called process s, which represents the sleep dept, and the circadian process, also called process c.[16][14][13] This model proposes that the interaction of process s depending on the previous amount of sleep and wake managed by the process c define the main aspects of sleep regulation.[16]

The underlying mechanisms behind the homostatic process remain unclear, however recent studies, pointed that adenosine in the basal forebrain is a significant modulator for the homeostatic control. Adenosine is a purine nucleoside that is produced by the breakdown of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). When you are awake and working or playing or doing any other activity that requires energy, ATP is being broken down, and adenosine starts to increase and accumulate in the basal forebrain. When adenosine level is high enough, it begins to promote sleep by inhibiting the wake-promoting regions or exciting the sleep-promoting cell groups.[16][13][14][12]

The second component of the two-process model processes c or the circadian clock found in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the most ventral and medial part of the hypothalamus. The SCN is a pair of nuclei situated above the optic chiasm at the base of the third ventricle. The SCN regulates the circadian rhythms based on the light/dark cycle.[16][13][14][12] In the morning, light exposure makes, the circadian clock promotes waking, but as the night arouses, the circadian clock switches to promote sleep because the pineal gland produces melatonin. Most outputs from the SCN project to the subparaventricular zone and the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, which then projected to either wake-promoting areas or sleep-promoting area depending on the situation.[16][13][14][12]

Clinical Significance

Narcolepsy:

Narcolepsy is a rare sleep-brain disorder caused by selective loss or dysfunction of orexin neurons because of infection or trauma. Narcolepsy usually starts in adolescence but in 10 to 15% of patients its starts before the age of 10. Symptoms of narcolepsy can develop in an acute course or chronic course, and they include excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, defined as a brief episode of sudden uncontrollable bilateral loss of muscle tone or weakness. 50 to 60 % of patients with narcolepsy may also report having sleep paralysis and hallucinations.The diagnosis of narcolepsy is based on clinical features. Specific biomarkers support it, and the treatment of narcolepsy often includes both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, with constant routine medical follow up. Non-pharmacological treatment strategies include psychotherapy and behavioral therapy (maintaining regular sleep schedule), as well as self-care. Also, it is advisable for patients to have daily physical activity, in combination with a balanced diet and caffeine intake. As for pharmacological treatment, it focuses on the symptoms. For example, for excessive daytime sleepiness, the first-line drug is modafinil, and for cataplexy sodium oxybate.[17]

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD):

REM sleep behavior disorder is a sleep condition in which patients with this disorder act out in their dreams, a term called dream enactment. RBD is idiopathic and strongly associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia with Lewy bodies. The exact mechanism behind this disorder is still poorly understood. All patients diagnosed with RBD should be informed about sleep safety measures to prevent accidents and injuries. Two main drugs are useful in the treatment of RBD, melatonin, and clonazepam.[18]

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA):

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder that causes breathing to stop spontaneous during sleep because the air cannot infiltrate the lung normally due to the collapse of the soft tissue in the upper airway. Patients with OSA usually are obese and complain of snoring, sudden or jerky body movements, and frequent waking from sleep. They may also experience sore throat, morning headache, fatigue or tiredness throughout the day, and troubles with memory and concentration. Treatment of OSA depends on the cause and severity of sleep apnea it may range from lifestyle modification such as weight loss and alcohol avoidance to requiring the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in severe cases, CPAP is a device the blows air into a mask during sleep to prevent the airway from collapsing.[19]

Jet lag disorder:

Jet lag, also called time zone change syndrome, is a temporary disorder that is caused by quickly passing at least two time zones. Patients usually complain of insomnia or excessive sleepiness. Treatment aims at treating the symptoms by administrating short-acting hypnotics, as well as adjusting the circadian rhythm by practicing good sleep hygiene and avoid excessive alcohol or caffeine consumption.[20]

Shift work disorder:Shift work disorder is a sleep disorder involving circadian rhythm that occurs in people who work outside the period of 6 AM to 8 PM. Symptoms may include insomnia or excessive sleepiness. The current standard care of management includes maintaining good sleep hygiene, and aligning the circadian rhythm, avoid exposure to bright light and excessive alcohol and caffeine consumption, as well as administrating melatonin and short-acting hypnotics.[20]