Continuing Education Activity

The term "glomerulonephritis" encompasses a subset of renal diseases characterized by immune-mediated damage to the basement membrane, mesangium, or capillary endothelium, leading to hematuria, proteinuria, and azotemia. Acute forms of glomerulonephritis (GN) can result from either a primary renal cause or a secondary illness that causes renal manifestations. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of glomerulonephritis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the etiology of glomerulonephritis.

- Summarize the physical findings associated with glomerulonephritis.

- Outline the management considerations for the different diseases grouped under the term 'glomerulonephritis.'

- Describe interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to improve outcomes for patients affected by glomerulonephritis.

Introduction

The structural and functional unit of the kidney, the 'nephron,' consists of a renal corpuscle (glomerulus surrounded by a Bowman capsule) and a renal tubule. Each kidney in an adult human contains around 1 million nephrons.[1] A fenestrated endothelium forms the inner glomerular layer, followed by a layer composed of various extracellular proteins forming a meshwork called the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). The outer layer has visceral epithelial cells, podocytes, and mesangial cells. The intricate arrangement provides the basis for continuous plasma volume filtration at the glomerular level.

The term "glomerulonephritis" encompasses a subset of renal diseases characterized by immune-mediated damage to the basement membrane, the mesangium, or the capillary endothelium, resulting in hematuria, proteinuria, and azotemia.

Acute forms of glomerulonephritis (GN) can result from either a primary renal cause or a secondary illness that causes renal manifestations. For instance, acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) is a typical example of acute glomerulonephritis secondary to a streptococcal infection; similarly, Staphylococcus aureus infection can also lead to glomerulonephritis. In recent times, however, the incidence of glomerulonephritis associated with staphylococcal has increased as opposed to the reduction of PSGN in the United States and most developed countries.[2][3][4]

Most forms of glomerulonephritis are considered progressive disorders. Without timely therapy, progress to chronic glomerulonephritis (characterized by progressive glomerular damage and tubulointerstitial fibrosis leading to a reduced glomerular filtration rate). This leads to the retention of uremic toxins with subsequent progression into chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) along with their associated cardiovascular diseases.[5]

Etiology

Etiological classification of glomerulonephritis can be made based on clinical presentation, ranging from severe proteinuria (>3.5 g/day) and edema qualifying for the nephrotic syndrome to a nephritic syndrome where hematuria and hypertension are more prominent while proteinuria is less pronounced.

Nephrotic Glomerulonephritis

- Minimal change disease

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Membranous nephropathy

- HIV associated nephropathy

- Diabetic nephropathy

- Amyloidosis[6]

Nephritic Glomerulonephritis

- IgA nephropathy

- Henoch Schonlein purpura (HSP)[7]

- Post streptococcal glomerulonephritis.

- Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Idiopathic crescentic glomerulonephritis

- Goodpasture syndrome

- Lupus nephritis

- Hepatitis C infection[8]

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (typical presentation is with acute nephritic syndrome, however, sometimes features resembling nephrotic syndrome may occur, additionally)[9]

A more modern and widely accepted way to classify glomerulonephritis is to divide it into five forms of glomerulonephritis based on underlying immune processes. The following is the modern classification of glomerulonephritis, including pathogenic type and the disease entity associated with it:

- Immune-complex GN - IgA nephropathy, IgA vasculitis, infection-related GN, lupus nephritis, and fibrillary GN with polyclonal Ig deposits

- Pauci-immune GN - PR3-ANCA GN, MPO-ANCA GN, and ANCA-negative GN

- Anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) GN - Anti-GBM GN

- Monoclonal Ig GN - Proliferative GN with monoclonal Ig deposits, monoclonal Ig deposition disease, fibrillary GN with monoclonal Ig deposits, and immunotactoid glomerulopathy

- C3 glomerulopathy - C3 glomerulonephritis, dense deposit disease[10]

Epidemiology

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a prominent cause of renal impairment. It leads to 10% to 15% of end-stage renal disease cases in the United States. In most instances, the disease becomes progressive without timely intervention, eventually leading to morbidity.[11] This makes chronic glomerulonephritis the third most common cause of end-stage renal disease in the United States, following diabetes mellitus and hypertension, accounting for 10% of patients on dialysis.

