Continuing Education Activity

Gastroenteritis is a diarrheal disease characterized by an increase in bowel movement frequency with or without fever, vomiting, and abdominal pain. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of gastroenteritis and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of bacterial gastroenteritis.

- Identify the pathophysiology of bacterial gastroenteritis.

- Outline the use of supportive management, antibiotic and symptomatic therapy in the management of bacterial gastroenteritis.

- Summarize the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by bacterial gastroenteritis.

Introduction

The word "gastroenteritis" originates from the Greek word gastron, meaning "stomach," and enteron, meaning "small intestine." So the word "gastroenteritis" means "inflammation of the stomach and small intestine." Medically, gastroenteritis is defined as a diarrheal disease, in other words, an increase in bowel movement frequency with or without vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain. An increase in bowel movement frequency is defined by three or more watery or loose bowel movements in 24 hours or at least 200 grams of stool per day. It is classified in many ways, but according to the duration of symptoms, it is described as acute, persistent, chronic, or recurrent.

- Acute: 14 days or fewer than 14 days in duration.

- Persistent: More than 14 but fewer than 30 days in duration.

- Chronic: More than 30 days in duration.

- Recurrent: Diarrhea that recurs after 7 days without diarrhea.[1]

Etiology

Causes of gastroenteritis include bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic, but this article will focus on bacterial causes. Causes of infectious diarrhea vary among different geographical regions, urban to rural areas, and depend on co-morbidities and host immune status. However, the most common cause of acute infectious diarrhea are viruses (norovirus, rotavirus, adenovirus, and others). This is indicated by the observation that stool cultures are positive in less than 5% of cases in most studies. Other than norovirus, important causes of watery diarrhea include Clostridium perfringens, and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Bacterial causes are more responsible for severe cases of infectious diarrhea than other infectious etiologies. For example, a single study found that in otherwise healthy adults with diagnosed severe diarrheal illness, defined as greater than or equal to four watery/loose stools per day for 3 or more days, a bacterial pathogen was identified in 87% of cases. Among these severe bacterial causes, nontyphoidal Salmonella and Campylobacter spp are the most common causes in the United States. The incidence rate per 100,000 persons in 2016 was estimated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention controlled active surveillance program, FoodNet, survey with results as follows:

- Salmonella - 15.4

- Campylobacter - 11.8

- Shigella - 4.6

- Shiga toxin-producing E. coli - 2.8

- Vibrio - 0.45

- Yersinia - 0.42

- Listeria - 0.26[2]

Epidemiology

Acute infectious diarrhea is a very common disease worldwide, even in a developed country like the United States. It is among the leading causes of illness globally and associated with 1.5 to 2.5 million deaths per year. In children younger than 5 years, diarrheal disease is the second most common cause of death by infectious diseases. Worldwide, it affects more than 3 to 5 billion children each year. In the United States, there are more than 350 million cases of acute gastroenteritis annually, and among these, food-borne bacteria are the cause of 48 million cases. It accounts for 1.5 million visits to primary care doctors each year and approximately 200,000 hospital admissions of children under 5 years of age. In the United States, it rarely causes death, but it is still responsible for 300 deaths per year. In general, developed countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada have lower hospital admissions rates in comparison to developing countries. Traveler's diarrhea affects more than 50% of people traveling from developed to developing countries. In the United States, children under 5 years of age are admitted to the hospital in 9 out of 1000 cases per year. In the United Kingdom and Australia, the admission rate is around 12 per 1000 annually. Additionally, the prevalence of Clostridium difficile is also increasing in adults and children.[3]

Pathophysiology

The gut bacteria cause diarrhea by different mechanisms including adherence, mucosal invasion, and toxin production. Knowledge of pathophysiology and the mechanism of these pathogenic strategies also help in the evaluation and management of the disease. One of the main functions of the small intestine is to absorb fluids. With the disorder of the small intestine, the fluid does not get absorbed properly, and the action of different toxins causes the intestinal lining to start excreting fluid which results in relatively loose or watery stools.

Inoculum size is one of the important virulence factors that cause pathology. For Shigella and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), at a minimum of 10–100 bacteria can cause infection, while one hundred thousand or one million of Vibrio cholerae bacteria are required to cause infection. For this reason, infective doses of different pathogens differ in a great range and depend on the host as well as bacteria.

