Continuing Education Activity

Thymomas and thymic carcinomas originate from the epithelial cells of the thymus within the anterior mediastinum. The presence of histologic heterogeneity is common among thymomas and as a result benign and malignant thymomas cannot simply be differentiated based on history, however, malignant thymomas are much more invasive compared to their benign counterpart. This activity will focus on the role of the interprofessional team regarding the etiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of thymomas and thymic cancers.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of thymomas and thymic cancers.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of thymomas and thymic cancers.

- Outline the management options available for thymomas and thymic cancer.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the treatment of thymomas and thymic cancers and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Thymomas and thymic carcinomas originate from the epithelial cells of the thymus within the anterior mediastinum. The thymus is an encapsulated bilobed gland. Each lobe of the thymus has a superior and inferior horn and extends laterally to each respective phrenic nerve. The thymus is supplied by branches off of the internal mammary, inferior thyroid, and pericardiophrenic arteries. It is drained by tributaries from the innominate vein or directly into the superior vena cava (SVC). The thymus is vital in the development of the adaptive immune system and commonly involutes after puberty into fibrofatty tissue. There has been a strong association between myasthenia gravis and thymomas that was found incidentally in 1939 by Alfred Blalock. The presence of histologic heterogeneity is common among thymomas, and as a result, benign and malignant thymomas cannot simply be differentiated based on history; however, malignant thymomas are much more invasive compared to their benign counterpart.[1] The 15-year survival rate is 12.5% in patients with invasive thymomas and 47% in patients with noninvasive thymomas. Deaths related to thymomas usually occur from cardiac tamponade or other cardiorespiratory complications.

Etiology

There are no known risk factors for the development of thymomas or thymic carcinoma. The etiology of thymic neoplasms remains unknown. There is a strong association of thymomas with myasthenia gravis and other paraneoplastic syndromes such as total red cell aplasia, polymyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Cushing syndrome, and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.[2][3][4][5] Thirty to forty percent of patients with a thymoma experience symptoms suggestive of myasthenia gravis. An additional 5% of patients have paraneoplastic syndromes.

Epidemiology

Thymomas and thymic carcinomas are the most common mass of the anterior mediastinum.[6] They account for approximately 20% of all mediastinal neoplasms. They commonly occur between the fourth and sixth decades of life. No sexual or racial predilection exists.

Pathophysiology

A thymoma is a malignant epithelial tumor most commonly found in the prevascular mediastinum. It also can be found in the neck, pulmonary hilum, thyroid, lung, pleura, or pericardium. In gross examination; it is a well-circumscribed, tan, firm mass that ranges in size from microscopic to over 30 cm in diameter. It is lobulated with bands of fibrous stroma and, at times, cystic changes.

Thymic carcinomas lack a lobulated architecture in contrast to thymomas. They possess the cytoarchitectural features of carcinoma and lack immature T cell lymphocytes. Thymic carcinomas and thymomas can be synchronous. Thymomas at times can develop into carcinomas; however, they often take 10 to 14 years to do so. Grossly they are large, firm, infiltrating masses with numerous areas of cystic change and necrosis. Fifteen percent or less are encapsulated.

Histopathology

The World Health Organization Classification system is described below:

- Type A

- Composed of bland spindle cells and few scattered lymphocytes

- 60% of these are in stage I

- They tend to have good patient outcomes.

- There is an atypical variant that is hypercellular, possesses increased mitotic activity, and/or is necrotic. The presence of necrosis tends to predict an advanced stage.

- Type AB

- This is a mixture of type A and types B1 or B2.

- It is composed of intermixed or distinct components.

- 67% of these are in stage I.

- Type B1

- Composed of predominantly lymphocytes with scattered epithelial cells, not in clusters

- Also paler medullary islands with rare Hassall corpuscle-like structures

- 50% of these are in stage I

- Type B2

- Composed of mostly epithelial cells forming clusters and medullary islands may be present

- Atypia may be more present and may show anaplastic features

- 32% of these are in stage I

- Type B3

- Composed predominantly of large, polygonal cells with increased atypia and few scattered lymphocytes

- Its prognosis is worse than other thymomas but is better than thymic carcinomas.

