Continuing Education Activity

Foreign body aspiration remains a significant cause of death in children for anatomic as well as developmental reasons. Choking is typically defined as an aerodigestive foreign body causing varying amounts of obstruction to the airway. The obstruction can lead to difficulties with ventilation and oxygenation thus resulting in significant morbidity or mortality. Items that are most commonly implicated in children include food, coins, toys, and balloons. The main cause of death has been attributed to hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and less commonly, pulmonary hemorrhage. This activity reviews the evaluation of a patient suspected of having aspirated a foreign body and the role of the interprofessional team in caring for this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the frequency of morbidity and mortality associated with foreign body aspiration.

- Explain the airway difficulties expected with foreign body aspiration.

- Review the most common foreign bodies aspirated.

- Outline the evaluation of a patient suspected of having aspirated a foreign body and the role of the interprofessional team in caring for this life-threatening condition.

Introduction

Foreign body aspiration remains a significant cause of death in children for anatomic as well as developmental reasons. Choking is typically defined as an aerodigestive foreign body causing varying amounts of obstruction to the airway. The obstruction can lead to difficulties with ventilation and oxygenation thus resulting in significant morbidity or mortality. Items that are most commonly implicated in children include food, coins, toys, and balloons. The main cause of death has been attributed to hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and less commonly, pulmonary hemorrhage. [1][2]

Etiology

Items that are most commonly implicated in accidental foreign body ingestion, particularly in children, include food, coins, toys, and balloons.

Epidemiology

According to the National Safety Council, in 2016 the rate of fatal choking in American children <5 years of age in the general population was 0.43 per 100,000. However, a previous study analyzing non-fatal choking data of children under the age of 14 has revealed a comparatively higher rate of 20.4 per 100,000 population. 55.2% of these non-fatal choking cases in children <4 years of age involved candy, with hot dogs and nuts being more likely to require hospitalization. Males accounted for 55.4% of cases but there was no statistically significant difference between the sexes. Analysis of the national trend of inorganic foreign body aspiration has revealed that aspirated coins have decreased in relative frequency with aspirated jewelry conversely becoming more common in the United States. Overall the rate of aspiration from foreign bodies resulting in emergency department visits has remained stable between the years of 2001 and 2014.

A recent meta-analysis of the worldwide literature on foreign body aspiration revealed a sex discrepancy with 60% of patients being males. Nuts were seen to be causative in 40% of cases in high-income and low-middle income nations. Among inorganic foreign bodies, a pooled proportion among the literature stemming from high-income countries revealed that magnets were causative in 34% of the cases. Diagnosis was delayed by more than 24 hours in 60% of those particular cases. [3][4][5]

Pathophysiology

Young children are particularly at risk for foreign body aspiration. One study has shown the mean age to be 24 months with 98% of cases involving children < 5 of age. As airway resistance is inversely related to the cross sectional radius by a power of four, the relatively smaller diameter of pediatric airways means that they are more prone to significant airflow obstruction with even small foreign bodies. Dental development also contributes to the risk of foreign body aspiration, as molars typically are not present before the age of 2; thus children in this age group are able to bite pieces of food with their incisors but not effectively able to grind food into smaller pieces. Additionally, young children tend to explore the world with their mouths while playing and exhibit high levels of activity and distractibility while eating, further putting them at risk. Due to the relative anatomical narrowing of the tracheobronchial tree in children, the proximal airway is typically the site of obstruction. In fact, in one retrospective review, 96% of foreign bodies aspirated were found in this location. In children <15 years of age, foreign bodies lodge within the left lung almost as often as in the right lung. This is due to the symmetric tracheal take-off angle found between the two bronchi in many children prior to the development of a prominent aortic indent affecting the trachea and left main bronchus. Regardless of age, if there is noticeable aortic indentation on the trachea when examining radiographs, then the right bronchial angle will be less distinct compared to the left side and aspiration will be more common in the right lung [1][3][6][7][8]

