Continuing Education Activity

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common cutaneous malignancy, affecting close to one in five Americans. Although rarely fatal, basal cell carcinoma can be highly destructive and disfigure local tissues when treatment is inadequate or delayed. This activity describes the risk factors, evaluation, and management of basal cell carcinoma and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in enhancing care delivery for affected patients.

Objectives:

Describe the risk factors for basal cell carcinoma.

Outline the evaluation of basal cell carcinoma.

Summarize the treatment strategies for basal cell carcinoma.

Explain the importance of improving care coordination amongst the interprofessional team to optimize the management of patients with basal cell carcinoma.

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC), previously known as basal cell epithelioma, is the most common cancer in Humans. BCC mostly arises on sun-damaged skin and rarely develops on the mucous membranes or palms and soles. Basal cell carcinoma is usually a slow-growing tumor for which metastases are rare. Although rarely fatal, BCC can be highly destructive and disfigure local tissues when treatment is inadequate or delayed. On clinical examination, BCC usually appears as flesh- or pink-colored, pearly papules with overlying ulceration or telangiectatic vessels. BCC occurs on the head or neck in the majority of cases, but can involve the trunk and extremities.[1][2]

More than 26 different subtypes of BCC appear in the literature, but the more common, distinctive, clinicopathologic types include: nodular, micronodular, superficial, morpheaform, infiltrative and fibroepithelial (also known as fibroepithelioma of Pinkus). Combinations of these types can occur as well. The majority of BCCs are amelanotic, but variable amounts of melanin may be present within these tumors.

The current mainstay of BCC treatment involves surgical modalities such as excision, electrodesiccation and curettage (EDC), cryosurgery, and Mohs micrographic surgery. Such methods are typically reserved for localized BCC and offer high 5-year cure rates, generally over 95%.

Etiology

The prime etiological factor in the development of basal cell carcinoma is exposure to UV light, particularly the UVB wavelengths, but UVA wavelengths can also be a factor. A detailed review of the literature with meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis show a significantly higher risk for outdoor workers, with an inverse relationship between occupational UV exposure and BCC risk with latitude. The Fitzpatrick skin type is a good predictor of the relative risk of BCC among White race individuals.[3][4]

Cumulative UV dose and skin type are not sole predictors; exposure duration and intensity, particularly in early childhood and adolescence, also plays a role in BCC development. Recreational sunlight exposure and the use of indoor tanning salons are a contributing factor for the development of BCCs. UV light therapy may also lead to BCC occurrence. Intermittent intense sun exposure, as identified by prior sunburns; a positive family history of BCC; a fair complexion, especially red hair; easy sunburning (skin types I or II); and blistering sunburns in childhood are also risk factors for the development of BCC.

Ultraviolet light exposure is not the only risk factor as 20% of BCC arise on non–sun-exposed skin. BCCs also occur due to various other factors such as ionizing radiation exposure, arsenic exposure, immunosuppression, and genetic predisposition. Some genetic syndromes associated with an increased risk of BCCs are xeroderma pigmentosum, basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome), Bazex–Dupre–Christol syndrome, and Rombo syndrome.

There is no association with diet, but smoking also appears to be a risk factor in females.

Epidemiology

BCC is the most common skin cancer in humans, with increasing incidence rates worldwide. Men generally have higher rates of BCC than women. BCC is more frequent in geographic locations with greater UV exposure, such as those at higher or lower latitudes. The most common predictor of BCC development is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC. Patients are at least ten times more likely to develop a second BCC if they have a BCC history compared to patients without a history of non-melanoma skin cancer.[5][6]

Over the last 30 years, estimated incidence rates have risen between 20% and 80%. Incidence rates for BCC also increase with age, with the median age of diagnosis being 68 years. Mortality from BCC is uncommon and occurs primarily in immunocompromised patients. Metastatic BCC (1%) is more likely the result of tumors with aggressive histopathologic patterns (morpheaform, metatypical, basosquamous, infiltrating). If a BCC does metastasize, it often involves regional lymph nodes, bone, lungs, and skin. The mean age at the time of death is higher than with SCC, and the estimate for age-adjusted mortality rate is 0.12 per 100 000. The mortality risk is related to increasing age, male gender (greater than twice the rate of occurrence compared with women), and White race phenotype.

