Continuing Education Activity

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, characterized by recurrent episodes of airflow obstruction resulting from edema, bronchospasm, and increased mucus production. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of pediatric asthma and highlights the role of the healthcare team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of asthma.

Review the appropriate evaluation of asthma.

Outline the treatment and management options available for asthma.

Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance asthma care and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, characterized by recurrent episodes of airflow obstruction resulting from edema, bronchospasm, and increased mucus production. Commonly associated with seasonal allergies (allergic rhinitis) and eczema (atopic dermatitis), these three conditions form what is known as the atopic triad.

Patients who have asthma may experience a range of respiratory symptoms, such as wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, and chest tightness. There is a wide range in the frequency and severity of the symptoms, but uncontrolled asthma and acute exacerbations can lead to respiratory failure and death.[1]

Etiology

The exact etiology of asthma remains unclear and appears to be multifactorial. Both genetic and environmental factors seem to contribute. Positive family history is a risk factor for asthma but is neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of the disease. Multiple environmental exposures, both prenatal and during childhood, are associated with the development of asthma.

One of the most well-studied risk factors during the prenatal period is maternal smoking, which does appear to increase the risk of wheezing in childhood and likely increases risk for the development of asthma. Other proposed prenatal risk factors include maternal diet and nutrition, stress, use of antibiotics, and delivery via Cesarean section, though studies regarding these have been less conclusive.

Many childhood exposures have also been the target of research. Tobacco smoke exposure appears to increase the risk of development of asthma and is also a known trigger for exacerbations in those already diagnosed with the disease. Other risk factors include animal, mite, mold, or other allergens, as well as air pollutants.

The role of many other proposed risk factors remains unclear, and studies are often inconclusive or contradictory. The influence of breastfeeding and avoidance of nutritional allergens during breastfeeding is controversial. Family size and structure have been proposed as a risk factor; an increase in family size may be protective, though birth order seems less likely to be contributory. Low socioeconomic status has correlations with increased morbidity, though the increased prevalence is a topic of debate. Viral lower respiratory infections and the use of antibiotics have been associated with early childhood wheezing, but their role in causing persistent asthma is less clear. There has been a particular association with Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and asthma, but not causation. Viral respiratory tract infections are known to trigger existent asthma.[2][3]

Epidemiology

There are an estimated 300 million people who have asthma worldwide, with a significant geographic variation of prevalence, severity, and mortality. According to the CDC, 8.4% (or over 6 million) of children in the United States have asthma. Asthma is a chronic disease that has a high morbidity rate and a comparatively low mortality rate overall. It is the leading cause of chronic disease and missed school days in children. While asthma classically begins during childhood, and the incidence and prevalence are higher during this period, it can occur at any time throughout life. Before puberty, the rate of asthma incidence, prevalence, and hospitalizations is higher in boys than girls, though this reverses during adolescence. Severe asthma affects 5% to 15% of this population in the U.S. and world, with males being more likely to have severe asthma in childhood (66%) and adolescence (57%). Studies have shown an increased in prevalence, rate of emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and mortality in African American and Hispanic populations in the United States.[2][3][4][5]

Pathophysiology

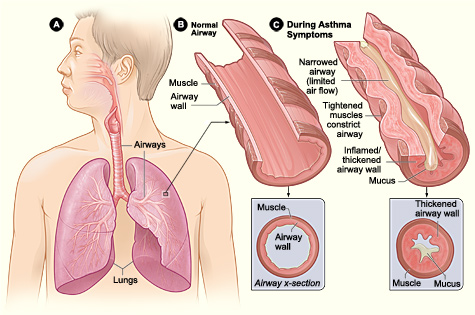

The pathophysiology of asthma involves the infiltration of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes into the airway, activation of mast cells, and damage to the epithelial cells. These inflammatory responses lead to the classic features of airway swelling, increased mucus production, and bronchial muscle dysfunction, which produce airway flow limitation and asthma symptoms. Remodeling, a term used to describe persistent changes in the airway structure, can occur, ultimately leading to fibrosis, mucus hypersecretion, epithelial cell injury, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and angiogenesis.[6][7][8][9]

History and Physical

Classic symptoms of asthma include cough, wheezing, chest tightness, and shortness of breath. Symptoms are often episodic and can become triggered by numerous factors, including upper respiratory tract infections, exercise, exposure to allergens, and airway irritants such as tobacco smoke. They may also be worse at night.