History and Physical

Patients may be completely asymptomatic and the only evidence of an aspiration event may be found during history taking. However, sudden onset of cough, choking, and/or dyspnea have been found to be the most common symptoms. One prospective study has cited a sensitivity of 91.1% and specificity of 45.2% for choking and acute cough. Wheeze on auscultation has been found to be a major physical finding and in one study was documented in 60% of cases. In the same study, 32% of patients had asymmetric breath sounds. An abnormal physical exam has been seen to have a sensitivity of 80.4% and specificity of 59.5% for foreign body aspiration. [5][6][7]

Evaluation

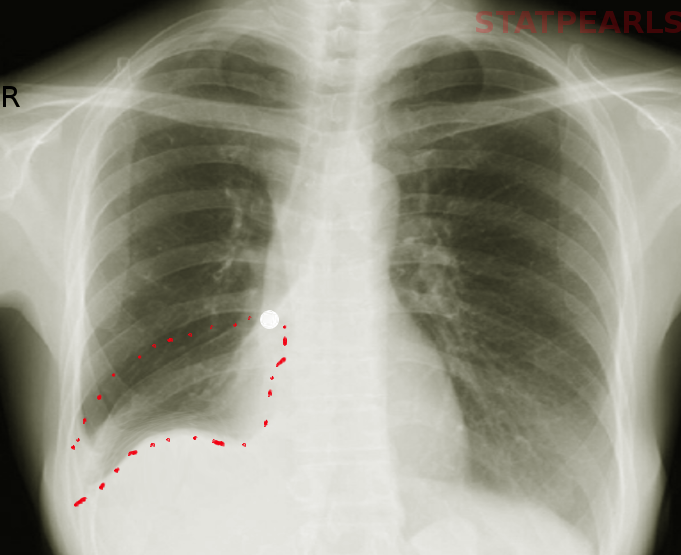

Chest radiographs are often utilized as initial tool of investigation for foreign body aspiration. Radiological findings consistent with a foreign body aspiration include atelectasis, pneumothorax, and air trapping. However, chest radiographs have been seen in multiple studies to be frequently normal, with one study citing a normal chest radiograph in 35% of cases of foreign body aspiration. This same study indicated that the most common abnormality found on radiograph was air trapping, present in 53% of cases. The sensitivity of chest radiograph has been documented as 67.9% and the specificity has been seen to be 71.4%. In one study, children with a concerning history of sudden cough, abnormal pulmonary exam, and abnormal chest x-ray have been shown to have a risk of 88.6% (P<0.001) for foreign body aspiration. It is important to note that rarely a single finding or historical piece of information can definitively diagnose a foreign body aspiration. Rather, direct identification via bronchoscope is often needed.

In a review of common imaging modalities for diagnosis of foreign body aspiration, a simple algorithm based on feasibility and utility was generated at one institution. Recommendations included initial diagnostic work-up with frontal and lateral chest films with additional neck films if warranted on exam. Abnormalities at this stage would be sufficient to necessitate bronchoscopy. However, if the radiographs are unrevealing in the symptomatic patient with a suggestive history, a CT of the chest should subsequently be performed. If CT is unavailable and the child is > 5 years of age, then inspiratory-expiratory films can be obtained. If the child is younger than 5 years old, bilateral decubitus films are preferred. Fluoroscopy and MRI can be used as adjunctive measures. It should be noted that this was an algorithm formulated at one particular institution and is not universal practice.

To mitigate the potential need for CT scan, one study has evaluated a quantitative method to increase the sensitivity of radiographs to detect foreign bodies, in particular aspirated objects which are radiolucent. In a case-control study, radiodensity ratios were compared between the affected lung and the contralateral lung in patients with definitively diagnosed foreign body aspiration and healthy controls. The radiodensity ratio was seen to be significantly higher in in patients with aspiration as compared to controls. Radiodensity was calculated for each lung by measuring total Hounsfield units and then the ratio developed involved comparison between the affected lung and the normal lung. The authors of this study suggest a radiodensity ratio cutoff of 1.10 is sufficiently positive to warrant further investigation with bronchoscopy, whereas a ratio below this value would warrant further work-up with a CT scan. As there is a relative paucity evaluating this method in the literature, further studies are needed for validation.[5][6][7][9][10]

Treatment / Management

The definitive diagnosis and management of a foreign body typically involves bronchoscopy to remove the offending object. However, no universal standard of care has been thoroughly defined. Rigid bronchoscopy has been described to have several key benefits compared to flexible bronchoscopy for definitive management. Some cited reasons include: 1) the ability to ventilate via the rigid bronchoscope, 2) improved visualization with a rigid telescope, and 3) greater versatility to accommodate various sizes of suctioning and optical forceps. Additionally, the rigid scope offers a wider space to manipulate the offending object and to facilitate removal while avoiding obstruction at the level of the glottis. In cases of diagnostic uncertainty or complexity such as in recurrent pneumonia with no clear history of an aspiration, a flexible bronchoscopy may be the preferred initial test.