- Only 19% of these are in stage I.

Histologic heterogeneity is common among thymomas meaning many thymomas will possess multiple subtypes of these WHO classifications and can be divided into ten percent increments. Thymomas have a lobulated architecture. The cellular lobules consist of neoplastic epithelial cells and reactive thymocytes that are intersected with fibrous bands. They are at least partially surrounded by fibrous capsules.

Thymoma subtypes A and AB have some characteristic growth patterns. They possess microcystic changes, storiform growth, staghorn-shaped vessels, rosettes, gland-like structures, or papillary growth patterns. They often show prominent plasma cell infiltrates and myoid cells (rhabdomyomatous thymoma).

A dilated perivascular space is seen in thymoma subtypes B1, B2, and B3. These are filled by plasma fluid and may contain a few lymphocytes, plasma cells, or foamy macrophages. In the center of these spaces, there are often small vessels with hyalinized walls. Neoplastic cells surround these spaces in palisades. Hassal corpuscles are specifically seen in subtype B1 thymomas.

Both subtype B1 and B2 thymomas are lymphocyte rich; however, they possess some important histologic differences. Subtype B1 has areas of medullary differentiation (medullary islands) and scattered epithelial cells without clustering (< 3 contiguous epithelial cells). These are often mistaken for small lymphocytic lymphomas and can be differentiated by using a keratin stain. Subtype B2 has more epithelial cells that cluster (3+ contiguous epithelial cells). Subtype B3 is often confused with thymic carcinoma or metastatic SCC from other sites.

Immunohistochemistry is helpful in identifying thymomas. Thymic epithelial cells are positive for keratins, epithelial membrane antigens, p63, p40, and PAX8. Thymic lymphocytes stain with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), CD1a, CD3, CD45, and CD99. Subsets of thymoma subtype A and AB stain for CD20 and rarely thyroid transcription factor (TTF-1).

Thymomas have an unusually low mutation burden. The most common mutations in thymic tumors include:

- General transcription factor I (39% to 42%)

- p53(25% to 36%)

- KIT(6-20%)

- Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (11% - also found in thymic carcinoma and B3 thymoma)

- A rare occurrence - n-ras, k-ras, cyclin D1, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated, ERBB4, FGFR3, SMARCB1, and STK11 genes

Histologically thymic carcinomas have a distorted architecture with various sized cell nests and even single cells in desmoplastic stromal reactions. There are often cytologic malignant and cystic changes along with certain amounts of necrosis, atypia, and mitoses. T cells found in thymic carcinomas exhibit the phenotype of mature T cells (TdT negative, CD1a negative, CD3 positive, CD4, or 8 positives). B cells and plasma cells are also seen.

There are a variety of histologic subtypes of thymic carcinoma, emphasizing the ability of the thymic epithelium to differentiate. They are summarized below:

- Squamous cell carcinoma - keratinizing or nonkeratinizing

- Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma

- Composed of malignant, large, polygonal cells

- Grow in a syncytial pattern in sheets and nests

- There is usually a dense lymphoid infiltrate

- Possesses the morphology of nasopharyngeal lymphoepithelial carcinoma

- Epstein Barr virus (EBV) may play a role in its pathogenesis

- It is highly aggressive with a poor prognosis

- Sarcomatoid carcinoma

- Possesses sarcoma-like areas

- Possesses possible heterologous components (rhabdomyoblastic or cartilaginous differentiation)

- Confirm diagnosis by identification of t(X;18) (p11.2;q11.2), SYT-SSX1, or SYT-SSX2 gene fusion

- Clear cell carcinoma

- Possesses a lobulated growth pattern

- Composed of uniform clear cells with minimal nuclear atypia, glycogen, and no mucin

- Very rare

- Has a poor prognosis due to local recurrence or metastases

- Basaloid carcinoma

- Possesses nests of polygonal and spindle cells with peripheral palisades, a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, and absence of keratinization often with cystic changes