Pathophysiology

Chronic sun exposure is among the most critical risk factors for the development of BCC. BCCs typically have a delay of diagnosis of about 15 to 20 years between the time of UV damage and clinical onset.[7]

The mechanism of BCC formation via ultraviolet radiation is direct DNA damage, indirect DNA damage through reactive oxygen species, and immune suppression. Melanin absorbs UVA and indirectly damages DNA through free radicals. UVB directly damages DNA and RNA with a characteristic C/T or CC/TT transition. Ultraviolet exposure also causes dose-dependent suppression of the cutaneous immune system, impairing immune surveillance of skin cancer.

Literature suggests that the cells of origin from which BCC arises are immature, pluripotent cells associated with the hair follicle. Of note, the gene most often altered in BCCs is the PTCH1 gene. PTCH1 gene mutations occur in 70% of people with sporadic BCC. Ten percent to 20% of people with sporadic BCC have smoothened (SMO) mutations. Literature suggests that a sufficiently elevated expression level of Gli, by activating mutations of SMO or by homozygous inactivation of PTCH1 in a responding cell, is sufficient to drive the formation of BCC. The second most common mutation found in BCCs is in the P53 gene. Mutations in CDKN2A locus also have been detected in a smaller number of sporadic BCCs.

Histopathology

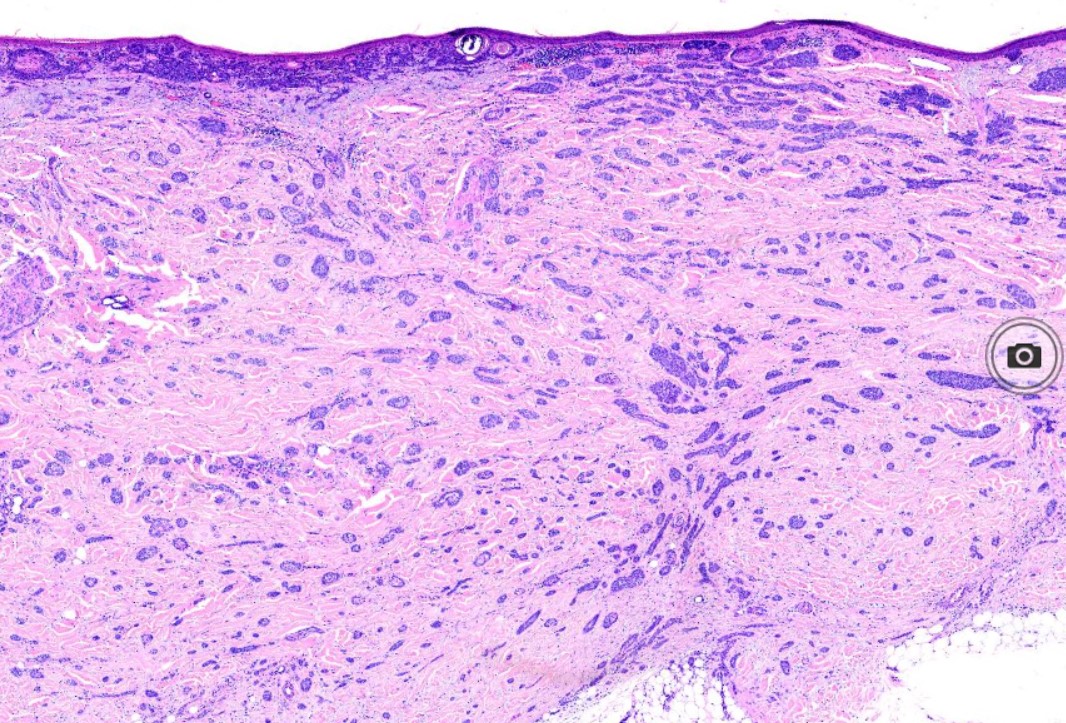

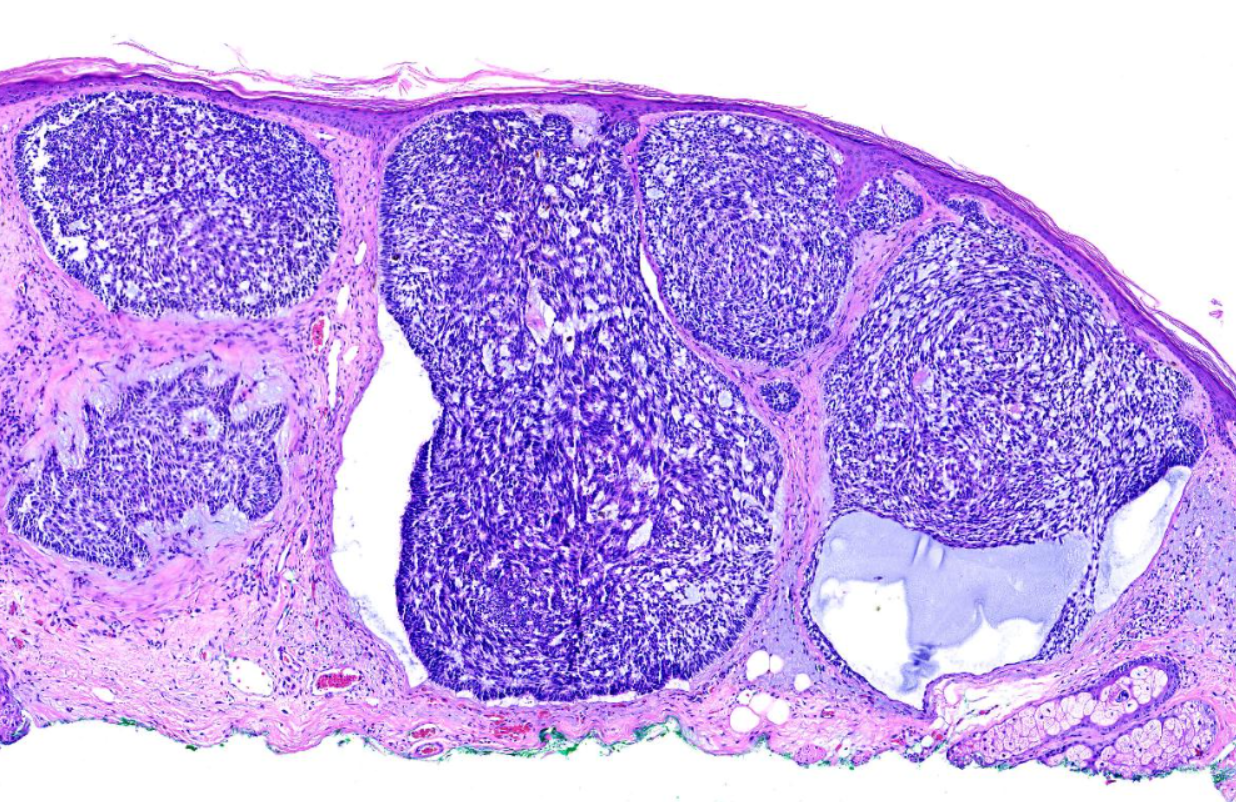

The characteristic feature seen in BCCs is islands or nests of basaloid cells, with cells palisading at the periphery in a haphazard arrangement in the centers of the islands. Each of these small pleomorphic cells is composed of a basophilic nucleus without a discernible nucleolus and scanty cytoplasm. Retraction artifact, also referred to as clefting, is usually is seen between the tumor and its surrounding stroma on paraffin-embedded sections. Mucin deposition may be present within the tumor and in the stroma around the tumor. Mitotic figures also may be present. Perineural growth, also known to as perineural invasion, can be an indicator of aggressive disease.

The histologic differential diagnosis may include trichoepithelioma or trichoblastoma. Various morphological subtypes have been defined, including nodular (solid), micronodular, superficial, cystic, infiltrating, infundibulocystic, pigmented, adenoid, sclerosing, metatypical, basosquamous, and fibroepitheliomatous (see Image. Pigmented Basal Cell Carcinoma). Mixed patterns of the above-listed types are also common.

