Continuing Education Activity

Meningocele is one of the common congenital neural tube defects. Meningocele is the simplest form of open neural tube defects characterized by cystic dilatation of meninges containing cerebrospinal fluid without any neural tissue. The prognosis of patients with meningocele is excellent with simple surgical repair of the meninges. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of Meningocoele and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of meningocele.

- Review the risk factors for developing neural tube defects.

- Summarize the epidemiology of neural tube defects.

- Outline treatment considerations for patients with meningocele.

Introduction

A simple meningocele comprises of meninges and CSF protruded into the subcutaneous tissue through a spinal defect. Skin overlying meningocele is usually intact. A complex meningocele is associated with other spinal anomalies. Meningocele is a typically asymptomatic spinal anomaly and is not associated with acute neurologic conditions. Neural tube defects are the second most common type of congenital disability after congenital heart defects.

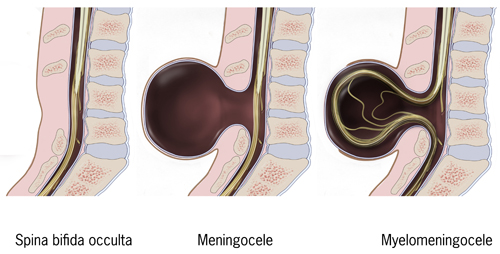

There are two types: open or closed. Spinal dysraphism comprises a spectrum of congenital anomalies stemming in a defective neural arch, from which meninges or neural elements herniate, leading to various clinical manifestations. Spinal dysraphism includes aperta (visible lesion) and occulta (with no visible external lesion). Meningocele, myelomeningocele, lipomeningomyelocele, rachischisis, and myeloschisis are the familiar names based on the pathological findings. Myelomeningocele is the most common among others accounting for 90% of cases.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

The definite etiology of meningocele remains poorly understood. Most isolated neural tube defects appear to be caused by folate deficiency, likely combined with genetic and environmental risk factors. Folate deficiency may be related to inadequate oral intake, use of folate antagonist, or genetic factors causing abnormal folate metabolism. They may also be associated with chromosomal anomalies or single-gene disorders.

Genetic syndromes associated with meningocele include HARD (hydrocephalus, agyria, and retinal dysplasia), Meckel-Gruber syndrome, trisomy 13 or 18. Maternal factors allied with an elevated risk for neural tube defects include advanced and young maternal age, low socioeconomic status, maternal alcohol use during pregnancy, smoking, caffeine use, obesity, high glycemic index, or gestational diabetes. Maternal use of anti-seizure medications like valproic acid and carbamazepine may develop neural tube defects in the fetus. Amniotic bands are also another factor known to disrupt normal neural tube development.

The elevation of maternal core temperature in the first trimester from febrile illness or other sources may be associated with meningocele. The environmental factors like agrochemicals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons can cause neural tube defects.[6][5]

Epidemiology

The incidence of neural tube defects is ranging from 1.0 to 10.0 per 1,000 births worldwide. The prevalence of neural tube defects in the USA and many European countries is around 0.5 to 0.8 per 1000 births, and recurrence risk in subsequent pregnancies is up to 5%. The prevalence of neural tube defects has variable rates among different geography, ethnicity, gender, and countries. Prevalence is higher among Whites as compared to Blacks and females as compared to males. The risk of neural tube defects for some ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Irish and Mexican) is higher than others (e.g., White and Asian).[5][7][8]

Pathophysiology

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are the consequence of a disturbance in the neurulation process. During neurulation, a coordinated series of events gives rise to a neural plate, neural folds, plus the neural tube, which ultimately differentiates and evolves into the future brain and the spinal cord. Neural tube defects arise from the anterior and posterior neuropores as they are last to close. They can be open or closed, based on exposed or closed neural tissue.

Open NTDs are the result of defects in primary neurulation and involve any area of the central nervous system(CNS). Closed NTDs are due to defects in secondary neurulation and present in the spine.

Meningocele results from a failure to develop the caudal end of the neural tube resulting in a protrusion that contains cerebrospinal fluid, meninges, overlying skin, and does not have the spinal cord as its content. Anterior meningocele is usually presacral in location. Intrathoracic meningocele is a fluid-filled sac with the spinal meningeal wall's protrusion into the thoracic cavity through an enlarged intervertebral foramen. Lateral meningocele syndrome (LMS) is a clinical entity with multiple lateral spinal meningoceles (protrusions of arachnoid and dura through spinal foramina), distinctive facial features, hypotonia, joint hyperextensibility, cardiac, skeletal, and urogenital anomalies.

Neurologic manifestations of the meningoceles depend on their size and location, including back pain, neurogenic bladder, paresthesias, and paraparesis. Other neurologic findings can include syringomyelia, Chiari I malformation, and rarely, hydrocephalus. Neural tube defects are complex multifactorial defects involving both environmental and genetic factors.[9][10][4][11][12]

Histopathology

On microscopic examination, meningocele demonstrates a thick fibrous wall, which is lined by flattened arachnoid cells.