As previously discussed, there exists a classic triad of asthma, eczema, and allergies, and it is worthwhile to elicit a personal or family history of these components as young children may not have a formal diagnosis. In children, the diagnosis of RAD (reactive airway disease) or recurrent WARIs (wheezing associated respiratory infections) often precede a formal diagnosis of asthma.

During acute exacerbations, children may also have significantly increased work of breathing or audible wheezing, which may be appreciated by caregivers and prompt presentation for further evaluation. Information to ascertain during these acute visits include:

- What interventions have taken place before arrival, e.g., nebulizer treatments or rescue inhaler use

- If the child has been taking other asthma medications as prescribed,

- If the child has ever been hospitalized for asthma

- If critical care admission was required

- If the child has ever needed intubation

- If the child has taken oral steroids for asthma exacerbations and if so, when

Physical Examination

The physical examination should focus on three main areas, which will help to develop your differential diagnosis and identify co-morbid conditions. These are general appearance, including state of nutrition and body habitus, signs of allergic disease, and signs of respiratory dysfunction.

The physical examination may be completely normal, especially in a child with well-controlled asthma who does not have an acute exacerbation. Children may have increased nasal secretion, mucosal swelling, or nasal polyps, consistent with allergic rhinitis. The skin exam may reveal atopic dermatitis.

Cough, prolonged expiratory phase, and wheezing, which may be expiratory or inspiratory, are common respiratory exam findings in asthmatic children with acute exacerbation. Children may experience varying degrees of tachypnea and dyspnea. There may also be signs of increased work of breathing (“belly breathing,” use of accessory muscles, including subcostal, intercostal, or supraclavicular retractions, nasal flaring), tripod positioning, inability to speak in full sentences, or grunting. Of note, a child who was previously noted to have significantly increased work of breathing by caregivers, but who has now “tired out,” appears to be breathing at a normal rate, or who becomes lethargic, may have impending respiratory failure.

In a child with significant airway obstruction, there may come a point at which wheezing may no longer be present. This absence of wheezing indicates that the child is moving a minimal volume of air. A child who develops altered mental status, appears truly lethargic, becomes unresponsive, is cyanotic, or has a “silent chest” has signs of impending respiratory failure and may rapidly decompensate to respiratory arrest.

Features such as digital clubbing, barrel chest, localized wheezing, urticarial rash, or stridor may suggest other diagnoses or comorbid conditions.[10][9]

Evaluation

In children who have asthma or in whom asthma is suspected, a full history and physical exam should be performed, with a focus on the components discussed above.

Making the Diagnosis of Asthma

A diagnosis of asthma should be a consideration when any of the following indicators are present:

- Recurrent episodes of cough, wheezing, difficulty breathing, or chest tightness

- Symptoms that occur at night or disrupt sleep

- Symptoms that appear to be triggered by upper respiratory tract infections, exercise, exposure to animals, dust, mold, tobacco smoke, aerosols, changes in weather, stress, strong emotional expression, or menses

In children who are at least five years of age and adults, pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry can help confirm the diagnosis.

Baseline spirometry provides the following information FVC (Forced vital capacity), FEV1 ( forced expiratory volume at 1 second), FEV1/FVC, and F25-75 (the difference between the forced expiratory volume at 25% and 75%). Assessment of the bronchodilator response begins with the baseline spirometry followed by the administration of a short-acting bronchodilator (most commonly, albuterol 2 to 4 puffs in adults and older children). According to the ATS/ERS guidelines, reversibility is deemed significant when there is a greater than 12 % improvement from baseline or an increase of over 200 ml in FEV1.

Peak flow meters are for monitoring asthma. A decline of 20 to 30% or more from the patient's personal best may be indicative of an impending or current exacerbation. A peak flow of less than 40% of their best is indicative of severe exacerbation.

Provocation Testing

Further testing may be indicated in patients with a high pretest probability of asthma, meaning the patient displays typical symptoms like coughing, wheezing, or dyspnea, but normal spirometry testing and equivocal or no response to bronchodilators.

Exercise Testing

- Exercise-induced asthma may be diagnosed via exercise testing. The patient is monitored on a treadmill and has serial spirometry performed. The test is positive if there is a reduction in FEV1 greater than 15% from baseline.