According to one study, when a combination of three or more highly suggestive clinical and radiological diagnostic data were noted, the risk of identifying a foreign body in the airway was 91%. Diagnostic clinical criteria significantly correlated with the presence of a foreign body included: a history of sudden choking, cyanosis, apnea, and decreased breath sounds. Diagnostic radiological criteria included: atelectasis, mediastinal shift, or signs of air trapping. The absence of the aforementioned criteria was very predictive of a negative flexible bronchoscopy. Thus, it was deemed safe to refer these patients for outpatient follow-up as opposed to initial bronchoscopy. [6][11][12]

Differential Diagnosis

Often times, foreign bodies in the upper trachea can be mistaken for viral croup as an acute aspiration may cause symptoms of stridor. Additionally, a foreign body that is lodged in the esophagus of a younger child may cause stridor simply secondary to mass effect on the trachea. A lingering foreign body may present as a nidus for recurrent pneumonia in the long-term setting. Asthma and viral upper respiratory tract infections can obscure the diagnosis. In one study, 34% of patients who underwent flexible bronchoscopy but were found not to have a foreign body had persistent abnormal chest radiographs. In these selected patients, the most common finding on chest radiographs was bronchial thickening. Symptoms of concurrent respiratory infection were present in 42.5% of these patients. [11][13]

Prognosis

A large retrospective review identified the mortality rate among pediatric patients with foreign body aspiration to be 2.5%. Age was seen to be correlated with the anatomic location of the foreign body with increasing age positively correlated to increasing distal anatomic location of the aspiration. Unsurprisingly, neurologic disability was the most common condition among patients with aspiration. This particular co-morbidity was associated with increased odds of death (OR 3.11) and mechanical ventilation (OR 2.56). A lodged foreign body lower in the respiratory tract carried a comparatively higher odds of mortality compared to those proximally positioned. It is believed by the authors that this is secondary to significant mucous plugging along with later dislodgement resulting in contralateral obstruction and hypoxia. Despite this, foreign bodies present in the trachea had the highest odds of requiring mechanical ventilation. [12]

Complications

A myriad of complications including recurrent pneumonia, bronchiectasis, lung abscess, and atelectasis can occur from a missed foreign body aspiration. Bronchial stenosis is also a well-known complication of chronic foreign bodies in the airway. However, nearly universal, tracheal lacerations are the most commonly reported complication among affluent countries. Pneumonia is the most common complication among countries with a poorer socioeconomic status. In a retrospective study evaluating risk factors associated with a missed diagnosis of foreign body aspiration, the incidence of a major complication was often seen to be increased the longer a foreign body was present in the airways. Obstructive emphysema was found to be the most common complication for foreign bodies discovered >3 days after the initial event. Importantly, it should be noted that a normal radiograph with absent physical findings does not exclude the possibility of an aspirated foreign body. Furthermore, patients on bronchodilators and steroid may suppress reactive respiratory symptoms. [5][13]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Since the invention, spread, and refinement of bronchoscopy by pioneers such as Gustav Killian and Chevalier Jackson, the rate of mortality and morbidity of foreign body aspiration has remarkably decreased. In addition, preventative measures, such as the recommendations put forth by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2010, have been enacted in an attempt to reduce the overall incidence of foreign body aspiration. One of the measures proposed included further collaboration between the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) along with the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) to provide a surveillance system and set of regulations for food items. At that time, the CPSC already had legislation and surveillance in place for choking hazards stemming from toys. However, food regulation was comparatively lacking. The AAP offered broad recommendations in their policy statement including routine food warning labeling and increased public education of new food hazards as they enter the consumer market. [1][14]