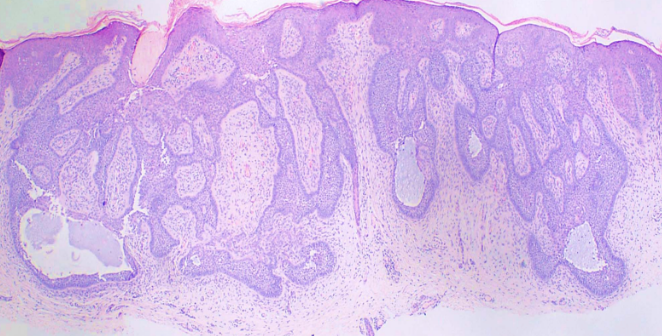

- The superficial subtype has multiple, small buds of basaloid cells descending from the epidermis with no dermal invasion.[8][9]

- The nodular variant accounts for the majority of all cases. Nodular BCCs are composed of islands of cells with peripheral palisading and a haphazard arrangement of the more central cells. Ulceration may be present in larger lesions (see Image. Basal Cell Carcinoma, Nodular).[8][9]

- The micronodular subtype has histologic features similar to those of the nodular subtype, except that it is composed of multiple small nodules. The micronodular type has a much greater risk for local recurrence than the solid type (see Image. Basal Cell Carcinoma with Micronodular and Morpheaform Features).[8][9]

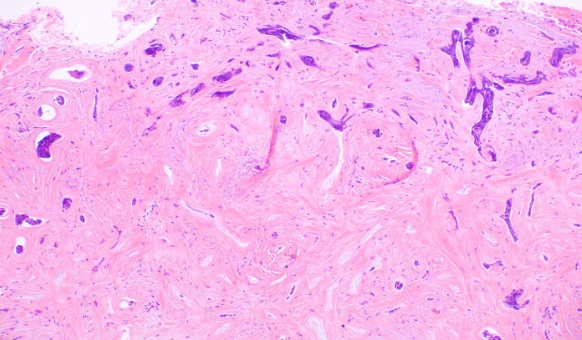

- The sclerosing (morphea-like) subtype is composed of spiky, basaloid, thin strands of cells that invade the dermis, surrounded by dense fibrous stroma. The histologic differential diagnosis may include microcystic adnexal carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, or metastatic cancer. When most of the tumor nests have spiky projections, the tumor may invade deeply, referred to as an infiltrative BCC (see Image. Basal Cell Carcinoma, Morpheaform).[9]

- The pigmented BCC results from the presence of melanocytes and melanin admixed with the tumor cells, which is more common in the superficial, micronodular, or follicular variants.

- The infundibulocystic variant is uncommon and often found on the face. This variant is a small, well-circumscribed tumor composed of nests of cells arranged in an anastomosing manner with little stroma. Numerous small infundibular cyst-like structures contain keratinous material and sometimes melanin.

- Basosquamous or metatypical BCC shows features of both BCC and SCC. The exact nature of this lesion is controversial, but most reserve this term for the rare basal cell carcinoma composed of nests and strands of cells maturing into larger and paler cells without peripheral palisading.

- Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presents as a soft nodular lesion resembling a fibroma or papilloma, commonly on the lower part of the back. It is composed of anastomosing strands and aggregates of basaloid cells surrounded by a fibrous stroma (see Image. Basal Cell Carcinoma, Fibroepthelioma of Pinkus).[8][9]

History and Physical

Many clinical variants of BCC exist, but the most recognized types are superficial, nodular, and morphea-like BCC. Nodular BCC is the most common (see Image. Nodulocystic Basal Cell Carcinoma).

BCC typically presents as a shiny, pink- or flesh-colored papule or nodule with surface telangiectasia. The tumor may enlarge and ulcerate, giving the borders a rolled or rodent ulcer appearance. The most common sites for nodular basal cells are the face, especially the nose, cheeks, forehead, nasolabial folds, and eyelids. Patients often give a history of crusting and recurrent bleeding, causing them to seek evaluation. Pigmented nodular BCCs are more common in dark-skinned individuals.

Superficial BCCs present as a pink-red, scaly, macule or patch, which may contain telangiectasia (see Image. Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma). They have a predilection for the shoulders, chest, or back, and multiple lesions may be present. There are also pigmented variants of superficial BCC. Clinically, superficial BCC can appear similar to inflammatory dermatoses such as eczema or psoriasis, so one should consider the diagnosis of superficial BCC when faced with a persistent, erythematous, scaly plaque. Portions of superficial basal cell carcinomas can evolve into nodular BCC over time.