Methacholine Challenge

- Methacholine is a drug that acts on acetylcholine receptors and causes transient narrowing of airways by inducing bronchoconstriction. The test is positive if there is a reduction in FEV1 greater than 20% from baseline. A normal test is adequate to rule out asthma, though the methacholine challenge may be falsely positive.[11][12][13]

Allergy Testing

- Inhalant allergens, likey molds, pollens, dander, and dust mites, are common triggers in patients with asthma. Allergy testing should be administered in patients with persistent asthma, though it may be considered in those with intermittent asthma. Microarray testing for IgE can further elucidate allergy triggers.[14]

Acute Exacerbation

Children who present for an acute exacerbation should have a full set of vitals collected. Overall clinical appearance should determine whether they should escalate to a higher level of care. Asthma exacerbations are diagnosed clinically and do not require laboratory or imaging studies routinely; it is appropriate to begin treatment.

It is appropriate to consider a chest X-ray in the following setting:

- First wheezing episode

- Asymmetric lung findings

- Unexplained fever

- Symptoms continue to worsen despite treatment

- The patient is critically ill

A chest x-ray may reveal hyperinflated lungs and interstitial prominence. If there is any focal consolidation, the patient should also receive treatment for pneumonia.

Other laboratory studies, including ABG, may also be considered in patients if symptoms continue to worsen despite treatment or the patient is critically ill; however, initial therapy with nebulizers should not be delayed.[15]

Treatment / Management

Non-pharmacologic Management

Avoiding exposure to environmental factors that may provoke asthma personal or second-hand tobacco smoke, food or drug triggers, and pollutants and irritants is vital.[16] Vitamin D deficiency has been noted to be highly prevalent in patients with atopic disease. There has been evidence that vitamin D deficiency is contributory to the disruption of the immune system and the worsening of reactive airways. Increased screening and appropriate supplementation may lead to an improvement in atopic disease, including asthma.[17]

STEP Therapy for Asthma

The following discussion will highlight the step therapy proposed by EPR-3.

The preferred treatment option for intermittent asthma, as well as for quick relief of asthma symptoms and the prevention of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction is a short-acting beta-2 agonist. This is referred to as STEP 1. Albuterol and levalbuterol are examples of short-acting bronchodilators. They have a quick onset of action, within 5 to 15 minutes, and a duration of action of 4 to 6 hours. Their administration is most often by nebulizer or inhaler.

STEPS 2-6 refer to options for persistent asthma. In each of these steps, inhaled corticosteroids are a component of the preferred treatment regimen.

The preferred treatment for step 2 is a low-dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). Montelukast can be an alternative. Montelukast is a leukotriene receptor antagonist available in 4 mg granules, or 4 mg and 5 mg chewable tablets, as well as in a 10 mg tablet formulation. Single evening dosing prescribing is by age and FDA approved for asthma control from 12 months of age.

The preferred option for step 3 is a medium dose ICS in the 0 to 4-year-old children. In the 5 to 11 year age group, the preferred option is either a medium-dose ICS or a combination ICS + long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA). For those ages 12 years through adulthood, the preferred choice is a low dose of ICS + LABA or medium-dose ICS. There was a black-box warning on LABAs due to concerns about increasing deaths in patients taking LABAs; however, according to more recent studies, LABAs demonstrated safety when combined with inhaled corticosteroids. LABA monotherapy is indeed associated with an increase in asthma-related mortality and serious adverse events.

Step 4 in the 0 to 4-year-old age range is a medium dose ICS + either a LABA or montelukast. In ages, 5 to 11 years and 12 and above, a medium dose ICS + LABA is the preferred option.

Step 5 for 0-4 years is high dose ICS + either LABA or montelukast; in 5-11 years and 12 and above, a high dose ICS + LABA. EPR-3 also recommends consideration of omalizumab for ages 12 and above. Since the publication of these guidelines, Omalizumab has received FDA approval for ages 6 years and above. Omalizumab is a monoclonal antibody indicated for moderate to severe persistent asthma with objective evidence of perennial aeroallergen sensitivity and inadequate control with ICS.