Glomerulonephritis constitutes 25% to 30% of all end-stage renal disease cases—about a quarter of patients present with nephritic syndrome. Progression, in most cases, is relatively quick, and end-stage renal disease may ensue within weeks or months of the beginning of acute nephritic syndrome.

IgA nephropathy has been found to be the most common cause of glomerulonephritis worldwide.[12] However, the incidence of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis has declined in most developed countries. As reported by Japanese researchers, the incidence of postinfectious glomerulonephritis in their country climaxed in the 1990s. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which accounted for nearly all cases of postinfectious GN in the 1970s, has reduced to about 40-50% since the 1990s, while the percentage of Staphylococcus aureus–related nephritis rose to 30%, and hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis also increased.[13]

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis remains much more prevalent in regions such as the Caribbean, Africa, India, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, South America, and Malaysia. In Port Harcourt, Nigeria, acute glomerulonephritis in the pediatric age group 3-16 years was 15.5 cases/year, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.1:1; it is not much different currently.[14]

An Ethiopian study from a regional dialysis center found that acute glomerulonephritis was the second most common cause of acute kidney failure requiring dialysis, comprising about 22% of cases.[14] Geographic and seasonal variations in the occurrence of PSGN are more pronounced for pharyngeal-associated GN than in cutaneously-associated disease.[15]

Age-, Gender-, and Race-related Demographics

Acute nephritis can appear at any age, including infancy. Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis usually develops in the pediatric population aged 5-15 years. Only 10% of cases occur in patients 40 years old or above. Outbreaks are common in children around six years old.[15]

Acute glomerulonephritis affects males more than females, with a male-to-female ratio of 2 to 1. Postinfectious glomerulonephritis has no predilection for racial or ethnic groups.

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathogenetic mechanism common to all of these different varieties of glomerulonephritis (GN) is immune-mediated, in which both humoral as well as cell-mediated pathways are active. The consequent inflammatory response, in many cases, paves the way for fibrotic events that follow.

The targets of immune-mediated damage vary according to the type of GN. For instance, glomerulonephritis associated with staphylococcus shows IgA and C3 complement deposits.[3]

One of the targets is the glomerular basement membrane itself or some antigen trapped within it, as in post-streptococcal disease.[16] Such antigen-antibody reactions can be systemic, with glomerulonephritis occurring as one of the components of the disease process, such as in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or IgA nephropathy.[17] On the other hand, in small vessel vasculitis, cell-mediated immune reactions are the main culprit instead of antigen-antibody reactions. Here, T lymphocytes and macrophages flood the glomeruli with resultant damage.[18]

These initiating events activate common inflammatory pathways, i.e., the complement system and coagulation cascade. The generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and complement products, in turn, results in the proliferation of glomerular cells. Cytokines such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) are also released, ultimately causing glomerulosclerosis. This event is seen in those situations where the antigen is present for longer periods, for example, in hepatitis C viral infection. When the antigen is rapidly cleared, as in post-streptococcal GN, the resolution of inflammation is more likely.[19]

Structural Changes

Structurally, cellular proliferation causes an increase in the cellularity of the glomerular tuft due to the excess of endothelial, mesangial, and epithelial cells.[5] The proliferation may be of two types:

- Endocapillary - within the glomerular capillary tufts

- Extracapillary - in the Bowman space, including the epithelial cells

In extra-capillary proliferation, parietal epithelial cells proliferate to cause the formation of crescents, characteristic of some forms of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis.