Adherence is another virulence factor for enteric pathogens. Some bacteria need to adhere themselves to the mucosal lining of the gastrointestinal tract initially. They produce various adhesins and other cell-surface proteins which help them to attach to intestinal cells. V. cholerae, for example, adheres to the brush border of small-intestinal enterocytes via specific surface adhesins, including the toxin-coregulated pilus and other accessory colonization factors. Enterotoxigenic E. coli, which causes watery diarrhea, produces an adherence protein called colonization factor antigen. This is necessary for colonization of the upper small intestine by the organism before the production of enterotoxin, causing disease.

Both cytotoxin production and bacterial invasion and destruction of intestinal mucosal cells can cause dysentery. Shigella and enteroinvasive E. coli infections are characterized by the organisms’ invasion of mucosal epithelial cells, intraepithelial multiplication, and subsequent spread to adjacent cells.

Toxin production is another important virulence factor. These toxins include enterotoxins, which cause watery diarrhea by acting directly on secretory mechanisms in the intestinal mucosa, and cytotoxins, which destroy mucosal cells and associated inflammatory diarrhea.[4]

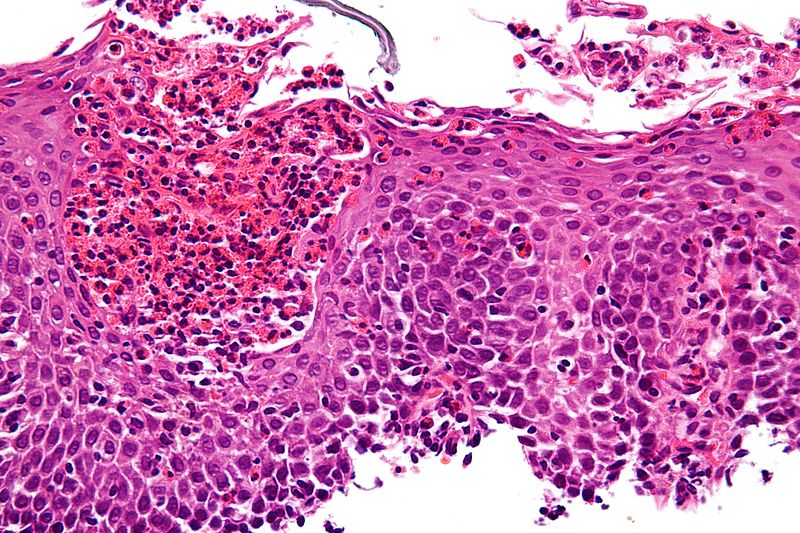

Histopathology

GI infectious diseases can cause mucosal inflammation which represents various patterns of tissue response. Histologic patterns of GI infections can be classified as follows:

- Infections producing minimal or no histologic changes (e.g., Vibrio species)

- Infections producing nonspecific inflammation (e.g., Campylobacter jejuni)

- Infections with suggestive/diagnostic features (e.g., pseudomembranes, etc.)

Campylobacter jejuni, Shigella spp, Salmonella spp, Yersinia and E. coli and few other pathogens all have resembling histopathology. The histopathological picture shows a thick layer of mucosa and cluster of bacteria plus neutrophils in the intraepithelial surface; neutrophils accumulate in the lumen and the basal part of the intestinal crypts as well.[5]

History and Physical

The most common history findings for a patient with gastroenteritis are as follows:

- Nausea

- Diarrhea (watery or bloody in dysentery)

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Fever (suggests an invasive organism as the cause)

On physical examination, the abdomen would be soft, but there may be voluntary guarding. Palpation may elicit mild to moderate tenderness. Fever suggests the cause is invasive pathogens. Signs of dehydration are the most important thing to look for while performing the physical examination; some cases may be alarming and help to identify that which patient needs hospitalization. The following are red flags:

- Dry mucous membranes (dry mouth)

- Decreased skin turgor

- Altered mental status

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension, orthostasis

- Bloody stools

- Recent hospitalization or antibiotics

- Age greater than 65 years

- Comorbidities such as HIV and diabetes[6]

Evaluation

Initial evaluation requires good history taking and physical exam, particularly food and medical history, an assessment of duration, frequency, current volume status, and any other alarming signs and symptoms of the patient. Many cases of acute bacterial gastroenteritis may not require any testing to determine a specific etiology, but in a case of severe volume depletion, a serum electrolyte panel should be indicated to check for any electrolyte derangements. A complete blood count cannot distinguish between bacterial etiologies but helps in suggesting severe disease or potential complications, for example, a high white blood count indicates invasive bacteria or pseudomembranous colitis and low platelets counts indicate the development of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Blood culture should be obtained in a patient with high fever or other severe constitutional symptoms.