Step 6 for ages 0-4 years is a high dose ICS + either LABA or montelukast or oral corticosteroids; for ages 5-11 years – high dose ICS + LABA + oral systemic corticosteroid; and for ages 12 and up, high dose ICS + LABA + oral corticosteroid are preferred. Omalizumab may be a consideration for appropriate patients with allergy.

Theophylline is a medication that may be an alternative medication in Steps 2 through 6. However, its use requires caution due to its narrow therapeutic range and potential side effects, including diuresis, tremors, and headaches.[18]

Asthma action plans are recommended for all patients with asthma. These are individualized to and developed in partnership with each patient. They include detailed directions on how to manage asthma with instructions for when the patient is well, beginning to feel symptoms, and in an acute exacerbation that necessitates medical evaluation.[19]

Management of Acute Exacerbations

Initial management of a child who presents to the emergency department with an acute asthma exacerbation includes bronchodilators and steroids.

Albuterol:

2.5 - 5 mg of nebulized albuterol should be given as initial management and can be re-dosed every 20 minutes. If the child is 5 years or older, 5 mg is the recommended dose. If a child is experiencing significant respiratory distress and is declining between doses, it may be re-dosed more frequently, or continuous nebulization of albuterol may be required.

Ipratropium:

Dosing of 250 to 500 mcg of ipratropium should be co-administered with albuterol for three doses in moderate to severe exacerbations.[20]

Corticosteroids:

Oral and IV steroids have been demonstrated to have equivalent potency in treating acute asthma exacerbations. Patients should be given prednisolone PO or methylprednisolone IV 1 to 2 mg/kg/day or dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg PO or IV depending on their level of respiratory distress and ability to swallow. Dexamethasone has been shown non-inferior to a short course of prednisone or prednisolone for an acute exacerbation.[21]

Magnesium sulfate:

If the child continues to experience respiratory distress, they should receive magnesium sulfate at a dose of 50 mg/kg (up to 2 to 4 g) over 15 to 30 minutes.

In exacerbations that are refractory to the above, epinephrine (1 per 1000 concentration) at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg or terbutaline at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg, should be considered. These also have beta-agonist properties and thus promote bronchodilation.

Supplemental oxygen can be applied to maintain oxygen saturation above 90 to 92%, and heliox can be considered to aid in delivering oxygen to lower airways. If patients have been treated with all of the above and still are experiencing respiratory distress, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation should commence as it may alleviate muscle fatigue and assist in maximizing inspiration.

Intubation should be avoided in the asthmatic patient as there are several associated risks. Intubation may aggravate bronchospasm, induce laryngospasm, and increase the risk of barotrauma. Ketamine (at a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg) is the preferred induction agent due to bronchodilator effects; it is also unlikely to cause hypotension. If intubated, asthmatic patients may require deep sedation or paralysis. On the ventilator, the I to E ratio should be 1:3 to allow for adequate expiratory time, tidal volume goal of 6-8 cc/kg, plateau pressure goal should be 30 or less, and PEEP of 5 or greater. Lung protective settings minimize alveolar collapse while reducing the risk of barotrauma.[16][22]

About the Devices

Metered-dose inhalers

- Delivers the drug directly to the airway, though there is a significant amount (up to 90%) that is deposited in the oropharynx even if used correctly

- Should be inhaled shortly after initiating a slow, full inspiration and breath should be held for 10 seconds at full inflation

- Can be challenging to use in children less than 5 and in those with acute exacerbation

- Coordination of firing the inhaler and timing the inspiration becomes less important if using a spacer device. Some literature argues for the use of a spacer in all patients.

Nebulizers

- Useful in young children and those in acute exacerbation

- Allows for delivery of a higher dose to the airways, though only about 12% actually reaches the lungs

- Similar efficacy to inhalers when the inhalers are used correctly, though may patients have more confidence in the nebulizer as it is something they are continuously watching

Oral Medications

- Tablets and syrups bypass the requirement for coordinating inhalation and may bypass obstructed airways, though they may have systemic effects.