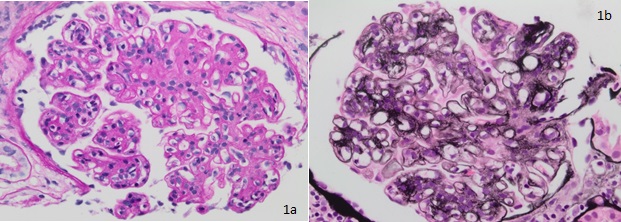

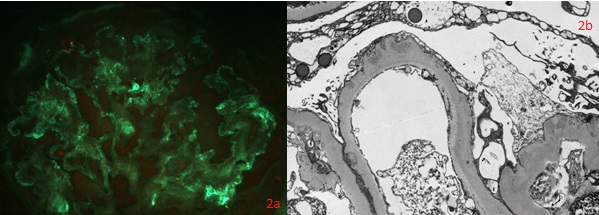

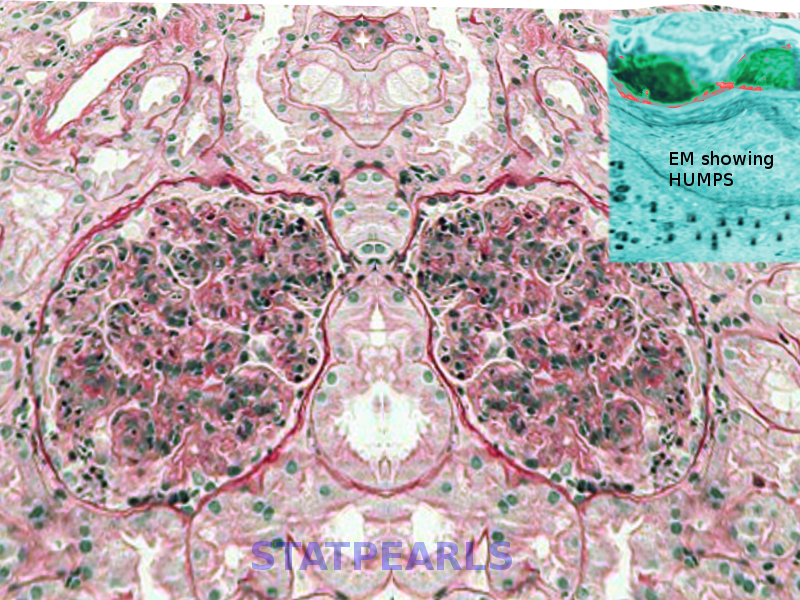

Thickening of glomerular basement membrane appears as thickened capillary walls on light microscopy. However, on electron microscopy, this may look like a consequence of the thickening of the basement membrane proper, for instance, diabetes or electron-dense deposits either on the epithelial or endothelial side of the basement membrane. There can be various types of electron-dense deposits corresponding to an area of immune complex deposition, such as subendothelial, subepithelial, intramembranous, and mesangial. (See the images below)

Features of irreversible injury include hyalinization or sclerosis that can be focal, diffuse, segmental, or global.

Functional Changes

Functional changes include the following:

- Proteinuria

- Hematuria[20]

- Reduction in creatinine clearance, oliguria, or anuria

- Active urine sediments, such as RBCs and RBC casts

This leads to intravascular volume expansion, edema, and systemic hypertension.

Histopathology

Diffuse endocapillary proliferative changes are usually seen in the histopathological analysis of glomerulonephritis. The most common histological patterns observed in the descending order of prevalence are diffuse, focal, and mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis.[21] Of the different histopathological patterns, one of the following may be seen:

- Under light microscopy, a normal glomerular morphology may be seen, while a loss of foot processes on electron microscopy (EM).