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

- Composed of intermediate cells (which are polygonal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, small round nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli), squamous cells, and mucin-producing cells

- Defined as low or high grade

- Presence of a mastermind-like transcriptional coactivator 2 (MAML2) rearrangement is disease defining

- Adenocarcinoma

- Subtype based on histologic features (papillary, adenoid cystic carcinoma like, mucinous, and not otherwise specified)

- Occasionally has an intestinal phenotype

- Undifferentiated carcinoma

- Consists of sheets of undifferentiated cells

- Epithelial nature confirmed by immunohistochemistry

- NUT (nuclear protein of testis) carcinoma

- Rare cancer

- Very aggressive

- 51% have metastases at the time of presentation.

- The median survival is 6.7 months and is invariably fatal.

- The median age of presentation between 16 and 50 years of age

- No gender predilection

- It is a subset of squamous cell carcinoma.

- Immunostain shows a speckled nuclear expression pattern.

- 70% have a rearrangement of the NUT gene.

- A SMARCA4-deficient tumor (SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily A, member 4)

- Possess sarcomatous or carcinomatous features

- Has focal rhabdoid morphology

- Loss of BRG1 expression is diagnostic

- 83% of these tumors possess cytokeratin expression

- The median age of diagnosis is 59 years of age

- 2-year survival is worse with BRG1-retained tumors (12.5% versus 64.4%)

History and Physical

Patients with thymomas or thymic carcinomas present in one of three ways:

- An incidental finding on imaging in an asymptomatic patient

- A patient symptomatic due to the local compressive effects of the mass within the thoracic cavity (e.g., dyspnea, cough)

- A patient symptomatic due to a paraneoplastic syndrome

There are various manifestations with which a patient with thymoma may present. Patients may have thoracic manifestations. These symptoms are related to the size and effect of the thymoma on adjacent organs, including chest pain, cough, and phrenic nerve palsy. Some patients with thymomas may present with superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome. Pleural and pericardial effusions in patients with a thymoma tend to be due to disseminated disease.

Patients with thymomas may have paraneoplastic manifestations as well. The most common paraneoplastic syndrome seen is myasthenia gravis. These paraneoplastic symptoms can occur at any time in the diagnosis and treatment process of thymomas. Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder that results in an immunologic attack of acetylcholine receptors at the neuromuscular junction of skeletal muscle. These patients tend to present with diplopia, ptosis, dysphagia, weakness, or fatigue. Approximately half of the patients with thymoma have myasthenia gravis and usually have less advanced disease since their symptoms lead to an earlier diagnosis. A thymectomy leads to the attenuation of the severe symptoms of myasthenia gravis.

Another autoimmune disorder associated with thymomas is pure red cell aplasia. This is a non-proliferation of erythrocyte precursors in the bone marrow. It occurs in 5% to 15% of patients with thymomas and is more common in older women. It is often seen in thymomas with a spindle cell pathology. Various immunodeficiency syndromes can also be seen in association with thymomas. Less than 5% of patients with thymomas have hypogammaglobulinemia or pure white cell aplasia. These syndromes are more common in older women (similar to pure red cell aplasia). Approximately 10% of patients with acquired hypogammaglobulinemia have a thymoma (also known as Good syndrome). This is usually a thymoma with spindle cell pathology. Symptoms of these immunodeficiency syndromes include recurrent infections, diarrhea, and lymphadenopathy. However, thymectomy does not resolve the immunodeficiency (unlike myasthenia gravis). Finally, there is a syndrome known as thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity (TAMA). This is similar to graft versus host disease (GVHD). These patients present with a morbilliform skin rash, chronic diarrhea, and liver enzyme abnormalities. A biopsy will show similar histopathology as GVHD in skin or bowel mucosa.

Thymic carcinoma presents differently. It is more aggressive compared to a thymoma and usually is associated with invasion of other mediastinal structures. Patients present with cough, chest pain, phrenic nerve palsy, or SVC syndrome. Extrathoracic metastases are seen in less than 7% of patients with thymic carcinoma and include kidney, extrathoracic lymph nodes, liver, brain, adrenal glands, thyroid, and bone.