History and Physical

The Prenatal screening for neurological defects includes the measurement of maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) and high-quality second-trimester ultrasound to detect fetal anomalies. Meningocele presents as a swelling over the back covered with skin, present at birth. Defects can present at thoracolumbar, lumbosacral, lumbar, thoracic, sacral, and cervical regions. Neurological involvement and deficits are rare in meningocele. On clinical exam, a fluctuant midline mass that transilluminates is present.

The initial assessment of the newborn is essential at birth. A detailed examination of the head and neck, including the head, skull bones, and anterior fontanelle's size and shape, is done. A complete neurological exam shall be done at birth to exclude any neurological abnormalities. The clinical manifestation of the thoracic meningocele is approximatelyrelated to its size and proximity with the surrounding structures. They can present with back pain, shortness of breath, coughing, and palpitations when accompanied by the lung and mediastinal structure compression.[2][9]

Evaluation

All patients must be assessed radiologically after birth, depending on their clinical status. Plain X-rays films show any associated skull defects, bone abnormalities, and deformities of the spine. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best diagnostic test to study the neural tissue abnormalities and assess any associated hydrocephalus. Ultrasonography to have a quick assessment of hydrocephalus can be helpful. Surgery should be on board to evaluate the need for emergent surgical repair.[2]

Treatment / Management

Management is mainly a multidisciplinary approach. It is vital to counsel family regarding the immediate and long-term effects of treatment. Surgery is preferred as soon as it is practical on large meningoceles. In suspected central nervous system infection or meningitis, treatment is started with prophylactic antibiotics and anticonvulsants immediately. Patients require monitoring in the neonatal intensive care unit with an assessment of electrolytes and blood counts. Consider blood grouping and cross-match for possible transfusion.

The association of meningocele with tethered cord syndrome is high. MRI is essential for the diagnosis of meningocele. Active surgical treatment is suggested immediately after definite diagnosis. During surgery, the surgeon should explore the spinal canal and release the tethered cord after repairing the protruded meninges.[2][3]

Differential Diagnosis

Encephalocele attributes to the developmental abnormalities delineated by the herniation of neural tissue through a skull defect. In children with tissue masses in the nasal cavity, presenting with breathing difficulties, menigocephaloceles or meningoceles should be suspected. Clinicians often misdiagnose them as polyps or tumors. Inappropriate treatment of undiagnosed hernias may lead to secondary meningitis or fluid leak due to their incision or puncture.

MRI is a non-invasive, safe imaging method that allows a definite diagnosis of menigocephaloceles and meningoceles. Noonan syndrome shares some similar characteristic facial features as lateral meningocele syndrome. Facial features of lateral meningocele syndrome comprise of arched eyebrows, ptosis, flat midface, thin upper lip, low-set, and posteriorly angulated ears, and low posterior hairline, hands with wide and short distal second and third fingers(pseudo-clubbing).[13][12]

Prognosis

Meningocele usually has no neural involvement and without any acute neurological complications, hence a favorable prognosis. Spina bifida aperta usually presents a skin defect with the looming risk of CSF leak, whereas the occult forms have no visible skin opening. The prevalence of spina bifida at birth has decreased by 23% over ten years between 1995 and 2004 after the Food and Drug Administration mandated fortification of all cereal and grain products with folic acid. In clinical practice, the prognosis of patients with meningocele is excellent, and simple surgical repair is adequate.[5][3][2]

Complications

The compression of meningocele can cause symptoms of increased intracranial pressure due to the displacement of extra spinal cerebrospinal fluid into the intracranial cavity. Raised intracranial tension may cause erosion of the skull base and may result in a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Recent reports indicate that meningocele is often associated with tethered cord syndrome, and those symptoms of tethered cord syndrome occur in a considerable proportion of children who had meningocele repair. Myelomeningocele is commonly associated with hydrocephalus.[1][14][3]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The prevalence of neural tube defects has dipped significantly during the past thirty years due to advances in ultrasonography's refined resolution for in utero fetal examination, the clinical availability of laboratory markers like serum alpha-fetoprotein measurements, termination of affected pregnancies, and consumption of folic acid supplements by women in the reproductive age group.

Mothers with diabetes, obesity, hyperthermia, drugs that interfere with folate metabolisms, excessive vitamin A, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption during pregnancy, and antiepileptic drugs like valproate and carbamazepine have increased risk of children with Neural tube defects. Folic acid supplementation of 4 mg to mothers with risk factors. Prenatal screening for neurological abnormalities is based on an ultrasound performed routinely or oriented by maternal alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) screening around 12, 22, and 32 weeks.[6][2]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A number of institutions have organized spina bifida clinics with a multi-disciplinary care team consiting of neurologists, neurosurgeons, rehabilitation specialists, physical and occupational therapists to take care of children with spinal dysraphism. Such organized treatment is highly recommended to ensure the best care of such patients.