- Hypercellular glomeruli result from increased mesangial, endothelial, or parietal epithelial cells; acute and chronic white blood cells may also be seen in diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN), while in crescentic GN, crescents made up of leukocytes and epithelial cells may be present.[22]

- Basement membrane thickening, a feature highlighted by periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain and electron microscopy: EM will demonstrate electron-dense deposits of immune complexes in or adjacent to the basement membrane. The most common pattern of these deposits is sub-epithelial.[23]

- Sclerosis of glomeruli is the end result of glomerular damage from various causes.[24]

History and Physical

It is imperative to obtain a thorough history focusing on identifying some underlying cause of glomerulonephritis, such as systemic disease or recent infection. Mostly, the patient with acute glomerulonephritis is from the pediatric age group, aged 2-14 years, who acutely develops periorbital puffiness and facial swelling in the background of a post-streptococcal infection. The urine is usually dark, frothy, or scanty, and the blood pressure may be high. Nonspecific symptoms include generalized weakness, fever, abdominal discomfort, and malaise.

With acute glomerulonephritis associated with staphylococcal infection, the patient is more likely to be a middle-aged or older male, often diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.[2] The onset may be concurrent with the infection, such as pneumonia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, or a skin infection from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Often, hematuria is present.[25]

History should be taken about the onset and duration of the disease. Symptom onset is often abrupt. In acute postinfectious GN, there is usually a latent period of up to three weeks before clinical presentation. However, the latent period varies; it is typically one to two weeks for the cases that occur after a pharyngeal infection and two to four weeks where post-dermal infection, such as pyoderma, is the cause. Nephritis occurs within one to four days of streptococcal infection usually means preexisting kidney disease.

Identifying a possible etiologic agent is important. Recent fever, sore throat, arthralgias, hepatitis, valve replacement, travel, or intravenous drug use may be associated.[26] Assessing the outcomes of the disease process is also crucial, such as loss of appetite, pruritis, tiredness, nausea, facial swelling, peripheral edema, and dyspnea.

As the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is decreased, symptoms like edema and hypertension occur, majorly due to the subsequent salt and water retention caused by the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

A) Some symptoms occur primarily and include:

- Hypertension

- Edema (peripheral or periorbital) - initially in the dependent areas/areas with low tissue tension

- Abnormal urinary sedimentation

- Hematuria – microscopic or gross[2]

- Oliguria[27]

- Azotemia

- Shortness of breath or dyspnea on exertion

- Headache - secondary to hypertension

- Confusion - secondary to malignant hypertension

- Possible flank pain

B) Or there can be symptoms specifically related to an underlying systemic disease:

- Triad of sinusitis, pulmonary infiltrates, and nephritis – granulomatosis with polyangiitis[28]

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, purpura - Henoch-Schönlein purpura[29]

- Arthralgias - systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Hemoptysis - Goodpasture syndrome or idiopathic progressive glomerulonephritis

- Skin rashes – in hypersensitivity vasculitis, SLE, cryoglobulinemia, Henoch-Schönlein purpura [30]

Patients often have an unremarkable physical examination; however, they may present with a triad of edema, hypertension, and oliguria.

The provider should look for the following signs of excess fluid in the body:

-

Periorbital and/or peripheral edema

-

High blood pressure

-

Fine inspiratory crackles due to pulmonary edema

-

Raised jugular venous pressure

-

Ascites and pleural effusion

Other signs to look for include the following:

-

Vasculitic rash (as with Henoch-Schönlein purpura, or lupus nephritis)

-

Pallor

-

Renal angle fullness or tenderness

-

Abnormal neurologic examination or altered sensorium

-

Arthritis

Evaluation

Following investigations guide not only in determining the potential cause but also in assessing the extent of the damage:

Blood

- Complete blood count - A decreased hematocrit may suggest a dilutional type of anemia. In the background of an infectious cause, pleocytosis may be apparent.

- Serum electrolytes - Potassium levels may be raised in patients with severe renal impairment.

- Renal function tests - BUN and creatinine levels are raised, demonstrating a degree of renal impairment. In addition, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) may be low.

- Liver function tests - May point towards the underlying etiology.