Evaluation

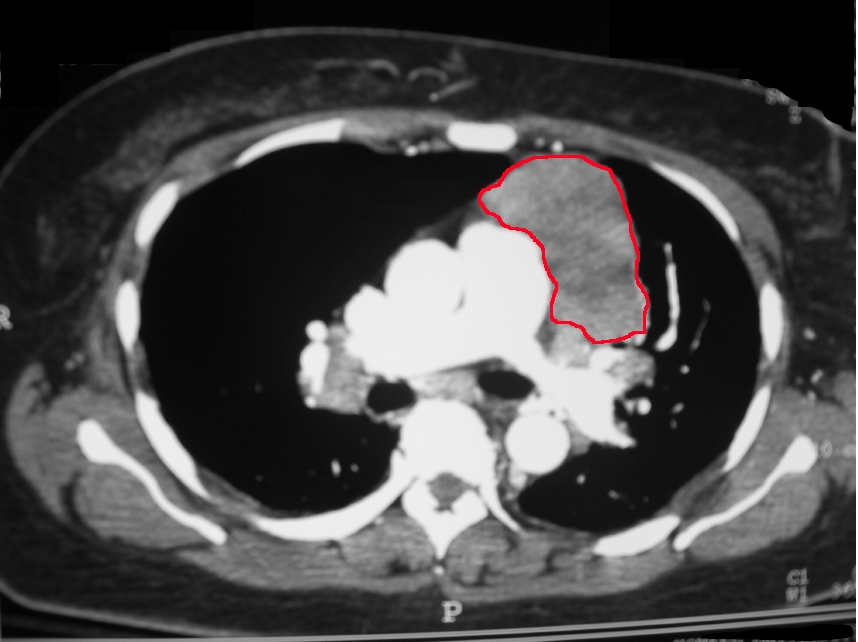

The diagnosis of thymoma or a thymic carcinoma starts with a CT or MRI of the chest. This is to evaluate if the mass is resectable. Thymic carcinomas tend to have areas of necrosis, cystic changes, or calcifications. In contrast, thymomas tend to be smooth and well-circumscribed. CT of the chest can evaluate the mass and its association with other mediastinal structures. MRI can differentiate between solid and cystic masses. PET scans are also of use in the differentiation of benign thymomas and thymic carcinomas. Well-differentiated thymomas tend to be PET negative, whereas thymic carcinomas tend to be PET-positive.

In addition to imaging, the patient should have various laboratory studies drawn including germ cell markers (beta-hCG and AFP) and lymphoma markers (LDH and CBC) since both germ cell tumors and lymphomas are in the differential of anterior mediastinal masses. Pulmonary function tests and a cardiac stress test should also be performed on any patient in whom surgical resection is being considered to determine if they have enough cardiopulmonary reserve to withstand a significant resection of the thymus.

A definitive diagnosis of a thymic tumor needs tissue.[7] This can be obtained either via surgical resection (in the case of small encapsulated tumors and resectable larger tumors), or be obtained via a percutaneous or open biopsy in instances in which the tumor is unresectable, the tumor requires neoadjuvant therapy, or surgery is contraindicated due to age or comorbidity. The percutaneous route is done using CT guidance and can be a fine needle aspiration or a core needle biopsy. An open biopsy can be performed thoracoscopically, via a cervical mediastinoscopy, via an anterior mediastinotomy (Chamberlain procedure), or at times via endobronchial ultrasound. Correct pathological identification and staging are critical in determining what the proper manner of treatment should be.