Injected medications

- Subcutaneous or intramuscular injections merit consideration in acute exacerbations in patients who are in acute exacerbations and are very ill

- Injectable medications include epinephrine and terbutaline, though they have systemic effects.[23]

When to refer to Pediatric Pulmonology

Referral to a pulmonologist is necessary for patients who display signs of severe disease or have other complicating conditions. A patient should be referred for pulmonology care if he or she has had a life-threatening exacerbation or exacerbation requiring hospitalization, is not meeting goals of therapy after 3 to 6 months, is being considered for immunotherapy, requires step 4 or higher care (though in children 0 to 4, Step 2 or higher may be considered for referral), or has needed more than 2 bursts of oral steroids in a year. A child who has co-morbidities that complicate the diagnosis or the condition, in whom specialized testing is necessary, or in whom there is a complex psycho-social environment with sub-optimal compliance or exposure to provoking factors should also be considered for referral.[24]

Differential Diagnosis

Upper Airway Diseases

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis

Large Airway Obstruction

- Foreign body aspiration

- Vascular ring or laryngeal webs

- Laryngomalacia

- Tracheomalacia

- Lymphadenopathy

- Mass

- Epiglottitis

- Vocal cord dysfunction

Small Airway Obstruction

- Asthma

- Bronchiolitis/wheezing-associated respiratory infections

- Cystic fibrosis

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Cardiac disease

Other Causes

- Congestive heart failure

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Anaphylaxis

- Angioedema

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(more likely in adults)

- Pulmonary embolism (more likely in adults)[25]

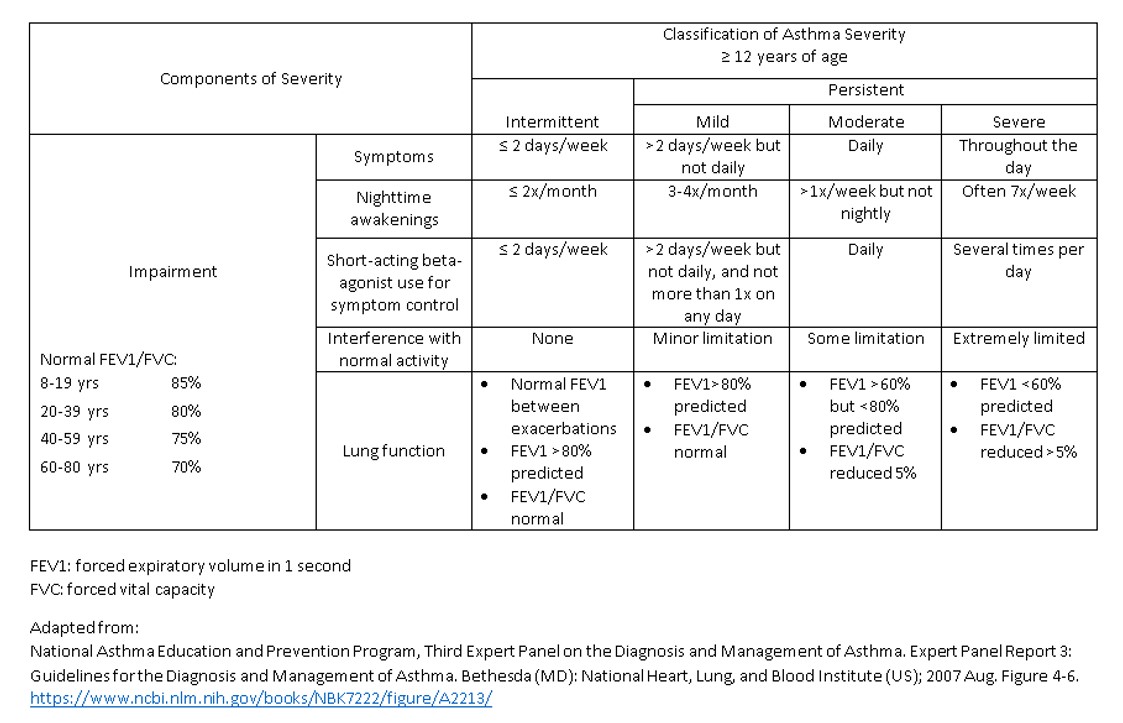

Staging

Classifying Asthma Severity and Control

Asthma is classified based on two domains: severity and control. Each has two components: impairment and risk.

Severity is assigned when the patient is first seen and before treatment. The number of subgroups within impairment will increase as the reference age group increases.

