Introduction

The anal triangle is the posterior half of the perineum, by definition. The perineum can be found between the thighs and below the pelvic diaphragm. The perineum is comprised of the anal and urogenital triangles. A theoretical line connecting the two ischial tuberosities of the pelvis divides the perineum into the posterior anal triangle and anterior urogenital triangle.

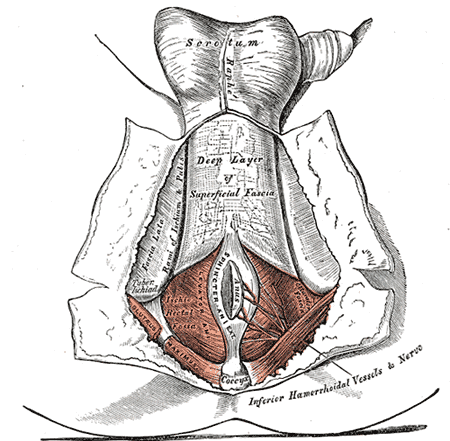

The anal triangle is formed by the coccyx, sacrotuberous ligaments, and an imaginary line between the ischial tuberosities. The anal triangle contains the anal canal and two ischiorectal (ischioanal) fossae that lie on either side of the anal canal.

Boundaries of the anal triangle:

- Anterior: posterior margin of the perineal membrane

- Posterior: coccyx

- Posterolateral: sacrotuberous ligaments

- Superior: levator ani muscle

Structure and Function

As stated above, the anal triangle contains the anal canal and two ischiorectal fossae.

Anal Canal

The anal canal is the hindmost part of the gastrointestinal system.[1] There is both an anatomic and surgical definition of the anal canal. The anatomic anal canal spans from the anal verge to the pectinate (dentate) line. The surgical anal canal is longer and spans from the anal verge to the anorectal line.[2] The anal verge is the junction of anoderm with perianal skin.

The anal canal divides into the upper two-thirds and lower one-third by the pectinate line. Simple columnar epithelium is present above the pectinate line, and the stratified squamous epithelium appears below it.[3] The anal canal contains anal columns (columns of Morgagni) and anal valves, which are the inferior end of the anal columns. Above the anal valves are the anal sinuses which contain anal glands that secrete mucus into the anal canal.[1]

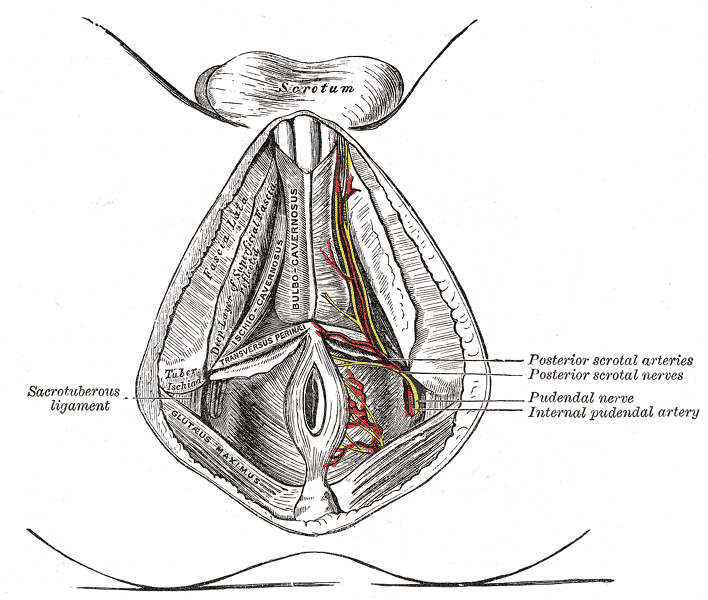

Ischiorectal Fossae

The ischiorectal fossae contain the inferior rectal vessels and nerve and ischioanal fat, which supports the anal canal and allows for the anal canal to expand during defecation. The pudendal (Alcock’s) canals lie on the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossae and contain the pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels.[1]

Boundaries of the ischiorectal fossae[4]:

- Anterior- sphincter urethrae and deep transverse perineal muscles

- Posterior- gluteus maximus muscle and sacrotuberous ligament

- Superomedial- external anal sphincter and levator ani muscle

- Lateral- fascia covering the obturator internus muscle

- Floor- skin

Embryology

Above the pectinate line, the anal canal derives from the cloaca, which has an endodermal lining. Below the pectinate line, the anal canal forms from the proctodeum and is of ectodermal origin. Therefore, the pectinate line is the fusion between endoderm and ectoderm.[2]

The fusion of the proctodeal ectoderm with cloacal endoderm forms the cloacal membrane. The urorectal septum separates the cloaca into the ventral bladder and urogenital sinus and dorsal rectum and anal canal. The urorectal septum joins the cloacal membrane. Then, the cloacal membrane divides into an anal membrane and urogenital membrane.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pectinate line is an important anatomic landmark, as it is where the blood supply, lymphatics, and nerves differ based on being above or below the pectinate line.