Treatment / Management

Treatment and management of thymic tumors include chemoradiotherapy, the use of corticosteroids, immunotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and surgical resection. The utilization of multidisciplinary tumor boards is vital in determining the correct method of treatment of these neoplasms. There has been no randomized controlled trial that provides definitive guidance for management strategies.[8][9][10]

In the setting of resectable disease, i.e., an encapsulated tumor or a tumor invading resectable structures (the pericardium, the pleura, or an area of the lung), surgery is indicated since an R0 resection is feasible. Typical management includes total thymectomy and a lymph node dissection. The likelihood of long-term survival depends on the completeness of the resection. Of note, there is often an inflammatory fibrous reaction that mimics invasion and should be noted and marked by the surgeon on the specimen for the pathologist. In patients with myasthenia gravis who are to undergo resection, they need to complete a careful preoperative evaluation and have their disease controlled medically before resection. Anesthesia needs to be consulted and have a cautious plan in terms of induction, intubation, and extubation.

Some patients have potentially resectable disease, which is a tumor that is invading the nominate vein, phrenic nerve(s), or the heart and great vessels. These patients need multimodal therapy that includes preoperative chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy. These patients should be re-evaluated after neoadjuvant treatment to determine if their disease is resectable; in which case, surgery is recommended. Surgical approaches can be aggressive and include pleurectomy or an extrapleural pneumonectomy, followed by postoperative radiotherapy (PORT). If their disease is deemed not resectable, the patient should undergo tumor debulking and PORT. In cases of thymic carcinoma and postoperative residual disease, patients should receive adjuvant chemotherapy with radiotherapy.

Patients with the unresectable disease are those with extensive pleural and pericardial metastases, un-reconstructable great vessel, heart or tracheal involvement, or distant metastases. Such patients should receive systemic therapy (either radiotherapy alone or chemoradiotherapy). Patients who are medically unfit for surgery due to age or extensive comorbidities should also be considered for this. Their therapies should be individualized based on their extent of disease, their symptoms, and their performance status. Chemoradiotherapy has been shown to improve long-term survival and symptoms in some patients. Radiotherapy alone palliates thoracic symptoms such as dyspnea and cough using a total dose of 60 or more Gy. Chemotherapy is used as the primary palliative therapy for widespread disease.

Finally, in cases of recurrent disease, surgical resection is recommended in cases of localized recurrence (drop metastases) and has been shown to lead to prolonged survival. In other cases of more extensive recurrence, chemotherapy or palliative radiotherapy is recommended.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for thymomas and thymic carcinomas include thymic carcinoid tumors (that are often seen in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 1), thymic cysts (that can be differentiated from solid tumors by MRI of the chest), non-Hodgkins lymphomas, germ cell tumors (especially in young males with prior testicular masses), ectopic parathyroid glands (that can be identified by a sestamibi scan), thyroid goiters, and rarely paragangliomas.

In order to narrow down the differential, one must order appropriate laboratory studies [including germ cell markers (AFP and hCG) and lymphoma markers (LDH and CBC with differential)]. Imaging studies can help to differentiate between these various masses, e.g., an MRI differentiates between a cystic and solid mass, a sestamibi scan can detect ectopic parathyroid tissue, and a thyroid scan can detect a mediastinal thyroid goiter.

Surgical Oncology

Prior to surgical resection, the resectability and tumor stage must be confirmed by either biopsy or diagnostic thoracoscopy. Pulmonary fuction tests (PFTs) and cardiac screening prior to surgery are helpful to see if the patient will tolerate surgery. Also, in cases of patients with myasthenia gravis, additional preoperative measures must be undertaken. No patient in myasthenic crisis should be considered for surgical resection. Patients should receive plasmapheresis prior to surgery, and their steroid dose should be minimized. These patients often may need stress dosing before thymectomy.

There are three surgical approaches one can adopt: Median sternotomy, transverse neck incision, or thoracoscopic surgery (robotic surgery). The boundaries of a radical thymectomy are clearly defined: Laterally, the phrenic nerves, inferiorly the diaphragm, and superiorly the thyrothymic ligament. The superior horn extends high into the neck and deep to the sternohyoid muscle. The resection of the mediastinal pleura, pericardium, adjacent lung, innominate vein, or unilateral phrenic nerve is sometimes required for an R0 resection (which is the most critical long-term prognostic indicator). Both R1 and R2 resections have been correlated with local recurrence.