- Immunoglobulins

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Electrophoresis

- Complement (C3, C4 levels) - Differentiation may allow the provider to narrow the differentials. Low complement levels indicate the following diseases: cryoglobulinemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, infective (bacterial) endocarditis, and shunt nephritis. Certain renal disorders may also be considered, such as membranoproliferative GN or post-streptococcal GN. Normal complement levels suggest an underlying abscess, polyarteritis nodosa, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Goodpasture syndrome, idiopathic rapidly progressive GN, immune complex disease, and immunoglobulin G or immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Chauvet et al. reported that in patients with new-onset nephritis and low C3 levels, anti-factor B autoantibodies might help distinguish new-onset post-streptococcal GN from hypocomplementemic C3 glomerulonephritis.[31]

- Autoantibodies, such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and anti-ds-DNA, anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) to rule out collagenopathy as the underlying cause of GN.

- Blood culture - Blood culture is indicated when there is a fever, immunosuppression, intravenous drug abuse, indwelling catheters, or shunts.

- Antistreptolysin O titer (ASOT) increases in 60 to 80% of cases. The rise begins in one to three weeks, peaks in three to five weeks, and returns to baseline in six months. It is unrelated to the severity, duration, and prognosis of renal disease.[32]

- Hepatitis serology - As infectious hepatitis can lead to glomerulonephritis of various types[33]

Urine

The urine is usually dark, and the specific gravity is more than 1.020 with RBCs and RBC casts. The 24-hour urinary protein excretion and creatinine clearance may help establish the degree of renal impairment and proteinuria.[34] The following parameters are usually helpful:

- Microscopy, culture, and sensitivity

- Bence Jones protein

- Albumin to creatinine or protein to creatinine ratio

- RBC casts

Imaging

- Chest X-ray (helps to see for evidence of pulmonary hemorrhage, if any)

- Renal ultrasound (helps in assessing the size and anatomy for biopsy)

Renal Biopsy

The examination of glomerular lesions via a renal biopsy provides the diagnosis of glomerulonephritis by answering the following queries:

- Approximate proportion of involved glomeruli (focal vs. diffuse)

- Approximate involvement of each glomerulus (segmental vs. global)

- Presence of hypercellularity

- Any evident sclerosis

- Any deposits on immunohistology (immunoglobulins, light chains, complement)

- Electron microscopy findings - precise localization of deposits. Exact ultrastructural appearance. Podocyte appearance

- Presence of tubulointerstitial inflammation, atrophy, or fibrosis

- Evident vessel-related pathology[35]

In addition to establishing the etiology, the biopsy also helps determine the severity of the disease and the underlying etiology.[10] It may also reveal other lesions that could be related to the GN.

Treatment / Management

Glomerulonephritis is associated with a systemic disease; it is mostly resolved by managing the underlying cause. Primary glomerulonephritis is managed supportively and by specific disease-modifying therapy. The outcome mainly depends on the timely intervention, which, if not done, may lead to a progressive sequence of events causing glomerulonephritis to develop into chronic kidney disease (increasing the risk for simultaneous development of cardiovascular disease), the sequence finally culminates into end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

The management of glomerulonephritis broadly follows two modalities.

A) Specific management revolves around immunosuppression, which in turn is governed by factors like:

- Histological diagnosis

- Disease severity

- Disease progression

- Comorbidities

The available options include:

- High-dose corticosteroids[36]

- Rituximab (a monoclonal antibody that causes the lysis of B-lymphocytes)[37]

- Cytotoxic agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide, along with glucocorticoids are of value in severe cases of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis)[38]

- Plasma exchange (glomerular proliferative nephritis, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis – used temporarily till chemotherapy takes effect)

B) With progression into chronicity, general management is done on the lines of chronic kidney disease:

- Keeping track of the renal function tests (RFTs), serum albumin, and urine protein excretion rate.

- By controlling the BP and inhibiting the renin-angiotensin axis through Loop diuretics, which serve two purposes; the removal of excess fluid and the correction of hypertension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) are frequently the first choice for managing hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARBs) have been found to halt CKD progression in diabetic or nondiabetic renal disease cases, much like ACEIs.[39]

- For individuals with severe/refractory hypertension with/without encephalopathy, vasodilators (e.g., nitroprusside and nifedipine) can be used.