The other common clinical variant of BCC is the morpheaform subtype. This tumor frequently presents as white- or flesh-colored with areas of induration and ill-defined borders. Morpheaform BCCs may resemble a scar or plaque of morphea. The lesion's surface is typically smooth, although crusts with underlying erosions or ulcerations, as well as superimposed papules, may be observed. Telangiectasias also may be present. The biologic behavior is usually more aggressive, with extensive local destruction.

Evaluation

A skin biopsy is necessary for clinical confirmation of BCC. A shave, punch, or excisional biopsy are all options, taking care to include some portion of the dermis in the specimen to differentiate between superficial and other invasive histologic subtypes of BCC. It should be noted that punch and shave biopsy techniques are about 80% accurate in diagnosing the various subtypes of basal cell carcinoma.[10]

A qualified practitioner should perform a complete skin examination since individuals with one finding of skin cancer often have additional cancers or pre-cancers at other sites and have an increased risk of developing malignant melanoma. Documentation of the location of the lesions with photographs or digital images is a recommended procedure. There is a low threshold for obtaining skin biopsies in these patients. Preoperative imaging studies may be necessary when there is suspicion of parotid gland, muscle, deep soft tissue, orbital, bone involvement, or perineural invasion. Patients with a history of BCC should have long-term, even lifetime, follow-up, particularly those with multiple or high-risk tumors.

Dermoscopy can be beneficial to the experienced clinician, aiding in the diagnosis of non-pigmented and pigmented BCCs. The hallmark of BCC on dermoscopy is the presence of well-focused arborizing vessels. Additional findings include multiple blue-gray globules, leaf-like structures, large blue-gray ovoid nests, and spoke-wheel areas. There is no pigment network, as one would see with dermoscopy of pigmented lesions.

Treatment / Management

Therapy selection depends on the patient's age and gender as well as the site, size, and type of lesion. No single treatment method is ideal for all lesions or all patients. A biopsy should be performed in all patients with suspected BCC to confirm the diagnosis and determine the histologic subtype. The main goals of BCC treatment are (1) to completely remove the tumor to pr

event recurrence at a later date, (2) to correct any functional impairment resulting from the tumor, and (3) to give the best cosmetic result to the patient, especially because most BCCs are on the face.[11]

Treatment of BCC is usually surgical, but some forms of BCC are amenable to medical treatment or radiation therapy. The various types of therapy include Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), standard surgical excision, EDC, radiation, photodynamic therapy, cryosurgery, topical therapies, and systemic medications such as Vismodegib. The recurrence rates for primary BCC are as follows: Mohs surgery, 1.0%; surgical excision, 10.1%; EDC, 7.7%; radiation therapy, 8.7%; and cryosurgery, 7.5%.

Mohs surgery provides the best long-term cure rate of any treatment modality for BCC. MMS is the gold standard for treating high-risk BCCs and recurrent BCCs because of its high cure rate and tissue-sparing benefit. The high cure rate is attributed to an examination of 100% of all the tissue margins when compared with standard vertical sectioning, wich only examines less than 1% of the outer peripheral and deep margins. By only taking thin tissue layers from the areas with positive tumor margins, the wound size is minimized, and a superior cosmetic outcome can be expected.

Postoperative pathologic analysis with permanent sections follows standard surgical excision. Four-millimeter margins are typically adequate for well-circumscribed tumors that are less than 2 centimeters in diameter. For facial lesions, simple excision with narrow margins is often not adequate for effective removal. EDC is frequently used to treat low-risk BCCs. Cure rates are reportedly as high as 97% to 98%, but the clinician should be cautious to select the appropriate cases (those without extension into the deep dermis). BCCs treatment with EDC is the least expensive and fastest treatment method, but because they are left to heal by second intention, the procedure commonly results in a white atrophic scar that can be cosmetically disfiguring.