Lymph node dissection is an integral part of the surgery. Anterior thymic (or N1) nodes include the space around thymus, anterior to pericardium and great vessels, below hyoid, above the diaphragm, between mediastinal pleura, and posterior to the sternum. Deep thymic (or N2) nodes include the lower jugular, supraclavicular, internal mammary, upper paratracheal, lower paratracheal, subaortic/aortopulmonary window, and hilar nodes. It is recommended that both levels are removed in cases of thymic carcinoma and thymomas with the invasion of mediastinal structures. In cases of thymomas without mediastinal invasion, only N1 level nodes should be excised.

There are several postoperative complications associated with thymectomy. These are summarized below:

- Respiratory failure and prolonged intubation - commonly seen in patients with myasthenia gravis

- Pleural effusion, pneumonia, atelectasis, pneumothorax, and acute lung injury

- Phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

- Phrenic nerve injury

- This can be avoided by limiting dissection, traction, and the use of electrocautery around the nerve.

- If the nerve is injured, one can see if the palsy resolves over time. If it does not, diaphragmatic plication or phrenic nerve reconstruction are options in skilled hands.

- Left recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

- This leads to vocal cord paralysis

- Commonly occurs in aortopulmonary window dissection

- Right recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

- Occurs around the right subclavian artery which is above the innominate vein and outside margin of thymectomy

- Surgical site infection and mediastinitis - Reduce risk by reducing steroid use (especially in patients with myasthenia gravis)

Radiation Oncology

The indications for postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) in patients with thymomas vary. In stage I (Masaoka stage I-II) thymomas with no capsular invasion, no PORT is recommended since no survival benefit is shown. Annual thoracic imaging is all that is needed. In stage I (Masaoka stage I-II) thymomas with invasion into the mediastinal fat or pleura, PORT is recommended if there are high-risk features present (larger tumor size, microscopic, or grossly positive margins). PORT has been shown to reduce recurrence risk to that seen with an R0 resection and in tumors with lower-risk features. In stage II-III (Masaoka stage III) thymomas, PORT is indicated due to the higher recurrence risk. Finally, in stage IV (Masaoka stage IV) thymomas, individualized radiotherapy is recommended in addition to palliative therapy and curative therapy for oligometastases.

As was the case for thymomas, thymic carcinomas also have varied indications for PORT. In stage I to III (Masaoka stage I to III) thymic carcinomas, there is a higher risk of local recurrence and a survival advantage seen with PORT. If there is a positive margin or residual disease after resection, supplemental adjuvant chemotherapy is also recommended. In stage IV (Masaoka stage IV) thymic carcinoma, PORT is recommended for palliation of local symptoms.

Typically, the dosage recommended for PORT is 45 to 50 Gy divided into 1.8 to 2 Gy fractions over five weeks directed to the tumor bed and the adjacent mediastinum. This dosage is increased to 60 Gy divided into 2 Gy daily fractions for those with residual disease.

As with most oncologic therapies, there are associated toxicities. These include esophagitis, pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, pericarditis, and rarely myelitis. All of which are treated symptomatically. Some late sequelae include the risk of lung fibrosis and a small chance of constrictive pericarditis. Patients also are at increased risk of accelerated coronary atherosclerosis and secondary malignancies.

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

There have been multiple retrospective reviews and analyses that are used in the construction of the indications for PORT. The Japanese Association for Research on Thymus (JART) conducted the most extensive series. These analyses found PORT was associated with improved relapse-free survival but no improved overall survival in patients with thymic carcinoma. They also found no relapse-free survival or overall survival in thymoma patients from postoperative radiotherapy. In contrast, other retrospective reviews have found a survival benefit with postoperative radiotherapy for thymomas, e.g., the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group and National Cancer Center Database analyses.

A SEER database analysis showed superior overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with thymomas who received postoperative radiotherapy. A subgroup analysis of these patients suggested this benefit was limited to stage III and IV disease.