Above the pectinate line, the superior rectal artery is responsible for blood supply. It is a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. Venous drainage above the pectinate line drains to the portal venous system, which is critical to differentiate from below the pectinate line. The internal hemorrhoidal plexus drains to the superior rectal vein. This blood continues to drain through the inferior mesenteric vein, splenic vein, and then to the portal vein.[6] Lymphatic drainage of the anal canal above the pectinate line is to the internal iliac lymph nodes.[7]

Below the pectinate line, the inferior rectal arteries and veins supply and drain the muscles and skin around the anus. The inferior rectal vessels are branches from the internal pudendal vessels. Blood from this area below the pectinate line ultimately drains to the caval venous system. Blood from the external hemorrhoidal plexus drains into the inferior rectal vein. The blood continues to drain to the internal pudendal vein, internal iliac vein, common iliac vein, and lastly, to the inferior vena cava.[6] Lymphatic drainage of the perineum below the pectinate line is to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.[7]

Nerves

The internal anal sphincter and the anal canal above the pectinate line receive visceral innervation from sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. The sympathetic fibers are from the inferior pelvic plexus, and the parasympathetic fibers are from the inferior pelvic plexus and pelvis splanchnic nerves.[1][2]

Below the pectinate line, the anal canal has somatic innervation from the inferior rectal nerve. The inferior rectal nerve is one of the branches of the pudendal nerve. The inferior rectal nerve innervates the external anal sphincter and is responsible for sensation to the anal canal that ranges up to 15 mm above the pectinate line; this includes the sensations of pain, touch, and temperature.[1]

Muscles

- The obturator internus muscle is the lateral border of the ischiorectal fossae.

- The levator ani is the superior boundary of the anal triangle. It functions to support and raise the pelvic floor. Levator ani consists of the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and iliococcygeus muscles.[1][4]

- The coccygeus muscle also supports and raises the pelvic floor.

- The internal anal sphincter is comprised of involuntary smooth muscle. It is a continuation of the circular muscle of the rectum.[1] It is under the control of the autonomic nervous system and is in a state of constant contraction which relaxes during defecation. The internal anal sphincter is responsible for the majority of anal continence.

- The longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum combines with some fibers of the levator ani muscle to form the conjoined longitudinal muscle.[2] It is between the internal and external anal sphincters.

- The external anal sphincter consists of voluntary skeletal muscle. It divides into three parts: subcutaneous, superficial, and deep.[3] It functions to close the anus.

Surgical Considerations

Hemorrhoids

If internal and external hemorrhoids are not treatable with conservative management, surgical intervention may be necessary. Surgical approaches are reserved for patients with acute complicated hemorrhoids or if non-operative treatments have failed. Surgical treatment options include hemorrhoidectomy, plication, doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation, and stapled hemorrhoidopexy.[6][8]

Anal Cancer

The treatment of choice for cancer of the anal canal is concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Surgery is a consideration when there is recurrent or persistent tumor after chemoradiotherapy or if the tumor is a stage T1 with no sphincter involvement.[7][9]

Perirectal Abscess

Perianal abscesses are one type of perirectal abscess. Perirectal abscesses also include ischiorectal abscesses, intersphincteric abscesses, and supralevator abscesses. The abscesses form when there are occlusion and infection of an anal crypt gland. Physical exam findings can reveal a small fluctuant mass with erythema and induration of the overlying skin. Patients present with symptoms of perirectal pain and fever. Perirectal abscesses are treated surgically with incision and drainage.[10][11]

Clinical Significance

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids arise from the internal or external hemorrhoidal plexuses and result from dilation and irritation of the anal cushions. Risk factors include constipation, diarrhea, prolonged straining to defecate, and pregnancy. Internal hemorrhoids typically present as painless bleeding with defecation. Internal hemorrhoids arise above the pectinate line and are usually painless because this area's nerve supply is by visceral innervation. External hemorrhoids can be pruritic and also present with bleeding. External hemorrhoids occur below the pectinate line. Thrombosis of external hemorrhoids is painful because this area below the pectinate line has somatic innervation. Hemorrhoids preferably receive conservative management, including eating a high fiber diet, doing sitz baths, and using stool softeners, etc. There are also medications and other non-operative treatment options available, such as rubber band ligation, before resorting to surgery as treatment.[6][8]

Anal Cancer

Most cancers of the anal canal are classified as squamous cell carcinoma and share a strong correlation with a human papillomavirus infection of the anus. Cancer of the anal canal can present similarly to benign anal disease with symptoms such as pain, bleeding, pruritus, and a mass. Diagnosis includes a biopsy, pelvic MRI, and PET/CT. Anal cancer is treated with concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy and has a very high success rate.[7][9]