Radiation therapy is a primary option for treating BCC or SCC if surgery is contraindicated. It also can be used as an adjuvant treatment for basal cell carcinoma when further surgery could sacrifice major nerves or other vital structures, or there is a perineural invasion by cancer cells. The disadvantages of radiation therapy are cost, poor cosmesis in some patients, prolonged course of treatment (15 to 30 visits), and increased risk for future skin cancers. Scars from radiation therapy tend to worsen with time, while surgical scars improve over time.

Cryosurgery is another treatment option for low-risk BCCs. It involves the controlled application of liquid nitrogen to the clinically visible tumor and a small surrounding margin of normal-appearing skin for margin control. A temperature probe can be used and is inserted at the lateral tumor margin, and the tip is positioned position the tip just below the tumor by pushing it obliquely. Next, liquid nitrogen is applied and continued until reaching a temperature of -60 degrees C. In practicality, a temperature is seldom employed during this procedure. The procedure is advantageous for those wishing to avoid invasive surgery, and it is also relatively quick. The treated area may be painful and swollen after it thaws. Cryosurgery also can cause hypertrophic scarring and permanent pigment alteration.

Topical therapy is another treatment for basal cell carcinoma. Topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and Imiquimod 5% cream are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat superficial BCC. Both topical therapies are good options in patients with multiple superficial BCCs and in patients who are poor surgical candidates. Application site reactions are common and include erythema, pruritus, pain, edema, hypopigmentation, hyperpigmentation, crusting, bleeding, and erosions. Another disadvantage is there no histologic confirmation of complete tumor clearance.

A more recent treatment for patients with advanced or metastatic BCC that is untreatable with conventional therapeutic methods is Hedgehog pathway inhibitors. The FDA approved Vismodegib in 2012. A second inhibitor, sonidegib, was also approved. The side effects of vismodegib and sonidegib can lead to discontinuation in up to 55% of patients. The most commonly reported adverse effects included nausea, dysgeusia, muscle spasm, alopecia, weight loss, diarrhea, and fatigue.

In specific populations, such as the immune-suppressed, the elderly, and those with poor baseline functional status and cases of metastatic, advanced, recalcitrant, or cosmetically sensitive disease, nonsurgical management may be a desirable alternative.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of BCC includes adnexal tumors with follicular, sweat gland, or sebaceous differentiation and certain types of SCC. Nodular BCC may be confused with trichoblastoma or trichoepithelioma. Superficial BCC may mimic some inflammatory dermatoses such as psoriasis and eczema. Morphea-like BCC may be confused with a plaque of morphea or a scar. In these cases, histopathological helps to establish the diagnosis of BCC.

Prognosis

BCC is rarely associated with a fatal outcome. Its prognosis is mainly related to its potential risk of recurrence after initial therapy. The risk of recurrence depends on BCC location and BCC clinical and histopathological features.

BCC Location

- Low-risk location: trunk and limbs

- Intermediate risk location: forehead, cheeks, chin, neck, scalp

- High-risk location: centrofacial areas, nose, ears, periorificial areas, embryonic fusion planes

BCC Clinical and Histopathological Features

- These include the size, the histopathological type, and the fact that the tumor is primary or recurrent.

Tumor Prognosis

- Good prognosis: primary superficial BCC, primary nodular BCC <1cm in intermediate-risk location or <2cm in low-risk location;

- Intermediate prognosis: recurrent superficial BCC, nodular BCC <1cm in high risk location or <2cm in intermediate-risk location or >2cm in low risk location;

- Poor prognosis: nodular BCC >1cm in high-risk location (high risk of recurrence), morpheaform, infiltrative or histologically aggressive (very high risk of recurrence), recurrent tumor, except superficial BCC (very high risk of recurrence)

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An evidence-based approach to basal cell cancer

Basal cell cancer is relatively common. Patients often first present to the primary care provider with complaints of an abnormal skin lesion. When diagnosed early, it has an excellent prognosis, but if there is a delay in diagnosis, the tumor can advance and lead to significant morbidity. Basal cell cancer is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a dermatologist, mohs surgeon, plastic surgeon, nurse practitioner, primary care provider, and a dermatopathologist. Basal cell carcinomas typically have a slow growth rate and tend to be locally invasive. Tumors around the nose and eye can lead to vision loss. In most cases, surgical excision is curative. However, because recurrences can occur, these patients need long-term follow up.[12][13]