Medical Oncology

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy is utilized for those with potential resectable, unresectable, and recurrent disease. This is generally chemotherapy. However, immunotherapy and vascular epidermal growth factor (VEGF) tyrosine kinase inhibitors are utilized in thymic carcinomas that have been refractory to initial chemotherapeutic regimens. These include:

- Pembrolizumab is a checkpoint inhibitor that is used to treat thymic carcinoma refractory to initial chemotherapeutic regimens in patients with no history of autoimmune disorders.

- This indication is based on nonrandomized phase II data.

- Possible adverse effects include myocarditis, myasthenia gravis, and hepatitis.

- It is not offered to thymoma patients because they have shown a higher rate of adverse effects.

- Nivolumab has no role in the treatment of relapsed thymic carcinoma. The PRIMER trial has shown significant toxicity with this drug with no benefit.

- Sunitinib, which is a VEGF inhibitor that inhibits multiple tyrosine kinases included VEGF and c-kit, is utilized on thymic carcinomas that have progressed on both chemotherapy and immunotherapy.

- VEGF inhibitors are also used in more advanced thymomas and patients with a history of autoimmune disorders

- Sunitinib is given in 6-week cycles (4 weeks on and two weeks off)

- Its benefits were tested utilizing a phase II open-label single-arm trial.

- Its toxicities include lymphocytopenia, fatigue, mucositis, and decrease ventricular ejection fraction.

- Lenvatinib is used for thymic carcinoma refractory to initial chemotherapeutic regimens.

- Its benefits were examined in the REMORA trial that showed a 38% partial response and a 57% stable disease rate.

- Its adverse effects include hypertension, diarrhea, hand-foot syndrome, proteinuria, hypothyroidism, and thrombocytopenia.

There are quite a few initial chemotherapeutic regimens. They are described below:

- CAP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) given every three weeks.

- Studied in a U.S. intergroup trial

- Overall and complete response rate - 50 and 10%

- Median survival - 38 months

- PE (cisplatin and etoposide) is given every three weeks.

- EORTC (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer) study

- Overall and complete response rate - 56% and 31%

- Median progression-free and overall survival - 2.2 and 4.3 years

- CAP with prednisone given every three weeks.

- Complete response rate - 77%

- Carboplatin and paclitaxel were given every three weeks.

- Studied in a prospective multicenter study in patients with advanced disease

- Overall response rate - 43% (thymoma) and 22% (thymic carcinoma)

- ADOC (cisplatin, doxorubicin, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide) given every three weeks.

- Studied in patients with advanced disease

- Overall and complete response rate - 92% and 43%

- Median survival - 15 months

- VIP (etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin) given every three weeks.

- Studied in Intergroup trial - patients with advanced thymoma or thymic carcinoma.

- Only partial responses observed.

Often initial chemotherapy is insufficient, and the progression of the disease is seen. Therefore subsequent chemotherapeutic agents are needed. These include etoposide, ifosfamide, pemetrexed, octreotide, 5-FU and leucovorin, gemcitabine with or without capecitabine, and paclitaxel.

Staging

Several different systems are used for the staging of thymomas, including the AJCC TNM system and the Masaoka system. These two systems are summarized below.

AJCC TNM System

T Classification

- T1: encapsulated or extending into mediastinal fat

- T1a: No mediastinal pleural invasion

- T1b: Mediastinal pleural invasion

- T2: Partial or full-thickness pericardial invasion

- T3: Invasion of the lung, brachiocephalic vein, SVC, phrenic nerve, chest wall, or extra-pericardial pulmonary artery or veins

- T4: Invasion of the aorta (ascending, arch, or descending), arch vessels, intra-pericardial pulmonary artery, myocardium, trachea, or esophagus

N and M Classification

- N0: no nodal metastases

- N1: peri-thymic nodal metastases

- N2: deep thoracic nodal metastases

- M0: no distant metastases

- M1a: Individual pleural or pericardial nodule(s)