Impairment

Assessment of impairment includes the following for each age group:

Ages 0 to 4:

- Daytime symptoms, nighttime awakenings, use of short-acting B agonists and activity

Ages 5 to 11:

- Daytime symptoms, nighttime awakenings, use of short-acting B agonists and activity

- Lung function measures

Ages 12 and above:

- Daytime symptoms, nighttime awakenings, use of short-acting B agonists and activity

- Lung function measures

- Quality of life measures

- Three quality of life questionnaires appear within the EPR - 3 documents: The Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire (ATAQ), the Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), and the Asthma Control Test (ACT).

Control assessment is necessary on all subsequent visits. Asthma severity falls into one of four groups: intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent. Asthma control can classify as well-controlled, not well-controlled, and very poorly controlled. Increased morbidity, cost, and mortality are associated with poor asthma control.

Risk refers to the number of systemic steroid bursts in the 0 to 4-year group, while in those 5 to 11 years and over 12 years through adulthood, adverse effects from medication and deterioration in lung function are also included.

The goals of therapy require development in partnership with patients.

Treatment goals include reduced or absent asthma symptoms, normal or near-normal lung function, normal activities, and sleep and minor or absent side effects from medications.

Treatment of asthma requires a multi-pronged approach - considering comorbid conditions such as allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux, etc. Patients should receive knowledge and skills training to facilitate their participation in asthma self-management.

Monitoring Asthma

At each visit, consider[26]:

- Asthma signs and symptoms

- Lung function

- Quality of life assessment

- Exacerbation history

- Pharmacotherapy – medications and side effects

- Patient-provider communication and patient satisfaction

Prognosis

Although asthma is not curable, it is controllable with proper management. Asthma will commonly start before school age in children. Early childhood asthma and severe asthma increased the risk of chronic obstructive symptoms. While many patients require long-term medical follow up and medications, asthma remains a treatable disease, and some patients do experience significant improvement or resolution of symptoms with age.[26]

Complications

Asthma can severely limit the ability to engage in normal daily activities, including sports and outdoor activities. While asthma is a treatable disease, some of those treatments have side effects. For example, inhalers may cause hoarse voice, and inhaled corticosteroids may increase the risk for fungal infections. Oral steroids increase the chance of developing Cushing syndrome, including weight gain and metabolic dysfunction. However, poorly controlled asthma can lead to airway remodeling and chronic obstruction, increase the risk of obstructive sleep apnea, pneumonia, or gastroesophageal reflux.[27][15][28]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Engaging patients in their care and providing education regarding the disease process and triggers is crucial to maintaining control of asthma. Behavioral modifications, including weight loss and avoiding exposure to tobacco or environmental allergens, is key. The use of daily and as needed medications can control symptoms and prevent acute exacerbations. Asthma action plans can provide a program that is easy to follow and identifies the need for additional evaluation and treatment.

Pearls and Other Issues

All that wheezes is not asthma, and it is essential to keep a broad differential while bronchiolitis/wheezing associated respiratory infections are the most common alternative diagnosis, many other disease processes present with wheezing.

Be wary of patients with a "normal" blood gas who appear to be experiencing significant respiratory distress and patients who appear lethargic or altered. They may be nearing respiratory failure and respiratory arrest with secondary cardiac arrest.

Patients requiring continuous nebulized treatments or interventions beyond albuterol, ipratropium, and steroids may have status asthmaticus. They require readmission for further evaluation and management.

Remember to look for both common triggers (URIs, allergens, exercise) and uncommon triggers (reflux, medications, psychological distress).

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Asthma is a chronic disease process, which can lead to respiratory failure and death if it is not well controlled. Non-adherence to medication regimens and exposure to triggers can significantly increase the risk of morbidity and mortality. Proper education to both pediatric patients and their families can ensure understanding of the disease and provide an incentive for better control, which is achievable by using an interprofessional approach aimed at education. Nurses and respiratory therapists can help the team by engaging patients in teaching how to use inhalers, avoid triggers, and how to follow asthma action plans. The pharmacist has to review all medications, their appropriate dosing, and check for interactions, as well as educate the patient on the importance of medication compliance. Education and treatment can extend to the school system to assist in the management of asthma. Social workers can ensure that the patient can obtain medications and any equipment necessary to continue treatment. To prevent the high morbidity and mortality of pediatric asthma, close communication between the interprofessional team members is vital.[15][28][26] [Level 5]