- Clinicians can manage the complications associated with progressive chronic disease, including anemia, bone mineral disorders, acidosis, cardiovascular disease, and restless legs/cramps.

- Appropriate counseling regarding diet.

- Preparation for renal replacement therapy (RRT), if needed.

Nephritic Glomerulonephritis

IgA nephropathy: ACE inhibitors/ARBs (3 to 6 months) are used as they reduce proteinuria. Corticosteroids and fish oil can be prescribed if proteinuria exceeds 1 gm (provided GFR>50) even after the initial therapy. Henoch Schonlein purpura (HSP) is managed on the same lines. Steroids are also helpful for gastrointestinal tract (GIT) related symptoms here.

Post Streptococcal GN: Supportive treatment and antibiotics to get rid of nephritogenic bacteria.[40]

Anti-GBM Disease: The available options include plasma exchange, corticosteroids, rituximab, and cyclophosphamide.[41]

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN): RPGN is treated with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide.

Plasma exchange is used for anti-GBM/ANCA vasculitis.

For lupus nephritis, monoclonal antibodies, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, corticosteroids, and other immunomodulatory drugs can be used in various combinations.[42][43]

Nephrotic Glomerulonephritis

Minimal change disease: Prednisolone 1 mg/kg (4 to 16 weeks). If relapsing, immunosuppression with greater intensity or for longer durations are options. Cyclophosphamide and calcineurin inhibitors are effective options.[44]

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: Treatment is done initially with ACE inhibitors/ARBs and by controlling BP. Calcineurin inhibitors, plasma exchange, corticosteroids, and rituximab are helpful treatment options.

Membranoproliferative GN: Treatment is done initially with ACE inhibitors/ARBs and by controlling BP. Immunosuppression is useful if no underlying cause is found. Work is currently ongoing to block or modify C3 activation.

Differential Diagnosis

Based on the clinical presentation, differentiation needs to be drawn between the nephrotic and the nephritic spectrum. This is important as it helps to narrow down the differentials of the underlying glomerular pathology. Also, differential diagnoses will include primary versus secondary causes depending on the age group and clinical picture.

Primary glomerulonephritis presenting as the nephrotic syndrome in young patients is likely to be minimal change disease, while in adults, membranous variety is more likely.[45] In the secondary category, diabetes mellitus has to be ruled out.

When nephritic syndrome is the main presentation in children, it is likely post-infectious. In adults, however, IgA nephropathy should be considered. When systemic vasculitis involves glomeruli, the cause in the younger age group is Henoch Schonlein purpura, while in adults, granulomatosis with polyangiitis should be suspected. Lupus nephritis is seen more commonly in young women (20 to 30 years).[46]

Differential Diagnoses

Following are some important differentials to be considered while making the diagnosis of glomerulonephritis:

- Acute kidney injury

- Crescentic glomerulonephritis

- Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis

- Focal segmental glomerulonephritis

- Glomerulonephritis associated with nonstreptococcal infection

- Goodpasture syndrome

- Lupus nephritis

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

The following renal syndromes frequently mimic the early stages of acute GN:

- Idiopathic hematuria

- Chronic GN with an acute exacerbation

- Anaphylactoid purpura with nephritis

- Familial nephritis

Prognosis

Among the Nephritic Spectrum Diseases

- PSGN has an excellent prognosis, especially in children with complete recovery, usually occurring within 6 to 8 weeks. In adults, around 50% of the patients continue to have reduced renal function, hypertension, or persistent proteinuria.[47][48]

- Frequently IgA nephropathy has a benign course.[49] Others gradually progress to ESRD, with ESRD frequency increasing with age.[50] Prognosis is predictable, to some extent, based on the Oxford classification. Additionally, on presentation, nephrotic range proteinuria, hypertension, high serum creatinine level, and widespread intestinal fibrosis of the kidneys indicate a poor prognosis.[51]

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura is typically a self-limited illness that demonstrates an excellent prognosis in patients without renal involvement. The majority of patients fully recover in four weeks.[52] The long-term morbidity of Henoch-Schönlein purpura depends on the extent of renal involvement. Approximately 1% of patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura will develop ESRD and require renal transplantation.[53]

- With timely and avid treatment, pauci-immune GN usually remits (75% of cases). But if left untreated, it carries a very poor prognosis.

- Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis progresses to ESRD inevitably, despite therapy. Also, the frequency of recurrence is high even after a kidney transplant.

Among the Nephrotic Spectrum Diseases

- Minimal change disease has a very good prognosis for all ages if there is a response to corticosteroid therapy. The primary morbidity is related to the adverse effects of the medications.[44]

- Approximately a third of patients with membranous nephropathy who have subnephrotic proteinuria respond to conservative management. Spontaneous remission has also been seen in cases of heavy proteinuria. However, in others with features of nephrotic syndrome, remission may take up to 6 months, provided adequate treatment is given.

- Appropriate treatment does slow the progression of HIV-associated nephropathy, but with progression into ESRD, a kidney transplant may be necessary.

- Amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis takes 2 to 3 years for progression towards ESRD, while for amyloid A (AA) amyloidosis, remission can be achieved by identifying and managing the underlying disease.[2]

Complications

Glomerulonephritis may either lead to acute kidney injury (AKI) or may progress gradually to chronic renal failure. AKI is sometimes the initial presentation in rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with crescent formation. Similarly, vasculitis and Goodpasture syndrome represent other conditions where AKI is associated with glomerulonephritis. Most cases, however, would show progression into chronic glomerulonephritis and eventually lead to CKD and ESRD, requiring dialysis.[54]

The following is a list of complications that providers should be mindful of:

- Pulmonary edema

- Hypertension

- Generalized anasarca

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Hypertensive retinopathy

- Hypertensive encephalopathy

- Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis

- Chronic renal failure

- Nephrotic syndrome

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is important to cut down salts from the diet during acute disease. For progressive disease, dietary restrictions (2 g sodium, 2 g potassium, 40 to 60 g protein; a day) help reduce the build-up of wastes and prevent fluid overload states.

Cessation of smoking is also paramount in decreasing the aggravation of renal disease.[55]

Education in countering diabetes and elevated blood pressure is crucial through adequate lifestyle modifications and standardized therapy. Patients must also be counseled regarding the control of hyperlipidemia.

Problems concerning sexual health (e.g., loss of libido) usually occur in kidney disease, especially in men. Hence, appropriate guidance regarding the same should be provided to the patient.

Patients with nephrotic syndrome, especially those with progression into chronic kidney disease (CKD), are vulnerable to infections, so a seasonal flu vaccine and pneumococcal vaccines help them.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In most instances, the disease follows a progressive course, and the patients often have associated co-morbidities, so the involvement of multiple disciplines and interprofessional communication among healthcare team members is of prime importance. While the nephrologist is almost always involved in treating patients with glomerulonephritis, the role of clinicians cannot be undermined, considering that the patients usually have other diseases simultaneously. Patients presenting in the outpatient departments with proteinuria/hematuria or both would need further evaluation.

A renal biopsy following the initial laboratory and radiological investigations may be needed to reach a diagnosis. This requires a collective approach involving histopathologists, immunologists, radiologists, and at times, surgeons. Nurses are essential in dispensing appropriate treatment and assisting with educating the patient and family. Patients with chronic disease need an assessment of renal function at regular intervals, so linking up with a local community doctor is important. Those with markedly decreased renal function require dialysis with appropriate scheduling, so interacting with the dialysis unit is pivotal. Pharmacists can review patient medications and note those that can tax the renal system, as well as manage medications around dialysis sessions for those patients. All interprofessional team members must follow and monitor the patient, record their observations in the patient's medical record, and communicate with other team members as necessary for potential therapeutic interventions. Prompt consultation with specialists is recommended to improve outcomes, and timely interprofessional communication is imperative to ensure quality health care. [Level 5]