- M1b: Pulmonary nodule or distant organ metastases

Staging

- Stage I - T1a/b N0 M0

- Stage II - T2 N0 M0

- Stage IIIA - T3 N0 M0

- Stage IIIB - T4 N0 M0

- Stage IVA - Any T N1 M0

- Stage IVA - Any T N0, 1 M1a

- Stage IVB - Any T N2 M0, 1a

- Stage IVB - Any T Any N M1b

Masaoka Clinical Stage

- Stage I Completely encapsulated tumor

- Stage II Microscopic invasion of the capsule

- Stage III Macroscopic invasion into surrounding structures

- Stage IVA Pleural or pericardial metastases/nodules

- Stage IVB Lymphogenous or hematogenous (distant) metastases

Prognosis

Thymomas are slow-growing neoplasms. The most accurate adverse prognostic marker is the invasiveness of the tumor. On the other hand, thymic carcinomas are more aggressive and have a poorer prognosis compared with thymoma. Prognosis is dependent on the stage of the disease and the complete resectability of the tumor.

A German series studied the prognosis of various stages of thymic tumors. Their findings are summarized below:

- The prognosis was found to be excellent for Masaoka stage I and II thymomas.

- The prognosis was worse following resection in Masaoka stage III thymomas.

- There was a 27% recurrence rate and an 83% 10-year survival in Masaoka stage III thymomas.

- Masaoka stage IV thymomas have a 10-year survival rate of 47%.

- There was no tumor-related death seen in type A, AB, or B1 disease (Masaoka stage I and II)

- There was a rate of tumor-related death of 9, 19, and 17% in B2, B3, or thymic carcinoma and a rate of death of 50% to 60% in Masaoka stage III and IV thymomas.

After treatment, annual imaging is recommended even though no clinical trials have shown benefit to such imaging. It is recommended that a CT chest is ordered every six months for two years and annually for five years in cases of thymic carcinoma and ten years in cases of thymomas.

Thymic tumors tend to recur as pleural nodules, most commonly with a mean length of 8 to 68 months after treatment.

Thymic tumors carry a risk of development of a second malignancy (approximately 17% to 28% risk after thymectomy). According to the SEER database, there is an increased risk for B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, gastrointestinal cancers, and soft tissue sarcomas.

Complications

Complications include radiation pericarditis, radiation pneumonitis, and pulmonary fibrosis. These tend to occur after postoperative radiotherapy and can lead to patient death. Therefore, clinicians must carefully consider a risk-benefit analysis before recommending adjuvant radiotherapy.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for patients with stage III or IV thymomas, even those with complete resection.

Consultations

Patients with thymomas and thymic carcinomas will require a medical and radiation oncology services consultation. A neurology consult should be made both pre- and postoperatively in patients with myasthenia gravis. Anesthesiology should be consulted before any planned thymectomy in patients with myasthenia gravis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients with myasthenia gravis should have a screening CT scan of the chest looking for thymomas or thymic hyperplasia. Thymectomy has been shown to lead to symptom improvement in these patients.

Pearls and Other Issues

- An MRI of the chest can differentiate between thymoma and a thymic cyst.

- The most common syndrome associated with thymomas is myasthenia gravis.

- The most accurate method of determining if a patient with myasthenia gravis can tolerate a thymectomy from a respiratory status is a negative inspiratory force (NIF). If it is -20 or less, this patient is the right candidate for surgical resection.

- Patients with myasthenia gravis should receive intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis before scheduled thymectomy. They should also be weaned off any immunosuppressants and have their corticosteroid dosages reduced to have the least amount of negative effect on wound healing.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Primary care physicians and thoracic surgeons are more likely to encounter thymomas. Thymomas are also found incidentally on imaging by emergency department physicians. The treatment of thymomas should be undertaken by a multidisciplinary team at all times to determine appropriate treatment strategies. A thoracic surgeon should be involved with all cases of anterior mediastinal masses and thymomas; however, the consultation of other specialists may be needed, including medical and radiation oncologists, as well as a neurologist in patients with known myasthenia gravis. Often these neoplasms present asymptomatically and are found incidentally. Symptoms are related to local effects from the mass or paraneoplastic syndromes. Further imaging and lab studies are utilized to narrow down the differential.