Stool testing for bacterial pathogens is indicated in the presence of severe illness (e.g., signs of dehydration/hypovolemia, severe abdominal pain, or need for hospitalization) high-risk host features (e.g., pregnant women, age greater than 70 years, immunocompromised state, or other co-morbidities), and other signs and symptoms of inflammatory diarrhea (e.g., mucus or blood in diarrhea, high-grade fever). A routine stool culture can identify three common bacteria: Salmonella, Campylobacter, and Shigella. Suspicion of other bacterial pathogens (e.g., Vibrio, Yersinia, Aeromonas, and Listeria) should warrant specific microbiology and culture analysis. In case of bloody diarrhea, additional testing for Shiga toxin and leukocytes in stool for EHEC should be ordered in addition to stool culture. In case of persistent diarrhea, the practitioner should send stool samples for ova and parasite testing.[7]

Treatment / Management

The majority of cases of noninflammatory diarrhea are self-limited.

- Supportive management: It is indicated and may include rehydration preferably through the oral route. If oral rehydration is unsuccessful or impossible, then intravenous rehydration should be initiated.

- Antibiotic therapy: Not every patient, even with a known bacterial etiology, should be given antibiotic therapy, especially with Shiga toxin-producing E. coli. Empiric antibiotic therapy with azithromycin or fluoroquinolones can be indicated in severe illness (e.g., greater than 6 stools in a day, fever, need for hospitalization), specific host factors (e.g., age greater than 70 years, immunocompromised host, having co-morbidities), and features suggesting of the invasive organisms (e.g., blood or mucus in stool) but should be discontinued if EHEC is isolated. Tetracyclines have the greatest efficacy for Vibrio. For pregnant patients with the suspicion of Listeria, ampicillin is the drug of choice. For C. difficile infection (CDI), discontinuation of the causative antibiotic and antibiotic therapy should be initiated. It should be noted that recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines changed in March 2018 and now recommend either oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin for nonsevere over oral metronidazole for severe CDI. A combination therapy of oral vancomycin with IV metronidazole should be used for fulminant CDI.

- Symptomatic therapy: Loperamide can be given carefully in patients who are afebrile and have non-bloody diarrhea.[8]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of acute bacterial gastroenteritis includes other causes of gastroenteritis such as viral and parasitic gastroenteritis. Common foodborne illnesses also should be considered in differentials. Other diseases that can cause watery diarrhea are Crohn disease, pseudomembranous colitis, microscopic colitis, acute HIV infection, irritable bowel disease, and lactose intolerance. Bloody diarrheal disease other than dysentery includes ulcerative colitis. Celiac disease and malabsorption syndromes also cause diarrhea.[9]

Complications

Dehydration and depletion of electrolytes are the most common complications above all. Other complications that are common after acute gastroenteritis are the transformation of acute into chronic diarrhea which can lead to lactose intolerance or small-bowel bacterial overgrowth. Some other post-diarrhea complications include exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease, septicemia, enteric fever, and Guillain-Barre syndrome, a complication likely after Campylobacter infection. Reactive arthritis may occur, particularly after Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, or Yersinia.[10]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of bacterial gastroenteritis is best done with an interprofessional team that includes the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, infectious disease consult and the emergency department physician. The key aim of treatment is to prevent dehydration and electrolyte alterations. The majority can be treated as outpatients but children and the elderly may require admission, depending on their hydration status. Some other post-diarrhea complications include exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease, septicemia, enteric fever, and Guillain-Barre syndrome, a complication likely after Campylobacter infection. Reactive arthritis may occur, particularly after Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, or Yersinia.[10] With proper treatment the outcomes are excellent but any delay in treatment can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. [11][12]